Inside Libya Inside Libya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haftar's Calculus for Libya: What Happened, and What Is Next? ICSR Insight by Inga Kristina Trauthig

Haftar's Calculus for Libya: What Happened, and What is Next? ICSR Insight by Inga Kristina Trauthig In recent days, a battle for Tripoli has At the time of writing, fighting is been raging that bears the forlorn ongoing. On Sunday, 8 April, Tripoli’s possibility of regression for Libya as a only functioning civilian airport at Mitiga whole. A military offensive led by was forced to be evacuated as it was General Khalifa Haftar, commander of hit with air strikes attributed to the LNA. the so-called “Libyan National Army” These airstrikes took place the same (LNA) that mostly controls eastern day that the “Tripoli International Fair” Libya, was launched on April 3, to the occurred, signalling the formidable level dismay of much the international of resilience Libyans have attained after community. A few days after the launch eight years of turbulence following of the military campaign by Haftar, Qaddafi’s overthrow. some analysts have already concluded that “Libya is (…) [in] its third civil war since 2011”. The LNA forces first took the town of Gharyan, 100 km south of Tripoli, before advancing to the city’s outskirts. ICSR, Department of War Studies, King’s College London. All rights reserved. Haftar's Calculus for Libya: What Happened, and What is Next? ICSR Insight by Inga Kristina Trauthig What is happening? Haftar had been building his forces in central Libya for months. At the beginning of the year, he claimed to have “taken control” of southern Libya, indicating that he was prepping for an advance on the western part of Libya, the last piece missing. -

The Crisis in Libya

APRIL 2011 ISSUE BRIEF # 28 THE CRISIS IN LIBYA Ajish P Joy Introduction Libya, in the throes of a civil war, now represents the ugly facet of the much-hyped Arab Spring. The country, located in North Africa, shares its borders with the two leading Arab-Spring states, Egypt and Tunisia, along with Sudan, Tunisia, Chad, Niger and Algeria. It is also not too far from Europe. Italy lies to its north just across the Mediterranean. With an area of 1.8 million sq km, Libya is the fourth largest country in Africa, yet its population is only about 6.4 million, one of the lowest in the continent. Libya has nearly 42 billion barrels of oil in proven reserves, the ninth largest in the world. With a reasonably good per capita income of $14000, Libya also has the highest HDI (Human Development Index) in the African continent. However, Libya’s unemployment rate is high at 30 percent, taking some sheen off its economic credentials. Libya, a Roman colony for several centuries, was conquered by the Arab forces in AD 647 during the Caliphate of Utman bin Affan. Following this, Libya was ruled by the Abbasids and the Shite Fatimids till the Ottoman Empire asserted its control in 1551. Ottoman rule lasted for nearly four centuries ending with the Ottoman defeat in the Italian-Ottoman war. Consequently, Italy assumed control of Libya under the Treaty of 1 Lausanne (1912). The Italians ruled till their defeat in the Second World War. The Libyan constitution was enacted in 1949 and two years later under Mohammed Idris (who declared himself as Libya’s first King), Libya became an independent state. -

Russian Snipers, Missiles and Warplanes Try to Tilt Libyan War - the New York Times

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 11/12/2019 2:59:54 PM 11/12/2019 Russian Snipers, Missiles and Warplanes Try to Tilt Libyan War - The New York Times Sljc iXcUt Jlork (Limes Russian Snipers, Missiles and Warplanes Try to Tilt Libyan War Moscow is plunging deeper into a war of armed drones in a strategic hot spot rich with oil, teeming with migrants and riddled with militants. By David D. Kirkpatrick ^ i» Published Nov. 5, 2019 Updated Nov. 7, 2019 TRIPOLI, Libya — The casualties at the Aziziya field hospital south of Tripoli used to arrive with gaping wounds and shattered limbs, victims of the haphazard artillery fire that has defined battles among Libyan militias. But now medics say they are seeing something new: narrow holes in a head or a torso left by bullets that kill instantly and never exit the body. It is the work, Libyan fighters say, of Russian mercenaries, including skilled snipers. The lack of an exit wound is a signature of the ammunition used by the same Russian mercenaries elsewhere. The snipers are among about 200 Russian fighters who have arrived in Libya in the last six weeks, part of a broad campaign by the Kremlin to reassert its influence across the Middle East and Africa. After four years of behind-the-scenes financial and tactical support for a would-be Libyan strongman, Russia is now pushing far more directly to shape the outcome of Libya’s messy civil war. It has introduced advanced Sukhoi jets, coordinated missile strikes, and precision-guided artillery, as well as the snipers — the same playbook that made Moscow a kingmaker in the Syrian civil war. -

