Eden Journal Articles: Border Field State Park & Its Monument, and San

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining Environmental Injustice

Moore, Danielle 2020 Environmental Studies Thesis Title: America’s Finest City? : Examining Environmental Injustice in San Diego, CA Advisor: Pia Kohler Advisor is Co-author/Adviser Restricted Data Used: None of the above Second Advisor: Release: release now Authenticated User Access (does not apply to released theses): Contains Copyrighted Material: No America’s Finest City?: Examining Environmental Injustice in San Diego, CA by Danielle Moore Pia M. Kohler, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Environmental Studies WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 31, 2020 Moore 1 Acknowledgements First off, I want to give my sincere gratitude to Professor Pia Kohler for her help throughout this whole process. Thank you for giving me constant guidance and support over this time despite all this year’s unique circumstances. I truly appreciate all the invaluable time and assistance you have given me. I also want to thank my second reader Professor Nick Howe for his advice and perspective that made my thesis stronger. Thank you to other members of the Environmental Studies Department that inquired about my thesis and progress throughout the year. I truly appreciate everyone’s encouragement and words of wisdom. Besides the Environmental Studies Department, thank you to all my family members who have supported me during my journey at Williams and beyond. All of you are aware of the challenges that I faced, and I would have not been able to overcome them without your unlimited support. Thank you to all my friends at Williams and at home that have supported me as well. -

Relative Genetic Diversity of the Rare and Endangered Agave Shawii Ssp

Received: 17 July 2020 | Revised: 9 December 2020 | Accepted: 14 December 2020 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.7172 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Relative genetic diversity of the rare and endangered Agave shawii ssp. shawii and associated soil microbes within a southern California ecological preserve Jeanne P. Vu1 | Miguel F. Vasquez1 | Zuying Feng1 | Keith Lombardo2 | Sora Haagensen1,3 | Goran Bozinovic1,4 1Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, San Diego, CA, USA Abstract 2Southern California Research Learning Shaw's Agave (Agave shawii ssp. shawii) is an endangered maritime succulent growing Center, National Park Services, San Diego, along the coast of California and northern Baja California. The population inhabiting CA, USA 3University of California San Diego Point Loma Peninsula has a complicated history of transplantation without documen- Extended Studies, La Jolla, CA, USA tation. The low effective population size in California prompted agave transplanting 4 Biological Sciences, University of California from the U.S. Naval Base site (NB) to Cabrillo National Monument (CNM). Since 2008, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA there are no agave sprouts identified on the CNM site, and concerns have been raised Correspondence about the genetic diversity of this population. We sequenced two barcoding loci, rbcL Goran Bozinovic, Boz Life Science Research and Teaching Institute, 3030 Bunker Hill St, and matK, of 27 individual plants from 5 geographically distinct populations, includ- San Diego CA 92109, USA. ing 12 individuals from California (NB and CNM). Phylogenetic analysis revealed the Emails: [email protected]; gbozinovic@ ucsd.edu three US and two Mexican agave populations are closely related and have similar ge- netic variation at the two barcoding regions, suggesting the Point Loma agave popu- Funding information National Park Services (NPS) Pacific West lation is not clonal. -

Sesd Existing Condition Report.Pdf

EXISTING CONDITIONS REPORT MARCH 2013 Prepared for City of San Diego Prepared by Assisted by Chen/Ryan Associates Keyser Marston Associates, Inc. MW Steele Group Inc. RECON Environmental, Inc. Spurlock Poirier Landscape Architects Ninyo & Moore Page & Turnbull Dexter Wilson Engineering, Inc. Table of Contents i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................1-1 1.1 Community Plan Purpose and Process.......................................................................................................... 1-2 1.2 Regional Location and Planning Boundaries ................................................................................................. 1-3 1.3 Southeastern San Diego Demographic Overview .......................................................................................... 1-6 1.4 Existing Plans and Efforts Underway ............................................................................................................. 1-7 1.5 Report Organization .................................................................................................................................... 1-16 2 LAND USE ...................................................................................................2-1 2.1 Existing Land Use .......................................................................................................................................... 2-2 2.2 Density and Intensity .................................................................................................................................... -

