A Case of Dental Fusion in Primary Dentition from Late Bronze Age Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supernumerary Teeth

Volume 22, Number 1, 2009 ISSN 1096-9411 Dental Anthropology A Publication of the Dental Anthropology Association Dental Anthropology Volume 22, Number 1, 2009 Dental Anthropology is the Official Publication of the Dental Anthropology Association. Editor: Edward F. Harris Editorial Board Kurt W. Alt (2004-2009) Richard T. Koritzer (2004-2009) A. M. Haeussler (2004-2009) Helen Liversidge (2004-2009) Tseunehiko Hanihara (2004-2009) Yuji Mizoguchi (2006-2010) Kenneth A. R. Kennedy (2006-2010) Lindsay C. Richards (2006-2010) Jules A. Kieser (2004-2009) Phillip W. Walker (2006-2010) Officers of the Dental Anthropology Association Brian E. Hemphill (California State University, Bakersfield) President (2008-2010) G. Richard Scott (University of Nevada, Reno) President-Elect (2008-2010) Loren R. Lease (Youngstown State University, Ohio) Secretary-Treasurer (2007-2009) Simon W. Hillson (University College London) Past-President (2006-2008) Address for Manuscripts Dr. Edward F. Harris College of Dentistry, University of Tennessee 870 Union Avenue, Memphis, TN 38163 U.S.A. E-mail address: [email protected] Address for Book Reviews Dr. Greg C. Nelson Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon Condon Hall, Eugene, Oregon 97403 U.S.A. E-mail address: [email protected] Published at Craniofacial Biology Laboratory, Department of Orthodontics College of Dentistry, The Health Science Center University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN 38163 U.S.A. The University of Tennessee is an EEO/AA/Title IX/Section 504/ADA employer 1 Strong genetic influence on hypocone expression of permanent maxillary molars in South Australian twins Denice Higgins*, Toby E. Hughes, Helen James, Grant C. Townsend Craniofacial Biology Research Group, School of Dentistry, The University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005 ABSTRACT An understanding of the role of genetic be larger in males although this was not statistically influences on dental traits is important in the areas of significant. -

Comunicaciones Pósteres

1113-5181/18/26.1/59-101 ODONTOLOGÍA PEDIÁTRICA ODONTOL PEDIÁTR (Madrid) COPYRIGHT © 2018 SEOP Y ARÁN EDICIONES, S. L. Vol. 26, N.º 1, pp. 59-101, 2018 Comunicaciones Pósteres REVISIÓN BIBLIOGRÁFICA resulta imperativo que los pediatras incrementen su nivel de conocimiento sobre la CPI y faciliten más información eficaz a los padres sobre cuidados orales y la necesidad de visitar al odontopediatra. Los padres poseen escasos conocimientos sobre la caries, especialmente acerca de su tratamiento. 0002. CONOCIMIENTO DE PEDIATRAS Y PADRES SOBRE LA CARIES DE LA PRIMERA INFANCIA Enrech Rivero, J.; Sande López, L.; Martínez 0012. ENFERMEDAD CELIACA Y ALTERACIONES Martín, N.; Martín Olivera, E.; Delgado Castro, N. DEL ESMALTE DENTAL. REVISIÓN SISTEMÁTICA Universidad Antonio de Nebrija. Madrid López Durán, M.; Riolobos González, M.; Introducción: La prevalencia universal de la caries es un Costa Ferrer, F.; Khalifi Abdelkader, C.; recordatorio constante de la necesidad de proporcionar una edu- de la Cuesta Aubert, A. cación eficaz para la prevención en la salud oral. La caries de la Universidad Alfonso X el Sabio. Villanueva de la Cañada, primera infancia (CPI) es una enfermedad infecciosa, crónica Madrid y transmisible, con una etiología multifactorial, considerada actualmente un grave problema de salud pública universal en Introducción: La enfermedad celíaca (EC) es una enfer- niños en edad escolar. Los datos epidemiológicos muestran medad sistémica inmunomediada, provocada por el gluten que la mejor manera de controlar la CPI se basa precisamente y prolaminas, en individuos genéticamente susceptibles; se en la prevención, que en el niño consistirá en actuar sobre los caracteriza por la presencia de una combinación variable de factores etiológicos, como mejorar los hábitos dietéticos e hi- manifestaciones clínicas dependientes del gluten, anticuerpos giénicos. -

