Border Field State Park, Who Shared an Incredible Amount of Knowledge and Inspiration with Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relative Genetic Diversity of the Rare and Endangered Agave Shawii Ssp

Received: 17 July 2020 | Revised: 9 December 2020 | Accepted: 14 December 2020 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.7172 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Relative genetic diversity of the rare and endangered Agave shawii ssp. shawii and associated soil microbes within a southern California ecological preserve Jeanne P. Vu1 | Miguel F. Vasquez1 | Zuying Feng1 | Keith Lombardo2 | Sora Haagensen1,3 | Goran Bozinovic1,4 1Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, San Diego, CA, USA Abstract 2Southern California Research Learning Shaw's Agave (Agave shawii ssp. shawii) is an endangered maritime succulent growing Center, National Park Services, San Diego, along the coast of California and northern Baja California. The population inhabiting CA, USA 3University of California San Diego Point Loma Peninsula has a complicated history of transplantation without documen- Extended Studies, La Jolla, CA, USA tation. The low effective population size in California prompted agave transplanting 4 Biological Sciences, University of California from the U.S. Naval Base site (NB) to Cabrillo National Monument (CNM). Since 2008, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA there are no agave sprouts identified on the CNM site, and concerns have been raised Correspondence about the genetic diversity of this population. We sequenced two barcoding loci, rbcL Goran Bozinovic, Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, 3030 Bunker Hill St, and matK, of 27 individual plants from 5 geographically distinct populations, includ- San Diego CA 92109, USA. ing 12 individuals from California (NB and CNM). Phylogenetic analysis revealed the Emails: [email protected]; gbozinovic@ ucsd.edu three US and two Mexican agave populations are closely related and have similar ge- netic variation at the two barcoding regions, suggesting the Point Loma agave popu- Funding information National Park Services (NPS) Pacific West lation is not clonal. -

2020 Pacific Coast Winter Window Survey Results

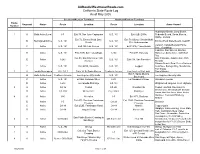

2020 Winter Window Survey for Snowy Plovers on U.S. Pacific Coast with 2013-2020 Results for Comparison. Note: blanks indicate no survey was conducted. REGION SITE OWNER 2017 2018 2019 2020 2020 Date Primary Observer(s) Gray's Harbor Copalis Spit State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum Conner Creek State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Damon Point WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Oyhut Spit WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Ocean Shores to Ocean City 4 10 0 9 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis County Total 4 10 0 9 Pacific Midway Beach Private, State Parks 22 28 58 66 27-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Graveyard Spit Shoalwater Indian Tribe 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum, R. Ashley Leadbetter Point NWR USFWS, State Parks 34 3 15 0 11-Feb W. Ritchie South Long Beach Private 6 0 7 0 10-Feb W. Ritchie Benson Beach State Parks 0 0 0 0 20-Jan W. Ritchie County Total 62 31 80 66 Washington Total 66 41 80 75 Clatsop Fort Stevens State Park (Clatsop Spit) ACOE, OPRD 10 19 21 20-Jan T. Pyle, D. Osis DeLaura Beach OPRD No survey Camp Rilea DOD 0 0 0 No survey Sunset Beach OPRD 0 No survey Del Rio Beach OPRD 0 No survey Necanicum Spit OPRD 0 0 0 20-Jan J. Everett, S. Everett Gearhart Beach OPRD 0 No survey Columbia R-Necanicum R. OPRD No survey County Total 0 10 19 21 Tillamook Nehalem Spit OPRD 0 17 26 19-Jan D. -

