Meet the Press Discussion, August 21 1966

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69

Analysis of Talk Shows Between Obama and Trump Administrations by Jack Norcross — 69 An Analysis of the Political Affiliations and Professions of Sunday Talk Show Guests Between the Obama and Trump Administrations Jack Norcross Journalism Elon University Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in an undergraduate senior capstone course in communications Abstract The Sunday morning talk shows have long been a platform for high-quality journalism and analysis of the week’s top political headlines. This research will compare guests between the first two years of Barack Obama’s presidency and the first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. A quantitative content analysis of television transcripts was used to identify changes in both the political affiliations and profession of the guests who appeared on NBC’s “Meet the Press,” CBS’s “Face the Nation,” ABC’s “This Week” and “Fox News Sunday” between the two administrations. Findings indicated that the dominant political viewpoint of guests differed by show during the Obama administration, while all shows hosted more Republicans than Democrats during the Trump administration. Furthermore, U.S. Senators and TV/Radio journalists were cumulatively the most frequent guests on the programs. I. Introduction Sunday morning political talk shows have been around since 1947, when NBC’s “Meet the Press” brought on politicians and newsmakers to be questioned by members of the press. The show’s format would evolve over the next 70 years, and give rise to fellow Sunday morning competitors including ABC’s “This Week,” CBS’s “Face the Nation” and “Fox News Sunday.” Since the mid-twentieth century, the overall media landscape significantly changed with the rise of cable news, social media and the consumption of online content. -

WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library White House Communications Agency (WHCA): Videotapes of Public Affairs, News, and Other Television Broadcasts, 1973-77 WHCA selectively created, or acquired, videorecordings of news and public affairs broadcasts from the national networks CBS, NBC, and ABC; the public broadcast station WETA in Washington, DC; and various local station affiliates. Program examples include: news special reports, national presidential addresses and press conferences, local presidential events, guest interviews of administration officials, appearances of Ford family members, and the 1976 Republican Convention and Ford-Carter debates. In addition, WHCA created weekly compilation tapes of selected stories from network evening news programs. Click here for more details about the contents of the "Weekly News Summary" tapes All WHCA videorecordings are listed in the table below according to approximate original broadcast date. The last entries, however, are for compilation tapes of selected television appearances by Mrs. Ford, 1974-76. The tables are based on WHCA’s daily logs. “Tape Length” refers to the total recording time available, not actual broadcast duration. Copyright Notice: Although presidential addresses and very comparable public events are in the public domain, the broadcaster holds the rights to all of its own original content. This would include, for example, reporter commentaries and any supplemental information or images. Researchers may acquire copies of the videorecordings, but use of the copyrighted portions is restricted to private study and “fair use” in scholarship and research under copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code). Use the search capabilities of your PDF reader to locate specific names or keywords in the table below. -

Nov. 22, 1964, New York, Meet the Press

p¿~ et'~ gJ~ 9k{JJ~o/ .9k .HaUcnaI MEET THE PRESS . ,.' .. as broadcast' nationwide by the National Broadcasting Com pany, Ine., are printed and made available to the public·to further interest in impartial diseussions of questions deet ing the publie welfare. Transeripts may be obtained by send (iJ ing a stamped, self-addressed envelope and ten ~nts for each eopy to: .. M:E.E.T T H E P R E S S f ~,() Y'~ cc~ ~ Jt-ue g'I'<lÜ Jne. 8"9 ~ !/ín.et; JI(<ff. 1~ ... ~ 'C 2(}(H8 ~ o/tite 1· gJ~'7 LAWRENCE E. SPIVAK MEET THE PRESS iB teZecg,st every Sunday over the NBC TeZevi8ion Net ~tuIIIL- MISS JUANA CASTRO work. This program originated from the NBC Studios in Washington, D. C. VOLUME 8 SU~Di\Y' NOVEMBER 22,1964 NUMBER 43 Television Broadcast 6:00 P.H. EST Radio Broadcast 6:30 P.M. EST ~ ~~ ..Ine. ~~ and ~~~~ e 1'1'a8-1'l' SO,9 ~ %eet; JV <ff. 1f/~, f). ~ 200lS 10 centa per copy ,..."~ J [/Janel: MAYCRAIG, Portland (Me.)Press Herald HERB KAPLOW, NBC News DAVID KRASLOW, Los Angeles Times I LAWRENCE E. SPIVAK, Permanent Panel Member 1 M E E T T H E P R E S S MR. BROOKS: This is Ned Brooks, inviting you to MEET THE PRESS. Our guest today on MEET THE PRESS is the sister of Premier Fidel Castro of Cuba, Miss Juana Castro. She was closely aIlied with him in the revolution against Batista. Severa! months moderator: NED BROOKS ago she fled from Cuba to Mexico, and she is now devoting herself to Castro's overthrow. -

