(Viable) Lessons from Ed Newman By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September (1973)

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Formation of the National News Council Judicial Ethics and the National News Council 8-1973 The aN tional News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September The aN tional News Council, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/nnc Recommended Citation The aN tional News Council, Inc., The National News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September (1973). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/nnc/168 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Judicial Ethics and the National News Council at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Formation of the National News Council by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 197J 19 By lORN I. O'CONNOR TelevisIon NE of the more significant con are received. The letter concluded that tuted "a controversial Issue ext public In three ·centralized conduits? If the frontations currently taking place "in our view there is no~hing contro importance," networks do distort, however uninten Oin the television arena involves versial or debatable in the proposition Getting no response from the net tionally, who will force them to clarify? the case of Accuracy in Media, that nat aU pensions meet the expecta work that it considered acceptable, AIM In any journalism, given the pressure Inc., a nonprofit, self-appointed "watch tions' of employes or serve all persons took its case to the FCC, and last of deadlines, mistakes are inevitable. -

NBC, "The Nation's Future"

THE NATION'S FUTURE Sunday, October 15, 1961 NBC Television (5 :00-6 :00 PM) "THE ADMINISTRATION'S DOMESTIC RECORD: SUCCESS OR FAILURE?" MODERATOR: EDWIN NEWMAN GUESTS : THE HON. ABRAHAM RIBICOFF SENATOR EVERETT M. DIRKSEN ANNOUNCER: The Nation's Future, October 15, 1961. This is the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, Abraham A. Ribicoff. Secretary Ribicoff believes that the Kennedy Administration's Domestic Record represents a success on the "New Frontier". 'This is Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen, Republican of Illinois and Senate minority leader. Senator Dirksen believes that the Administration's Domestic Record represents a failure on the "New Frontier". The Administration's Domestic Record: Success or Failure? Our speakers, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, Abraham A. Ribicoff, and Senator Everett McKinely Dirksen, Republican of Illinois. ANNOUNCER: In our audience, government officials, political t CONT 'D) figures, journalists, the general public. Now, here is our moderator, the noted news corres- pondent, Edw in Newman. Good evening. Welcome to the primary debate in the new season of NE he Nation ls Future". In the coming months we wiu'be bringing to you again the foremost spokesmen of our time in major debates on topics of nati6nal and international importance. Again it will be my pleasure to act as moderator for the series. Tonight, a debate on the Kennedy Administrat ion Is Domestic Record. This is an appropriate time for such a debate. Congress adjourned late last month and its achieve- ments or failures are being vigorously argued. Criticism of the Administration record has intensi- fied and Administration spokesmen have come to the defense of that record. -

Debate Between the President and Former Vice President Walter F

Debate Between the President and Former Vice President Walter F. Mondale in Kansas City, Missouri October 21, 1984 Ms. Ridings. Good evening from the Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City. I am Dorothy Ridings, the president of the League of Women Voters, the sponsor of this final Presidential debate of the 1984 campaign between Republican Ronald Reagan and Democrat Walter Mondale. Our panelists for tonight's debate on defense and foreign policy issues are Georgie Anne Geyer, syndicated columnist for Universal Press Syndicate; Marvin Kalb, chief diplomatic correspondent for NBC News; Morton Kondracke, executive editor of the New Republic magazine; and Henry Trewhitt, diplomatic correspondent for the Baltimore Sun. Edwin Newman, formerly of NBC News and now a syndicated columnist for King Features, is our moderator. Ed. Mr. Newman. Dorothy Ridings, thank you. A brief word about our procedure tonight. The first question will go to Mr. Mondale. He'll have 2\1/2\ minutes to reply. Then the panel member who put the question will ask a followup. The answer to that will be limited to 1 minute. After that, the same question will be put to President Reagan. Again, there will be a followup. And then each man will have 1 minute for rebuttal. The second question will go to President Reagan first. After that, the alternating will continue. At the end there will be 4-minute summations, with President Reagan going last. We have asked the questioners to be brief. Let's begin. Ms. Geyer, your question to Mr. Mondale. Central America Ms. Geyer. Mr. Mondale, two related questions on the crucial issue of Central America. -

