Arxiv:1808.02848V1 [Stat.AP] 8 Aug 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messiah Notes.Indd

Take One... The Messiah Violin Teacher guidance notes The Messiah Violin is on display in A zoomable image of the violin is available Gallery 39, Music and Tapestry. on our website. Visit www.ashmolean.org/education/ Starting Questions The following questions may be useful as a starting point for thinking about the Messiah violin and developing speaking and listening skills with your class. • What materials do you think this violin is made from? • Why do you think this violin is in a museum? • Where do you think it might come from? • What kind of person do you think would have owned this violin? • Who could have made it? • Does the violin look like it has been played a lot or does it look brand new? • How old do you think the violin could be? • If I told you that nobody is allowed to play this violin do you feel about that? These guidance notes are designed to help you use the Ashmolean’s Messiah violin as a focus for cross-curricular teaching and learning. A visit to the Ashmolean Museum to see your chosen object offers your class the perfect ‘learning outside the classroom’ opportunity. Background Information Italy - a town that was already famous for its master violin makers. The new styles of violins and cellos that The Object he developed were remarkable for their excellent tonal quality and became the basic design for many TThe Messiah violin dates from Stradivari’s ‘golden modern versions of the instruments. period’ of around 1700 - 1725. The violin owes Stradivari’s violins are regarded as the fi nest ever its fame chiefl y to its fresh appearance due to the made. -

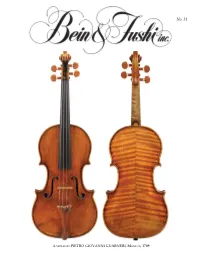

B&F Magazine Issue 31

No. 31 A VIOLIN BY PIETRO GIOVANNI GUARNERI, MANTUA, 1709 superb instruments loaned to them by the Arrisons, gave spectacular performances and received standing ovations. Our profound thanks go to Karen and Clement Arrison for their dedication to preserving our classical music traditions and helping rising stars launch their careers over many years. Our feature is on page 11. Violinist William Hagen Wins Third Prize at the Queen Elisabeth International Dear Friends, Competition With a very productive summer coming to a close, I am Bravo to Bein & Fushi customer delighted to be able to tell you about a few of our recent and dear friend William Hagen for notable sales. The exquisite “Posselt, Philipp” Giuseppe being awarded third prize at the Guarneri del Gesù of 1732 is one of very few instruments Queen Elisabeth Competition in named after women: American virtuoso Ruth Posselt (1911- Belgium. He is the highest ranking 2007) and amateur violinist Renee Philipp of Rotterdam, American winner since 1980. who acquired the violin in 1918. And exceptional violins by Hagen was the second prize winner Camillo Camilli and Santo Serafin along with a marvelous of the Fritz Kreisler International viola bow by Dominique Peccatte are now in the very gifted Music Competition in 2014. He has hands of discerning artists. I am so proud of our sales staff’s Photo: Richard Busath attended the Colburn School where amazing ability to help musicians find their ideal match in an he studied with Robert Lipsett and Juilliardilli d wherehh he was instrument or bow. a student of Itzhak Perlman and Catherine Cho. -

