A Comparative Study of the Penitential Poem Adon Haselihot, Sung in the Babylonian- Jewish Tradition in Four Communities *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIA RELEASE for Immediate Release CELEBRATING OUR

MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release CELEBRATING OUR RACIAL AND RELIGIOUS HARMONY WITH NEW GUIDED WALKS BY THE NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD The Singapore Town Plan, showing Queen, Waterloo and Bencoolen Streets to be part of a “European Town”, late-19th century. Despite being originally designated as a European quarter, significant numbers of Eurasians, Chinese, Indians, Jews, Malays, amongst other communities, also settled in the area. Image courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board Singapore, 14 November 2019 – Along Waterloo Street, a devotee from the Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple walks two doors down to the neighbouring Sri Krishnan Temple to offer prayers. This is a common sight in the area, where temples, churches, a mosque and a synagogue are all within a stone’s throw of one another. These houses of worship stand as testaments to the diverse communities who lived, worked and played side by side around Queen, Waterloo and Bencoolen Streets in Singapore’s Bras Basah.Bugis precinct, exemplifying the values of understanding and openness that have allowed them to exist and thrive together. 2 With the launch of a new programme titled Harmony Walks by the National Heritage Board (NHB), Singaporeans will be able to embark on free guided walks along Queen, Waterloo and Bencoolen Streets and learn more about the commonalities shared by diverse communities in the areas of religion, culture and built heritage. Harmony Walks comprises three guided walks that will cover the following designated areas: • Harmony Walks: Queen, Waterloo and Bencoolen Streets • Harmony Walks: Telok Ayer (To be launched in 2020) • Harmony Walks: South Bridge Road (To be launched in 2020) 3 The first of the three walks is Harmony Walks: Queen, Waterloo and Bencoolen Streets, which covers a total of seven religious institutions – Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple, Sri Krishnan Temple, Maghain Aboth Synagogue, Cathedral of the Good Shepherd, Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Kum Yan Methodist Church and Masjid Bencoolen. -

Singapore Terrorism Threat Assessment Report 2021

SINGAPORE TERRORISM THREAT ASSESSMENT REPORT 2021 2 3 OVERVIEW The terrorism threat to Singapore remains high. Global terrorist groups like the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Al-Qaeda (AQ) have proven resilient and adaptable, despite their leadership losses and setbacks in recent years. Amidst the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, they have stepped up their recruitment and propaganda efforts on social media, encouraging their supporters worldwide to conduct attacks. 2. The enduring appeal of ISIS violent ideology is seen among the self- radicalised cases dealt with in Singapore in the past two years, the majority of whom were ISIS supporters. While Islamist terrorism remains the key concern, other emergent threats such as far-right extremism can also potentially propel at- risk individuals towards violent radicalism. In December 2020, Singapore detected its first self-radicalised individual who was inspired by far-right extremist ideologies. 3. There is currently no specific and credible intelligence of an imminent terrorist attack against Singapore. However, since the last Report issued on 22 January 2019, the Internal Security Department (ISD) has averted terrorist attacks by two Singaporean youths targeting places of worship in Singapore. These cases underscore the very real threat of lone-actor attacks by self-radicalised individuals. EXTERNAL TERRORISM THREAT ISIS Continues to be Primary Threat 4. Despite losing its last territorial stronghold in March 2019, ISIS remains an active insurgent force in Syria and Iraq. It reportedly still has some 10,000 fighters in the conflict zone and tens of millions of dollars in cash reserves. Over the past year, ISIS has escalated its insurgent activities in the conflict zone, taking advantage of the security vacuum left by reduced military operations due to COVID-19 and the reduction in US troops in Iraq. -

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities 469190 789811 9 Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore

Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Inter-religious harmony is critical for Singapore’s liveability as a densely populated, multi-cultural city-state. In today’s STUDIES URBAN SYSTEMS world where there is increasing polarisation in issues of race and religion, Singapore is a good example of harmonious existence between diverse places of worship and religious practices. This has been achieved through careful planning, governance and multi-stakeholder efforts, and underpinned by principles such as having a culture of integrity and innovating systematically. Through archival research and interviews with urban pioneers and experts, Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities documents the planning and governance of religious harmony in Singapore from pre-independence till the present and Communities Practices Spaces, Religious Harmony in Singapore: day, with a focus on places of worship and religious practices. Religious Harmony “Singapore must treasure the racial and religious harmony that it enjoys…We worked long and hard to arrive here, and we must in Singapore: work even harder to preserve this peace for future generations.” Lee Hsien Loong, Prime Minister of Singapore. Spaces, Practices and Communities 9 789811 469190 Religious Harmony in Singapore: Spaces, Practices and Communities Urban Systems Studies Books Water: From Scarce Resource to National Asset Transport: Overcoming Constraints, Sustaining Mobility Industrial Infrastructure: Growing in Tandem with the Economy Sustainable Environment: -

