The Genomic Basis of Evolved Virus Resistance Is Dependent on Environmental Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A CRISPR-Cas9–Engineered Mouse Model for GPI-Anchor Deficiency Mirrors Human Phenotypes and Exhibits Hippocampal Synaptic Dysfunctions

A CRISPR-Cas9–engineered mouse model for GPI-anchor deficiency mirrors human phenotypes and exhibits hippocampal synaptic dysfunctions Miguel Rodríguez de los Santosa,b,c,d, Marion Rivalane,f, Friederike S. Davidd,g, Alexander Stumpfh, Julika Pitschi,j, Despina Tsortouktzidisi, Laura Moreno Velasquezh, Anne Voigth, Karl Schillingk, Daniele Matteil, Melissa Longe,f, Guido Vogta,c, Alexej Knausd, Björn Fischer-Zirnsaka,c, Lars Wittlerm, Bernd Timmermannn, Peter N. Robinsono,p, Denise Horna, Stefan Mundlosa,c, Uwe Kornaka,c,q, Albert J. Beckeri, Dietmar Schmitzh, York Wintere,f, and Peter M. Krawitzd,1 aInstitute for Medical Genetics and Human Genetics, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 13353 Berlin, Germany; bBerlin-Brandenburg School for Regenerative Therapies, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 13353 Berlin, Germany; cResearch Group Development and Disease, Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, 14195 Berlin, Germany; dInstitute for Genomic Statistics and Bioinformatics, University of Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany; eAnimal Outcome Core Facility of the NeuroCure Center, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 10117 Berlin, Germany; fInstitute of Cognitive Neurobiology, Humboldt University, 10117 Berlin, Germany; gInstitute of Human Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, University Hospital Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany; hNeuroscience Research Center, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 10117 Berlin, Germany; iSection for Translational Epilepsy Research, Department of Neuropathology, University Hospital Bonn, 53127 Bonn, Germany; jDepartment of Epileptology, -

Cldn19 Clic2 Clmp Cln3

NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation When time to diagnosis matters, the NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation from Athena Diagnostics delivers rapid, 5- to 7-day results on a targeted 1,722-genes. A2ML1 ALAD ATM CAV1 CLDN19 CTNS DOCK7 ETFB FOXC2 GLUL HOXC13 JAK3 AAAS ALAS2 ATP1A2 CBL CLIC2 CTRC DOCK8 ETFDH FOXE1 GLYCTK HOXD13 JUP AARS2 ALDH18A1 ATP1A3 CBS CLMP CTSA DOK7 ETHE1 FOXE3 GM2A HPD KANK1 AASS ALDH1A2 ATP2B3 CC2D2A CLN3 CTSD DOLK EVC FOXF1 GMPPA HPGD K ANSL1 ABAT ALDH3A2 ATP5A1 CCDC103 CLN5 CTSK DPAGT1 EVC2 FOXG1 GMPPB HPRT1 KAT6B ABCA12 ALDH4A1 ATP5E CCDC114 CLN6 CUBN DPM1 EXOC4 FOXH1 GNA11 HPSE2 KCNA2 ABCA3 ALDH5A1 ATP6AP2 CCDC151 CLN8 CUL4B DPM2 EXOSC3 FOXI1 GNAI3 HRAS KCNB1 ABCA4 ALDH7A1 ATP6V0A2 CCDC22 CLP1 CUL7 DPM3 EXPH5 FOXL2 GNAO1 HSD17B10 KCND2 ABCB11 ALDOA ATP6V1B1 CCDC39 CLPB CXCR4 DPP6 EYA1 FOXP1 GNAS HSD17B4 KCNE1 ABCB4 ALDOB ATP7A CCDC40 CLPP CYB5R3 DPYD EZH2 FOXP2 GNE HSD3B2 KCNE2 ABCB6 ALG1 ATP8A2 CCDC65 CNNM2 CYC1 DPYS F10 FOXP3 GNMT HSD3B7 KCNH2 ABCB7 ALG11 ATP8B1 CCDC78 CNTN1 CYP11B1 DRC1 F11 FOXRED1 GNPAT HSPD1 KCNH5 ABCC2 ALG12 ATPAF2 CCDC8 CNTNAP1 CYP11B2 DSC2 F13A1 FRAS1 GNPTAB HSPG2 KCNJ10 ABCC8 ALG13 ATR CCDC88C CNTNAP2 CYP17A1 DSG1 F13B FREM1 GNPTG HUWE1 KCNJ11 ABCC9 ALG14 ATRX CCND2 COA5 CYP1B1 DSP F2 FREM2 GNS HYDIN KCNJ13 ABCD3 ALG2 AUH CCNO COG1 CYP24A1 DST F5 FRMD7 GORAB HYLS1 KCNJ2 ABCD4 ALG3 B3GALNT2 CCS COG4 CYP26C1 DSTYK F7 FTCD GP1BA IBA57 KCNJ5 ABHD5 ALG6 B3GAT3 CCT5 COG5 CYP27A1 DTNA F8 FTO GP1BB ICK KCNJ8 ACAD8 ALG8 B3GLCT CD151 COG6 CYP27B1 DUOX2 F9 FUCA1 GP6 ICOS KCNK3 ACAD9 ALG9 -

