Advancing High-Speed Rail Policy in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ron Degraw Transit Collection 2397

Ron Degraw Transit Collection 2397 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Ron Degraw Transit Collection 2397 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 SEPTA ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Harrisburg Line Capacity Improvements Upgrade of Track 2 from Glen Interlocking to Thorn Interlocking

HARRISBURG LINE CAPACITY IMPROVEMENTS UPGRADE OF TRACK 2 FROM GLEN INTERLOCKING TO THORN INTERLOCKING FEDERAL RAILROAD ADMINISTRATION FEDERAL-STATE PARTNERSHIP FOR STATE OF GOOD REPAIR PROGRAM GRANT APPLICATION Lead Applicant: Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) Joint Applicant: Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) FEDERAL FUNDING REQUESTED: $8,337,500 (50%) PROPOSED NON-FEDERAL MATCH: $8,337,500 (50%) TOTAL PROJECT COST: $16,675,000 PROJECT LOCATION: Caln Township, Downingtown Borough, East Caln Township, West Whiteland Township, & East Whiteland Township in Chester County, Pennsylvania - 6th Congressional District No Federal Grant Application Previously Submitted for this Project Table of Contents I. Project Summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Project Funding ..................................................................................................................................... 2 III. Applicant Eligibility ............................................................................................................................... 3 IV. NEC Project Eligibility ........................................................................................................................... 3 V. Detailed Project Description ................................................................................................................ 5 VI. Project Location ................................................................................................................................. -

Published by the Friends of Philadelphia Trolleys, Inc. Volume 11, Number 2 Spring 2017

Published by the Friends of Philadelphia Trolleys, Inc. Volume 11, Number 2 Spring 2017 By Harry Donahue Photos by Harry Donahue and Bill Monaghan ver the past winter, the Friends of Philadelphia Trolleys awarded grants to O trolleys in four different museums. Continuing our current effort to raise funding, a grant of $1,000.00 was given for ex-PTC Brill car Square Rail Museum on West Chester Pike in #8042 at the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum. The grant is being delayed by FPT until the late Newtown Square. Although Car #23 will be a summer. At this time, the annual Washington static display and not actually operate, FPT County Matching Grant program will made an exception in the case in giving this commences, thus allowing the grant amount to grant because another $500.00 grant was given be matched. If you would like to help increase the amount of the grant, please use the attached donation form for 8042. Help to get this wonderful old Brill Peter Witt car back in service at PTM. A grant of $500.00 was awarded on behalf of Red Arrow “St. Louie” #23 now at the Newtown to Brilliner #8 now at Shore Line Trolley Museum (Branford, Connecticut). There are several Red Arrow cars at Branford, but #8 is probably closest to operating condition. And finally, another $500.00 was awarded to the seat renewal project for Philadelphia Transportation Company’s PCC #2743 at the Rockhill Trolley Museum. All the refurbished seats have been returned to the car and are awaiting installation. This last grant will help pay the final bills on the project. -

Signalling on the High-Speed Railway Amsterdam–Antwerp

Computers in Railways XI 243 Towards interoperability on Northwest European railway corridors: signalling on the high-speed railway Amsterdam–Antwerp J. H. Baggen, J. M. Vleugel & J. A. A. M. Stoop Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands Abstract The high-speed railway Amsterdam (The Netherlands)–Antwerp (Belgium) is nearly completed. As part of a TEN-T priority project it will connect to major metropolitan areas in Northwest Europe. In many (European) countries, high-speed railways have been built. So, at first sight, the development of this particular high-speed railway should be relatively straightforward. But the situation seems to be more complicated. To run international services full interoperability is required. However, there turned out to be compatibility problems that are mainly caused by the way decision making has taken place, in particular with respect to the choice and implementation of ERTMS, the new European railway signalling system. In this paper major technical and institutional choices, as well as the choice of system borders that have all been made by decision makers involved in the development of the high-speed railway Amsterdam–Antwerp, will be analyzed. This will make it possible to draw some lessons that might be used for future railway projects in Europe and other parts of the world. Keywords: high-speed railway, interoperability, signalling, metropolitan areas. 1 Introduction Two major new railway projects were initiated in the past decade in The Netherlands, the Betuweroute dedicated freight railway between Rotterdam seaport and the Dutch-German border and the high-speed railway between Amsterdam Airport Schiphol and the Dutch-Belgian border to Antwerp (Belgium). -