Speaking Freely. PUB DATE 15 Sep 74 NOTE 40P.; Interview of Albert Shanker by Edwin Newman on VNBC-TV (New York City, Channel 4, September 15, 1974)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 103 526 UD 014 893 AUTHOR Shanker, Albert TITLE speaking Freely. PUB DATE 15 Sep 74 NOTE 40p.; Interview of Albert Shanker by Edwin Newman on VNBC-TV (New York City, Channel 4, September 15, 1974) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Activism; Community Control; Educational Finance; *Educational Needs; Educational Planning; Educational Policy; Educational Problems; Ethnic Groups; Governance; *Politics; *Public Policy; School Community Relationship; *Teacher Associations; *Teacher Militancy ABSTRACT In this interview, Albert Shanker, president of the United Federation of Teachers of New York City, executive vice president of the American Federation of Teachers, and vice president of the AFL/CIO, discussed such topics as the following: his participation in a meeting of labor leaders with President Ford on September 11; the potential influence of teachers if they were organized; the intention of the government to handle the current crisis by maintaining a hard money policy; the deterioration in the quality of education over the last four or five years; the sort of social progress which could be brought about by teacher action; the limitations of collective bargaining as an instrument; the prospect that a teachers' union or unions will be able to do what held like them to do without a merger between the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association (NEA); attacks on public education; the dissatisfaction with the public schools among, not only middle class people, but among working class people who feel that the schools don't do for their children what they ought to do; community control; the prospect of a merger for your own purposes and teachers' own protection between the A.F.T. -

Wnbc Television

From The Collected Works of Milton Friedman, compiled and edited by Robert Leeson and Charles G. Palm. Interview. Interviewed by Edwin Newman. Speaking Freely (WNBC), 4 May 1969. MR. NEWMAN: Speaking Freely today is Milton Friedman. Milton Friedman is a professor of economics at the University of Chicago, he is one of the best known and influential economists in the world. He’s an advocate of what might be called the free market approach to the country’s problems. Professor Friedman is celebrated as a critic and opponent of government intervention. He was a principal advisor to Barry Goldwater during the Presidential campaign in 1964. Mr. Friedman, for a number of reasons, one of them of course your association with Senator Goldwater but more specifically the 13 or so books you’ve written and your whole career as an economist, you are generally described as a conservative. But you like to call yourself a liberal. Now, most people who call themselves liberal probably would push you out of the door, so why do you choose that label? MR. FRIEDMAN: The liberal, if you look it up in the dictionary, has to do with freedom—liberalism is the doctrines of and pertaining to freedom. And the basic component of my belief is the belief that we should adopt arrangements which will give each individual separately as much freedom as possible so long as he doesn’t interfere with the freedom of others. Traditionally and historically, this is the meaning the term liberalism had. In the 19th century and still today in Europe, the liberal parties were those parties which were in favor of freer market, of cutting down tariffs, of expanding the role of the individual in the economy. -

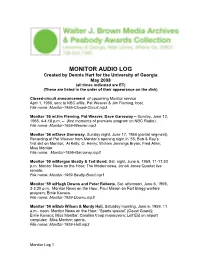

Monitor Audio

MONITOR AUDIO LOG Created by Dennis Hart for the University of Georgia May 2008 (all times indicated are ET) (These are listed in the order of their appearance on the disk) Closed-circuit announcement of upcoming Monitor service April 1, 1955, sent to NBC affils, Pat Weaver & Jim Fleming, host. File name: Monitor-1955-Closed-Circuit.mp3 Monitor ’55 w/Jim Fleming, Pat Weaver, Dave Garroway – Sunday, June 12, 1955, 4-4:18 p.m. -- (first moments of premiere program on NBC Radio). File name: Monitor-1955-Weaver.mp3 Monitor ‘56 w/Dave Garroway, Sunday night, June 17, 1956 (partial segment) Recording of Pat Weaver from Monitor’s opening night in ’55; Bob & Ray’s first skit on Monitor; Al Kelly; O. Henry; William Jennings Bryan; Fred Allen; Miss Monitor. File name: Monitor-1956-Garroway.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Morgan Beatty & Ted Bond, Sat. night, June 6, 1959, 11-11:30 p.m. Monitor News on the Hour; The Modernaires; Jonah Jones Quartet live remote. File name: Monitor-1959-Beatty-Bond.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Hugh Downs and Peter Roberts, Sat. afternoon, June 6, 1959, 3-3:30 p.m. Monitor News on the Hour; Paul Mason on Fort Bragg warfare program; Ernie Kovacs. File name: Monitor-1959-Downs.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Bob Wilson & Monty Hall, Saturday morning, June 6, 1959, 11 a.m.- noon. Monitor News on the Hour; “Sports special” (Coast Guard); Ernie Kovacs; Miss Monitor; Carolina troop maneuvers; Leif Eid on airport computer; Miss Monitor; sports. File name: Monitor-1959-Hall.mp3 Monitor Log 1 Monitor ’61 w/Frank McGee, Sunday night, New Year’s Eve, [December 31, 1961] 7-8 p.m. -