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature Into Vascularized Glomeruli Upon Experimental Transplantation

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation † Sazia Sharmin,* Atsuhiro Taguchi,* Yusuke Kaku,* Yasuhiro Yoshimura,* Tomoko Ohmori,* ‡ † ‡ Tetsushi Sakuma, Masashi Mukoyama, Takashi Yamamoto, Hidetake Kurihara,§ and | Ryuichi Nishinakamura* *Department of Kidney Development, Institute of Molecular Embryology and Genetics, and †Department of Nephrology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan; ‡Department of Mathematical and Life Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan; §Division of Anatomy, Juntendo University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan; and |Japan Science and Technology Agency, CREST, Kumamoto, Japan ABSTRACT Glomerular podocytes express proteins, such as nephrin, that constitute the slit diaphragm, thereby contributing to the filtration process in the kidney. Glomerular development has been analyzed mainly in mice, whereas analysis of human kidney development has been minimal because of limited access to embryonic kidneys. We previously reported the induction of three-dimensional primordial glomeruli from human induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. Here, using transcription activator–like effector nuclease-mediated homologous recombination, we generated human iPS cell lines that express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the NPHS1 locus, which encodes nephrin, and we show that GFP expression facilitated accurate visualization of nephrin-positive podocyte formation in -

Transcriptome Profiling and Molecular Pathway Analysis of Genes in Association with Salinity Adaptation in Nile Tilapia Oreochromis Niloticus

RESEARCH ARTICLE Transcriptome Profiling and Molecular Pathway Analysis of Genes in Association with Salinity Adaptation in Nile Tilapia Oreochromis niloticus Zhixin Xu1, Lei Gan1, Tongyu Li1, Chang Xu1, Ke Chen1, Xiaodan Wang1, Jian G. Qin2, Liqiao Chen1*, Erchao Li1* 1 Laboratory of Aquaculture Nutrition and Environmental Health, School of Life Sciences, East China Normal University, 500 Dongchuan Rd., Shanghai 200241, China, 2 School of Biological Sciences, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA 5001, Australia * [email protected] (EL); [email protected] (LC) Abstract Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus is a freshwater fish but can tolerate a wide range of salini- OPEN ACCESS ties. The mechanism of salinity adaptation at the molecular level was studied using RNA- Citation: Xu Z, Gan L, Li T, Xu C, Chen K, Wang X, Seq to explore the molecular pathways in fish exposed to 0, 8, or 16 (practical salinity unit, et al. (2015) Transcriptome Profiling and Molecular psu). Based on the change of gene expressions, the differential genes unions from freshwa- Pathway Analysis of Genes in Association with Salinity Adaptation in Nile Tilapia Oreochromis ter to saline water were classified into three categories. In the constant change category (1), niloticus. PLoS ONE 10(8): e0136506. doi:10.1371/ steroid biosynthesis, steroid hormone biosynthesis, fat digestion and absorption, comple- journal.pone.0136506 ment and coagulation cascades were significantly affected by salinity indicating the pivotal Editor: Marie-Joelle Virolle, University Paris South, roles of sterol-related pathways in response to salinity stress. In the change-then-stable cat- FRANCE egory (2), ribosomes, oxidative phosphorylation, signaling pathways for peroxisome prolif- Received: June 4, 2015 erator activated receptors, and fat digestion and absorption changed significantly with Accepted: August 4, 2015 increasing salinity, showing sensitivity to salinity variation in the environment and a responding threshold to salinity change. -

