Open FINAL DISSERTATION Etd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sponsored by Congratulates and Honors W

sponsored by Congratulates and Honors W Donna G. Klein & Col. Dell M. Dempsey as Women of the Year 601 Poydras Street, 12th Floor | New Orleans, LA 70130 | (504) 586-1200 | FAX (504) 596-2800 www.mcglinchey.com Published by NOPG LLC 111 Veterans Memorial Blvd., Suite 1440, Metairie, LA 70005 504-834-9292; Fax: 504-837-2258. 2008 of the Publisher: D. Mark Singletary Associate Publisher: Lisa Blossman Managing Editor: Greg LaRose Anniversary News Editor: Christian Moises Y Autumn C. Giusti, Renee Aragon-Dolese Y Associate Editors: Art Director: Alex Borges Account Executives: Liz Baldini, Jeanne Farrell, Cassie Foreman, Ginger Graf, Coco Evans Judd contents Production Manager: Julie Bernard Photographer: Frank Aymami Introduction . .5 Jacquelyn Clarkson . .31 Nancy Marshall . .54 Past honorees . .6 Michelle Craig . .32 Anne Milling . .55 WCarol Solomon . .8 Bernie Cullen . .33 Cheryl Mintz . .56 Jacqueline Alexander . .10 Elizabeth Dannewald . .35 Beverly Nichols . .57 Heather Alleman . .11 Nancy Scott Degan . .37 Michelle Nugent . .58 Sandra Andrieu . .12 Dell Dempsey . .38 Beth Payton . .59 Therese Badon . .13 Johnette Downing . .39 Tara Richard . .60 Jesyka Bartlett . .14 Patti Ellish . .41 Jade Russell . .61 Lauren Baum . .15 Cathi Fontenot . .43 Elizabeth Scheer . .62 Penny Baumer . .16 Elizabeth Futrell . .44 Rachael Schorr . .63 Dottie Belletto . .19 Jocelyn Greely . .45 Stacy Seamon . .64 C. Lynn Besch . .20 Samantha Griffin . .46 Pamela Senatore . .65 Julia Bland . .25 Jayne Gurtler . .47 Kristin Shannon . .66 Kim Boyle . .26 Kristine Hatfield . .48 Jessica Soileau . .67 Cindy Brennan . .27 Laura Held . .49 Charlee Williamson . .68 Christine Briede . .28 Donna Klein . .50 Rachel Wisdom . .69 Debbie Brockley . .29 Priscilla Lawrence . -

Harrah's New Orleans Casino & Hotel

Harrah’sHarrah’s NewNew OrleansOrleans CasinoCasino && HotelHotel 8 8 PMOLinkPMOLink sponsored by “When I tell people about Peoples Health…” “I say to them, ‘Let me tell you what they’ve done for me.’” – Peggy Yeager, Peoples Health Member It started out as routine check-up for 71-year-old Peggy Yeager. “I like everything about Peoples Health,” she says. “I think that She had no idea she was sick. But her doctor wasn’t comfortable y’all were smart enough from the beginning to hire all good people, at all with something he found. He sent her for additional tests because everything – every answer you are looking for – is always and found that Peggy had an abdominal aortic aneurism – taken care of.” a condition blamed for some 15,000 deaths in the U.S. every year. She needed surgery. Peggy Yeager is 73 now. She’s been a member of Choices 65 – a Medicare health plan from Peoples Health – since she turned 65. Peggy was hospitalized for 10 days. “I was in ICU for seven days and “If you want to do the best thing that you’ve ever done in your life, then three days after that in a regular single room… It didn’t cost us please believe me: become a Peoples Health member,” Yeager says. a penny,” she said. “We know that with Medicare alone, we would “Without a doubt it really saved my life.” have had to come up with a good bit of money. We were fortunate enough to have learned about Peoples Health.” Peoples Health is the administrator for Tenet Choices, Inc. -