The News Media and the Disorders: the Kerner Commission's Examination of Race

The News Media and the Disorders: The Kerner Commission's Examination of Race Riots and Civil Disturbances, 1967-68 A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Thomas J. Hrach June 2008 © 2008 Thomas J. Hrach All Rights Reserved ii This dissertation titled The News Media and the Disorders: The Kerner Commission's Examination of Race Riots and Civil Disturbances, 1967-68 by THOMAS J. HRACH has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Patrick S. Washburn Professor of E. W. Scripps School of Journalism Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication iii Abstract HRACH, THOMAS J., Ph.D., June 2008, Journalism The News Media and the Disorders: The Kerner Commission's Examination of Race Riots and Civil Disturbances, 1967-68 (276 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Patrick S. Washburn The National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known informally as the Kerner Commission, issued a 425-page report on March 1, 1968, that brought the attention of the nation to the issues of race and poverty. President Lyndon Johnson appointed the commission on July 27, 1967, after a summer of urban rioting in hopes of preventing future violence. One of the questions Johnson asked the commission to answer was: “What effect do the mass media have on the riots?” From that question, the commission developed Chapter Fifteen of the Kerner Report titled “The News Media and the Disorders.” Historians and journalists credit the news media chapter with inspiring improvement in how the press covered race and poverty and encouraging an increase in the number of blacks hired into the mainstream media. -

Test of the Endnote System

DISSENTING PARTNERS: THE NATO NUCLEAR PLANNING GROUP 1965-1976 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for A Doctoral Degree of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Franz L. Rademacher, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Carole Fink, Adviser Professor Peter Hahn Professor Alan Beyerchen _________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in History ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the history of the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) in NATO from its establishment through its formative and influential first decade. The current historiography, based on a limited number of primary and secondary sources, sees the NPG as an effective method of nuclear sharing in the early 1960s, as a vehicle utilized by the non-nuclear NATO members to influence United States nuclear planning. Utilizing government sources in the United States, Great Britain, and Germany, this thesis argues that the Nuclear Planning Group was an effective tool of consultation that allowed for a measure of compromise concerning concepts on nuclear war. This consultation apparatus was a significant departure from American treatment of allied concerns in the first fifteen years of NATO. It represented a method of bringing West Germany into a unique relationship that conformed to the Anglo-American views on nuclear planning while also serving to minimize the influence of other non-nuclear states. There existed limits to which the United States was willing to extend nuclear influence to its partners, and in the longer term, the NPG remained a political instrument, that was unable to resolve some of the most difficult problems of nuclear defense it faced in its first decade. -

ABSTRACT Chicken Noodle News: CNN and the Quest for Respect

ABSTRACT Chicken Noodle News: CNN and the Quest for Respect Katy McDowall Director: Sara Stone, Ph.D. This thesis, focusing on Cable News Network, studies how cable news has changed in the past 30 years. In its infancy, CNN was a pioneer. The network proved there was a place for 24-hour news and live story coverage. More than that, CNN showed that 24-hour- news could be done cheaper than most of the era’s major networks. But time has changed cable news. As a rule, it is shallower, more expensive and more political, and must adapt to changing technologies. This thesis discusses ways CNN can regain its place in the ratings against competitors like Fox News and MSNBC, while ultimately improving cable news by sticking to its original core value: the news comes first. To accomplish this, this thesis looks at CNN’s past and present, and, based upon real examples, makes projections about the network’s (and journalism’s) future. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: __________________________________________ _ Dr. Sara Stone, Department of Journalism, Public Relations and New Media APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ___________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director DATE:__________________________ CHICKEN NOODLE NEWS: CNN AND THE QUEST FOR RESPECT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Katy McDowall Waco, Texas May 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………iv CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………...1 The Pre-CNN Television News World and the Big Three Ted Turner and His Plan The CNN Team A Television Newspaper: The Philosophies CNN Was Founded On From Now on and Forever: CNN Goes on the Air “Chicken Noodle News” Not So Chicken Noodle: CNN Stands its Ground The Big Three (Try To) Strike Back CNN at its Prime 2. -