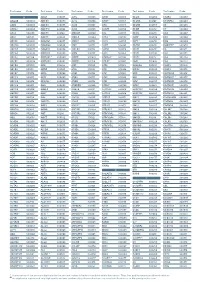

Supplemetary Table 2. List of Genes Down-Regulated in LPAR6 Knocked Down Cells

Supplemetary Table 2. List of genes down-regulated in LPAR6 knocked down cells g# initial alias c# converted alias name description namespace 1 NM_002317.5 1.1 ENSG00000113083 LOX lysyl oxidase [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:6664] REFSEQ_MRNA 2 NM_006183.4 2.1 ENSG00000133636 NTS neurotensin [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:8038] REFSEQ_MRNA 3 NM_005213.3 3.1 ENSG00000121552 CSTA cystatin A (stefin A) [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:2481] REFSEQ_MRNA 4 NM_007231.3 4.1 ENSG00000087916 SLC6A14 solute carrier family 6 (amino acid transporter), member 14 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:11047] REFSEQ_MRNA 5 NM_001873.2 5.1 ENSG00000109472 CPE carboxypeptidase E [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:2303] REFSEQ_MRNA 6 NM_019856.1 6.1 ENSG00000101605 MYOM1 myomesin 1, 185kDa [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:7613] REFSEQ_MRNA 7 NM_032590.4 7.1 ENSG00000089094 KDM2B lysine (K)-specific demethylase 2B [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:13610] REFSEQ_MRNA 8 NM_001901.2 8.1 ENSG00000118523 CTGF connective tissue growth factor [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:2500] REFSEQ_MRNA 9 NM_007183.2 9.1 ENSG00000184363 PKP3 plakophilin 3 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:9025] REFSEQ_MRNA 10 NM_182965.2 10.1 ENSG00000176170 SPHK1 sphingosine kinase 1 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:11240] REFSEQ_MRNA 11 NM_152423.4 11.1 ENSG00000157502 MUM1L1 melanoma associated antigen (mutated) 1-like 1 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:26583] REFSEQ_MRNA 12 NM_002923.3 12.1 ENSG00000116741 RGS2 regulator of G-protein signaling 2, 24kDa [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:9998] REFSEQ_MRNA 13 NR_003038.2 13.1 N/A N/A N/A N/A 14 NM_080862.1 14.1 ENSG00000175093 SPSB4 splA/ryanodine receptor -