The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy

Luke Howson University of Liverpool The Role of Ultra-Orthodox Political Parties in Israeli Democracy Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy By Luke Howson July 2014 Committee: Clive Jones, BA (Hons) MA, PhD Prof Jon Tonge, PhD 1 Luke Howson University of Liverpool © 2014 Luke Howson All Rights Reserved 2 Luke Howson University of Liverpool Abstract This thesis focuses on the role of ultra-orthodox party Shas within the Israeli state as a means to explore wider themes and divisions in Israeli society. Without underestimating the significance of security and conflict within the structure of the Israeli state, in this thesis the Arab–Jewish relationship is viewed as just one important cleavage within the Israeli state. Instead of focusing on this single cleavage, this thesis explores the complex structure of cleavages at the heart of the Israeli political system. It introduces the concept of a ‘cleavage pyramid’, whereby divisions are of different saliency to different groups. At the top of the pyramid is division between Arabs and Jews, but one rung down from this are the intra-Jewish divisions, be they religious, ethnic or political in nature. In the case of Shas, the religious and ethnic elements are the most salient. The secular–religious divide is a key fault line in Israel and one in which ultra-orthodox parties like Shas are at the forefront. They and their politically secular counterparts form a key division in Israel, and an exploration of Shas is an insightful means of exploring this division further, its history and causes, and how these groups interact politically. -

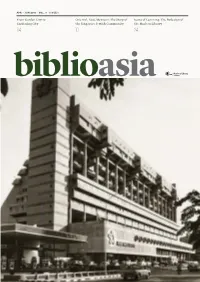

Apr–Jun 2013

VOL. 9 iSSUe 1 FEATURE APr – jUn 2013 · vOL. 9 · iSSUe 1 From Garden City to Oriental, Utai, Mexican: The Story of Icons of Learning: The Redesign of Gardening City the Singapore Jewish Community the Modern Library 04 10 24 01 BIBLIOASIA APR –JUN 2013 Director’s Column Editorial & Production “A Room of One’s Own”, Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay, argues for the place of women in Managing Editor: Stephanie Pee Editorial Support: Sharon Koh, the literary tradition. The title also makes for an apt underlying theme of this issue Masamah Ahmad, Francis Dorai of BiblioAsia, which explores finding one’s place and space in Singapore. Contributors: Benjamin Towell, With 5.3 million people living in an area of 710 square kilometres, intriguing Bernice Ang, Dan Koh, Joanna Tan, solutions in response to finding space can emerge from sheer necessity. This Juffri Supa’at, Justin Zhuang, Liyana Taha, issue, we celebrate the built environment: the skyscrapers, mosques, synagogues, Noorashikin binte Zulkifli, and of course, libraries, from which stories of dialogue, strife, ambition and Siti Hazariah Abu Bakar, Ten Leu-Jiun Design & Print: Relay Room, Times Printers tradition come through even as each community attempts to find a space of its own and leave a distinct mark on where it has been and hopes to thrive. Please direct all correspondence to: A sense of sanctuary comes to mind in the hubbub of an increasingly densely National Library Board populated city. In Justin Zhuang’s article, “From Garden City to Gardening City”, he 100 Victoria Street #14-01 explores the preservation and the development of the green lungs of Sungei Buloh, National Library Building Singapore 188064 Chek Jawa and, recently, the Rail Corridor, as breathing spaces of the city. -

President Trump Says Antisemitism Is 'Horrible' and 'Has to Stop'

