Final Copy 2019 01 23 Kilgar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

MUSICAL NOTES. Orchestra, at Long Beach, Are Deservedly Praised

THE MUSICAL CRITIC AND TRADE REVIEW. September 5th, 1880 SCHREINER.—Mr. Kleophas Schreiner's Military Band and String MUSICAL NOTES. Orchestra, at Long Beach, are deservedly praised. There is a great deal of strength and precision in the performances, and Mr. Schreiner has a good AT HOME. and varied repertoire. Some of the soloists are excellent. Mr. Hoch is ap- DODWORTH.—Harvey B. Dodworth was engaged to furnish the music plauded after his cornet performances, and Mr. Neubech, the concert master for the Rockaway Beach Improvement Company at the big hotel; but as the of the orchestra, has made many friends by an artistic rendering of Max hotel -was not finished, he was forced to remain idle seven weeks. He now Bruch's first Concerto for the Violin. has a claim against the company for $10,080. THAYER.—The Kate Thayer Concert Company, under the management MARETZEK.—Max Maretzek has accepted the position of "Professor of of Mr. Will E. Chapman, will enter upon a concert tournee on October 17. the School for Operatic Training," in the College of Music of Cincinnati, The company comprises Miss Kate Thayer, Miss Maurer, pianist, the Spanish and "will enter upon his duties about the middle of this month. Students, and some other artistes. Whether the company will appear in New York during the season, we do not know, as the dates of the entire- STEBNBERG.—Heir Constantin Sternberg, a Russian piano virtuoso, season have not been settled upon yet. has been engaged for 100 concerts in America. He will arrive in New York in September. -

“America” on Nineteenth-Century Stages; Or, Jonathan in England and Jonathan at Home

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME by Maura L. Jortner BA, Franciscan University, 1993 MA, Xavier University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by It was defended on December 6, 2005 and approved by Heather Nathans, Ph.D., University of Maryland Kathleen George, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Attilio Favorini, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, Ph.D., Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Maura L. Jortner 2005 iii PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME Maura L. Jortner, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation, prepared towards the completion of a Ph.D. in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, examines “Yankee Theatre” in America and London through a post-colonial lens from 1787 to 1855. Actors under consideration include: Charles Mathews, James Hackett, George Hill, Danforth Marble and Joshua Silsbee. These actors were selected due to their status as iconic performers in “Yankee Theatre.” The Post-Revolutionary period in America was filled with questions of national identity. Much of American culture came directly from England. American citizens read English books, studied English texts in school, and watched English theatre. They were inundated with English culture and unsure of what their own civilization might look like. -

A Moor Propre: Charles Albert Fechter's Othello

A MOOR PROPRE: CHARLES ALBERT FECHTER'S OTHELLO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Scott Phillips, B.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University •· 1992 Thesis Committee: Approved by Alan Woods Joy Reilly Adviser Department of Theatre swift, light-footed, and strange, with his own dark face in a rage,/ Scorning the time-honoured rules Of the actor's conventional schools,/ Tenderly, thoughtfully, earnestly, FECHTER comes on to the stage. (From "The Three Othellos," Fun 9 Nov. 1861: 76.} Copyright by Matthew Scott Phillips ©1992 J • To My Wife Margaret Freehling Phillips ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express heartfelt appreciation to the members of my thesis committee: to my adviser, Dr. Alan Woods, whose guidance and insight made possible the completion of this thesis, and Dr. Joy Reilly, for whose unflagging encouragement I will be eternally grateful. I would also like to acknowledge the invaluable services of the British Library, the Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee Theatre Research Institute and its curator, Nena Couch. The support and encouragement given me by my family has been outstanding. I thank my father for raising my spirits when I needed it and my mother, whose selflessness has made the fulfillment of so many of my goals possible, for putting up with me. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Maggie, for her courage, sacrifice and unwavering faith in me. Without her I would not have come this far, and without her I could go no further. -