CENTOGENE's Severe and Early Onset Disorder Gene List

CENTOGENE’s severe and early onset disorder gene list USED IN PRENATAL WES ANALYSIS AND IDENTIFICATION OF “PATHOGENIC” AND “LIKELY PATHOGENIC” CENTOMD® VARIANTS IN NGS PRODUCTS The following gene list shows all genes assessed in prenatal WES tests or analysed for P/LP CentoMD® variants in NGS products after April 1st, 2020. For searching a single gene coverage, just use the search on www.centoportal.com AAAS, AARS1, AARS2, ABAT, ABCA12, ABCA3, ABCB11, ABCB4, ABCB7, ABCC6, ABCC8, ABCC9, ABCD1, ABCD4, ABHD12, ABHD5, ACACA, ACAD9, ACADM, ACADS, ACADVL, ACAN, ACAT1, ACE, ACO2, ACOX1, ACP5, ACSL4, ACTA1, ACTA2, ACTB, ACTG1, ACTL6B, ACTN2, ACVR2B, ACVRL1, ACY1, ADA, ADAM17, ADAMTS2, ADAMTSL2, ADAR, ADARB1, ADAT3, ADCY5, ADGRG1, ADGRG6, ADGRV1, ADK, ADNP, ADPRHL2, ADSL, AFF2, AFG3L2, AGA, AGK, AGL, AGPAT2, AGPS, AGRN, AGT, AGTPBP1, AGTR1, AGXT, AHCY, AHDC1, AHI1, AIFM1, AIMP1, AIPL1, AIRE, AK2, AKR1D1, AKT1, AKT2, AKT3, ALAD, ALDH18A1, ALDH1A3, ALDH3A2, ALDH4A1, ALDH5A1, ALDH6A1, ALDH7A1, ALDOA, ALDOB, ALG1, ALG11, ALG12, ALG13, ALG14, ALG2, ALG3, ALG6, ALG8, ALG9, ALMS1, ALOX12B, ALPL, ALS2, ALX3, ALX4, AMACR, AMER1, AMN, AMPD1, AMPD2, AMT, ANK2, ANK3, ANKH, ANKRD11, ANKS6, ANO10, ANO5, ANOS1, ANTXR1, ANTXR2, AP1B1, AP1S1, AP1S2, AP3B1, AP3B2, AP4B1, AP4E1, AP4M1, AP4S1, APC2, APTX, AR, ARCN1, ARFGEF2, ARG1, ARHGAP31, ARHGDIA, ARHGEF9, ARID1A, ARID1B, ARID2, ARL13B, ARL3, ARL6, ARL6IP1, ARMC4, ARMC9, ARSA, ARSB, ARSL, ARV1, ARX, ASAH1, ASCC1, ASH1L, ASL, ASNS, ASPA, ASPH, ASPM, ASS1, ASXL1, ASXL2, ASXL3, ATAD3A, ATCAY, ATIC, ATL1, ATM, ATOH7, -

Downloaded from Here

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/017566; this version posted November 19, 2015. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 1 Testing for ancient selection using cross-population allele 2 frequency differentiation 1;∗ 3 Fernando Racimo 4 1 Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA 5 ∗ E-mail: [email protected] 6 1 Abstract 7 A powerful way to detect selection in a population is by modeling local allele frequency changes in a 8 particular region of the genome under scenarios of selection and neutrality, and finding which model is 9 most compatible with the data. Chen et al. [2010] developed a composite likelihood method called XP- 10 CLR that uses an outgroup population to detect departures from neutrality which could be compatible 11 with hard or soft sweeps, at linked sites near a beneficial allele. However, this method is most sensitive 12 to recent selection and may miss selective events that happened a long time ago. To overcome this, 13 we developed an extension of XP-CLR that jointly models the behavior of a selected allele in a three- 14 population tree. Our method - called 3P-CLR - outperforms XP-CLR when testing for selection that 15 occurred before two populations split from each other, and can distinguish between those events and 16 events that occurred specifically in each of the populations after the split. -

PIGV Gene Phosphatidylinositol Glycan Anchor Biosynthesis Class V

PIGV gene phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class V Normal Function The PIGV gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called GPI mannosyltransferase 2. This enzyme takes part in a series of steps that produce a molecule called a glycosylphosphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. Specifically, GPI mannosyltransferase 2 adds the second of three molecules of a complex sugar called mannose to the GPI anchor. This step takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum, which is a structure involved in protein processing and transport within cells. The complete GPI anchor attaches (binds) to various proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. After the anchor and protein are bound, the anchor attaches itself to the outer surface of the cell membrane, ensuring that the protein will be available when it is needed. Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes Mabry syndrome At least 14 mutations in the PIGV gene have been found to cause Mabry syndrome, a condition characterized by intellectual disability, distinctive facial features, increased levels of an enzyme called alkaline phosphatase in the blood (hyperphosphatasia), and other signs and symptoms. These mutations change single protein building blocks ( amino acids) in the GPI mannosyltransferase 2 enzyme. The altered protein is less able to add mannose to the forming GPI anchor. The incomplete GPI anchor cannot attach to proteins; without the anchor, the proteins cannot bind to the cell membrane and are released from the cell. An enzyme called alkaline phosphatase is normally attached to a GPI anchor. However, when the anchor is impaired, alkaline phosphatase cannot be anchored to the cell membrane. Instead, alkaline phosphatase is released from the cell. -