Civil Rights Movement and the Legacy of Martin Luther

RETURN TO PUBLICATIONS HOMEPAGE The Dream Is Alive, by Gary Puckrein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: Excerpts from Statements and Speeches Two Centuries of Black Leadership: Biographical Sketches March toward Equality: Significant Moments in the Civil Rights Movement Return to African-American History page. Martin Luther King, Jr. This site is produced and maintained by the U.S. Department of State. Links to other Internet sites should not be construed as an endorsement of the views contained therein. THE DREAM IS ALIVE by Gary Puckrein ● The Dilemma of Slavery ● Emancipation and Segregation ● Origins of a Movement ● Equal Education ● Montgomery, Alabama ● Martin Luther King, Jr. ● The Politics of Nonviolent Protest ● From Birmingham to the March on Washington ● Legislating Civil Rights ● Carrying on the Dream The Dilemma of Slavery In 1776, the Founding Fathers of the United States laid out a compelling vision of a free and democratic society in which individual could claim inherent rights over another. When these men drafted the Declaration of Independence, they included a passage charging King George III with forcing the slave trade on the colonies. The original draft, attributed to Thomas Jefferson, condemned King George for violating the "most sacred rights of life and liberty of a distant people who never offended him." After bitter debate, this clause was taken out of the Declaration at the insistence of Southern states, where slavery was an institution, and some Northern states whose merchant ships carried slaves from Africa to the colonies of the New World. Thus, even before the United States became a nation, the conflict between the dreams of liberty and the realities of 18th-century values was joined. -

(FCC) Complaints About Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020

Description of document: Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Complaints about Saturday Night Live (SNL), 2019-2021 and Dave Chappelle, 11/1/2020-12/10/2020 Requested date: 2021 Release date: 21-December-2021 Posted date: 12-July-2021 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request Federal Communications Commission Office of Inspector General 45 L Street NE Washington, D.C. 20554 FOIAonline The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Federal Communications Commission Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau Washington, D.C. 20554 December 21, 2021 VIA ELECTRONIC MAIL FOIA Nos. -

The National News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September (1973)

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Formation of the National News Council Judicial Ethics and the National News Council 8-1973 The aN tional News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September The aN tional News Council, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/nnc Recommended Citation The aN tional News Council, Inc., The National News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September (1973). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/nnc/168 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Judicial Ethics and the National News Council at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Formation of the National News Council by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 197J 19 By lORN I. O'CONNOR TelevisIon NE of the more significant con are received. The letter concluded that tuted "a controversial Issue ext public In three ·centralized conduits? If the frontations currently taking place "in our view there is no~hing contro importance," networks do distort, however uninten Oin the television arena involves versial or debatable in the proposition Getting no response from the net tionally, who will force them to clarify? the case of Accuracy in Media, that nat aU pensions meet the expecta work that it considered acceptable, AIM In any journalism, given the pressure Inc., a nonprofit, self-appointed "watch tions' of employes or serve all persons took its case to the FCC, and last of deadlines, mistakes are inevitable. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

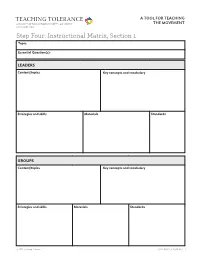

Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 Topic: Essential Question(s): LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards GROUPS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: EVENTS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards HISTORICAL CONTEXT Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: OPPOSITION Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards TACTICS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG STEP FOUR: INSTRUCTIONAL MATRIX, SECTION 1 (CONTINUED) Topic: CONNECTIONS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Strategies and skills Materials Standards © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Four: Instructional Matrix, Section 1 (SAMPLE) Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? LEADERS Content/topics Key concepts and vocabulary Martin Luther King Jr., A. -

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

Investigating the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Topic: Civil Rights History Grade level: Grades 4 – 6 Subject Area: Social Studies, ELA Time Required: 2 -3 class periods Goals/Rationale Bring history to life through reenacting a significant historical event. Raise awareness that the civil rights movement required the dedication of many leaders and organizations. Shed light on the power of words, both spoken and written, to inspire others and make progress toward social change. Essential Question How do leaders use written and spoken words to make change in their communities and government? Objectives Read, analyze and recite an excerpt from a speech delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Identify leaders of the Civil Rights Movement; use primary source material to gather information. Reenact the March on Washington to gain a deeper understanding of this historic demonstration. Connections to Curriculum Standards Common Core State Standards CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.1 Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.2 Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text. CCSS.ELA-Literacy RI.5.4 Determine the meaning of general academic and domain-specific words and phrases in a text relevant to a grade 5 topic or subject area. CCSS.ELA-Literacy SL.5.6 Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and tasks, using formal English when appropriate to task and situation. National History Standards for Historical Thinking Standard 2: The student comprehends a variety of historical sources. -