4.0 Potential Coastal Receiver Areas

4.0 POTENTIAL COASTAL RECEIVER AREAS The San Diego shoreline, including the beaches, bluffs, bays, and estuaries, is a significant environmental and recreational resource. It is an integral component of the area’s ecosystem and is interconnected with the nearshore ocean environment, coastal lagoons, wetland habitats, and upstream watersheds. The beaches are also a valuable economic resource and key part of the region’s positive image and overall quality of life. The shoreline consists primarily of narrow beaches backed by steep sea cliffs. In present times, the coastline is erosional except for localized and short-lived accretion due to historic nourishment activities. The beaches and cliffs have been eroding for thousands of years caused by ocean waves and rising sea levels which continue to aggravate this erosion. Episodic and site- specific coastal retreat, such as bluff collapse, is inevitable, although some coastal areas have remained stable for many years. In recent times, this erosion has been accelerated by urban development. The natural supply of sand to the region’s beaches has been significantly diminished by flood control structures, dams, siltation basins, removal of sand and gravel through mining operations, harbor construction, increased wave energy since the late 1970s, and the creation of impervious surfaces associated with urbanization and development. With more development, the region’s beaches will continue to lose more sand and suffer increased erosion, thereby reducing, and possibly eliminating their physical, resource and economic benefits. The State of the Coast Report, San Diego Region (USACE 1991) evaluated the natural and man- made coastal processes within the region. This document stated that during the next 50 years, the San Diego region “…is on a collision course. -

Appendix 3 Photographs in Species Accounts

Appendix 3 Photographs in Species Accounts Fulvous Whistling-Duck: Captives at Sea World (A. Mercieca). Pied-billed Grebe: Winter-plumaged bird at Mission Bay Greater White-fronted Goose: Fall migrants at sod farm in the (A. Mercieca). Tijuana River valley, 2002 (A. Mercieca). Horned Grebe: Winter-plumaged bird at San Diego Bay Snow Goose: Wintering flock at the south end of the Salton (A. Mercieca). Sea, Imperial Co. (A. Mercieca). Eared Grebe: Winter-plumaged bird at Mission Bay Ross’s Goose: On San Diego Bay shore at Chula Vista (A. Mercieca). (A. Mercieca). Western Grebe: Pair at Sweetwater Reservoir (A. Mercieca). Brant: On San Diego Bay shore at Chula Vista (A. Mercieca). Clark’s Grebe: At Sweetwater Reservoir (A. Mercieca). Canada Goose: Captive at Sea World (A. Mercieca). Laysan Albatross: In eastern tropical Pacific (P. Unitt). Tundra Swan: Captive at Sea World (A. Mercieca). Black-footed Albatross: Near San Clemente Island Wood Duck: Male at Santee Lakes (A. Mercieca). (R. E. Webster). Gadwall: Male at El Cajon (A. Mercieca). Northern Fulmar: Captive at Sea World (K.W. Fink). Eurasian Wigeon: Captive male at Sea World (K. W. Fink). Pink-footed Shearwater: Near San Clemente Island American Wigeon: Male at Wild Animal Park (A. Mercieca). (B. L. Sullivan). Mallard: Female with ducklings at Santee Lakes (A. Mercieca). Flesh-footed Shearwater: Off Fort Bragg, Mendocino Co., Blue-winged Teal: Male at Famosa Slough (A. Mercieca). 17 August 2002 (B. L. Sullivan). Cinnamon Teal: Pair at Wild Animal Park (A. Mercieca). Buller’s Shearwater: On ocean off California (R. E. Webster). Northern Shoveler: Male at Santee Lakes (A. -

CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: San Diego County, CA 117.06613W

32.812837N 32.804052N 117.559357W 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: San Diego County, CA 117.06613W 91.02 85.10 93.01 85.12 92.01 mi Ave 79.03 85.03 Fer LEGEND Jewell 80.02 85.09 I-805 Nb Off Ra 95.09 S 85.13 Via Bello t 95.11 97.04 Grand G d Av e R e n Fwy 78 e 96.02 SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE s e rillo 93.06 97.03 Baker e 79.05 l 91.01 ab A 87.01 a v C r 80.06 i i v a nd Av r R e o e m R D o Federal American Indian d 79.08 A g a e i i Zion Ave 80.03 s St L'ANSE RES 1880 163 o D Reservation r b n r a Delfern 97.06 79.10 D Am Ingraham hore S Lom S 87.02 Larkin Pl ond d S 77.02 C D t 86 a R r Off-Reservation Trust Land, r d Friars Rd S 93.05 i n T1880 t Fwy r Corona Oriente Rd a 96.04 d Hawaiian Home Land a l R n o l D n Rd l Center June St i io o d s aj r r is av 91.03 79.07 b M 96.03 N W n o 97.05 a g o e R C i i Elsa Rd a d D Ave R s i n y v Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, s a i d S i 88 e n M 92.02 Waring Rd r d a l Alaska Native Village Statistical Area, a Crown Point Dr R P Fairmount s r I o KAW OTSA 5340 d p D d o m Rd e s iu n e tad Tribal Designated Statistical Area r a a s d S l t St S Is o t an Yerba Strand Way s F a e p S r t i io D a s F 5 ro R o ir e g m Santa Dr i P 805 ie o S F i o D el l R u 91.04 d de n State American Indian t B 77.01 90 F d m a a Tama Res 4125 ie rs R C Cam A rdy Ave Reservation y Fria St v 28.01 Ha s s Rio N e i ta d O e Isl c a 55th St L n Hill 35th d e S R n d t a Rd Luc a n 93.04 ille Montezum 76 D State Designated Tribal F 8 20.01 r r o M 89.01 Lumbee STSA 9815 n Statistical -