Downregulation of Carnitine Acyl-Carnitine Translocase by Mirnas

Page 1 of 288 Diabetes 1 Downregulation of Carnitine acyl-carnitine translocase by miRNAs 132 and 212 amplifies glucose-stimulated insulin secretion Mufaddal S. Soni1, Mary E. Rabaglia1, Sushant Bhatnagar1, Jin Shang2, Olga Ilkayeva3, Randall Mynatt4, Yun-Ping Zhou2, Eric E. Schadt6, Nancy A.Thornberry2, Deborah M. Muoio5, Mark P. Keller1 and Alan D. Attie1 From the 1Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin; 2Department of Metabolic Disorders-Diabetes, Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, New Jersey; 3Sarah W. Stedman Nutrition and Metabolism Center, Duke Institute of Molecular Physiology, 5Departments of Medicine and Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Durham, North Carolina. 4Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Louisiana State University system, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; 6Institute for Genomics and Multiscale Biology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York. Corresponding author Alan D. Attie, 543A Biochemistry Addition, 433 Babcock Drive, Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, (608) 262-1372 (Ph), (608) 263-9608 (fax), [email protected]. Running Title: Fatty acyl-carnitines enhance insulin secretion Abstract word count: 163 Main text Word count: 3960 Number of tables: 0 Number of figures: 5 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online June 26, 2014 Diabetes Page 2 of 288 2 ABSTRACT We previously demonstrated that micro-RNAs 132 and 212 are differentially upregulated in response to obesity in two mouse strains that differ in their susceptibility to obesity-induced diabetes. Here we show the overexpression of micro-RNAs 132 and 212 enhances insulin secretion (IS) in response to glucose and other secretagogues including non-fuel stimuli. We determined that carnitine acyl-carnitine translocase (CACT, Slc25a20) is a direct target of these miRNAs. -

Epileptic Encephalopathy and Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy Precision Panel

Epileptic Encephalopathy and Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy Precision Panel Overview Epileptic Encephalopathy and Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy (EIEE) describes a clinical and genetic heterogeneous group of epilepsy syndromes associated with severe cognitive and behavioral abnormalities. Clinically these disorders vary in their age of onset, developmental outcome, etiologies, neuropsychological deficits, seizure types and prognosis. The difference between these two entities relies in the age of onset, EIEE manifests in the first year of life. Identifiable factors that may influence the course and degree of cognitive and behavioral impairment in these disorders include underlying etiology, age of onset, seizure frequency and severity, cumulative detrimental effect and genetic factors. Genetically these disorders can be caused by de novo mutations, but they can also be inherited in an autosomal dominant, recessive or X-linked pattern. The Igenomix Epileptic Encephalopathy and Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy (EIEE) Precision Panel can serve as an accurate and directed diagnostic tool as well as for a differential diagnosis for early onset epilepsy ultimately leading to a better management and prognosis of the disease. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the genes involved in this disease using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to fully understand the spectrum of relevant genes involved. Indications The Igenomix Epileptic Encephalopathy and Early Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy (EIEE) Precision Panel is indicated in patients with a clinical suspicion or diagnosis presenting with the following manifestations: ‐ Early-onset seizures ‐ Metabolic abnormalities ‐ Myoclonic and partial motor seizures ‐ Infantile spasms Clinical Utility The clinical utility of this panel is: - The genetic and molecular diagnosis for an accurate clinical diagnosis of a symptomatic patient. -