A Violin by Giuseppe Giovanni Battista Guarneri

141 A VIOLIN BY GIUSEPPE GIOVANNI BATTISTA GUARNERI Roger Hargrave, who has also researched and drawn the enclosed poster, discusses an outstanding example of the work of a member of the Guarneri family known as `Joseph Guarneri filius Andrea'. Andrea Guarneri was the first He may never have many details of instruments by of the Guarneri family of violin reached the heights of his Joseph filius at this period recall makers and an apprentice of contemporary, the Amati school, this type of Nicola Amati (he was actually varnish, in combination with registered as living in the house Antonio Stradivarius, but he the freer hand of Joseph, gives of Nicola Amati in 1641). Andrea's does rank as one of the the instruments a visual impact youngest son, whose work is il - greatest makers of all time. never achieved by an Amati or , lustrated here, was called. We should not forget he with the exception of Stradi - Giuseppe. Because several of the sired and trained the great vari, by any other classical Guarneri family bear the same del Gesu' maker before this time. christian names, individuals have traditionally been identified by a It should be said, however, suffix attached to their names. that the varnish of Joseph filius Thus, Giuseppe's brother is known as `Peter Guarneri varies considerably. It is not always of such out - of Mantua' to distinguish him from Giuseppe's son, standing quality the same can be said of Joseph's pro - who is known as `Peter Guarneri of Venice'. duction in general. If I were asked to describe the instruments of a few of the great Cremonese makers Giuseppe himself is called 'Giuseppe Guarneri filius in a single word, I would say that Amatis (all of them) Andrea' or, more simply, `Joseph filius' to distinguish are `refined', Stradivaris are `stately', del Gesus are him from his other son, the illustrious 'Giuseppe `rebellious' and the instruments of Joseph filius An - Guarneri del Gesu'. -

Download Press Release

Borletti-Buitoni Trust Press Release: 21 September 2020 CELEBRATING 20 YEARS Italian Postcards Avie AV2436 Release date 20 November 2020 Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) Italian Serenade in G Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) String Quartet No.1 in G, K.80, Lodi Nimrod Borenstein (1969 -) Cieli d’Italia, Op.88 for string quartet Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) String Sextet in D minor, Op.70, Souvenir de Florence An album of chamber works inspired by the beauty of Italy, including a work specially commissioned for the recording, celebrates the 20th birthday of the renowned Italian ensemble Quartetto di Cremona. It is also, in part, a tribute to the late Italian philanthropist and music lover Franco Buitoni, co-founder with his wife, Ilaria, of the Borletti-Buitoni Trust. A special award was created in his name, which was designated in 2019 for Italian musicians who promote and encourage chamber music at home and throughout the world. The Franco Buitoni Award made this recording possible for the Quartet, which also won a BBT Fellowship award in 2005. With its Italian heritage to the fore, the Quartet chose works by composers who travelled to Italy and were inspired by its breathtaking scenery, rich culture and profound sense of history. The country’s splendours undoubtedly fed the creative spirit of Hugo Wolf, best known as one of the finest eXponents of the art song, including his celebrated Italienishes Liederbuch. The Italian Serenade is his most famous instrumental work, originally written for string quartet, but never performed publicly in Wolf’s lifetime and only published shortly after his death. -

Syrinx (Debussy) Body and Soul (Johnny Green)

Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Hurrian Hymn from Ancient Mesopotamian Spring 2020 Musical Fragment c. 1440 BCE D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Shadow of the Ziggurat Assyrian Hammered Lyre Spring 2020 (Replica) D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Hymn to Horus Replica Ancient Lyre Spring 2020 Based on Trad. Eqyptian Folk Melody D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Roman Banquet Replica Kithara Spring 2020 Orig Composition in Hypophrygian Mode D. H. Tracy Sound of Music How It Works Session 5 Musical Instruments OLLI at Illinois Spring 2020 D. H. Tracy If You Missed a Session…. • PDF’s of previous presentations – Also other handout materials are on the OLLI Course website: http://olli.illinois.edu/downloads/courses/ The Sound of Music Syllabus.pdf References for Sound of Music OLLI Course Spring 2020.pdf Smartphone Apps for Sound of Music.pdf Musical Scale Cheat Sheet.pdf OLLI Musical Scale Slider Tool.pdf SoundOfMusic_1 handout.pdf SoM_2_handout.pdf SoM_3 handout.pdf SoM_4 handout.pdf 2/25/20 Sound of Music 5 6 Course Outline 1. Building Blocks: Some basic concepts 2. Resonance: Building Sounds 3. Hearing and the Ear 4. Musical Scales 5. Musical Instruments 6. Singing and Musical Notation 7. Harmony and Dissonance; Chords 8. Combining the Elements of Music 2/25/20 Sound of Music 5 7 Chicago Symphony Orchestra (2015) 2/25/20 Sound of Music -