A Bibliographr of the LIFE - AND:DRAMATIC AET OFDIGH BGUGICAULT5

A bibliography of the life and dramatic art of Dion Boucicault; with a handlist of plays Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Livieratos, James Nicholas, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 23:28:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318894 A BiBLIOGRAPHr OF THE LIFE - AND:DRAMATIC AET OFDIGH BGUGICAULT5 ■w i t h A M i d l i s t of pla ys v :': . y '- v ■ V; - , ■■ : ■ \.." ■ .' , ' ' „ ; James H 0 Livieratos " ###*##* " A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPART1#!NT OF DRAMA : ^ : Z; In;Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements ... ■ ' For the Degree : qT :.. y , : ^■ . MASTER OF ARTS : •/ : In the Graduate College ■ / UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA ; 1 9 6 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledg ment of source is made. Requests for permission for ex tended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com SirArthurSullivan ArthurLawrence,BenjaminWilliamFindon,WilfredBendall \ SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN: Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. From the Portrait Pruntfd w 1888 hv Sir John Millais. !\i;tn;;;i*(.vnce$. i-\ !i. W. i ind- i a. 1 V/:!f ;d B'-:.!.i;:. SIR ARTHUR SULLIVAN : Life-Story, Letters, and Reminiscences. By Arthur Lawrence. With Critique by B. W. Findon, and Bibliography by Wilfrid Bendall. London James Bowden 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, W.C. 1899 /^HARVARD^ UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 5 1956 PREFACE It is of importance to Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself that I should explain how this book came to be written. Averse as Sir Arthur is to the " interview " in journalism, I could not resist the temptation to ask him to let me do something of the sort when I first had the pleasure of meeting ^ him — not in regard to journalistic matters — some years ago. That permission was most genially , granted, and the little chat which I had with J him then, in regard to the opera which he was writing, appeared in The World. Subsequent conversations which I was privileged to have with Sir Arthur, and the fact that there was nothing procurable in book form concerning our greatest and most popular composer — save an interesting little monograph which formed part of a small volume published some years ago on English viii PREFACE Musicians by Mr. -

I Have a Song to Sing O! Program.Pdf

Musical Numbers With Cat-like Tread, Upon Our Prey We Steal (The Pirates of Penzance) ...........................Ensemble I Have a Song to Sing, O! (The Yeomen of the Guard) ..................... James Mills and Sarah Caldwell Smith Am I Alone and Unobserved? (Patience)............................................... James Mills A British Tar (H.M.S. Pinafore) ................................Alex Corson, Albert Bergeret, Artistic Director Matthew Wages, David Wannen I’m Called Little Buttercup Wand’ring Minstrels (H.M.S. Pinafore) .............. Angela Christine Smith in We’re Called Gondolieri (The Gondoliers) ...................................Alex Corson and Matthew Wages Take a Pair of Sparkling Eyes (The Gondoliers) ...................................Alex Corson Oh, Better Far to Live and Die (The Pirates of Penzance) ................. Matthew Wages and Men Director: James Mills When All Night Long a Chap Remains (Iolanthe) ..........................................David Wannen Music Director & Conductor: Albert Bergeret Executive Producer: David Wannen Three Little Maids From School are We (The Mikado) .............................Rebecca Hargrove, Editor: Danny Bristoll Angela Christine Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith Sarah Caldwell Smith, Soprano The Sun, Whose Rays are All Ablaze Rebecca Hargrove, Soprano (The Mikado) ..............................Rebecca Hargrove Angela Christine Smith, Contralto Here’s a How-de-do! Alex Corson, Tenor (The Mikado) ......................................Alex Corson, James Mills, Comic Baritone James -