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1

Libyan Municipal Council Research 1. Detailed Methodology 2. Participation 3. Awareness 4. Knowledge 5. Communication 6. Service Delivery 7. Legitimacy 8. Drivers of Legitimacy 9. Focus Group Recommendations 10. Demographics Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research by Altai Consulting. This research is intended to support the development and evaluation of IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative programming with municipal councils. The research consisted of quantitative and qualitative components, conducted by IRI and USAID/OTI Libya Transition Initiative respectively. • Data was collected April 14 to May 24, 2016, and was conducted over the phone from Altai’s call center using computer-assisted telephone technology. • The sample was 2,671 Libyans aged 18 and over. • Quantitative: Libyans from the 22 administrative districts were interviewed on a 45-question questionnaire on municipal councils. In addition, 13 municipalities were oversampled to provide a more focused analysis on municipalities targeted by programming. Oversampled municipalities include: Tripoli Center (224), Souq al Jumaa (229), Tajoura (232), Abu Salim (232), Misrata (157), Sabratha (153), Benghazi (150), Bayda (101), Sabha (152), Ubari (102), Weddan (101), Gharyan (100) and Shahat (103). • The sample was post-weighted in order to ensure that each district corresponds to the latest population pyramid available on Libya (US Census Bureau Data, updated 2016) in order for the sample to be nationally representative. • Qualitative: 18 focus groups were conducted with 5-10 people of mixed employment status and level of education in Tripoli Center (men and women), Souq al Jumaa (men and women), Tajoura (men), Abu Salim (men), Misrata (men and women), Sabratha (men and women), Benghazi (men and women), Bayda (men), Sabha (men and women), Ubari (men), and Shahat (men). -

Libya's Conflict

LIBYA’S BRIEF / 12 CONFLICT Nov 2019 A very short introduction SERIES by Wolfgang Pusztai Freelance security and policy analyst * INTRODUCTION Eight years after the revolution, Libya is in the mid- dle of a civil war. For more than four years, inter- national conflict resolution efforts have centred on the UN-sponsored Libya Political Agreement (LPA) process,1 unfortunately without achieving any break- through. In fact, the situation has even deteriorated Summary since the onset of Marshal Haftar’s attack on Tripoli on 4 April 2019.2 › Libya is a failed state in the middle of a civil war and increasingly poses a threat to the An unstable Libya has wide-ranging impacts: as a safe whole region. haven for terrorists, it endangers its north African neighbours, as well as the wider Sahara region. But ter- › The UN-facilitated stabilisation process was rorists originating from or trained in Libya are also a unsuccessful because it ignored key political threat to Europe, also through the radicalisation of the actors and conflict aspects on the ground. Libyan expatriate community (such as the Manchester › While partially responsible, international Arena bombing in 2017).3 Furthermore, it is one of the interference cannot be entirely blamed for most important transit countries for migrants on their this failure. way to Europe. Through its vast oil wealth, Libya is also of significant economic relevance for its neigh- › Stabilisation efforts should follow a decen- bours and several European countries. tralised process based on the country’s for- mer constitution. This Conflict Series Brief focuses on the driving factors › Wherever there is a basic level of stability, of conflict dynamics in Libya and on the shortcomings fostering local security (including the crea- of the LPA in addressing them. -

Gaddafi Supporters Since 2011

Country Policy and Information Note Libya: Actual or perceived supporters of former President Gaddafi Version 3.0 April 2019 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

