Debate Between the President and Former Vice President Walter F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September (1973)

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Formation of the National News Council Judicial Ethics and the National News Council 8-1973 The aN tional News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September The aN tional News Council, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/nnc Recommended Citation The aN tional News Council, Inc., The National News Council's News Clippings, 1973 August- 1973 September (1973). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/nnc/168 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Judicial Ethics and the National News Council at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Formation of the National News Council by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16, 197J 19 By lORN I. O'CONNOR TelevisIon NE of the more significant con are received. The letter concluded that tuted "a controversial Issue ext public In three ·centralized conduits? If the frontations currently taking place "in our view there is no~hing contro importance," networks do distort, however uninten Oin the television arena involves versial or debatable in the proposition Getting no response from the net tionally, who will force them to clarify? the case of Accuracy in Media, that nat aU pensions meet the expecta work that it considered acceptable, AIM In any journalism, given the pressure Inc., a nonprofit, self-appointed "watch tions' of employes or serve all persons took its case to the FCC, and last of deadlines, mistakes are inevitable. -

May 2001 03 Jazz Ed

ALL ABOUT JAZZ monthly edition — may 2001 03 Jazz Ed. 04 Pat Metheny: New Approaches 09 The Genius Guide to Jazz: Prelude EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aaron Wrixon 14 The Fantasy Catalog: Tres Joses ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael Martino 18 Larry Carlton and Steve Lukather: Guitar Giants CONTRIBUTORS: 28 The Blue Note Catalog: All Blue Glenn Astarita, Mathew Bahl, Jeff Fitzgerald, Chris Hovan, Allen Huotari, Nils Jacobson, Todd S. Jenkins, Joel Roberts, Chris M. Slawecki, Derek Taylor, Don Williamson, 32 Joel Dorn: Jazz Classics Aaron Wrixon. ON THE COVER: Pat Metheny 42 Dena DeRose: No Detour Ahead PUBLISHER: 48 CD Reviews Michael Ricci Contents © 2001 All About Jazz, Wrixon Media Ventures, and contributors. Letters to the editor and manuscripts welcome. Visit www.allaboutjazz.com for contact information. Unsolicited mailed manuscripts will not be returned. Welcome to the May issue of All About Jazz, Pogo Pogo, or Joe Bat’s Arm, Newfoundland Monthly Edition! (my grandfather is rolling over in his grave at This month, we’re proud to announce a new the indignity I have just committed against columnist, Jeff Fitzgerald, and his new, er, him) — or WHEREVER you’ve been hiding column: The Genius Guide to Jazz. under a rock all this while — and check some Jeff, it seems, is blessed by genius and — of Metheny’s records out of the library. as is the case with many graced by voluminous The man is a guitar god, and it’s an intellect — he’s not afraid to share that fact honour and a privilege to have Allen Huotari’s with us. -

Lee Morgan Chronology 1956–1972 by Jeffery S

Delightfulee Jeffrey S. McMillan University of Michigan Press Lee Morgan Chronology 1956–1972 By Jeffery S. McMillan This is an annotated listing of all known Lee Morgan performances and all recordings (studio, live performances, broadcasts, telecasts, and interviews). The titles of studio recordings are given in bold and preceded by the name of the session leader. Recordings that appear to be lost are prefaced with a single asterisk in parentheses: (*). Recordings that have been commercially issued have two asterisks: **. Recordings that exist on tape but have never been commercially released have two asterisks in parentheses: (**). Any video footage known to survive is prefaced with three asterisks: ***. Video footage that was recorded but appears to now be lost is prefaced with three asterisks in parentheses: (***). On numerous occasions at Slugs’ Saloon in Manhattan, recording devices were set up on the stage and recorded Morgan’s performances without objection from the trumpeter. So far, none of these recordings have come to light. The information herein is a collation of data from newspapers, periodicals, published and personal interviews, discographies, programs, pamphlets, and other chronologies of other artists. Morgan’s performances were rarely advertised in most mainstream papers, so I drew valuable information primarily from African-American newspapers and jazz periodicals, which regularly carried ads for nightclubs and concerts. Entertainment and nightlife columnists in the black press, such as “Woody” McBride, Masco Young, Roland Marsh, Jesse Walker, Art Peters, and Del Shields, provided critical information, often verifying the personnel of an engagement or whether an advertised appearance occurred or was cancelled. Newspapers that I used include the Baltimore Afro-American (BAA), Cleveland Call & Post (C&P), Chicago Defender (CD), New Jersey Afro-American (NJAA), New York Amsterdam News (NYAN), Philadelphia Tribune (PT), and Pittsburgh Courier (PC). -

NBC, "The Nation's Future"