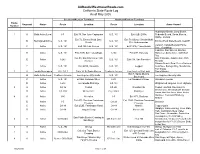

2020 Pacific Coast Winter Window Survey Results

2020 Winter Window Survey for Snowy Plovers on U.S. Pacific Coast with 2013-2020 Results for Comparison. Note: blanks indicate no survey was conducted. REGION SITE OWNER 2017 2018 2019 2020 2020 Date Primary Observer(s) Gray's Harbor Copalis Spit State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum Conner Creek State Parks 0 0 0 0 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Damon Point WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Oyhut Spit WDNR 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum Ocean Shores to Ocean City 4 10 0 9 28-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis County Total 4 10 0 9 Pacific Midway Beach Private, State Parks 22 28 58 66 27-Jan C. Sundstrum, W. Michaelis Graveyard Spit Shoalwater Indian Tribe 0 0 0 0 30-Jan C. Sundstrum, R. Ashley Leadbetter Point NWR USFWS, State Parks 34 3 15 0 11-Feb W. Ritchie South Long Beach Private 6 0 7 0 10-Feb W. Ritchie Benson Beach State Parks 0 0 0 0 20-Jan W. Ritchie County Total 62 31 80 66 Washington Total 66 41 80 75 Clatsop Fort Stevens State Park (Clatsop Spit) ACOE, OPRD 10 19 21 20-Jan T. Pyle, D. Osis DeLaura Beach OPRD No survey Camp Rilea DOD 0 0 0 No survey Sunset Beach OPRD 0 No survey Del Rio Beach OPRD 0 No survey Necanicum Spit OPRD 0 0 0 20-Jan J. Everett, S. Everett Gearhart Beach OPRD 0 No survey Columbia R-Necanicum R. OPRD No survey County Total 0 10 19 21 Tillamook Nehalem Spit OPRD 0 17 26 19-Jan D. -

4.0 Potential Coastal Receiver Areas

4.0 POTENTIAL COASTAL RECEIVER AREAS The San Diego shoreline, including the beaches, bluffs, bays, and estuaries, is a significant environmental and recreational resource. It is an integral component of the area’s ecosystem and is interconnected with the nearshore ocean environment, coastal lagoons, wetland habitats, and upstream watersheds. The beaches are also a valuable economic resource and key part of the region’s positive image and overall quality of life. The shoreline consists primarily of narrow beaches backed by steep sea cliffs. In present times, the coastline is erosional except for localized and short-lived accretion due to historic nourishment activities. The beaches and cliffs have been eroding for thousands of years caused by ocean waves and rising sea levels which continue to aggravate this erosion. Episodic and site- specific coastal retreat, such as bluff collapse, is inevitable, although some coastal areas have remained stable for many years. In recent times, this erosion has been accelerated by urban development. The natural supply of sand to the region’s beaches has been significantly diminished by flood control structures, dams, siltation basins, removal of sand and gravel through mining operations, harbor construction, increased wave energy since the late 1970s, and the creation of impervious surfaces associated with urbanization and development. With more development, the region’s beaches will continue to lose more sand and suffer increased erosion, thereby reducing, and possibly eliminating their physical, resource and economic benefits. The State of the Coast Report, San Diego Region (USACE 1991) evaluated the natural and man- made coastal processes within the region. This document stated that during the next 50 years, the San Diego region “…is on a collision course. -