POSITIVE RESULT Pathogenic Variant Identified

CENTOGENE AG Am Strande 7 • 18055 Rostock • Germany xxx Order no.: xxx Order received: xxx Sample type: blood, EDTA Sample collection date: xxx Report date: xxx Report type: Final Report Patient no.: xxx, First Name: xxx, Last Name: xxx DOB: xxx, Sex: male, Your ref.: xxx Additional report recipient(s): xxx Test(s) requested: CentoGenome® CLINICAL INFORMATION Abnormal facial shape; Abnormality of the eye; Abnormality of the musculature; Abnormality of the nervous system; Abnormality of the skeletal system; Anteverted ears; Arachnodactyly; Broad-based gait; Congenital onset; Decreased muscle mass; Global developmental delay; Hearing impairment; High, narrow palate; Hyperactive deep tendon reflexes; Joint hypermobility; Long face; Long nose; Microphthalmia; Myopathic facies; Narrow chest; Ophthalmoplegia; Protruding ear; Protruding tongue; Rod-cone dystrophy; Spasticity; Tall chin; Wide nasal bridge (Clinical information indicated above follows HPO nomenclature.) Family history: Yes. Consanguineous parents: Yes. We performed sequencing analysis focusing on the phenotype of this patient. Please see our concurrent reports xxx, and xxx.. POSITIVE RESULT Pathogenic variant identified INTERPRETATION A homozygous pathogenic variant was identified in the AHI1 gene. A genetic diagnosis of autosomal recessive Joubert syndrome type 3 is confirmed. RECOMMENDATIONS Genetic counselling is recommended. > Contact Details Tel.: +49 (0)381 80113 416 CLIA registration 99D2049715; CAP registration 8005167. Scientific use of Fax: +49 (0)381 80113 401 these results requires permission of CENTOGENE. If you would like to download your reports from our web portal, please contact us to receive [email protected] your login and password. More information is available at www.centogene.com www.centogene.com or [email protected]. -

Aagab S00002 Aars S00003 Aars2 S00004 Aass S02483

Test name Code Test name Code Test name Code Test name Code Test name Code Test name Code A ADAR S00053 ALPL S00105 ARSB S00153 BCL10 S02266 C5AR2 S00263 AAGAB S00002 ADCK3 S00054 ALS2 S00106 ARSE * S00154 BCL11A S02167 C5ORF42 S00264 AARS S00003 ADCK4 S00055 ALX3 S00107 ARX S00155 BCL11B S02358 C6 S00265 AARS2 S00004 ADCY10 S02094 ALX4 S00108 ASAH1 S00156 BCOR S00212 C7 S00266 AASS S02483 ADCY3 S02184 AMACR S00109 ASL S00157 BCS1L S00213 C8A S00267 ABAT S02191 ADCY5 S02226 AMELX S02289 ASNS * S02508 BDNF S02509 C8B S00268 ABCA1 S00005 ADGRG1 S00057 AMER1 S00110 ASPA S00158 BDP1 * S00214 C8G S00269 ABCA12 S00006 ADGRG6 S02548 AMH S00111 ASPH S02425 BEAN1 S00215 C8ORF37 S00270 ABCA3 S00007 ADGRV1 S00058 AMHR2 S00112 ASPM S00159 BEST1 S00216 C9 S00271 ABCA4 S00008 ADIPOQ S00059 AMN S00113 ASS1 S00160 BFSP1 S02280 CA2 S00272 ABCA7 S02106 ADIPOR1 * S00060 AMPD1 S02670 ATAD3A * S02196 BFSP2 S00217 CA4 S02303 ABCB11 S00009 ADIPOR2 S00061 AMPD2 S02128 ATCAY S00162 BGN S02633 CA8 S00273 ABCB4 S00010 ADK S02595 AMT S00114 ATF6 S00163 BHLHA9 S00218 CABP2 S00274 ABCB6 S00011 ADNP S02320 ANG S00115 ATIC S02458 BICD2 S00220 CABP4 S00275 ABCB7 S00012 ADSL S00062 ANK1 S00116 ATL1 S00164 BIN1 S00221 CACNA1A S00276 ABCC2 S00013 AFF2 S00063 ANK2 S00117 ATL3 S00165 BLK S00222 CACNA1C * S00277 ABCC6 * S00014 AFG3L2 * S00064 ANKH S00118 ATM S00166 BLM S00223 CACNA1D S00278 ABCC8 S00015 AGA S00065 ANKRD11 * S02140 ATOH7 S02390 BLNK S02281 CACNA1F S00279 ABCC9 S00016 AGBL5 S02452 ANKS6 S00121 ATP13A2 S00168 BLOC1S3 S00224 CACNA1H S00280 ABCD1 * S00017 AGK *