Oberlin College and the Beginning of the Red Lake Mission / William E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Library Oberlin College Libraries Perspectives

A Newsletter Fall 2017, Issue No. 57 of the Library Oberlin College Libraries Perspectives LIBRARY AND MUSEUM COLLABORATE clifford thompson to speak at friends ON MELLON FOUNDATION GRANT dinner SUPPORTED BY A $150,000 PLANNING CLIFFORD Press published his winning book of essays, GRANT awarded by the Andrew W. Mellon THOMPSON followed by Thompson’s memoir,Twin of Foundation, the libraries recently embarked ’85, recipient Blackness, in 2015. Thompson’s essays on on a series of new initiatives with the Allen of a Whiting books, film, jazz, and American identity Memorial Art Museum (AMAM). With the Writers’ have appeared in publications including aim of strengthening collaboration between Award for the Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice, the libraries and the museum, the grant will nonfiction the Threepenny Review, the Iowa Review, support a number of exciting developments. in 2013 for Commonweal, Film Quarterly, Cineaste, An intensive planning phase will lay the Love for Oxford American, the Los Angeles Review of groundwork for expanded organizational Sale and Books, and Black Issues Book Review. His first and curricular collaboration. An on-campus Other Essays, novel, Signifying Nothing, was published summit planned for June 2018 will bring will be the in 2009. In 2018 Other Press will publish together staff from leading libraries and featured his book J.D. & Me, part memoir and part museums at colleges and universities around Clifford Thompson ’85 speaker reflection on the work of Joan Didion. the country. at the Thompson is also a visual artist; one A goal of the project is to expand staff Friends of the Libraries annual dinner on of his paintings, Going North, appears in expertise and capacity for more intentional, Saturday, November 11. -

000000RG 37/3 SOUND RECORDINGS: CASSETTE TAPES 000000Oberlin College Archives

000000RG 37/3 SOUND RECORDINGS: CASSETTE TAPES 000000Oberlin College Archives Box Date Description Subject Tapes Accession # 1 1950 Ten Thousand Strong, Social Board Production (1994 copy) music 1 1 c. 1950 Ten Thousand Strong & I'll Be with You Where You Are (copy of RCA record) music 2 1 1955 The Gondoliers, Gilbert & Sullivan Players theater 1 1993/29 1 1956 Great Lakes Trio (Rinehart, Steller, Bailey) at Katskill Bay Studio, 8/31/56 music 1 1991/131 1 1958 Princess Ida, Gilbert & Sullivan Players musicals 1 1993/29 1 1958 e.e. cummings reading, Finney Chapel, 4/1958 poetry 1 1 1958 Carl Sandburg, Finney Chapel, 5/8/58 poetry 2 24 1959 Mead Swing Lectures, B.F. Skinner, "The Evolution of Cultural Patterns," 10/28/1959 speakers 1 2017/5 24 1959 Mead Swing Lectures, B.F. Skinner, "A Survival Ethics" speakers 1 2017/5 25 1971 Winter Term 1971, narrated by Doc O'Connor (slide presentation) winter term 1 1986/25 21 1972 Roger W. Sperry, "Lateral Specializations of Mental Functions in the Cerebral Hemispheres speakers 1 2017/5 of Man", 3/15/72 1 1972 Peter Seeger at Commencement (1994 copy) music 1 1 1976 F.X. Roellinger reading "The Tone of Time" by Henry James, 2/13/76 literature 1 1 1976 Library Skills series: Card Catalog library 1 1 1976 Library Skills series: Periodicals, 3/3/76 library 1 1 1976 Library Skills series: Government Documents, 4/8/76 library 1 1 1977 "John D. Lewis: Declaration of Independence and Jefferson" 1/1/1977 history 1 1 1977 Frances E. -