Remembered Questions Very High Yield Found This on the Internet ,It

Remembered Questions Very High Yield Found this on the internet ,It says 2012 not sure if it is remembered questions or not but i think soCredit to : Alisha Reynolds 1.Basal cell carcinoma !n the face 2."ecrease response to cellular si$nal %ecrosis &.Inner'ation: (hat does the 'a$us inner'ate belo( the intestine Colon (descendin$ colon*+ ,.Someone climb mount .'erest, and the #ressure (as atmos#heric #ressure 2/0 mmH$, (hat is the 102+ 212 of 1!2, so .21 x 2/04 /0mm0$ /.5hat is #ercenta$e of #ost teeth in the max arch+(ask in di6erent (ays) 10718482./2+++ 8.5hat $oes bt( the su# and middle constrictor? -tylo#haryn$eous m. 9.Fumerase 0ydrolase :.5hat runs thru the stylomastoid foramen C%9 ;.5hat is the def enzyme of tay sa hs? It is =M2??? 10.5hat branch $oes of the ECA $oes do(n to the hyoid+ Su# thyroid artery? 11.5here does the 'ertebral artery ome out from? Foramen ma$num 12.@racheostomy C8 1&.5hat omes out of the ext auditory meatus Cn 9 and : 1,.5hat does the strai$ht sinus drain into+ Internal Au$ular 'ein 1/.5hat #art #a#illae doesn't ha'e taste bud+ Filliform 18.5hat ner'e #rovides sensory to the ant 27& of the ton$ue+ Cin$ual n. 19.Ea$les syndrome -tylohyoid li$ament 1:.5hich of the follo(in$ only #roduces mu ous Sublin$ual $land 1;.Case question: (hat (as (ron$ (ith lady...osteoarthritis DDD 20.B12 Me$oloblastic anemia 21.Sensory to the face in the thalamus E1> 22.5hat $oes bt( the #ala$lossus and #alato#haryn$eus? 1alatine tonsil 2&.5hat inner'ates the the sternohyoid, sternthyroid Ansa cer'acalis (c1D &* 2,.5hat forms the face Frontal #rocess and branchial arch 2 2/.5hat inserts to the orinoid #rocess @emporalis 28.5hat retrudes the mandible 1ost fibers of temporalis 29.A "r. -

Pediatric Dentistry

Pediatric Dentistry Age and curricular differences could influence in the model questionnaire previous data); particularly clinical knowledge and perception of molar incisor 14% of the sample asked for updates on therapeutic hypomineralisation amongst dental professionals strategies. Baroni C., Gatto M.R., Prati C.,Manton D.J.* Evalutation of an imaging software for 3D rendering Unibo, Italy, DIBINEM of deciduous teeth *University of Melbourne, Australia, Dental Dept Battaglia E., Corridore D., Costantini R., Salucci A., Di Giorgio Aim: This study investigated the relationships between G., Petrazzuoli N., Sbarbaro C., Perrone A., Taddei L., Staffoli S. age, gender, cultural background and subspecialty of dentistry practiced in a group of Italian dentists and “Sapienza” University of Rome, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial their general knowledge of clinical and epidemiological sciences, Division of Pediatric Dentistry aspects of Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation. Pediatric Dentistry, chair prof. Antonella Polimeni Methods: Multiple choice questionnaires were distributed Restorative Sciences and Endodontics, chair prof. Gianluca Gambarini to a population sample of 398 dentists belonging to ANDI (Italian Association of Dentists), Bologna section. Aim: To evaluate the performance of a three-dimensions These questionnaires were previously validated and the (3D) imaging software (3D Slicer) developed for data retrieved were compared to previously published medical surgeons, in the 3D rendering of images of data. deciduous teeth made by CBCT. 3D Slicer is an open Results: Response rate was 63.0% (251/398). 19.1% source platform for segmentation, registration and 3D of respondents had a dual MD-DDS degree; dentists visualization of medical imaging data. Slicer started with six years medical training-only represented as a research project between the Surgical Planning 20.7%; Dental Program graduates = 45.4 %, Dental Lab (Harvard) and the CSAIL - Computer Science and Program graduates with 1-2 year Masters degree = Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (MIT). -