THE NATION'S FUTURE Sunday, October 15, 1961 NBC Television (5 :00-6 :00 PM) "THE ADMINISTRATION'S DOMESTIC RECORD: SUCCESS OR FAILURE?" MODERATOR: EDWIN NEWMAN GUESTS : THE HON. ABRAHAM RIBICOFF SENATOR EVERETT M. DIRKSEN ANNOUNCER: The Nation's Future, October 15, 1961. This is the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, Abraham A. Ribicoff. Secretary Ribicoff believes that the Kennedy Administration's Domestic Record represents a success on the "New Frontier". 'This is Senator Everett McKinley Dirksen, Republican of Illinois and Senate minority leader. Senator Dirksen believes that the Administration's Domestic Record represents a failure on the "New Frontier". The Administration's Domestic Record: Success or Failure? Our speakers, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, Abraham A. Ribicoff, and Senator Everett McKinely Dirksen, Republican of Illinois. ANNOUNCER: In our audience, government officials, political t CONT 'D) figures, journalists, the general public. Now, here is our moderator, the noted news corres- pondent, Edw in Newman. Good evening. Welcome to the primary debate in the new season of NE he Nation ls Future". In the coming months we wiu'be bringing to you again the foremost spokesmen of our time in major debates on topics of nati6nal and international importance. Again it will be my pleasure to act as moderator for the series. Tonight, a debate on the Kennedy Administrat ion Is Domestic Record. This is an appropriate time for such a debate. Congress adjourned late last month and its achieve- ments or failures are being vigorously argued. Criticism of the Administration record has intensi- fied and Administration spokesmen have come to the defense of that record. -

The Cooker (Blue Note)

Lee Morgan The Cooker (Blue Note) The Cooker Lee Morgan, trumpet; Pepper Adams, baritone sax; Bobby Timmons, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; Philly Joe Jones, drums. 1. A Night In Tunisia (Dizzy Gillespie) 9:22 Produced by ALFRED LION 2. Heavy Dipper (Lee Morgan) 7:05 Cover Photo by FRANCIS WOLFF 3. Just One Of Those Things (Cole Porter) 7:15 Cover Design by REID MILES 4. Lover Man (Ramirez-Davis-Sherman) 6:49 Recording by RUDY VAN GELDER 5. New-Ma (Lee Morgan) 8:13 Recorded on September 29, 1957 Lee Morgan, not yet twenty years old at this writing, is here represented for the fifth time as the leader of a Blue Note recording session. His fantastically rapid growth (technically and musically) as witness previous efforts, along with this one, places him beyond the "upcoming" or "potential" status into the ranks of those whose potential has been realized. Lee stands, right now, as one of the top trumpet players in modern jazz. As the title states, Lee is a "Cooker." He plays hot. His style, relating to the Gillespie- Navarro-Brown school, is strong and vital. There is enthusiasm in his music. A kind of "happy to be playing" feeling that is immediately communicated to the listener. Lee's later three Blue Note offerings have been set within the sparkling context of tunes written, mostly, by the provocative Benny Golson. Herein he reverts back to the format of his first recording, playing in a less "strict" atmosphere and just plain wailing throughout. "A Night In Tunisia" (Dizzy's tune which has been lee's showcase vehicle since he joined the Gillespie organization) leads off the set. -

Speaking Freely. PUB DATE 15 Sep 74 NOTE 40P.; Interview of Albert Shanker by Edwin Newman on VNBC-TV (New York City, Channel 4, September 15, 1974)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 103 526 UD 014 893 AUTHOR Shanker, Albert TITLE speaking Freely. PUB DATE 15 Sep 74 NOTE 40p.; Interview of Albert Shanker by Edwin Newman on VNBC-TV (New York City, Channel 4, September 15, 1974) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$1.95 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Activism; Community Control; Educational Finance; *Educational Needs; Educational Planning; Educational Policy; Educational Problems; Ethnic Groups; Governance; *Politics; *Public Policy; School Community Relationship; *Teacher Associations; *Teacher Militancy ABSTRACT In this interview, Albert Shanker, president of the United Federation of Teachers of New York City, executive vice president of the American Federation of Teachers, and vice president of the AFL/CIO, discussed such topics as the following: his participation in a meeting of labor leaders with President Ford on September 11; the potential influence of teachers if they were organized; the intention of the government to handle the current crisis by maintaining a hard money policy; the deterioration in the quality of education over the last four or five years; the sort of social progress which could be brought about by teacher action; the limitations of collective bargaining as an instrument; the prospect that a teachers' union or unions will be able to do what held like them to do without a merger between the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and the National Education Association (NEA); attacks on public education; the dissatisfaction with the public schools among, not only middle class people, but among working class people who feel that the schools don't do for their children what they ought to do; community control; the prospect of a merger for your own purposes and teachers' own protection between the A.F.T. -