After Gaddafi 01 0 0.Pdf

Benghazi in an individual capacity and the group it- ures such as Zahi Mogherbi and Amal al-Obeidi. They self does not seem to be reforming. Al-Qaeda in the found an echo in the administrative elites, which, al- Islamic Maghreb has also been cited as a potential though they may have served the regime for years, spoiler in Libya. In fact, an early attempt to infiltrate did not necessarily accept its values or projects. Both the country was foiled and since then the group has groups represent an essential resource for the future, been taking arms and weapons out of Libya instead. and will certainly take part in a future government. It is unlikely to play any role at all. Scenarios for the future The position of the Union of Free Officers is unknown and, although they may form a pressure group, their membership is elderly and many of them – such as the Three scenarios have been proposed for Libya in the rijal al-khima (‘the men of the tent’ – Colonel Gaddafi’s future: (1) the Gaddafi regime is restored to power; closest confidants) – too compromised by their as- (2) Libya becomes a failing state; and (3) some kind sociation with the Gaddafi regime. The exiled groups of pluralistic government emerges in a reunified state. will undoubtedly seek roles in any new regime but The possibility that Libya remains, as at present, a they suffer from the fact that they have been abroad divided state between East and West has been ex- for up to thirty years or more. -

Libya Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and Libya Conflict recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Libya achieved independence from United Nations (UN) trusteeship in 1951 Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) as an amalgamation of three former Ottoman provinces, Tripolitania, Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Cyrenaica and Fezzan under the rule of King Mohammed Idris. In 1969, King Idris was deposed in a coup staged by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. He promptly abolished the monarchy, revoked the constitution, and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, established the Libya Arab Republic. By 1977, the Republic was transformed Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. into the leftist-leaning Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya pursued a “deviant foreign policy”, epitomized February 2018 | Vol. 1 by its radical belligerence towards the West and its endorsement of anti- imperialism. In the late 1990s, Libya began to re-normalize its relations with the West, a development that gradually led to its rehabilitation from the CONTENTS status of a pariah, or a “rogue state.” As part of its rapprochement with the Situation analysis 1 West, Libya abandoned its nuclear weapons programme in 2003, resulting Causes of the conflict 2 in the lifting of UN sanctions. -

Libya Idp and Returnee Report

MAR APR DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX 2020 dtm.iom.int/libya [email protected] LIBYA IDP AND RETURNEE REPORT MOBILITY TRACKING ROUND 30 MARCH - APRIL 2020 Project funded by the European Union © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Cover Photo: IOM collecting household information from an IDP head of household in Surman, Libya, as part of assistance provided via interagency Rapid Response Mechanism; February 2020 ©IOM 2020 / Majdi El Nakua Note: Lack of use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is appropriate to context as the photo was taken before Covid-19 cases were reported in Libya, and therefore before public health advisory on use of PPE. JAN FEB LIBYA IDP AND RETURNEE REPORT 20202019 Contents Key findings (Round 30) ................................................................................................4 Overview .....................................................................................................................................5 Update on Conflict in Western Libya .................................................................6 Areas of Displacement and Return .......................................................................7 Locations of Displacement and Return Map .................................................9 -

Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2256 Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War by Andrew Engel May 20, 2014 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Andrew Engel Andrew Engel, a former research assistant at The Washington Institute, recently received his master's degree in security studies at Georgetown University and currently works as an Africa analyst. Brief Analysis Long-simmering tensions between non-Islamist and Islamist forces have boiled over into military actions centered around Benghazi and Tripoli, entrenching the country's rival alliances and bringing them ever closer to civil war. n May 16, former Libyan army general Khalifa Haftar launched "Operation Dignity of Libya" in Benghazi, O aiming to "c leanse the city of terrorists." The move came three months after he announced the overthrow of the government but failed to act on his proclamation. Since Friday, however, army units loyal to Haftar have actively defied armed forces chief of staff Maj. Gen. Salem al-Obeidi, who called the operation "a coup." And on Monday, sympathetic forces based in Zintan extended the operation to Tripoli. These and other developments are edging the country closer to civil war, complicating U.S. efforts to stabilize post-Qadhafi Libya. DIVIDING LINES I slamists and non-Islamist forces have long been contesting each other's claims to being the legitimate heart of the 2011 revolution. Islamist factions such as the Muslim Brotherhood-related Justice and Construction Party and the Loyalty to the Martyrs Bloc have dominated the General National Congress (GNC) since summer 2013, when the forcibly passed Political Isolation Law effectively barred all former Qadhafi regime members -- even those who had fought the regime -- from participating in government for ten years. -