Robustness of Railway Rolling Stock Speed Calculation Using Ground Vibration Measurements

Heriot-Watt University Research Gateway Robustness of railway rolling stock speed calculation using ground vibration measurements Citation for published version: Kouroussis, G, Connolly, D, Laghrouche, O, Forde, MC, Woodward, PK & Verlinden, O 2015, 'Robustness of railway rolling stock speed calculation using ground vibration measurements', MATEC Web of Conferences, vol. 20, 07002. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/20152007002 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1051/matecconf/20152007002 Link: Link to publication record in Heriot-Watt Research Portal Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: MATEC Web of Conferences Publisher Rights Statement: Open access General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via Heriot-Watt Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy Heriot-Watt University has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the content in Heriot-Watt Research Portal complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 MATEC Web of Conferences 20, 07002 (2015) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/20152007002 c Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2015 Robustness of railway rolling stock speed calculation using ground vibration measurements Georges Kouroussis1,a, David P. Connolly2,b, Omar Laghrouche2,c, Mike C. Forde3,d, Peter Woodward2,e and Olivier Verlinden1,f 1 University of Mons, Department of Theoretical Mechanics, Dynamics and Vibrations, 31 Boulevard Dolez, 7000 Mons, Belgium 2 Heriot-Watt University, Institute for Infrastructure & Environment, Edinburgh EH14 4AS, UK 3 University of Edinburgh, Institute for Infrastructure and Environment, Alexander Graham Bell Building, Edinburgh EH9 3JF, UK Abstract. -

Railway Station Liège-Guillemins

Reference report Railway station Liège-Guillemins A shining example of a European transport hub in the Wallonia region Designing clean entrances Liège-Guillemins: Liège‘s high-speed railway station The most important railway station in the Belgian city of Liège and in Fresh momentum for the city the Wallonia region as a whole, Liège-Guillemins was erected in Sep- This image of communication and transparency stands in sharp con- tember 2009 on the basis of designs by Santiago Calatrava. It is a stop- trast to the structure that preceded it. The old railway station, a 1958 ping point for Thalys and Intercity-Express trains, making the station a building that had fallen into disrepair, attempted to exert a sense of hub within the European high-speed network that runs between Lon- control over the growing numbers of railway services it saw – but the don, Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam and Cologne/Frankfurt: the distance glass and steel work of art that replaces it exudes light and radiance between Cologne and Liège can now be covered in just under an hour. and has given fresh momentum to Belgium‘s third-largest city. Oth- A good 500 trains per day are accommodated by this through station, er projects involving the station are being planned and the recently whose monumental canopy transforms it into a real landmark. opened Médiacité shopping and media centre, designed by Ron Arad, has created another new highlight. The futuristic station complex has Guiding principles: Communication and transparency a pivotal role to play in all these developments. The steel and glass roof – at once powerful and delicate – hangs above the platform like a colossal wave and flows into the oscillating roof Daylight on every level that reaches up to 50 metres over the 33,000-square metre main hall. -

Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States

Parsons Brinckerhoff 2010 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Monograph 26 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States Fellow: Francis P. Banko Professional Associate Principal Project Manager Lead Investigator: Jackson H. Xue Rail Vehicle Engineer December 2012 136763_Cover.indd 1 3/22/13 7:38 AM 136763_Cover.indd 1 3/22/13 7:38 AM Parsons Brinckerhoff 2010 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Monograph 26 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the United States Fellow: Francis P. Banko Professional Associate Principal Project Manager Lead Investigator: Jackson H. Xue Rail Vehicle Engineer December 2012 First Printing 2013 Copyright © 2013, Parsons Brinckerhoff Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, mechanical (including photocopying), recording, taping, or information or retrieval systems—without permission of the pub- lisher. Published by: Parsons Brinckerhoff Group Inc. One Penn Plaza New York, New York 10119 Graphics Database: V212 CONTENTS FOREWORD XV PREFACE XVII PART 1: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE RESEARCH 3 1.1 Unprecedented Support for High Speed Rail in the U.S. ....................3 1.2 Pioneering the Application of High Speed Rail Express Trainsets in the U.S. .....4 1.3 Research Objectives . 6 1.4 William Barclay Parsons Fellowship Participants ...........................6 1.5 Host Manufacturers and Operators......................................7 1.6 A Snapshot in Time .................................................10 CHAPTER 2 HOST MANUFACTURERS AND OPERATORS, THEIR PRODUCTS AND SERVICES 11 2.1 Overview . 11 2.2 Introduction to Host HSR Manufacturers . 11 2.3 Introduction to Host HSR Operators and Regulatory Agencies . -

High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning Urban and Regional Planning January 2007 High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2 Allison deCerreno Shishir Mathur San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/urban_plan_pub Part of the Infrastructure Commons, Public Economics Commons, Public Policy Commons, Real Estate Commons, Transportation Commons, Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons, Urban Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Allison deCerreno and Shishir Mathur. "High-Speed Rail Projects in the United States: Identifying the Elements of Success Part 2" Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning (2007). This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Urban and Regional Planning at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Urban and Regional Planning by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MTI Report 06-03 MTI HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS-PART 2 IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS-PART HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: Funded by U.S. Department of HIGH-SPEED RAIL Transportation and California Department PROJECTS IN THE UNITED of Transportation STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS PART 2 Report 06-03 Mineta Transportation November Institute Created by 2006 Congress in 1991 MTI REPORT 06-03 HIGH-SPEED RAIL PROJECTS IN THE UNITED STATES: IDENTIFYING THE ELEMENTS OF SUCCESS PART 2 November 2006 Allison L. -

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation

Interaction of Lifecycle Properties in High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi M.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2011 B.E., Aeronautics and Astronautics, University of Tokyo, 2009 Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2016 © 2016 Tatsuya Doi. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________________ Institute for Data, Systems, and Society May 6, 2016 Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Joseph M. Sussman JR East Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Certified by: __________________________________________________________________________ Olivier L. de Weck Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: _________________________________________________________________________ John N. Tsitsiklis Clarence J. Lebel Professor of Electrical Engineering IDSS Graduate Officer 1 2 Interaction of Lifecycle Properties In High Speed Rail Systems Operation by Tatsuya Doi Submitted to the Institute for Data, Systems, and Society on May 6, 2016 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering Systems ABSTRACT High-Speed Rail (HSR) has been expanding throughout the world, providing various nations with alternative solutions for the infrastructure design of intercity passenger travel. HSR is a capital-intensive infrastructure, in which multiple subsystems are closely integrated. Also, HSR operation lasts for a long period, and its performance indicators are continuously altered by incremental updates. -

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo-Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report – Discussion Draft 2 1

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo- Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report DISCUSSION DRAFT (Quantified Model Data Subject to Refinement) Table of Contents 1. Project Background: ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Early Study Efforts and Initial Findings: ................................................................................................ 5 3. Background Data Collection Interviews: ................................................................................................ 6 4. Fixed-Facility Capital Cost Estimate Range Based on Existing Studies: ............................................... 7 5. Selection of Single Route for Refined Analysis and Potential “Proxy” for Other Routes: ................ 9 6. Legal Opinion on Relevant Amtrak Enabling Legislation: ................................................................... 10 7. Sample “Timetable-Format” Schedules of Four Frequency New York-Chicago Service: .............. 12 8. Order-of-Magnitude Capital Cost Estimates for Platform-Related Improvements: ............................ 14 9. Ballpark Station-by-Station Ridership Estimates: ................................................................................... 16 10. Scoping-Level Four Frequency Operating Cost and Revenue Model: .................................................. 18 11. Study Findings and Conclusions: ......................................................................................................... -