Classical Folk & Blues Jazz Stage & Screen World Music

Fall, 2020 All Prices Good through 11/30/20 Music Classical see pages 3 - 24 Not Our First Goat Rodeo Yo-Yo Ma & Friends A classical-crossover selection SNYC 19439738552 $16.98 Folk & Blues see pages 42 - 49 Sierra Hull: 25 Trips Sierra jumps from her bluegrass roots to entirely new terrain 1CD# RDR 1166100579 $16.98 Jazz see pages 38 - 41 Diana Krall This Dream of You A wonderful collection of gems from the American Songbook 1CD# IMPU B003251902 $19.98 Stage & Screen see pages 25 - 29 Ennio Morricone Partnered with: Once Upon A Time Arrangements for Guitar 1CD# BLC 95855 $12.98 World Music see pages 34 - 37 Afwoyo – Afro Jazz Milégé derive inspiration from the diverse musical traditions of Uganda VT / KY / TN CD# NXS 76108 $16.98 see page 2 HBDirect Mixed-Genre Catalog HBDirect is pleased to present our newest Mixed-Genre catalog – bringing you the widest selection of classical, jazz, world music, folk, blues, band music, oldies and so much more! Call your Fall 2020 order in to our toll-free 800 line, mail it to us, or you can search for your selections on our website where you’ll also find thousands more recordings to choose from. Not Our First Goat Rodeo: Yo-Yo Ma & Friends Classical highlights in this issue include a tribute to Orfeo Records in honor of the label’s 40th Nine years ago, classical legends Yo Yo Ma, Stuart Duncan, Chris Thile, and anniversary, music of African American composers on page 8, plus new releases, videos, boxed sets Edgar Meyer released Goat Rodeo, and now they return with their masterful, and opera. -

Scholar Adventurers Also by Richard D

ichard THE SCHOLAR ADVENTURERS ALSO BY RICHARD D. ALTICK Preface to Critical Reading The Cowden Clarkes The English Common Reader: A Social History of the Mass Reading Public, 1800-1900 The Art of Literary Research Lives and Letters: A History of Literary Biography in England and America Browning's Roman Murder Story: A Reading of The Ring and the Book (with James F. Loucks II) To Be in England Victorian Studies in Scarlet Victorian People and Ideas The Shows of London Paintings from Books: Art and Literature in Britain, 1760-1900 Deadly Encounters: Two Victorian Sensations EDITIONS Thomas Carlyle: Past and Present Robert Browning: The Ring and the Book THE Scholar Adventurers RICHARD D. ALTICK Ohio State University Press, Columbus Copyright ©1950, 1987 by Richard D. Altick. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publicatlon Data Altick, Richard Daniel, 1915- The scholar adventurers. Reprint. Originally published: New York : Macmillan, 1950. With new pref. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English literature—Research. 2. Learning and scholarship—History. 3. Great Britain—Intellectual life. I. Title. P56.A7 1987 820'.72'0922 87-11064 ISBN O-8142-O435-X CONTENTS Preface to the Ohio State University Press Edition vii Introduction: The Unsung Scholar 1 I. The Secret of the Ebony Cabinet 16 II. The Case of the Curious Bibliographers 37 III. The Quest of the Knight-Prisoner 65 IV. Hunting for Manuscripts 86 V. Exit a Lady, Enter Another 122 VI. A Gallery of Inventors 142 VII. The Scholar and the Scientist 176 VIII. Secrets in Cipher 200 IX. The Destructive Elements 211 X. -

Wnbc Television

From The Collected Works of Milton Friedman, compiled and edited by Robert Leeson and Charles G. Palm. Interview. Interviewed by Edwin Newman. Speaking Freely (WNBC), 4 May 1969. MR. NEWMAN: Speaking Freely today is Milton Friedman. Milton Friedman is a professor of economics at the University of Chicago, he is one of the best known and influential economists in the world. He’s an advocate of what might be called the free market approach to the country’s problems. Professor Friedman is celebrated as a critic and opponent of government intervention. He was a principal advisor to Barry Goldwater during the Presidential campaign in 1964. Mr. Friedman, for a number of reasons, one of them of course your association with Senator Goldwater but more specifically the 13 or so books you’ve written and your whole career as an economist, you are generally described as a conservative. But you like to call yourself a liberal. Now, most people who call themselves liberal probably would push you out of the door, so why do you choose that label? MR. FRIEDMAN: The liberal, if you look it up in the dictionary, has to do with freedom—liberalism is the doctrines of and pertaining to freedom. And the basic component of my belief is the belief that we should adopt arrangements which will give each individual separately as much freedom as possible so long as he doesn’t interfere with the freedom of others. Traditionally and historically, this is the meaning the term liberalism had. In the 19th century and still today in Europe, the liberal parties were those parties which were in favor of freer market, of cutting down tariffs, of expanding the role of the individual in the economy. -