Library Library Perspectives

A Newsletter Spring 2008|Issue No. 38 of the Oberlin College Library Library Perspectives Open Access Gains Ground The James and Susan Neumann The international movement for open access to scholarly research is Jazz Collection rapidly gaining ground, as evidenced Imagine over 100,000 sound recordings by the growth of open access journals, of varying formats: 78 and 45 RPMs, vinyl, digital repositories, and policies that and compact discs. Now imagine shelf after mandate open access to research shelf of books and periodical runs (often sponsored by funding agencies. rare or limited editions), as well as cabinets Most significant for the United of rare posters and playbills, programs and States is a new law requiring public photographs, letters and clippings--many with access to articles resulting from artists’ autographs. Finally, imagine all that research funded by the National you have just conceived falls into a single Institutes of Health (NIH). When subject: jazz. President Bush recently signed into The extraordinary collection you’ve law the Consolidated Appropriations imagined is actually real, and it is being Act of 2007 (H.R. 2764), he approved a donated to Oberlin in stages by James provision directing the NIH to change Neumann ’58 and his wife Susan. Believed to its existing Public Access Policy, be the largest collection related to jazz ever implemented as a voluntary measure in assembled privately, the James and Susan 2005, so that participation is required Neumann Collection has been described by jazz for agency-funded investigators. The expert Daniel Morgenstern as “astonishing in policy requires NIH-funded researchers its scope, breadth, and quality.” to deposit their final peer-reviewed The collection reflects Jim Neumann’s Jim Neumann with lifesize cutout of manuscripts in PubMed Central, lifelong passion. -

Oberlin College Archives Geoffrey T. Blodgett Papers

OBERLIN COLLEGE ARCHIVES GEOFFREY T. BLODGETT PAPERS INVENTORY Subgroup I. Biographical, 1943-46, 1949-66, 1977-78, 1993, 1998-2002, ca. 2011 (1.81 l.f.) Box 1 Awards Alumni Medal, May 2000 Heisman Club Award (remarks by Jane Blodgett), May 2000 Birthday (70th) tribute, 2001 Clippings, 1946, 1952, 1954, 1999-2000, n.d. Curriculum vitae, 1978, 1993, 2000 Employment search Oberlin faculty appointment, 1960 Other teaching job applications, 1959-60 Fellowships, 1959-60 (See also SG III, Series 3) Football Memorabilia/Reunions “Football Memories,” compiled booklet of clippings and photographs, ca. 2011 “Oberlin Football, 1950 and 1951,” booklet for reunion event, May 23, 1998 Graduate Education Graduate school applications: Cornell University, Harvard University, 1953, 1955, n.d. Harvard University, Teaching Assistant for Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., 1956-60 PhD thesis correspondence, 1958-65 Oberlin College Commencement programs, 1953 Diploma, 1953 Memorial Minute by Robert Longsworth, April 16, 2002 Memorial service eulogies and programs, December 8, 2001 Notes on the Oberlin College Men’s Board, ca. 1949-53 Oberlin Community Tax proposal, ca. 1963 Estate of Frederick B. Artz for the Monroe House, Oberlin Historical and Improvement Organization (includes Last Will and Testament), 1977 Tributes, 1993 United States Navy Correspondence, 1951 Officer’s Correspondence Record, “C Jacket,” 1951-65 Officer Service Record for Geoffrey Blodgett, 1953-66 1 OBERLIN COLLEGE ARCHIVES GEOFFREY T. BLODGETT PAPERS Subgroup I. Biographical (cont.) Box 1 (cont.) United States Navy (cont.) Honorable Discharge Certificate, 1966 Box 2 (oversize) Scrapbooks “Invasion of Europe” (news clippings), 1943-45 Oberlin College memorabilia (news clippings, photographs, programs, letters), 1949-53 Subgroup II. -