For Ubari LBY2007 Libya

Research Terms of Reference Area-Based Assessment (ABA) for Ubari LBY2007 Libya 22nd of January, 2021 V3 1. Executive Summary Country of intervention Libya Type of Emergency □ Natural disaster X Conflict Type of Crisis □ Sudden onset □ Slow onset X Protracted Mandating Body/ EUTF Agency Project Code 14EHG Overall Research Timeframe (from 01/10/2020 to 14/04/2021 research design to final outputs / M&E) Research Timeframe 1. Start collect data: 26/01/2021 5. Preliminary presentation: 13/03/2021 Add planned deadlines 2. Data collected: 25/02/2021 6. Outputs sent for validation: 31/03/2021 (for first cycle if more 3. Data analysed: 05/03/2021 7. Outputs published: 14/04/2021 than 1) 4. Data sent for validation: 31/03/2021 8. Final presentation: 14/04/2021 Number of X Single assessment (one cycle) assessments □ Multi assessment (more than one cycle) [Describe here the frequency of the cycle] Humanitarian Milestone Deadline milestones □ Donor plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ Specify what will the □ Inter-cluster plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ assessment inform and □ Cluster plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ when e.g. The shelter cluster □ NGO platform plan/strategy _ _/_ _/_ _ _ _ will use this data to X Other (Specify): 31/03/2021 The Area-Based Assessment draft its Revised Flash (ABA) for Ubari will directly inform ACTED Appeal; protection activities in Ubari. (See rationale) Audience Type & Audience type Dissemination Dissemination Specify X Strategic X General Product Mailing (e.g. -

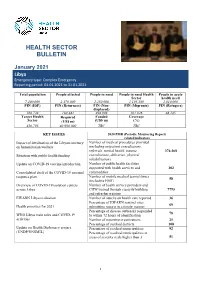

January 2021 Libya Emergency Type: Complex Emergency Reporting Period: 01.01.2021 to 31.01.2021

HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN January 2021 Libya Emergency type: Complex Emergency Reporting period: 01.01.2021 to 31.01.2021 Total population People affected People in need People in need Health People in acute Sector health need 7,400,000 2,470,000 1,250,000 1,195,389 1,010,000 PIN (IDP) PIN (Returnees) PIN (Non- PIN (Migrants) PIN (Refugees) displaced) 168,728 180,482 498,908 301,026 46,245 Target Health Required Funded Coverage Sector (US$ m) (US$ m) (%) 450,795 40,990,000 TBC TBC KEY ISSUES 2020 PMR (Periodic Monitoring Report) related indicators Impact of devaluation of the Libyan currency Number of medical procedures provided on humanitarian workers (including outpatient consultations, referrals, mental health, trauma 376.468 Situation with public health funding consultations, deliveries, physical rehabilitation) Update on COVID-19 vaccine introduction Number of public health facilities supported with health services and 302 Consolidated draft of the COVID-19 national commodities response plan. Number of mobile medical teams/clinics 58 (including EMT) Overview of COVID-19 isolation centers Number of health service providers and across Libya CHW trained through capacity building 7793 and refresher training EWARN Libya evaluation Number of attacks on health care reported 36 Percentage of EWARN sentinel sites 68 Health priorities for 2021 submitting reports in a timely manner Percentage of disease outbreaks responded 78 WHO Libya main roles and COVID-19 to within 72 hours of identification activities Number of reporting organizations 25 Percentage of reached districts 100 Update on Health Diplomacy project Percentage of reached municipalities 92 (UNDP/UNSMIL) Percentage of reached municipalities in areas of severity scale higher than 3 51 1 HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN January 2021 SITUATION OVERVIEW • The UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called on foreign fighters and mercenaries in Libya to immediately leave because "the Libyans have already proven that, left alone, they are able to address their problems".