The Attack on the Tulane Law Clinic

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 4 Access to Justice: The Social Responsibility of Lawyers 2000 Denying Access to Legal Representation: The Attack on the Tulane Law Clinic Robert R. Kuehn Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Robert R. Kuehn, Denying Access to Legal Representation: The Attack on the Tulane Law Clinic, 4 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 033 (2000), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol4/iss1/5 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Denying Access to Legal Representation: The Attack on the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic Robert R. Kuehn* I. THE SHINTECH PROPOSAL AND AN APPEAL FOR FREE LEGAL ASSISTANCE.........................................................................38 A. “Enough is Enough”........................................................38 B. The Tulane Environmental Law Clinic Provides Legal Assistance.......................................................................47 II. A BACKLASH AGAINST ACCESS TO ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE .....51 A. Governor Foster’s Hostility Toward and Threats Against Tulane ............................................................................51 -

Culinary-2009

2 Culinary Connoisseurs Culinary Connoisseurs Inside: Introduction . .5 Best New Restaurants Best Sous Chefs Past honorees . .6 Hostel New Orleans . .16 Emanuel Jones . .31 Culinary Connoisseurs Latil’s Landing . .16 Brandon Muetzel . .31 event photos . .20 Restaurant Amis . .17 Alfred Singleton . .32 Restaurant Rambla . .18 Heather Young . .32 Best Fine Dining Establishments Best Caterers Best Sommeliers Arnaud’s . .7 Joel Catering . .19 Joe Briand . .33 Emeril’s Delmonico . .8 LaBella’s Catering . .19 BY FRANK AYMAMI COVER PHOTO Muriel’s Jackson Square . .8 Best Pastry Chefs Ralph’s on the Park . .9 Best Owners Simone Fleming . .33 Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse . .9 John Besh and Tariq Hanna . .34 Octavio Mantilla . .25 Andre McKendall . .34 Best Casual Upscale Dining Dickie Brennan . .25 Laurent Moecklin . .35 Published by the NOPG LLC Establishments Ralph Brennan . .26 Marguerite Riehm . .35 111 Veterans Memorial Blvd., Café Giovanni . .10 Emeril Lagasse . .26 Suite 1440, Metairie, La. 70005 Clancy’s . .10 Duke LoCicero . .27 (504)834-9292; Fax: (504)837-2258 Cochon . .11 Best Maitre D’s Dick and Jenny’s . .11 Best Executive Chefs Michael Juan . .36 Publisher and president: D. Mark Singletary Herbsaint . .12 Scott Boswell . .27 Associate Publisher: Lisa Blossman Justin Devillier . .28 Legend Managing Editor: Greg LaRose Best Neighborhood Dining Tenney Flynn . .28 Ella Brennan . .36 News Editor: Christian Moises Establishments Brian Landry . .29 Associate editor: Autumn C. Giusti Bear’s Po-Boys . .13 Gus Martin . .29 Lifetime Achievement Art director: Alex Borges La Petite Grocery . .13 Jacques Saleun . .30 Sterling Constant . .37 Account executives: Liz Baldini, Jeanne Farrell, Mandina’s . .14 David Slater . -

Masterfile Main Edition Magazines and Journals

MasterFILE Main Edition Magazines and Journals 1401 = Total number of journals & magazines indexed and abstracted (325 are peer-reviewed ) 1294 = Total number of journals & magazines in full text (280 are peer-reviewed ) *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Full Text Peer- PDF Image Country Availability* MID Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Delay Review Images QuickVie (Months) ed (full w page) Trade Publication 1539- ABA Bank Marketing American Bankers Association 07/01/2001 12/31/2013 07/01/2001 12/31/2013 Y United States of Available Now 92HV 7890 America Trade Publication 2333- ABA Bank Marketing & Sales American Bankers Association 01/01/2014 10/31/2015 01/01/2014 10/31/2015 Y United States of Available Now H9RM 0295 America Trade Publication 0147- Across the Board Conference Board Inc. -