California Route Log and Finder List

AARoads/WestCoastRoads.com California State Route Log As of May 2005 Southern/Western Terminus Northern/Eastern Terminus Route Segment Status Route Location Route Location Areas Served Number Huntington Beach, Long Beach, 1 A Both Active/Local I-5 Exit 79, San Juan Capistrano U.S. 101 Exit 62B, El Rio Redondo Beach, Santa Monica, Malibu, Oxnard Exit 72, Emma Wood State Exit 79, Mussel Shoals/Mobil B Not Signed/Active U.S. 101 U.S. 101 Emma Wood State Beach, Seacliff Beach Pier Undercrossing Lompoc, Vandenberg Air Force C Active U.S. 101 Exit 132, Las Cruces U.S. 101 Exit 191A, Pismo Beach Base, Guadalupe Cambria, San Simeon, Big Sur, D Active U.S. 101 Exit 203B, San Luis Obispo I-280 Exit 47B, Daly City Monterey, Santa Cruz, Half Moon Bay Exit 50, San Francisco (19th San Francisco, Golden Gate Park, E Active I-280 U.S. 101 Exit 438, San Francisco Avenue) Presidio Stinson Beach, Point Reyes National F Active U.S. 101 Exit 445B, Sausalito U.S. 101 Leggett Seashore, Bodega Bay, Mendocino, Fort Bragg 2 A Locally Maintained I-10, CA 1 Exits 1A-B, Santa Monica Centinela Avenue Los Angeles City Limits Santa Monica Exit 7, Santa Monica B Both Active/Local Centinela Avenue Los Angeles City Limits U.S. 101 Los Angeles, Beverly Hills Boulevard C Active U.S. 101 Exit 4B, Alvarado Street I-210 La Canada-Flintridge Glendale Freeway D Active I-210 La Canada-Flintridge CA 138 Wrightwood, Angeles Crest Highway 3 A Active CA 36 Peanut CA 299 Douglas City Peanut, Hayfork, Douglas City Weaverville, Whiskeytown Shasta- B Active CA 299 Weaverville City Limits -

W • 32°38'47.76”N 117°8'52.44”

public access 32°32’4”N 117°7’22”W • 32°38’47.76”N 117°8’52.44”W • 33°6’14”N 117°19’10”W • 33°22’45”N 117°34’21”W • 33°45’25.07”N 118°14’53.26”W • 33°45’31.13”N 118°20’45.04”W • 33°53’38”N 118°25’0”W • 33°55’17”N 118°24’22”W • 34°23’57”N 119°30’59”W • 34°27’38”N 120°1’27”W • 34°29’24.65”N 120°13’44.56”W • 34°58’1.2”N 120°39’0”W • 35°8’54”N 120°38’53”W • 35°20’50.42”N 120°49’33.31”W • 35°35’1”N 121°7’18”W • 36°18’22.68”N 121°54’5.76”W • 36°22’16.9”N 121°54’6.05”W • 36°31’1.56”N 121°56’33.36”W • 36°58’20”N 121°54’50”W • 36°33’59”N 121°56’48”W • 36°35’5.42”N 121°57’54.36”W • 37°0’42”N 122°11’27”W • 37°10’54”N 122°23’38”W • 37°41’48”N 122°29’57”W • 37°45’34”N 122°30’39”W • 37°46’48”N 122°30’49”W • 37°47’0”N 122°28’0”W • 37°49’30”N 122°19’03”W • 37°49’40”N 122°30’22”W • 37°54’2”N 122°38’40”W • 37°54’34”N 122°41’11”W • 38°3’59.73”N 122°53’3.98”W • 38°18’39.6”N 123°3’57.6”W • 38°22’8.39”N 123°4’25.28”W • 38°23’34.8”N 123°5’40.92”W • 39°13’25”N 123°46’7”W • 39°16’30”N 123°46’0”W • 39°25’48”N 123°25’48”W • 39°29’36”N 123°47’37”W • 39°33’10”N 123°46’1”W • 39°49’57”N 123°51’7”W • 39°55’12”N 123°56’24”W • 40°1’50”N 124°4’23”W • 40°39’29”N 124°12’59”W • 40°45’13.53”N 124°12’54.73”W 41°18’0”N 124°0’0”W • 41°45’21”N 124°12’6”W • 41°52’0”N 124°12’0”W • 41°59’33”N 124°12’36”W Public Access David Horvitz & Ed Steck In late December of 2010 and early Janu- Some articles already had images, in which ary of 2011, I drove the entire California I added mine to them. -