Library Oberlin College Library Perspectives

A Newsletter Fall 2015, Issue No. 53 of the Library Oberlin College Library Perspectives CONSERVATORY LIBRARY robert darnton to speak at friends COLLABORATES WITH INTERNET ARCHIVE dinner obert Darnton, recently retired THE CONSERVATORY LIBRARY recently began University Librarian of Harvard, will a partnership with the Internet Archive Rbe the featured speaker at the Friends (www.archive.org) to digitally preserve select of the Library annual dinner on Saturday, analog audio recordings from the James R. November 14. Darnton is widely known and Susan Neumann Jazz Collection. The in library circles as a champion of open Neumann Collection includes over 100,000 scholarship; he both founded Harvard’s jazz recordings in various formats (78s, 45s, Office of Scholarly Communication and LPs, CDs, DVDs) as well as print materials, started its Digital Access to Scholarship at including several thousand books on jazz and Harvard (DASH) repository. DASH realized over 100 titles of jazz and blues periodicals. the 2008 resolution approved by the Harvard Thousands of musicians’ photographs and Faculty of Arts and Sciences to provide open autographs, as well as sheet music, artifacts, access to peer-reviewed literature published and ephemera complete the holdings (see by the faculty. DASH quickly became one of Perspectives, Spring 2008, Spring 2012). the more visible open access repositories in Robert Darnton the nation and a model for other institutions. Hundreds of colleges, universities, and scholarship repository in 2011. research institutions have followed course; Darnton is celebrated for his vision of a Oberlin’s General Faculty unanimously free digital library for the nation, created by adopted an open access resolution in 2009, non-profit scholarly organizations. -

Library Perspectives

A Newsletter Spring 2016, Issue No. 54 of the Library Oberlin College Library Perspectives OBERLIN JOINS LEVER PRESS AS mary church terrell papers CHARTER MEMBER his past summer the Oberlin College THE LIBRARY’S Archives received an important LONGSTANDING ADVOCACY Tmanuscript collection, the papers of one for open access to of Oberlin’s most esteemed graduates, Mary scholarly publications Church Terrell. Born Mary Eliza Church took another significant in 1863 to former slaves in Memphis, step forward this year Tennessee, Terrell went on to have a when Oberlin became remarkable career as a writer, public speaker, a charter member in social activist, community organizer, the Lever Press. Lever educator, and civil rights leader. Raymond is a unique publishing Langston, a grandson of Mary Church initiative, built through Terrell, and his wife Jean, who helped to collaboration among the Amherst College preserve and oversee the papers, are the Press, the University of Michigan Press, and donors. the Oberlin Group, a consortium of eighty Terrell led a rich and interesting life, top-ranked liberal arts colleges. with opportunities afforded to few African continued on page 6 Lever Press arose out of a 2013 initiative of the Oberlin Group to study table top scribe brings more library how libraries at liberal arts colleges could content to the internet archive offer a new and compelling publishing alternative for authors of scholarly works. THE LIBRARY has are taken. Images and Lever is particularly interested in projects purchased the metadata about the that focus on interdisciplinarity, that Table Top Scribe book are uploaded engage with major social issues, and that system from the to IA via the Scribe are ideally suited for experiential learning Internet Archive software; Table Top environments by blurring the traditional (IA) and is using Scribe staff then lines between teaching and research. -

Family Histories 1 I. Genealogical Records

THE OBERLIN FILE: GENEALOGICAL RECORDS/ FAMILY HISTORIES I. GENEALOGICAL RECORDS/ FAMILY HISTORIES (Materials are arranged alphabetically by family name.) Box 1 Acton Family, 2003 "Descendents of Edward Harker Acton and Yeoli Stimson Acton" (enr. 1903-05, con; 1905-06, Academy). Consists of a twelve-page typescript copy of a genealogy list, with index, of the Acton Family. Prepared by Emily Acton Phillips, 2003. [Acc. 2003/062] Adams Family, n.d. Genealogy of the Adams family, who settled in Wellington, Ohio in 1823. Includes three individuals who attended the Oberlin Collegiate Institute and Oberlin College: Helen Jennette Adams (Mrs. Simeon W. Windecker), 1859 lit.; Celestia Blinn Adams (Mrs. Arthur C. Ires), enrolled 1855-62; and Mary Ann Adams (Mrs. Charles Conkling), 1839 lit. Compiled by Arthur Stanley Ives. [Acc. 2002/146] Ainsworth Family, 1997 “Ainsworth Family: Stories of Ainsworth Families of Rock Island County, Illinois, 1848-1996.” Compiled by Robert Edwin Ainsworth. (Typescript 150 pages, indexed) Allen, Otis, 2001 Draft of "The Descendants of Otis Allen" an excerpt from "Descendants of Josiah Allen and Mary Reade," by Dan H. Allen. Also filed here is correspondence with the Archives. Baker, Mary Ellen Hull, [ca. 1918?] "For MHB: A Remembrance" by Lois Baker Muehl [typescript; 64 pp; n.d., c. 1981?], received from Phil Tear, February 1, 1983. Story of Mary Ellen Hull Baker (AB 1910), wife of Arthur F. Baker (AB 1911) and mother of Robert A. Baker (AB 1939) and of Mrs. Muehl (AB 1941). Oberlin matters are dealt with on pp. 25-28 and 30-31. For Robert's death, see pp. -