Appendix 3 Photographs in Species Accounts

Appendix 3 Photographs in Species Accounts Fulvous Whistling-Duck: Captives at Sea World (A. Mercieca). Pied-billed Grebe: Winter-plumaged bird at Mission Bay Greater White-fronted Goose: Fall migrants at sod farm in the (A. Mercieca). Tijuana River valley, 2002 (A. Mercieca). Horned Grebe: Winter-plumaged bird at San Diego Bay Snow Goose: Wintering flock at the south end of the Salton (A. Mercieca). Sea, Imperial Co. (A. Mercieca). Eared Grebe: Winter-plumaged bird at Mission Bay Ross’s Goose: On San Diego Bay shore at Chula Vista (A. Mercieca). (A. Mercieca). Western Grebe: Pair at Sweetwater Reservoir (A. Mercieca). Brant: On San Diego Bay shore at Chula Vista (A. Mercieca). Clark’s Grebe: At Sweetwater Reservoir (A. Mercieca). Canada Goose: Captive at Sea World (A. Mercieca). Laysan Albatross: In eastern tropical Pacific (P. Unitt). Tundra Swan: Captive at Sea World (A. Mercieca). Black-footed Albatross: Near San Clemente Island Wood Duck: Male at Santee Lakes (A. Mercieca). (R. E. Webster). Gadwall: Male at El Cajon (A. Mercieca). Northern Fulmar: Captive at Sea World (K.W. Fink). Eurasian Wigeon: Captive male at Sea World (K. W. Fink). Pink-footed Shearwater: Near San Clemente Island American Wigeon: Male at Wild Animal Park (A. Mercieca). (B. L. Sullivan). Mallard: Female with ducklings at Santee Lakes (A. Mercieca). Flesh-footed Shearwater: Off Fort Bragg, Mendocino Co., Blue-winged Teal: Male at Famosa Slough (A. Mercieca). 17 August 2002 (B. L. Sullivan). Cinnamon Teal: Pair at Wild Animal Park (A. Mercieca). Buller’s Shearwater: On ocean off California (R. E. Webster). Northern Shoveler: Male at Santee Lakes (A. -

Border Field State Park, Who Shared an Incredible Amount of Knowledge and Inspiration with Me

Client: California State Parks Faculty Advisor: Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris A comprehensive project submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Urban and Regional Planning Disclaimer: This report was prepared in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master in Urban and Regional Planning degree in the Department of Urban Planning at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). It was prepared at the direction of the Department and of California State Parks as a planning client. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department, the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, UCLA as a whole, or the client. 2 Acknowledgments UCLA’s Luskin Center for Innovation provided partial support for this project through a Graduate Research Grant. California State Parks, which provided partial support for the research completed in this project. Anne Marie Tipton, Education Coordinator at Border Field State Park, who shared an incredible amount of knowledge and inspiration with me. Jenny Rigby, of The Acorn Group, who introduced me to this project and worked with me every step of the way, providing advice and guidance, pointed me to important sources of information, and gave thorough and thoughtful edits to this document. Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, my faculty advisor for this project, was also my faculty advisor throughout my master’s program. I am so grateful for her advice, guidance, and support over the past two years. My family and friends who encouraged me along the way, and understood when I wasn’t around. And especially to my husband, Charles Thomas, who has been by my side, supporting me every step of the way, and our daughters, Egeria and Emma, who lovingly and patiently were there to cheer me on. -

Figure 1. Regional Location Map

Figure 1. Regional Location Map - 2 - INTRODUCTION SCOPE AND PURPOSE OF THE PLAN The updated San Ysidro Community Plan (Plan) is a comprehensive revision of the original plan adopted in 1974 and includes the urbanized portion of the Tijuana River Valley. The update was authorized at the City Council budget hearings of July 1987 and work on the project began in December of that year. The Planning Department, with the assistance of the San Ysidro Planning and Development Group, has studied San Ysidro’s major issues and challenges and has developed alternative solutions to realize the community’s potential. Included in the Plan is a set of recommendations based upon those alternative solutions to guide the development and the redevelopment of the San Ysidro community. Formal adoption of the revised Plan requires that the Planning Commission and City Council follow the same procedure of holding public hearings as was followed in adopting the original community plan. Adoption of the Plan also requires an amendment of the Progress Guide and General Plan (General Plan) for the City, which will occur at the first regularly scheduled General Plan amendment hearing following adoption of this Plan. Once the Plan is adopted, any amendments, additions or deletions will require that the Planning Commission and City Council follow City Council Policy 600-35 regarding the procedure for Plan amendments. Although this Plan sets forth procedures for implementation, it does not establish new regulations or legislation, nor does it rezone property. The rezoning and design controls recommended in the Plan will be enacted concurrently with Plan adoption. -

CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: San Diego County, CA 117.06613W