Glossary of Periodontal Terms.Pdf

THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PERIODONTOLOGY Glossary of Periodontal Te rms 4th Edition Copyright 200 I by The American Academy of Periodontology Suite 800 737 North Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60611-2690 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without the express written permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-9264699-3-9 The first two editions of this publication were published under the title Glossary of Periodontic Terms as supplements to the Journal of Periodontology. First edition, January 1977 (Volume 48); second edition, November 1986 (Volume 57). The third edition was published under the title Glossary vf Periodontal Terms in 1992. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The fourth edition of the Glossary of Periodontal Terms represents four years of intensive work by many members of the Academy who generously contributed their time and knowledge to its development. This edition incorporates revised definitions of periodontal terms that were introduced at the 1996 World Workshop in Periodontics, as well as at the 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. A review of the classification system from the 1999 Workshop has been included as an Appendix to the Glossary. Particular recognition is given to the members of the Subcommittee to Revise the Glossary of Periodontic Terms (Drs. Robert E. Cohen, Chair; Angelo Mariotti; Michael Rethman; and S. Jerome Zackin) who developed the revised material. Under the direction of Dr. Robert E. Cohen, the Committee on Research, Science and Therapy (Drs. David L. -

A00–B99 Certain Infectious and Parasitic Diseases

1 . Kode Gol. Jenis Penyakit No Title Of Diseases Penyakit Penyakit akibat infeksi & I A00–B99 Certain infectious and parasitic diseases Parasit Neoplasms Keganasan / kanker/tumor II C00–D48 Diseases of the blood and blood-forming Penyakit darah /kelainan III D50–D89 organs and certain disorders involving the darah /keganasan sistem immune mechanism imun Penyakit endokrin & IV E00–E90 Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases metabolik & nutrisi Mental and behavioural disorders Gangguan prilaku & mental V F00–F99 Diseases of the nervous system Penyakit sistem saraf VI G00–G99 Diseases of the eye and anexa Penyakit mata & adnexa VII H00–H59 VIII H60–H95 Diseases of the ear and mastoid process Penyakit telinga & mastoid Penyakit sistem sirkulasi IX I00–I99 Diseases of the circulatory system darah Diseases of the respiratory system Penyakit sistem pernafasan X J00–J99 XI K00–K93 Diseases of the digestive system Penyakit sistem pencernaan Penyakit kulit & jaringan XII L00–L99 Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue subkutan Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and Penyakit sistem otot/rangka XIII M00–M99 connective tissue & jaringan penyambung Penyakit sistem kemih & XIV N00–N99 Diseases of the genitourinary system kelamin Kehamilan, Persalinan & O00–O99 Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium XV nifas Certain conditions originating in the perinatal Periode perinatal XVI P00–P96 period Congenital malformations, deformations and Malformasi kongenital, XVII Q00–Q99 chromosomal abnormalities deformitas & abnormal Symptoms, signs -

Torus Mandibularis: Etiology and Bioarcheological Utility

Volume 19, Number 1, 2006 ISSN 1096-9411 Dental Anthropology A Publication of the Dental Anthropology Association Dental Anthropology Volume 19, Number 1, 2006 Dental Anthropology is the Official Publication of the Dental Anthropology Association. Editor: Edward F. Harris Editorial Board Kurt W. Alt (2004-2009) Richard T. Koritzer (2004-2009) A. M. Haeussler (2004-2009) Helen Liversidge (2004-2009) Tseunehiko Hanihara (2004-2009) Yuji Mizoguchi (2006-2010) Kenneth A. R. Kennedy (2006-2010) Lindsay C. Richard (2006-2010) Jules A. Kieser (2004-2009) Phillip W. Walker (2006-2010) Officers of the Dental Anthropology Association Simon W. Hillson (University College London) President (2006-2008) Brian E. Hemphill (California State University, Bakersfield) President-Elect (2006-2008) Heather H. Edgar (Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, NM) Secretary-Treasurer (2003-2006) Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg (Ohio State University, OH) Past-President (2004-2006) Address for Manuscripts Dr. Edward F. Harris College of Dentistry, University of Tennessee 870 Union Avenue, Memphis, TN 38163 U.S.A. E-mail address: [email protected] Address for Book Reviews Dr. Greg C. Nelson Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon Condon Hall, Eugene, Oregon 97403 U.S.A. E-mail address: [email protected] Published at Craniofacial Biology Laboratory, Department of Orthodontics College of Dentistry, The Health Science Center University of Tennessee, Memphis, TN 38163 U.S.A. The University of Tennessee is an EEO/AA/Title IX/Section 504/ADA employer 1 Torus Mandibularis: Etiology and Bioarcheological Utility Brenna Hassett University College London Institute of Archaeology, London, United Kingdom ABSTRACT: Torus mandibularis is a non-metric trait defined by sample, age, sex, and measures of functional commonly recorded in bioarcheological investigation stress. -