The Far Side of the Sky

The Far Side of the Sky Christopher E. Brennen Pasadena, California Dankat Publishing Company Copyright c 2014 Christopher E. Brennen All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from Christopher Earls Brennen. ISBN-0-9667409-1-2 Preface In this collection of stories, I have recorded some of my adventures on the mountains of the world. I make no pretense to being anything other than an average hiker for, as the first stories tell, I came to enjoy the mountains quite late in life. But, like thousands before me, I was drawn increasingly toward the wilderness, partly because of the physical challenge at a time when all I had left was a native courage (some might say foolhardiness), and partly because of a desire to find the limits of my own frailty. As these stories tell, I think I found several such limits; there are some I am proud of and some I am not. Of course, there was also the grandeur and magnificence of the mountains. There is nothing quite to compare with the feeling that envelopes you when, after toiling for many hours looking at rock and dirt a few feet away, the world suddenly opens up and one can see for hundreds of miles in all directions. If I were a religious man, I would feel spirits in the wind, the waterfalls, the trees and the rock. Many of these adventures would not have been possible without the mar- velous companionship that I enjoyed along the way. -

SONNY ROLLINS NEA Jazz Master (1983)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. SONNY ROLLINS NEA Jazz Master (1983) Interviewee: Sonny Rollins (September 7, 1930 - ) Interviewer: Larry Appelbaum with recording interviewer Ken Kimery Date: February 28, 2011 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 50 pp. [Start of Tape 1] Appelbaum: Hello, my name is Larry Appelbaum. Today is February 28, 2011. We are here in the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C., and I’m very pleased to be sitting at this table with Sonny Rollins. Good to see you again. Rollins: Good to see you again, Larry. Appelbaum: Yes. Let me begin by just asking some basics to establish some context. Tell us first of all the date you were born and your full name at birth. Rollins: Oh, I was afraid you were going to ask me that. Ok, my full name at birth was Walter Theodore Rollins, and I was born September 7, Sunday morning, 1930 in Harlem, America uh on 137th Street between Lenox and 7th Avenues. Uh, there was a midwife that delivered me, and that was my–how I entered into this thing we call life. Appelbaum: What were your parents names? Rollins: My father’s name was Walter uh my mother’s name was Valborg, V-A-L-B-O- R-G, which is a Danish name and uh, I can go into that if you want me to. Appelbaum: Tell me first, where were they from? For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Rollins: Yeah well, my father was born in St. -

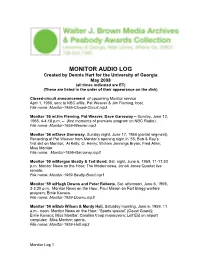

Monitor Audio

MONITOR AUDIO LOG Created by Dennis Hart for the University of Georgia May 2008 (all times indicated are ET) (These are listed in the order of their appearance on the disk) Closed-circuit announcement of upcoming Monitor service April 1, 1955, sent to NBC affils, Pat Weaver & Jim Fleming, host. File name: Monitor-1955-Closed-Circuit.mp3 Monitor ’55 w/Jim Fleming, Pat Weaver, Dave Garroway – Sunday, June 12, 1955, 4-4:18 p.m. -- (first moments of premiere program on NBC Radio). File name: Monitor-1955-Weaver.mp3 Monitor ‘56 w/Dave Garroway, Sunday night, June 17, 1956 (partial segment) Recording of Pat Weaver from Monitor’s opening night in ’55; Bob & Ray’s first skit on Monitor; Al Kelly; O. Henry; William Jennings Bryan; Fred Allen; Miss Monitor. File name: Monitor-1956-Garroway.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Morgan Beatty & Ted Bond, Sat. night, June 6, 1959, 11-11:30 p.m. Monitor News on the Hour; The Modernaires; Jonah Jones Quartet live remote. File name: Monitor-1959-Beatty-Bond.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Hugh Downs and Peter Roberts, Sat. afternoon, June 6, 1959, 3-3:30 p.m. Monitor News on the Hour; Paul Mason on Fort Bragg warfare program; Ernie Kovacs. File name: Monitor-1959-Downs.mp3 Monitor ‘59 w/Bob Wilson & Monty Hall, Saturday morning, June 6, 1959, 11 a.m.- noon. Monitor News on the Hour; “Sports special” (Coast Guard); Ernie Kovacs; Miss Monitor; Carolina troop maneuvers; Leif Eid on airport computer; Miss Monitor; sports. File name: Monitor-1959-Hall.mp3 Monitor Log 1 Monitor ’61 w/Frank McGee, Sunday night, New Year’s Eve, [December 31, 1961] 7-8 p.m.