32.812837N 32.804052N 117.559357W 2010 CENSUS - CENSUS TRACT REFERENCE MAP: San Diego County, CA 117.06613W 91.02 85.10 93.01 85.12 92.01 mi Ave 79.03 85.03 Fer LEGEND Jewell 80.02 85.09 I-805 Nb Off Ra 95.09 S 85.13 Via Bello t 95.11 97.04 Grand G d Av e R e n Fwy 78 e 96.02 SYMBOL DESCRIPTION SYMBOL LABEL STYLE s e rillo 93.06 97.03 Baker e 79.05 l 91.01 ab A 87.01 a v C r 80.06 i i v a nd Av r R e o e m R D o Federal American Indian d 79.08 A g a e i i Zion Ave 80.03 s St L'ANSE RES 1880 163 o D Reservation r b n r a Delfern 97.06 79.10 D Am Ingraham hore S Lom S 87.02 Larkin Pl ond d S 77.02 C D t 86 a R r Off-Reservation Trust Land, r d Friars Rd S 93.05 i n T1880 t Fwy r Corona Oriente Rd a 96.04 d Hawaiian Home Land a l R n o l D n Rd l Center June St i io o d s aj r r is av 91.03 79.07 b M 96.03 N W n o 97.05 a g o e R C i i Elsa Rd a d D Ave R s i n y v Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area, s a i d S i 88 e n M 92.02 Waring Rd r d a l Alaska Native Village Statistical Area, a Crown Point Dr R P Fairmount s r I o KAW OTSA 5340 d p D d o m Rd e s iu n e tad Tribal Designated Statistical Area r a a s d S l t St S Is o t an Yerba Strand Way s F a e p S r t i io D a s F 5 ro R o ir e g m Santa Dr i P 805 ie o S F i o D el l R u 91.04 d de n State American Indian t B 77.01 90 F d m a a Tama Res 4125 ie rs R C Cam A rdy Ave Reservation y Fria St v 28.01 Ha s s Rio N e i ta d O e Isl c a 55th St L n Hill 35th d e S R n d t a Rd Luc a n 93.04 ille Montezum 76 D State Designated Tribal F 8 20.01 r r o M 89.01 Lumbee STSA 9815 n Statistical -

California Route Log and Finder List

AARoads/WestCoastRoads.com California State Route Log As of May 2005 Southern/Western Terminus Northern/Eastern Terminus Route Segment Status Route Location Route Location Areas Served Number Huntington Beach, Long Beach, 1 A Both Active/Local I-5 Exit 79, San Juan Capistrano U.S. 101 Exit 62B, El Rio Redondo Beach, Santa Monica, Malibu, Oxnard Exit 72, Emma Wood State Exit 79, Mussel Shoals/Mobil B Not Signed/Active U.S. 101 U.S. 101 Emma Wood State Beach, Seacliff Beach Pier Undercrossing Lompoc, Vandenberg Air Force C Active U.S. 101 Exit 132, Las Cruces U.S. 101 Exit 191A, Pismo Beach Base, Guadalupe Cambria, San Simeon, Big Sur, D Active U.S. 101 Exit 203B, San Luis Obispo I-280 Exit 47B, Daly City Monterey, Santa Cruz, Half Moon Bay Exit 50, San Francisco (19th San Francisco, Golden Gate Park, E Active I-280 U.S. 101 Exit 438, San Francisco Avenue) Presidio Stinson Beach, Point Reyes National F Active U.S. 101 Exit 445B, Sausalito U.S. 101 Leggett Seashore, Bodega Bay, Mendocino, Fort Bragg 2 A Locally Maintained I-10, CA 1 Exits 1A-B, Santa Monica Centinela Avenue Los Angeles City Limits Santa Monica Exit 7, Santa Monica B Both Active/Local Centinela Avenue Los Angeles City Limits U.S. 101 Los Angeles, Beverly Hills Boulevard C Active U.S. 101 Exit 4B, Alvarado Street I-210 La Canada-Flintridge Glendale Freeway D Active I-210 La Canada-Flintridge CA 138 Wrightwood, Angeles Crest Highway 3 A Active CA 36 Peanut CA 299 Douglas City Peanut, Hayfork, Douglas City Weaverville, Whiskeytown Shasta- B Active CA 299 Weaverville City Limits -