Ruth Marcus Experience The

RUTH MARCUS EXPERIENCE THE WASHINGTON POST 2016-Present: Deputy editorial page editor. Oversee oped pages and all signed opinion content. Review oped submissions, hire and manage columnists and bloggers, develop multi- platform content including video, chart strategic direction of opinion section and develop digital strategy. As member of editorial board attend editorial board meetings and help shape editorial positions. 2006-Present: Columnist. Write opinion column for oped page and, beginning in 2008, for syndicated newspaper clients, focusing on domestic politics and policy. Finalist, Pulitzer Prize for commentary, 2007. “The week” columnist of the year, 2008. 2003-2015: Editorial writer. Write editorials on domestic policy and politics, including budget and taxes, health care, money and politics. 1999-2003: Deputy National Editor. Oversee staff coverage of campaign finance and lobbying and national politics; direct coverage of 2000 recount. 1986-1999: National Staff Reporter covering White House, Supreme Court, Justice Department, national politics, money and politics. 1984-1987: Metro staff reporter covering local development and legal issues. Wrote weekly column on law and lawyers. Covered “Year of the Spy” espionage cases. EXTRACURRICULAR: 2017-Present: MSNBC/NBC news contributor. Appear several times weekly on MSBC shows, including Morning Joe, Andrea Mitchell Reports, Hardball, Last Word, Meet the Press and Meet the Press Daily. Previously: Regular guest on ABC’s “This Week,” CBS “Face the Nation,” CNN, Fox News Frequent guest and moderator on panels, including Atlantic Festival, Aspen Ideas Festival, New Yorker Festival, Brookings Institution. EDUCATION 1981-1984: Harvard Law School, magna cum laude, Harvard Law Review 1975-1979: Yale College, cum laude, with distinction in history Error! Bookmark not defined. -

Politics of Parody

Bryant University Bryant Digital Repository English and Cultural Studies Faculty English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles Publications and Research Winter 2012 Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Bryant University Ethan Thompson Texas A & M University - Corpus Christi, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Day, Amber and Thompson, Ethan, "Live From New York, It's the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody" (2012). English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles. Paper 44. https://digitalcommons.bryant.edu/eng_jou/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Research at Bryant Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in English and Cultural Studies Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bryant Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Live from New York, It’s the Fake News! Saturday Night Live and the (Non)Politics of Parody Amber Day Assistant Professor English and Cultural Studies Bryant University 401-952-3933 [email protected] Ethan Thompson Associate Professor Department of Communication Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi 361-876-5200 [email protected] 2 Abstract Though Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” has become one of the most iconic of fake news programs, it is remarkably unfocused on either satiric critique or parody of particular news conventions. -

NBC, "The Nation's Future"

THE NATION'S FUTURE Sunday, October 15, 1961 NBC Television (5 :00-6 :00 PM) "THE ADMINISTRATION'S DOMESTIC RECORD: SUCCESS OR FAILURE?" MODERATOR: EDWIN NEWMAN GUESTS : THE HON. ABRAHAM RIBICOFF SENATOR EVERETT M. DIRKSEN ANNOUNCER: The Nation's Future, October 15, 1961. This is the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, Abraham A. Ribicoff. Secretary Ribicoff believes that the Kennedy Administration's Domestic Record represents a success on the "New Frontier". 'This is Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen, Republican of Illinois and Senate minority leader. Senator Dirksen believes that the Administration's Domestic Record represents a failure on the "New Frontier". The Administration's Domestic Record: Success or Failure? Our speakers, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, Abraham A. Ribicoff, and Senator Everett McKinely Dirksen, Republican of Illinois. ANNOUNCER: In our audience, government officials, political t CONT 'D) figures, journalists, the general public. Now, here is our moderator, the noted news corres- pondent, Edw in Newman. Good evening. Welcome to the primary debate in the new season of NE he Nation ls Future". In the coming months we wiu'be bringing to you again the foremost spokesmen of our time in major debates on topics of nati6nal and international importance. Again it will be my pleasure to act as moderator for the series. Tonight, a debate on the Kennedy Administrat ion Is Domestic Record. This is an appropriate time for such a debate. Congress adjourned late last month and its achieve- ments or failures are being vigorously argued. Criticism of the Administration record has intensi- fied and Administration spokesmen have come to the defense of that record.