Playing the Big Easy: a History of New Orleans in Film and Television

PLAYING THE BIG EASY: A HISTORY OF NEW ORLEANS IN FILM AND TELEVISION Robert Gordon Joseph A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Cynthia Baron, Advisor Marlise Lonn Graduate Faculty Representative Clayton Rosati Andrew Schocket © 2018 Robert Joseph All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Cynthia Baron, Advisor Existing cultural studies scholarship on New Orleans explores the city’s exceptional popular identity, often focusing on the origins of that exceptionality in literature and the city’s twentieth century tourism campaigns. This perceived exceptionality, though originating from literary sources, was perpetuated and popularized in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries by film and television representations. As Hollywood’s production standards evolved throughout the twentieth century, New Orleans’ representation evolved with it. In each filmmaking era, representations of New Orleans reflected not only the production realities of that era, but also the political and cultural debates surrounding the city. In the past two decades, as the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and the passage of film tax credits by the Louisiana Legislature increased New Orleans’ profile, these debates have been more present and driven by New Orleans’ filmed representations. Using the theoretical framework of Guy Debord’s spectacle and the methodology of New Film History and close “to the background” textual analysis, this study undertakes an historical overview of New Orleans’ representation in film and television. This history starts in the era of Classical Hollywood (1928-1947) and continues through Transitional Hollywood (1948-1966), New Hollywood (1967-1975), and the current Age of the Blockbuster (1975-). -

June 25, 2011 for Immediate Release Contact: C. James Dowden, Alliance Executive Director 310/364-0193

June 25, 2011 For Immediate Release Contact: C. James Dowden, Alliance Executive Director 310/364-0193 THE ALLIANCE ANNOUNCES 2011 EDITORIAL EXCELLENCE AWARD WINNERS FOR LEADING BUSINESS PUBLICATIONS LOS ANGELES—The Alliance of Area Business Publications presented 108 awards to newspaper and magazine business periodicals June 25, 2011, the climax of its three-day annual Summer Conference in Providence, RI. There were 487 entries from 45 publications in the competition this year. Despite the economy, entries remained close to last year. Divisions include Magazines, Newspapers, Open, Online and Best of Show. Gold, silver and bronze awards were presented in most categories. “A couple of the judges noted that there were more upbeat or good news business stories this year. The business press sees the trends more quickly than the general media, so that would portend a good economic future,” noted contest coordinator Prof. Daryl Moen of the University of Missouri School of Journalism. “The web and digital newsletter divisions continue to get better. Best body of work for a single reporter in the newspaper category attracted the most entries and was highly competitive.” The annual Editorial Excellence Awards competition recognizes excellence in journalism, photography and design achieved by regional business publications. Judges (profiled in attached list) are comprised of faculty members from the University of Missouri School of Journalism, with qualifications in respective areas. "The purpose of the Alliance competition is to encourage a high level of journalistic performance and service to communities by recognizing editorial excellence and outstanding visual presentation in regional business publications," said Alliance Executive Director C. -

The Impact of Blogs on State Politics

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 The mpI act of Blogs on State Politics Emily Metzgar Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Metzgar, Emily, "The mpI act of Blogs on State Politics" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1398. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1398 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF BLOGS ON STATE POLITICS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Emily Metzgar B.A., University of Michigan – Ann Arbor, MI, 1993 M.A., The George Washington University - Washington, DC, 1997 August 2008 © Copyright 2008 Emily Therese Metzgar All rights reserved ii To my parents. Thank you. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people contributed to the successful completion of this project and while space does not permit me to list all of them, several individuals deserve special mention. First, thank you to the chair of my committee, Dr. Kirby Goidel, who smilingly processed my ideas while simultaneously offering more realistic options. I have appreciated his support, his humor and his willingness to give me enough rope to get into trouble. -

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY Good Business Should Be More Than Just a Balance Sheet