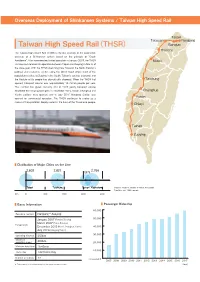

Overseas Deployment of Shinkansen Systems / Taiwan High Speed Rail

Overseas Deployment of Shinkansen Systems / Taiwan High Speed Rail Taipei Taoyuan Nangang Taiwan High Speed Rail( THSR) Banqiao Hsinchu The Taiwan High Speed Rail (THSR) is the first example of the exportation overseas of a Shinkansen system based on the principle of “Crash Avoidance”. After commencing limited operation in January 2007, the THSR Miaoli commenced commercial operation between Taipei and Zuoying in March of the same year. With the THSR stretching from Taipei in the North, Taiwan’s political and economic center, along the West Coast where most of the population resides, to Zuoying in the South, Taiwan’s society, economy, and the lifestyle of its people has dramatically changed. When the THSR first Taichung opened, transport volume was approximately 15 million people per year. This number has grown annually and in 2017 yearly transport volume exceeded 60 million passengers. In December 2015, Miaoli, Changhua and Changhua Yunlin stations were opened, and in July 2016 Nangang Station was Yunlin opened for commercial operation. The THSR continues to evolve as a means of transportation deeply rooted in the lives of the Taiwanese people. Chiayi Tainan Zuoying ■ Distribution of Major Cities on the Line 2,602 2,821 2,766 1,875 Taipei Taichung Tainan Kaohsiung Statistics Yearbook, Ministry of Interior, ROC(2020) Population unit: 1,000’s people km 0 100 200 300 400 ■ Basic Information ■ Passenger Ridership 60,000 Operating segment Nangang-Zuoying 50,000 January 2007 (Banqiao-Zuoying) March 2007 (Taipei-Banqiao) Inauguration December 2015 (Miaoli, Changhua, Yunlin) 40,000 July 2016 (Nangang-Taipei) 30,000 Operating distance 350km Maximum 300km operating speed 20,000 Minimum travel time 1h 45min 10,000 Trains/day 142 trains/day Number of stations 12 (Thousand)0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 20 13 2014 2015 2016 2017 ※ Train number is calculated based on the annual number of trains. -

Empire Corridor

U.S. System Summary: EMPIRE CORRIDOR Empire Corridor High-Speed Rail System (Source: NYSDOT) The Empire Corridor high-speed rail system is an es- rently in the Planning/Environmental stage with a vision tablished high-speed rail system containing 463 miles of to implement higher train speeds throughout the corridor. routes in two segments wholly contained within the State The entire route is part of the federally-designated Em- of New York, connecting New York City, Albany, Syra- pire Corridor High-Speed Rail Corridor. Operational and cuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls. High-speed proposed high-speed rail service in the Empire Corridor intercity passenger rail service is currently Operational in high-speed rail system is based primarily on incremen- small portions of each segment, with maximum speeds up tal improvements to existing railroad rights-of-way, with to 110 mph. The entire 463-mile Empire Corridor is cur- maximum train speeds up to 125 mph being considered. U.S. HIGH-SPEED RAIL SYSTEM SUMMARY: EMPIRE CORRIDOR | 1 SY STEM DESCRIPTION AND HISTORY System Description The Empire Corridor high-speed rail system consists of two segments, as summarized below. Empire Corridor High-Speed Rail System Segment Characteristics Segment Description Distance Segment Status Designated Corridor? Segment Population New York City, NY, to Albany, NY 141 Miles Operational Yes 13,362,857 Albany, NY, to Niagara Falls, NY 322 Miles Planning/Environmental Yes 4,072,741 The New York City, NY, to Albany, NY, segment is 141 Transportation Study, which determined that new tech- miles in length and includes major communities such as nology over a new dedicated right-of-way would be neces- Poughkeepsie and Rhinecliff-Kingston along the route.