Developmental Anomalies Affecting the Morphology of Teeth – a Review

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal de Periódicos da UNIVILLE (Universidade da Região de Joinville) ISSN: Electronic version: 1984-5685 RSBO. 2015 Jan-Mar;12(1):68-78 Literature Review Article Developmental anomalies affecting the morphology of teeth – a review Ashish Shrestha1 Vinay Marla1 Sushmita Shrestha2 Iccha K Maharjan3 Corresponding author: Ashish Shrestha Department of Oral Histology and Pathology, College of Dental Surgery B. P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences Dharan – Sunsari – Nepal E-mail: [email protected] 1 Department of Oral Histology and Pathology, College of Dental Surgery, B. P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences – Dharan – Nepal. 2 Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, College of Dental Surgery, B. P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences – Dharan – Nepal. 3 Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, College of Dental Surgery, B. P. Koirala Institute of Health Sciences – Dharan – Nepal. Received for publication: May 5, 2014. Accepted for publication: August 12, 2014. Abstract Keywords: developmental Introduction: The development of tooth is a complex process anomaly, diagnostic wherein there is series of interactions between the ectoderm and criteria, tooth ectomesenchyme. The role of genes in determining the shape and morphology. form of a specific tooth has already been defined, the alterations in which can lead to a variety of anomalies in regards to number, size, form, shape, structure, etc. Objective: To review the literature on the developmental anomalies of teeth. Literature review: The developmental anomalies affecting the morphology exists in both deciduous & permanent dentition and shows various forms such as gemination, fusion, concrescence, dilacerations, dens evaginatus, dens invaginatus, enamel pearls, taurodontism or peg laterals. -

A Unique Syndrome of Gemination and External/ Internal Root Resorptions in One Dental Arch: a Case Report

Crimson Publishers Case Report Wings to the Research A Unique Syndrome of Gemination and External/ Internal Root Resorptions in One Dental Arch: A Case Report Pray Nickolas1, Raghavendra Sree2 and Kazemi Reza B3* 1Pediatric Dentistry Resident, UCONN Health School of Dental Medicine, USA 2 ISSN: 2637-7764 Assistant Clinical Professor, UCONN Health School of Dental Medicine, USA 3Associate Professor, UCONN Health School of Dental Medicine, USA Abstract Dental literature, considering a unique syndrome of two distinct developmental disruptions; fusion and or disease in one dental arch was reviewed. gemination teeth and morphological irregularities; external/internal root resorptions caused by trauma The PubMed and Google Scholar citations revealed only one report of fusion and internal resorption in the same arch/tooth. However, the present case report’s dental inquiry revealed a history of a geminated undermaxillary an unusualleft lateral circumstance. incisor tooth The [# 10]clinical in addition and radiograph to a dental analysis trauma of morethese than two 20teeth years revealed ago, where their both teeth [#s 08 & 09] were traumatized. Tooth [# 09] was avulsed and replanted back into dental alveoli *Corresponding author: Kazemi Reza B, enduring involvement with the external/internal root resorptions as well. Patient reported, no other Associate Professor, UCONN Health School of significant past dental history, except routine dental visits and treatments. The clinical and radiographical Dental Medicine, USA wearevaluation, provided findings, as of Falland 2020 diagnosis are also are described. discussed. The proposed treatment plans for management of the unilateral geminated tooth, external/internal root resorptions and clinical problem of severe occlusal Submission: August 08, 2020 Introduction Published: May 03, 2021 Developmental dental disorders and malformed teeth may be due to congenital, inherited, acquired or idiopathic reasons causing anomalies in tooth number, size, shape and structure. -

Prevalence and Characteristics of Talon Cusps in Turkish Population

[Downloaded free from http://www.drjjournal.net on Tuesday, March 08, 2016, IP: 176.102.244.1] Dental Research Journal Original Article Prevalence and characteristics of talon cusps in Turkish population Yeliz Guven1, Yelda Kasimoglu1, Elif Bahar Tuna1, Koray Gencay1, Oya Aktoren1 1Department of Pedodontics, Faculty of Dentistry, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Background: Talon cusp is a rare dental anomaly characterized by a cusp‑like projection, often including the palatal surface of the affected tooth. The aim of the present study was to investigate the prevalence and characteristics of talon cusps in a group of Turkish children. Materials and Methods: The study population consisted of 14,400 subjects who attended the clinics of the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at the Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey . Subjects ranged in age from 1 to 14 years with a mean age of 10.5 ± 2.55 years. Talon cusps were mainly categorized by visual examination according to the classification of Hattabet al. The distribution and frequency of talon cusps were calculated with respect to dentition type, tooth type, talon type, the affected surface, associated dental anomalies, and clinical complications. Statistical analysis included descriptive statistics, frequencies, and crosstabs with Chi‑square analysis. Results: Talon cusps were detected in 49 subjects (26 males and 23 females) of 14,400 (0.34%). A total of 108 teeth showed talon cusps. Distribution of talon cusps according to gender showed no statistically significant differences. The incidence of talon cusps was found to be greater in maxillary lateral incisors (53.7%) than central incisors (29.62%). Regarding the type of talon cusp, Received: April 2015 47.22% of teeth showed a Type III talon cusp, whereas 30.55% of teeth demonstrated a Type II talon Accepted: September 2015 and 22.22% of teeth demonstrated a Type I talon cusp. -