2018-2019 MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY Good business should be more than just a balance sheet. Giving back means making a real and positive difference in people’s lives today and tomorrow. Entergy New Orleans has a long history of investing in our communities through employee volunteer programs, community grants and economic development leadership that helps encourage and fund new business and job opportunities. Entergy supports its employees and the community, and takes responsibility for helping to make the world a better place. Learn more about our community and economic development activities at entergyneworleans.com. OZANAM INN KINGSLEY HOUSE STEM NOLA DELGADO COMMUNITY COLLEGE A message from Entergy New Orleans, LLC ©2018 Entergy Services, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 13872 Entergy ENO Chamber 8.125x10.875.indd 1 5/10/18 10:43 AM Your Dream. Our Mission. “Something in me said, ‘I have to do this. This is my dream.’ Hancock Whitney helped my business dream become a reality.” Casey K., Founder of Blended Designs At Hancock Whitney, we help people achieve their dreams by providing financial solutions with expertise and warm 5-star service. We are committed to creating opportunities for people and supporting our communities. Learn how our mission can help you build your dreams. Watch the full story and others at Hancock Whitney Bank, Member FDIC. hancockwhitney.com/insights Table of 2018-2019 MEMBERSHIP Contents DIRECTORY New Orleans Chamber of Commerce 1515 Poydras St., Suite 1010, New Orleans, Louisiana 70112 Welcome to the Chamber ............................................................4 Phone: (504) 799-4260 Fax: (504) 799-4259 Board of Directors ................................................................... 6-7 [email protected] www.neworleanschamber.org Chairman’s Council ................................................................ -

S P O N S O R E D

WOY.2004.covers 10/15/04 2:04 PM Page 1 sponsored by WOY.2004.covers 10/15/04 2:04 PM Page 2 &+() /RXLVLDQD¶V ³RXUFKRLFH´ 'JSTU/VSTF.BHOFU)PTQJUBM (DVW-HɱHUVRQ*HQHUDO+RVSLWDODQG WKH(-*+)RXQGDWLRQFRQJUDWXODWH RXU:RPDQRIWKH<HDU-DQLFH.LVKQHU 510%$&+(&KLHI2SHUDWLQJ 2ɷFHUDQG1XUVH([HFXWLYH -DQLFHKDVEHHQDGHGLFDWHGQXUVH OHDGHUDQGSDWLHQWDGYRFDWHIRUWKHSDVW \HDUV+HUKDUGZRUNDQGGHYRWLRQ KHOSHG(-*+EHFRPH/RXLVLDQD¶V¿UVW 1XUVH0DJQHW+RVSLWDODWHVWDPHQWWR WKHRXWVWDQGLQJHQYLURQPHQWRIFDUH VKHKHOSHGWRFUHDWH :H OOEHKHUH &BTU+FGGFSTPO(FOFSBM)PTQJUBM ZZZHMJKRUJ WOY 2004 10/15/04 5:55 PM Page 1 IT IS ROCKET SCIENCE Information Technology is electrons and silicon, data, perform IT contracting and outsourcing, create copper and fiber – and it is rarely perfect when the networks, implement enterprise storage and security switch is turned on. Investments vaporize as critical systems, and provide a full range of off-the-shelf failures materialize. We are the “rocket scientists” who software and hardware tools. We seek to become make it work – Diamond Data Systems. We deliver tailored your consultant and partner – not just sell IT. Our goal IT solutions that impact the bottom line performance of is to enhance the productivity of your firm, reduce our clients in business, government, and scientific risk, and contribute to your bottom line. And because communities. We engineer custom software, integrate we know rocket science, you don’t have to. CONSULTING CUSTOM SOFTWARE CONTRACTING OUTSOURCING DATA INTEGRATION NETWORKS STORAGE SECURITY SOFTWARE SALES HARDWARE 5732 SALMEN STREET SUITE C NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA 70123 504.729.9100 800.218.9009 [email protected] WOY 2004 10/15/04 6:12 PM Page 2 2004 CityBusiness Women of the Year Congratulates Virginia "Gini" Davis, P.T., M.A. -