<Insert Month, Day and Year>

Cultural and Paleontological Resources Inventory Report for the East Highline Reservoir Project in El Centro, Imperial County, California Prepared for: Imperial Irrigation District 333 East Barioni Boulevard Imperial, California 92251-0937 Contact: Jessica Lovecchio Prepared by: Matthew DeCarlo, MA; Sarah Siren, MSc; Samantha Murray, MA; and Micah J. Hale, PhD, RPA 605 Third Street Encinitas, California 92024 OCTOBER 2018 Printed on 30% post-consumer recycled material. Cultural and Paleontological Resources Inventory Report for the East Highline Reservoir Project TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page No. ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................... V NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATABASE INFORMATION ..................................VII MANAGEMENT SUMMARY .................................................................................................. IX 1 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION ..............................................................1 1.1 Regulatory Context ................................................................................................. 2 1.1.1 36 CFR 800 and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.... 2 1.1.2 Bureau of Reclamation Cultural Resources Management Policy ............. 12 1.1.3 California Register of Historical Resources (California Public Resources Code, Section 5020 et seq.) ..................................................... 14 1.1.4 Native American Historic Cultural Sites (California Public Resources Code, Section -

General Plan Recreation Element

Recreation Element Recreation Element Recreation Element “Park improvement is among the most important of the undertakings now before the City. It should have the cordial cooperation of all.” San Diego Union editorial on the City Park System, July 6, 1910 Purpose To preserve, protect, acquire, develop, operate, maintain, and enhance public recreation opportunities and facilities throughout the City for all users. Introduction The City of San Diego has over 38,930 acres of park and open space lands that offer a diverse range of recreational opportunities. The City’s parks, open space, trails, and recreation facilities annually serve millions of residents and visitors and play an important role in the physical, mental, social, and environmental health of the City and its residents. Parks can improve the quality of life by strengthening the body and assisting in maintaining physical well-being. Mental and Mission Trails Regional Park social benefits include visual relief from urban development, passive recreational opportunities that refresh the frame of mind and provide opportunities for social interaction, and healthy activities for youth. Park and open space lands benefit the environment by providing habitat for plants and animals, and space for urban runoff to percolate into the soil, while also serving to decrease the effects of urban heat islands. In addition, the City park system supports San Diego’s tourism industry, and enhances the City’s ability to attract and retain businesses. San Diego’s environment, its coastal location, temperate climate, and diverse topography, contribute to creating the City’s first-class recreation and open space system for San Diego’s residents and visitors. -

On the Reconciliation of Biostratigraphy and Strontium Isotope Stratigraphy of Three Southern Californian Plio-Pleistocene Formations