Chalkidiki 2011

PROCEEDINGS OF THE 20TH EUROPEAN CONGRESS OF VETERINARY DENTISTRY, CHALKIDIKI 2011 20th European Congress of Veterinary Dentistry September 1-3, 2011, Chalkidiki, Greece The ECVD local organising committee (Basilis Psychogios, Serafim Papadimitriou, Theodoros Petanides), the EVDS Board, the EVDC Board and all the participants would like to thank the sponsors of the 20th European Congress of Veterinary Dentistry for their financial support, their help and assistance that helped us to make this meeting a success. Diamond sponsor of the EVDS: Long-term partner of the EVDS: 1 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 20TH EUROPEAN CONGRESS OF VETERINARY DENTISTRY, CHALKIDIKI 2011 EUROPEAN VETERINARY DENTAL SOCIETY UK registered Charity (registration number 1128783) Executive Board President: Jan Schreyer Ahornstraße 42 09112 Chemnitz – Germany Phone: +49 (0) 371/304973 Fax: +49 (0) 371/3674574 E-mail: [email protected] President Elect: Gottfried Morgenegg Postfach 62, Dorfstrasse 70 8912 Obfelden – Switzerland Phone: +41 (0) 44 761 4152 Fax: +41 (0) 44 761 9209 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary: Ines Ott Brueder-Grimm-Str. 3 63450 Hanau, Germany Phone : +49 (0) 6181 22492 Fax : +49 (0) 6181 257176 Email : [email protected] Treasurer (and Past president): Pete Haseler 21 Station Road Studley, Warwickshire, B80 7HR, UK Phone: +44 1527 853 304 Fax: +44 1527 853 688 E-mail: [email protected] Immediate Past President: Jerzy Gawor ul.Chlopska 2a 30-806 Kraków - Poland Phone/FAX: +48 12 6588365 E-mail: [email protected] EVDS web site : http.//www.evds.info -

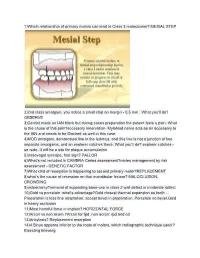

MESIAL STEP 2)2Nd Class Amalgam, You Notice a Small Chip

1)Which relationship of primary molars can lead to Class 3 maloclusion? MESIAL STEP 2)2nd class amalgam, you notice a small chip on margin - 0,5 mm . What you'll do? OBSERVE 3)Dentist made an IAN block but during caries preparation the patient feels a pain. What is the cause of this pain?accessory innervation- Mylohiod nerve acts as an accessory to the IAN and needs to be Blocked as well in this case. 4)MOD amalgam, demarcated line in the isthmus, and this line is not a junction of two separate amalgams, and an explorer catches there. What you'll do? explorer catches - so redo- It will be a site for plaque accumulation 5)Vasovagal syncope, first sign? PALLOR 6)What’s not included in CAMBRA Caries assessment?caries management by risk assessment - GENETIC FACTOR 7)What kind of resorption is happening to second primary molar?REPLACEMENT 8)what’s the cause of recession on that mandibular Incisor? MALOCLUSION, CROWDING 9)osteoctomy?removal of supporting bone-use in class 2 wall defect in moderate defect 10)Gold vs porcelain, what’s advantage?Gold closest thermal expansion as tooth ... Preparation is less fine adaptation. accept bevel in preparation. Porcelain no bevel.Gold in heavy occlusion 11)Most harmful force in implant? HORIZONTAL FORCE 12)Arcon vs non acorn ?Arcon for fpd ,non acron: rpd and cd 13)Ankylosis? Replacement resorption 14)4.Sinus appears inferior to the roots of molars, which radiographic technique used ? Bisecting bitewing 15)Doctor billed insurance couple of procedure when actually there is a global procedure that combines them?UNBUNDLEING 16) Distal occlusion leads to? CLASS 2 17)Child’s BP? –(heart rate)110( 3-4y 120,5-6y 115) 18)Mineralization of the PERM.