ASHTON Opinion. Tradition. KUTCHER MCMASTER GOD’S RECOUNTS ON THE TALMUDIC HOLOCAUST NUDGE TALE A2. A9. A11. THE algemeiner JOURNAL $1.00 - PRINTED IN NEW YORK FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 24 , 2017 | 28 SHEVAT 5777 VOL. XLV NO. 2296 President Trump At Least Ten Jewish Community Says Antisemitism Centers Across Is ‘Horrible’ and US Targeted ‘Has to Stop’ BY BARNEY BREEN-PORTNOY At least ten Jewish community centers across America received telephone bomb threats on Monday, according to media reports. NBC News reported that JCCs in Birmingham, Cleve- land, Chicago, St. Paul, Tampa, Albuquerque, Houston, Milwaukee, Nashville and Buffalo were evacuated. No bombs were found at any of the threatened sites. This marked the fourth spate of concurrent bomb threats issued against JCCs in different parts of the US since the start of 2017. In a statement on Monday, Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan A. Greenblatt said, “We are confident that President Donald Trump. Photo: Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons. BY BARNEY BREEN against Jewish community centers “There is something going on Police tape outside the JCC in Nashville, Tenn., after a recent across the country and the that doesn’t allow it to fully heal,” telephone bomb threat. Photo: YouTube screenshot. -PORTNOY desecration of graves at a Jewish he stated. “Sometimes it gets better Antisemitism is “horrible” and cemetery in St. Louis. and then it busts apart. But we want JCCs around the country are taking the necessary security “has to stop,” US President Donald “The antisemitic threats to have it get very much better, get protections, and that law enforcement officials are making Trump said on Tuesday during targeting our Jewish commu- unified and stay together.” their investigation of these threats a high priority. -

EWISH Vo1ce HERALD

- ,- The 1EWISH Vo1CE HERALD /'f) ,~X{b1)1 {\ ~ SERVING RHODE ISLAND AND SOUTHEASTERN MASSACHUSETTS V C> :,I 18 Nisan 5773 March 29, 2013 Obama gains political capital President asserts that political leaders require a push BY RON KAMPEAS The question now is whether Obama has the means or the WASHINGTON (JTA) - For will to push the Palestinians a trip that U.S. officials had and Israelis back to the nego cautioned was not about get tiating table. ting "deliverables," President U.S. Secretary of State John Obama's apparent success Kerry, who stayed behind during his Middle East trip to follow up with Israeli at getting Israel and Turkey Prime Minister Benjamin to reconcile has raised some Netanyahu's team on what hopes for a breakthrough on happens next, made clear another front: Israeli-Pales tinian negotiations. GAINING I 32 Survivors' testimony Rick Recht 'rocks' in concert. New technology captures memories BY EDMON J. RODMAN In the offices of the Univer Rock star Rick Recht to perform sity of Southern California's LOS ANGELES (JTA) - In a Institute for Creative Technol dark glass building here, Ho ogies, Gutter - who, as a teen in free concert locaust survivor Pinchas Gut ager - had survived Majdanek, ter shows that his memory is Alliance hosts a Jewish rock star'for audiences ofall ages the German Nazi concentra cr ystal clear and his voice is tion camp on the outskirts of BY KARA MARZIALI Recht, who has been compared to James Taylor strong. His responses seem a Lublin, Poland, sounds and [email protected] for his soulfulness and folksy flavor and Bono for bit delayed - not that different looks very much alive. -

Between Mumbai and Manila

Manfred Hutter (ed.) Between Mumbai and Manila Judaism in Asia since the Founding of the State of Israel (Proceedings of the International Conference, held at the Department of Comparative Religion of the University of Bonn. May 30, to June 1, 2012) V&R unipress Bonn University Press Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. 296’.095’0904–dc23 ISBN 978-3-8471-0158-1 ISBN 978-3-8470-0158-4 (E-Book) Publications of Bonn University Press are published by V&R unipress GmbH. Copyright 2013 by V&R unipress GmbH, D-37079 Goettingen All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, microfilm and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printing and binding: CPI Buch Bu¨cher.de GmbH, Birkach Printed in Germany Contents Manfred Hutter / Ulrich Vollmer Introductory Notes: The Context of the Conference in the History of Jewish Studies in Bonn . ................... 7 Part 1: Jewish Communities in Asia Gabriele Shenar Bene Israel Transnational Spaces and the Aesthetics of Community Identity . ................................... 21 Edith Franke Searching for Traces of Judaism in Indonesia . ...... 39 Vera Leininger Jews in Singapore: Tradition and Transformation . ...... 53 Manfred Hutter The Tiny Jewish Communities in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia . 65 Alina Pa˘tru Judaism in the PR China and in Hong Kong Today: Its Presence and Perception . -

The Dynamics of Change in Jewish Oriental Ethnic Music in Israel Author(S): Amnon Shiloah and Erik Cohen Source: Ethnomusicology, Vol

Society for Ethnomusicology The Dynamics of Change in Jewish Oriental Ethnic Music in Israel Author(s): Amnon Shiloah and Erik Cohen Source: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 27, No. 2 (May, 1983), pp. 227-252 Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of Society for Ethnomusicology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/851076 Accessed: 19/04/2010 03:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=illinois. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for Ethnomusicology and University of Illinois Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethnomusicology. -