Colnaghistudiesjournal Journal-01

EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Xavier F. Salomon Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator, The Frick Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Collection, New York. Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Salvador Salort-Pons Director, President & CEO, Detroit Francesca Baldassari Art Historian. Institute of Arts. Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Research Associate in Art History, Jack Soultanian Conservator, The Metropolitan Museum of Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is Art, New York. The Open University. to publish texts on significant pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition Bruce Boucher Director, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Nicola Spinosa Former Director of Museo di Capodimonte, Naples. that have recently come to light or about which new research is underway, as well as Till-Holger Borchert Director, Musea Brugge. Carl Strehlke Adjunct Emeritus, Philadelphia Museum of Art. on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the Antonia Boström Keeper of Sculpture, Metalwork, Ceramics Holly Trusted Senior Curator of Sculpture, Victoria & Albert broader context of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. & Glass, Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Museum, London. Edgar Peters Bowron Former Audrey Jones Beck Curator of Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Benjamin van Beneden Director, Rubenshuis, Antwerp. European Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Editorial Committee, composed of specialists on painting, sculpture, architecture, Mark Westgarth Programme Director and Lecturer in Art History Xavier Bray Director, The Wallace Collection, London. -

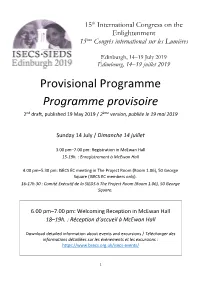

Programme19may.Pdf

15th International Congress on the Enlightenment 15ème Congrès international sur les Lumières Edinburgh, 14–19 July 2019 Édimbourg, 14–19 juillet 2019 Provisional Programme Programme provisoire 2nd draft, published 19 May 2019 / 2ème version, publiée le 19 mai 2019 Sunday 14 July / Dimanche 14 juillet 3.00 pm–7.00 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 15-19h. : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 4.00 pm–5.30 pm: ISECS EC meeting in The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square (ISECS EC members only). 16-17h.30 : Comité Exécutif de la SIEDS à The Project Room (Room 1.06), 50 George Square. 6.00 pm–7.00 pm: Welcoming Reception in McEwan Hall 18–19h. : Réception d’accueil à McEwan Hall Download detailed information about events and excursions / Télécharger des informations détaillées sur les événements et les excursions : https://www.bsecs.org.uk/isecs-events/ 1 Monday 15 July / Lundi 15 juillet 8.00 am–6.30 pm: Registration in McEwan Hall 8-18h.30 : Enregistrement à McEwan Hall 9.00 am: Opening ceremony and Plenary 1 in McEwan Hall 9h. : Cérémonie d’ouverture et 1e Conférence Plénière à McEwan Hall Opening World Plenary / Plénière internationale inaugurale Enlightenment Identities: Definitions and Debates Les identités des Lumières: définitions et débats Chair/Président : Penelope J. Corfield (Royal Holloway, University of London and ISECS) Tatiana V. Artemyeva (Herzen State University, Russia) Sébastien Charles (Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Canada) Deidre Coleman (University of Melbourne, Australia) Sutapa Dutta (Gargi College, University of Delhi, India) Toshio Kusamitsu (University of Tokyo, Japan) 10.30 am: Coffee break in McEwan Hall 10h.30 : Pause-café à McEwan Hall 11.00 am, Monday 15 July: Session 1 (90 minutes) 11h. -

Prints Collection

Prints Collection: An Inventory of the Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Prints Collection Title: Prints Collection Dates: 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825) Extent: 54 document boxes, 7 oversize boxes (33.38 linear feet) Abstract: The collection consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. RLIN Record #: TXRC02-A1 Language: English. Access Open for research Administrative Information Provenance The Prints Collection was assembled by Theater Arts staff, primarily from the Messmore Kendall Collection which was acquired in 1958. Other sources were the Robert Downing and Albert Davis collections. Processed by Helen Baer and Antonio Alfau, 2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Prints Collection Scope and Contents The Prints Collection, 1669-1906 (bulk 1775-1825), consists of ca. 8,000 prints, the great majority of which depict British and American theatrical performers in character or in personal portraits. The collection is organized in three series: I. Individuals, 1669-1906 (58.25 boxes), II. Theatrical Prints, 1720-1891 (1.75 boxes), and III. Works of Art and Miscellany, 1827-82 (1 box), each arranged alphabetically by name or subject. The prints found in this collection were made by numerous processes and include lithographs, woodcuts, etchings, mezzotints, process prints, and line blocks; a small number of prints are hand-tinted. A number of the prints were cut out from books and periodicals such as The Illustrated London News, The Universal Magazine, La belle assemblée, Bell's British Theatre, and The Theatrical Inquisitor; others comprised sets of plates of dramatic figures such as those published by John Tallis and George Gebbie, or by the toy theater publishers Orlando Hodgson and William West. -