Regional Resource Directory

San Diego County Regional Resource Directory SAN DIEGO COUNTY OFFICE OF EDUCATION RANDOLPH E. WARD, COUNTY SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS STUDENT SERVICES AND PROGRAMS DIVISION STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES DEPARTMENT FOSTER YOUTH & HOMELESS EDUCATION SERVICES PROGRAM WWW.SDCOE.NET/FYHES Information provided in this resource directory Information provided in this resource directory is public information; listings provided do not is public information; listings provided do not constitute endorsement by the San Diego constitute endorsement by the San Diego County Office of Education. County Office of Education. YOUTH SPECIFIC RESOURCES: TABLE OF CONTENTS TOBACCO, ALCOHOL & DRUGS COUNTY WIDE RESOURCES: 5 Hotlines 5 Alanon/Alateen: (619)296‐2666 Cocaine Anonymous: (858) 268‐9109 Self Help Resources 5 Alcoholics Anonymous: (619)265‐8762 Narcocs Anonymous: (800) 479‐0062 Cal Fresh 5 SD Harm Reducon: (619) 602‐2763 *ask for a teen group Cash Aid 6 CA Smokers Help Line: (800) 7No Bus Medi‐Cal/Den‐Cal 6 Supplemental Security Income (SSI) 7 TRANSITIONAL LIVING PROGRAMS (YOUTH) Alcohol/Drug Services/Recovery 8 SDYS Take Wing: (619) 221‐8610 THP: (760) 453‐2860 Child Welfare Services 9 (Emancipated or 16‐21 yrs old) (Former Foster Youth) Employment/Educaon 9 New Alternaves (NA), Inc: (858) 278‐1137 YMCA Turning Point: (619) 640‐9774 Employment 9 NA Foster Family Agency: (888) 599‐HOME (emancipated or 18 yrs to 21yrs) Educaon 10 Trolley Trestle: (619) 420‐3620 Food 11 (Former & current foster youth) Health 11 Housing 13 TRANSPORTATION Shelters 13 Home Free: -

Municipal Facilities Inventory

* All municipal facilities are considered active. City of San Diego Municipal Facilities Inventory Potential Pollutants Generated1 (N = None, UK = Unknown, UL = Unlikely, L = Likely) Inspect with Heavy Oil & Bacteria/ Department Description Full Address Watershed HA Name HSA Name HSA Number Has NOI WDID Ind/Com LTEA Category1 Metals Organics Grease Sediment Pesticides Nutrients Viruses 3750 JOHN J. MONTGOMERY AIRPORTS MYF/MONTGOMERY FIELD AIRPORT SAN DIEGO RIVER Lower San Diego Mission San Diego 907.11 Yes Yes Airfields UK UK UK UK UK UK N DRIVE, San Diego, CA 9 37I004117 1424 CONTINENTAL STREET, SAN AIRPORTS SDM/BROWN FIELD AIRPORT TIJUANA Tijuana Valley Water Tanks 911.12 Yes Yes Airfields UK UK UK UK UK UK N DIEGO, San Diego, CA 9 37I003024 ENVIRONMENTAL Recycling, Junk Yards, ARIZONA ST. LANDFILL 2781 PERSHING DR, San Diego, CA SAN DIEGO BAY San Diego Mesa Chollas 908.22 No No L L L L UK UK UK SERVICES Scrap Metal ENVIRONMENTAL 8353 MIRAMAR PLACE, San Diego, MIRAMAR PLACE PENASQUITOS Miramar Reservoir Miramar Reservoir 906.10 No Yes Corporate Yards L L L L UK UK UL SERVICES CA ENVIRONMENTAL ADJACENT TO SEAWORLD, San Recycling, Junk Yards, MISSION BAY LANDFILL MISSION BAY Fiesta Island Fiesta Island 906.70 No No L L L L UK UK UK SERVICES Diego, CA Scrap Metal ENVIRONMENTAL 5180 CONVOY STREET, San Diego, Recycling, Junk Yards, NORTH MIRAMAR LANDFILL MISSION BAY Miramar Miramar 906.40 No No L L L L UK UK UK SERVICES CA Scrap Metal ENVIRONMENTAL PARADISE VALLEY RD AND Recycling, Junk Yards, PARADISE HILLS LANDFILL SAN DIEGO BAY National