High Holy Days 5778

High Holy Days 5778 Tishre 5778 Fall 2017 Kahal Joseph Congregation Los Angeles California This Booklet is Dedicated in Memory of Anita Wozniak Hana bat Haviva, z’’l 1961-2017 May the community she loved so much shine through the pages in your hands. Table of Contents Dedication to Anita Wozniak .............................................. 2 Guide to Prayer Services .................................................... 4 Rabbi Raif Melhado’s Message .......................................... 6 President Yvette Dabby’s Message ................................... 7 A Letter from Ron Einy, Chairperson ................................ 9 A Letter from Michelle Kurtz, VP of Membership ............ 10 KJ Holiday Schedule Rosh Hashana ........................................................... 11 Yom Kippur ................................................................ 13 Sukkot ........................................................................ 14 Simhat Torah .............................................................. 16 Introducing our Clergy ..................................................... 18 What is Rosh Hashana? ................................................... 20 What is Yom Kippur? ........................................................ 22 History of Iraqi & Persian Jews ........................................ 24 History of Kahal Joseph ................................................... 26 Preserving Iraqi Heritage .................................................. 28 The Selihot Prayers in English Letters ........................... -

On Diversity and Identity Among Indian Jews by Prof. Shalva Weil

A course under MHRD scheme on Global Initiative on Academic Network (GIAN) On Diversity and Identity among Indian Jews by Prof. Shalva Weil Course Venue: Date: 23-31 January 2017 Time: 4:00-7:00 PM Overview The Jews of India represent a miniscule minority residing in harmony among Hindus, Muslims and Christians for generations. India is the only place in the world where Jews never suffered antisemitism, except during the Portuguese colonial period, as will be demonstrated in the course. The three major Jewish communities – the Bene Israel, the Cochin Jews, and the ‘Baghdadi’ Jews – retained their faith in monotheism in a polytheistic environment, whilst at the same time, being influenced by caste and religion in their daily practices. In the final analysis, Indian nationalism and global politics decided their fate. Today, most Indian Jews live in the state of Israel. However, their impact on Indian society was great, whether in the field of the arts, the military, commerce or in the free professions. The course throws new light on the diversity of India’s Jewish communities, spinning the unique narratives of each community. It includes in the discussion the temporary sojourn of 1 European Jews, who fled the Holocaust to India. In addition, it touches upon an increasing global phenomenon of weaving “Israelite” myths whereby the Shinlung of north-east India, today designated the “Bnei Menashe”, are migrating to Israel, and new Judaizing groups are emerging in India, such as the “Bene Ephraim” of Andhra Pradesh. The course provides a critical analysis of the position of the Jews in India both synchronically and diachronically. -

ISSUE 73 - AUTUMN 2000 Established 1971

JOURNAL OF BABYLONIAN JEWRY PUBLISHED BY THE EXILARCH’S FOUNDATION Now found on www.thescribe.uk.com ISSUE 73 - AUTUMN 2000 Established 1971 A Happy New Year 5761 to all our Readers and Friends The procession of His Royal Highness The Exilarch on his weekly visit to the Grand Caliph of Baghdad, ALMUSTANJID BILLAH, accompanied by Benjamin of Tudela (12th Century) who wrote in his diary that the Caliph knows all languages, and is well-versed in the law of Israel. He reads and writes the holy language (Hebrew) and is attended by many belonging to the people of Israel. He will not partake of anything unless he has earned it by the work of his own hands. The men of Islam see him once a year. In Baghdad there are about 40,000 Jews “dwelling in security, prosperity and honour and amongst them are great sages, the heads of Academies engaged in the study of the Law. At the head of them all is Daniel, The Exilarch, who traces his pedigree to King David. He has been invested with authority over all the Jews in the Abbassid Empire. Every Thursday he goes to pay a visit to the great Caliph and horsemen, Gentiles as well as Jews, escort him and heralds proclaim in advance, ‘Make way before our Lord, the son of David, as is due unto him’. On arrival the Caliph rises and puts him on a throne, opposite him, which the prophet Mohammed had ordered to be made for him. He granted him the seal of office and instructed his followers to salute him (the Exilarch) and that anyone who should refuse to rise up should receive one hundred stripes.” THOUGHTS & AFTERTHOUGHTS by Naim Dangoor REFLECTIONS ON T H E as martyrs for the free world and should that G-d cannot do wrong, they try to put HOLOCAUST be remembered and honoured throughout the blame on the victims themselves.