General Catalog of the University of Illinois Film Center

791.43074 Un3i 1984 sun. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN STACKS 1984 Cumulative Supplement (1982-84) to the 1981 General Catalog of the University of Illinois Film Center sin 1^ ML St?!!!* 111 1 f»i"f»> 1 // * V Uddd D\0 ODD DDD **** WM J 1 Plan a Year Full of Disney Classics Without Delay! Rent these Disney films at low rates from the University of IN USA 1-800-FOR-FILM (1-800-367 3456) IN ILL 1-800-252-1357 Illinois Film Center Request a copy of specific exhibition policies (217) 333-1360 that apply to these titles Film Title Price Film Title Pric< Absent-Minded Professor, The (b/w) $ 60.00 Milestones in Animation (color/b/w) $ 50.0 Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin. The $ 55.00 Million Dollar Dixie Deliverance, The $ 55.0 Almost Angels $ 55.00 Million Dollar Duck, The $ 65 Apple Dumpling Gang, The $ 95.00 Miracle of the White Stallions, The $ 55.0 Apple Dumpling Gang Rides Again, The $ 80.00 Monkeys, Go Home! $ 55.0 Babes in Toyland $100.00 Monkey's Uncle, The $55 Barefoot Executive, The $ 55.00 Napoleon and Samantha $ 55. ON Bears & I, The $ 65.00 Night Crossing new $ 95 01 Bedknobs and Broomsticks $ 95.00 No Deposit, No Return $ 80 O Behind the Scenes at Walt Disney Studios with North Avenue Irregulars, The $ 90 the Reluctant Dragon (color/b/w) $ 55.00 Now You See Him, Now You Don't $ 75 0d Big Red $ 55.00 Omega Connection, The $ 55 O Blackbeard's Ghost new $ 8000 Once Upon a Mouse $ 40 Of Black Hole, The $100.00 One Little Indian $ 55.01 Boatniks, The $ 65.00 One and Only, Genuine Original Family Band, The $ 55.01 -

NBC Expands Pact with Australian Television

THE NEW YORK TIMES THE LIVINI TV Notes Jeremy Gerard ■ The election and its coverage ■ Revisiting Peacock Down Under How hungry are the networks for ■ new markets? NBC has just ex- Dallas, November 1963 Peacock joins koala: panded its six-year-old agreement with the Australian Television Net- NBC expands pact with Australian television. work, which already has access to all NBC programming. Under the new agreement, NBC has the option of ac- pact of polls and the influence of cam- quiring 15 percent of Qintex Austral- Election Coverage paign managers on political coverage ia, which owns the Australian net- Pre- and post-election programs: in the media. work. That network would become Tonight, public television will focus NBC's first overseas affiliate. most of its biggest political guns on Nov. 22, 1963, Revisited the outcome of the Presidential elec- From the You Were There depart- tion. A two-hour program, optimisti- ment: On Nov. 22, the Arts & Enter- Sweeping Shows cally called "The Last Word," will tainment cable channel, which is feature commentary by Robert Mac- owned by NBC, ABC and the Hearst November is a "sweeps" month, Neil, Jim Lehrer and Charlayne Corporation, will devote six hours to a when television advertising rates are Hunter-Gault, of the "MacNeil/Leh- replay of NBC's coverage of the as- adjusted for Vie coming quarter on rer Newshour"; Paul Duke, the host sassination of President Kennedy in the basis of ratings. That means the of "Washington Week in Review"; 1963, including the live reports from networks will be doing everything Louis Rukeyser, of "Wall Street correspondents Chet Huntley, David they can get away with to attract Week"; William Greider, a corre- Brinkley, Robert MacNeil, Frank viewers — from the steamiest mini- spondent for "Frontline" and for McGee, and the host of this special series to lurid special news reports to Rolling Stone magazine, and Bill broadcast, Edwin Newman, who was nose-breaking news on the talk Moyers, who probably doesn't need a member of the network news team shows. -

Voices for Careers. INSTITUTION New Jersey State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 069 870 VT 017 460 AUTHOR York, Edwin G.; Kapadia, Madhu TITLE Voices for Careers. INSTITUTION New Jersey State Dept. of Education, Trenton. Div. of Vocational Education. PUB DATE Sep 72 NOTE 72p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Adult Vocational Education; *Annotated Bibliographies; *Career Education; Educational Resources; Indexes (Locaters) ; Post Secondary Education; *Resource Centers; Secondary Grades; *Video Cassette Systems; Vocational Development; *Vocational Interests IDENTIFIERS *Career Exploration ABSTRACT Listed in this annotated bibliography are 502 cassette tapes of value to career exploration for Grade 7 through the adult level, whether as individualized instruction, small group study, or total class activity. Available to New Jersey educators at no charge, this Voices for Careers System is also available for duplication on request from the New Jersey Occupational Resource Center in Edison. Procedures for securing the cassettes are described, noting that this service exists to serve the needs of individual educators and is not designed to stock libraries.. Listed and described under 25 major topics divided into subtopics, these tapes utilize the voices of well-known Americans to stimulate vocational interests. A name index and topical index are included, as well as the phone numbers for the New Jersey Occupational Research and Development Center. (AG) A FI Tv (4): HEALTH OF EDUCATION HIE% REPRO PICT; VI D ROM !. UP ORGANtitioN milt; FOR CAREERS .. ONTS iiidtf 1.. OR °Pi% I D DU `:tit NICESSRILY 1C.IAt ()Mu OF TDo by S1110f4 CM POLIO Edwin G. York Voices for Careers: 502 Cassette Tapes of SPECIAL Coordinator, N.J. 04 Value to the Career Exploration of Youth PAPER Occupational Resource Centers and Adults.