Oberlin College and the Movement to Establish an Archives, 1920-1966 Roland M

OBERLIN COLLEGE AND THE MOVEMENT TO ESTABLISH AN ARCHIVES, 1920-1966 ROLAND M. BAUMANN ABSTRACT Acquiring an appreciation for an archival program's history is one of several steps to be taken by an archivist when involved in planning or self-study exercises. This is an especially important step for a new appointee who succeeds an archivist who held the position for a long period of time. This article describes the conflict and issues surrounding the establishment of an archives at Oberlin College. As a case study, Oberlin is considered somewhat atypical. While the study will add to our understanding of the development of archives in the United States, it was written in order to educate institution- al resource allocators on past issues and to advance specific archival program objectives. The origins of academic archives are as varied as the institutions they serve. The historical consciousness of an institution is sometimes heightened by the need to plan for a commemoration or an anniversary celebration. An inten- tional or unintentional consequence may be the creation of an archival program. In other cases college and university archives or archival programs emerge because a history professor or an administrative officer holds a strong interest in preserving the "memory" of the institution. Archival programs start- ed on a part-time basis or by a distinguished faculty member in retirement ultimately are sustained on a full-time basis because these pioneers showed the way and confirmed the importance of the archives to both administrators and faculty. These and other paths can lead to the founding of an archives. -

Library Library Perspectives

A Newsletter Spring 2009|Issue No. 40 of the Oberlin College Library Library Perspectives New Streamlined The Eric Selch Collection Journal Listing The Conservatory Library is the The Library now subscribes to 360 recipient of an extraordinary collection Core, an A to Z journal listing service that illustrates the development of music, provided by SerialsSolutions. The musical instruments, and music theory in service is designed to make it easy for Europe and the United States. The collection researchers to determine quickly the was assembled by the late Frederick (Eric) Library’s exact holdings for any given R. Selch and donated to Oberlin as part of journal title, whether print or electronic. a much larger gift by his widow, Patricia While holdings information for Bakwin Selch. periodicals has always been included Eric Selch, who had a distinguished in OBIS, users often had to click career in advertising in Britain and the U.S., through multiple screens in order spent a lifetime collecting materials related to learn what issues of a title were to music and musical instruments. At the time available online. Now all holdings and of his death in 2002, he had amassed a wide- access information are consolidated ranging collection of almost 700 instruments; on one screen, saving time and 6,000 books, manuscripts, and printed music; eliminating confusion. In addition to as well as paintings, prints, drawings, and searching the list by title, or browsing photographs depicting the history, design, titles alphabetically, 360 Core allows and use of instruments. Patricia Selch has browsing of journal titles by subject given her husband’s collection to Oberlin and area. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan @ DONALD ELDEN PITZER 1967

This dissertaUon has been microfUmed exactly as received 66-15,123 PITZER, Donald Elden, 1936- PROFESSIONAL REVIVALISM IN NINETEENTH- CENTURY OHIO. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan @ DONALD ELDEN PITZER 1967 All Rights Reserved PROFESSIONAL REVIVALISM IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY OHIO DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Donald Elden Pitzer, A.B. , M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by Adviser <J Department of History PREFACE Professor Henry F. May recently suggested that for the study and understanding of American culture, the recovery of American religious history may well be the most important achievement of the last thirty years. A vast and crucial area of American experience has been rescued from neglect and misunder standing. Puritanism, Edwardsian Calvinism, revivalism, liberal ism, modernism, and the social gospel have all been brought down out of the attic and put back in the historical front parlor.^ Since Ohio shared in the western origins of modern revivalism in the canç meetings of the Second Great Awakening and in each of its major develop ments during the nineteenth century, it is hoped that the present in vestigation might make some contribution to the recovery of this facet of American religious history. Until the past decade, professional revivalism rarely has been the subject of objective research. Its proponents lauded its evangelists and their methods and overestimated its impact. Its critics exaggerated its bizarre aspects and underestimated its significance. Three recent studies have marked a new departure in the analysis and evaluation of revivalism--Timothy L. -