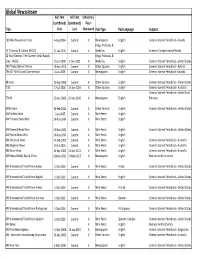

April 2019 Proquest Title List.Xlsx

Global Newsstream Full Text Full Text Scholarly / (combined) (combined) Peer‐ Title First Last Reviewed Pub Type Pub Language Subjects 100 Mile House Free Press 4‐Aug‐2004 Current N Newspapers English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Canada Blogs, Podcasts, & 13.7 Cosmos & Culture [BLOG] 21‐Jan‐2016 Current N Websites English Sciences: Comprehensive Works 24‐Hour Dorman [The Gazette, Cedar Rapids, Blogs, Podcasts, & Iowa ‐ BLOG] 21‐Jul‐2009 1‐Dec‐2011 N Websites English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States 24X7 News Bahrain Online 19‐Dec‐2010 Current N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Bahrain The 40 ‐ Mile County Commentator 6‐Jan‐2009 Current N Newspapers English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Canada 48 hours 15‐Aug‐2009 Current N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States 7.30 17‐Jul‐2003 11‐Apr‐2019 N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Australia General Interest Periodicals‐‐United Arab 7DAYS 25‐Dec‐2006 22‐Dec‐2016 N Newspapers English Emirates @This Hour 10‐Feb‐2014 Current N Other Sources English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States AAP Bulletin Wire 1‐Jan‐2005 Current N Wire Feeds English AAP Finance News Wire 24‐Nov‐2004 Current N Wire Feeds English AAP General News Wire 24‐Nov‐2004 Current N Wire Feeds English General Interest Periodicals‐‐United States AAP Sports News Wire 24‐Nov‐2004 Current N Wire Feeds English ABC Premium News 24‐Feb‐2003 Current N Wire Feeds English General Interest Periodicals‐‐Australia ABC Regional News 10‐Jul‐2003 Current N Wire Feeds -

Document Title

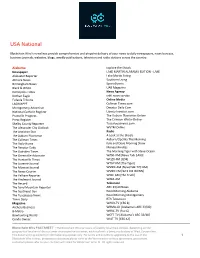

USA National Blockchain Wire’s newslines provide comprehensive and pinpoint delivery of your news to daily newspapers, news bureaus, business journals, websites, blogs, weekly publications, television and radio stations across the country. Alabama Explore the Shoals Newspaper LAKE MARTIN ALABAMA EDITION - LAKE Alabaster Reporter Lake Martin Living Atmore News Southern Living Birmingham News SportsEvents Black & White UAB Magazine Demopolis Times News Agency Dothan Eagle cnhi news service Eufaula Tribune Online Media LAGNIAPPE Cullman Times.com Montgomery Advertiser Decatur Daily.Com National Catholic Register Liberty Investor.com Prattville Progress The Auburn Plainsman Online Press-Register The Crimson White-Online Shelby County Reporter Tuscaloosanews.com The Alexander City Outlook WVTM Online The Anniston Star Radio The Auburn Plainsman A Look at the Shoals The Cullman Times Auburn/Opelika This Morning The Daily Home Kyle and Dave Morning Show The Decatur Daily Money Minutes The Gadsden Times The Morning Tiger with Steve Ocean The Greenville Advocate WANI-AM [News Talk 1400] The Huntsville Times WQZX-FM [Q94] The Luverne Journal WTGZ-FM [The Tiger] The Monroe Journal WVNN-AM [NewsTalk 770 AM] The News-Courier WVNN-FM [92.5 FM WVNN] The Pelham Reporter WXJC-AM [The Truth] The Piedmont Journal WZZA-AM The Record Television The Sand Mountain Reporter ABC 33/40 News The Southeast Sun Good Morning Alabama The Tuscaloosa News Good Morning Montgomery Times Daily RTA Television Magazine WAKA-TV [CBS 8] Archery Business WBMA-LD [Alabama's ABC 33/40] B-Metro WBRC-TV [Fox 6] Bowhunting World WCFT-TV [Alabama's ABC 33/40] Condo Owner WIAT-TV [CBS 42] Blockchain Wire FACTSHEET | The Blockchain Wire service is offered by local West entities, depending on the geographical location of the customer or prospective customer, each such entity being a subsidiary of West Corporation.