On the reconciliation of biostratigraphy and strontium isotope stratigraphy of three southern Californian Plio-Pleistocene formations Alexandra J. Buczek1, Austin J.W. Hendy2, Melanie J. Hopkins1, and Jocelyn A. Sessa3,† 1 Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West & 79th Street New York, New York 10024, USA 2 Department of Invertebrate Paleontology, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., Los Angeles, California 90007, USA 3 Department of Biodiversity, Earth and Environmental Science, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103, USA ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION 2006; Powell et al., 2009; Squires, 2012; Ven- drasco et al., 2012). Based primarily on regional The San Diego Formation, Pico Forma- The mid-Pliocene warm period (ca 3 Ma; macrofossil and microfossil biostratigraphy, tion, Careaga Sandstone, and Foxen Mud- Jansen et al., 2007) was a time of high global these units are hypothesized to be late Pliocene stone of southern California are thought to temperatures (2 °C to 3 °C above pre-industrial to early Pleistocene in age (Figs. 1 and 3), but no be late Pliocene to early Pleistocene; however, temperatures) and high atmospheric CO2 con- numerical ages exist to confirm this hypothesis. numerical ages have not been determined. centrations (360–400 ppm) (Jansen et al., 2007). Previous age determinations must be revisited Following assessment of diagenetic altera- These climatic conditions, combined with the -

U-M-08-Front 2.Indd

The Tdayicket tripper Avenida Revolución’s A piece by Hugo Lugo Hard Rock Café. at the Tijuana Cultural Center. Taming TIJUTranscendA the sinfulN repA of San Diego’s sister city by checking out the mucha cultura awaiting just across the border The Cultural Center’s IMAX theatre. Los Panchos—home of Tijuana’s best tacos. Shopping at the Plaza Santa Cecilia. Once across, travel by taxi. Average fares are buy a song from a wandering Mariachi or Norteño For a more visceral kick, tear up your PETA about US$7, though establishing the price before band in Plaza Santa Cecilia, then continue on to the membership and follow the trail of red and green you get in the cab is vital. Speaking Spanish will (3) Mercado el Popo (on 2nd between Ave. Niños balloons to the roar and dust of a summer bull- help, but don’t worry if your language skills are Héroes and Ave. Constitutión) for regional cheeses, $ ght, where laughing children toss rosebuds to the rusty—a friendly smile and the name of your des- candies and more exotic items like fried grass- swooping matadors every Sunday a# ernoon from tination will su! ce. hoppers or a Santería love spell from Botánica. May to September at La Plaza de Toros Monu- " e classic tourist experience begins at Avenida But don’t limit yourself to shopping. De$ nitely mental, the “Bullring by the Sea” in Las Playas de TIJUANA IS SYNONYMOUS with wanton indulgence and all-night partying, and for Revolución, the main drag that stretches from the visit the (4) Tijuana Cultural Center (52-664- Tijuana (52-656-613-1656). -

![Otay Water District 2020 UWMP Complete.Pdf[Icon]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6833/otay-water-district-2020-uwmp-complete-pdf-icon-2816833.webp)

Otay Water District 2020 UWMP Complete.Pdf[Icon]

Otay Water District 2020 Urban Water Management Plan Update Prepared by Otay Water District 2554 Sweetwater Springs Boulevard Spring Valley, California 91978 JUNE 2021 1-i Table of Contents Section Page Acronyms and Abbreviations…………………………………......……………………..................….............iv Introduction & Lay Description………………………………………………………………………………………. 1-1 1.1 Changes to the California Urban Water Management Planning Act…….... 1-1 1.2 Senate Bills 610 and 221………………………………………………………………………… 1-2 1.3 Water Conservation Components of UWMP Legislation………………………… 1-2 1.4 Lay Description………………………………………………………………………………………. 1-4 Plan Preparation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2-1 2.1 Basis and Approach for Preparing the UWMP………………………………………… 2-1 2.2 Level of Planning and Compliance……………………………………………………….... 2-1 2.3 Agency Coordination and Outreach………………………………………………………. 2-2 Service Area Characteristics……………………………………………………………………………………………. 3-1 3.1 Service Area Description………………………………………………………………………… 3-1 3.2 Service Area Population…………………………………………………………………………. 3-3 3.3 Climate Data……………………………………………………………………………………….... 3-3 Customer Water Use………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 4-1 4.1 Existing Water Use by Customer Class........................................................ 4-1 4.2 Projected Future Water Demands.............................................................. 4-2 4.3 Service Area Sales and System Losses........................................................ 4-6 4.4 Projected Future Water Conservation Savings..........................................