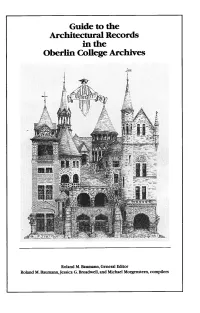

Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oberlin College Archives

Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oberlin College Archives Roland M. Baumann, General Editor Roland M. Baumann, Jessica G. Broadwell, and Michael Morgenstem, compilers ON THE COVER: The cover drawing depicts the Oberlin Stone Age, which lasted for a q>iarter-century after 1885. Included in the montage is the tower of the College Chapel, tower of Coimcil Hall, tower of Talcott Hall, entry of Spear Library Oater, Spear Laboratory), tower and entry of Baldwin Cottage, tower of Warner Hall, and tower and entry of Peters Hall. Artist is Herbert Fairchild Steven, an 1890s student who studied art. Drawing appears in the 1897 Hi-O-Hi, page 13. Unless otherwise noted,.aU photographs are from the holdings of the Oberlin College Archives. Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oberlin College Archives Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oherlin College Arcliives Roland M. Baumann, General Editor Roland M. Baumann, Jessica G. Broadwell, and Michael Morgenstem, compilers Gertrude F.Jacob Archival Publications Fimd Oberlin College Oberlin, Ohio 1996 Copyright ©1996 Oberlin College Printed on recycled and acid-free paper s Dedicated to William E. Bigglestone Oberlin College Archivist, 1966-1986 Oberlin College Campus ^ S^ 1989 Alphabetical Usting s/Camegie Building 52 KettoiiKHaU 49 AUm Memorial Alt Museum 56 King Bimding 22 AUencraft (Russian House) S LM3 (Afrikan Heritage House) 9 Afboretum 1 Malkny House _ 59 Asia House (Quadrant^e) 53 Memorial Arch 23 Athletic Relds 36 SedeyG.MuddCaitCT 30 Bailey House (Frendi House) 44 Noah HaU -

Library Oberlin College Libraries Perspectives

A Newsletter Spring 2017, Issue No. 56 of the Library Oberlin College Libraries Perspectives CHARLES LIVINGSTONE PAPERS conservatory library receives extensive DIGITIZED FOR LIVINGSTONE ONLINE blues collection THE LIBRARY ast summer the Conservatory Library recently digitized received an impressive collection of a letter and three Lblues-related audio recordings from personal journals Gordon Barrick “Barry” Neavill ’66 and handwritten Mary Ann Sheble. The collection comprises by Charles nearly 6,000 CDs and 4,000 LPs that Livingstone, provide extensive documentation of the Class of 1845 history of the blues. With reissues of the and brother of earliest blues recordings from the 1920s and renowned explorer extending up to the present, the collection is Dr. David Livingstone, for the Livingstone expansive in both chronological scope and Online archive (livingstoneonline.org). geographic range, an important element for Special Collections Librarian Ed Vermue a genre in which regional differences can became aware of the journals following a result in significantly distinct styles. Album cover. In 1966, Son House (1902- query from Justin Livingstone (Queen’s The donation greatly enhances 1988) performed in concert at Oberlin College, presenting two 45-minute sets of solo vocals University Belfast, no relation to the Oberlin’s blues holdings, which previously with guitar accompaniment. The recording was brothers Charles and David), who was numbered around 1,500 items. The released as a two-LP set in 1991 and is included in the Neavill gift (King Bee Records, KB-1001). preparing a scholarly edition of Missionary recordings will directly support teaching Travels, the travelogue from David and research in a number of conservatory be enhanced by a notable group of blues Livingstone’s journey.