![No Thoroughfare: a Drama [Correct First Edition] – by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins (1867)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4700/no-thoroughfare-a-drama-correct-first-edition-by-charles-dickens-and-wilkie-collins-1867-1584700.webp)

No Thoroughfare: a Drama [Correct First Edition] – by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins (1867)

No Thoroughfare: A Drama [correct first edition] – by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins (1867) A carefully-posed cast photo showing Joey Ladle (Benjamin Webster), Sally Goldstraw (Mrs. Alfred Mellon), George Vendale (Henry G. Neville), Jules Obenreizer (Charles Albert Fechter), Marguerite (Carlotta Leclercq), Walter Wilding (John Billington), and Bintrey (George G. Belmore). Foreword What was the most successful play Dickens worked on? How much did he contribute to it? And, why has text of the play gone unseen until today? The first question has an easy answer—the most successful play claiming Dickens as playwright was No Thoroughfare . The piece was a dramatization of the short story of the same name, which had appeared in the Christmas Number of All the Year Round the same year . The Christmas Story and the play are always credited to “Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins”, but the drama was, in fact, written almost entirely by Collins, working under Dickens’s long-distance supervision. Also assisting in the adaptation was the actor Charles Albert Fechter, a mutual friend to the two authors, whose role as the villainous Obenreizer would be the great hit of the performance. A letter from Dickens to an American publisher tells how he initiated events (1 Nov 1867): I will bring you out the early proof of the Xmas No. We publish it here on the 12th. of December. I am planning it out into a play for Wilkie Collins to manipulate after I sail, and have arranged for Fechter to go to the Adelphi Theatre and play a Swiss in it. -

Masarykova Univerzita Fenomén Gilbert

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA FENOMÉN GILBERT & SULLIVAN – VZNIK ANGLICKÉ OPERETY Disertační práce Monika Bártová Vedoucí práce: prof. PhDr. Julius Gajdoš, Ph.D. Ústav pro studium divadla a interaktivních médií Brno 2006 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracovala samostatně, pouze s použitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. Monika Bártová 2 OBSAH ÚVODEM 5 I. OPERETA – VYMEZENÍ POJMU A VZNIK ŽÁNRU 11 I. 1. Opereta jako svébytný umělecký žánr 11 I. 2. Opereta jako společenská satira 13 I. 3. Pojem opereta 18 I. 4. Inspirační zdroje operety: opéra comique, café concert, tančírny 21 I. 5. Počátky nového žánru: J. Offenbach 28 I. 6. Témata operet a jejich postavy 30 I. 7. Opereta a vernacular 34 I. 8. Opereta versus muzikál 36 II. HUDEBNĚ-ZÁBAVNÉ DIVADLO V BRITÁNII: OD MASQUES K MUSIC HALLU 40 II.1. Počátky hudebně-zábavného divadla v Británii 40 II. 2. Masques 40 II. 3. Ballad opera 42 II. 4. Pantomima 45 II. 5. Extravaganza 50 II. 6. Burleska 52 II. 7. Music-hall 55 III. GILBERT&SULLIVAN: ANGLICKÁ OPERETA 60 III. 1. Gilbert před Sullivanem 64 III. 2. Sullivan před Gilbertem 72 III. 3. První společná opereta: Thespis 79 III. 4. Trial by Jury 85 III. 5. The Sorcerer 91 III. 6. H.M.S. Pinafore 99 III. 7. The Pirates of Penzance 113 3 III. 8. Patience 124 III. 9. Iolanthe 134 III.10. Princess Ida 142 III.11. The Mikado 150 III.12. Ruddigore 160 III.13. The Yeomen of the Guard 167 III.14. The Gondoliers 173 III.15. Utopia Limited 180 III.16. The Grand Duke 188 III.17.