The Working Methods of Guarneri Del Gesů and Their Influence Upon His

45 The Working Methods of Guarneri del Gesù and their Influence upon his Stylistic Development Text and Illustrations by Roger Graham Hargrave Please take time to read this warning! Although the greatest care has been taken while compiling this site it almost certainly contains many mistakes. As such its contents should be treated with extreme caution. Neither I nor my fellow contributors can accept responsibility for any losses resulting from information or opin - ions, new or old, which are reproduced here. Some of the ideas and information have already been superseded by subsequent research and de - velopment. (I have attempted to included a bibliography for further information on such pieces) In spite of this I believe that these articles are still of considerable use. For copyright or other practical reasons it has not been possible to reproduce all the illustrations. I have included the text for the series of posters that I created for the Strad magazine. While these posters are all still available, with one exception, they have been reproduced without the original accompanying text. The Labels mentions an early form of Del Gesù label, 98 later re - jected by the Hills as spurious. 99 The strongest evi - Before closing the body of the instrument, Del dence for its existence is found in the earlier Gesù fixed his label on the inside of the back, beneath notebooks of Count Cozio Di Salabue, who mentions the bass soundhole and roughly parallel to the centre four violins by the younger Giuseppe, all labelled and line. The labels which remain in their original posi - dated, from the period 1727 to 1730. -

The Issue of Size: a Glimpse Into the History of the Violoncello Piccolo

Page 1 The Issue of Size: A Glimpse into the History of the Violoncello Piccolo by Johanna Randvere Early Music Department University of the Arts, Sibelius Academy April 2020 Page 2 Abstract The aim of this research is to find out whether, how and why the size, tuning and the number of strings of the cello in the 17th and 18th centuries varied. There are multiple reasons to believe that the instrument we now recognize as a cello has not always been as clearly defined as now. There are written theoretical sources, original survived instruments, iconographical sources and cello music that support the hypothesis that smaller-sized cellos – violoncelli piccoli – were commonly used among string players of Europe in the Baroque era. The musical examples in this paper are based on my own experience as a cellist and viol player. The research is historically informed (HIP) and theoretically based on treatises concerning instruments from the 17th and the 18th centuries as well as articles by colleagues around the world. In the first part of this paper I will concentrate on the history of the cello, possible reasons for its varying dimensions and how the size of the cello affects playing it. Because this article is quite cello-specific, I have included a chapter concerning technical vocabulary in order to make my text more understandable also for those who are not acquainted with string instruments. In applying these findings to the music written for the piccolo, the second part of the article focuses on the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, namely cantatas with obbligato piccolo part, Cello Suite No. -

Secrets of Stradivarius' Unique Violin Sound Revealed, Prof Says 22 January 2009

Secrets Of Stradivarius' unique violin sound revealed, prof says 22 January 2009 Nagyvary obtained minute wood samples from restorers working on Stradivarius and Guarneri instruments ("no easy trick and it took a lot of begging to get them," he adds). The results of the preliminary analysis of these samples, published in "Nature" in 2006, suggested that the wood was brutally treated by some unidentified chemicals. For the present study, the researchers burned the wood slivers to ash, the only way to obtain accurate readings for the chemical elements. They found numerous chemicals in the wood, among them borax, fluorides, chromium and iron salts. Violin "Borax has a long history as a preservative, going back to the ancient Egyptians, who used it in mummification and later as an insecticide," For centuries, violin makers have tried and failed to Nagyvary adds. reproduce the pristine sound of Stradivarius and Guarneri violins, but after 33 years of work put into "The presence of these chemicals all points to the project, a Texas A&M University professor is collaboration between the violin makers and the confident the veil of mystery has now been lifted. local drugstore and druggist at the time. Their probable intent was to treat the wood for Joseph Nagyvary, a professor emeritus of preservation purposes. Both Stradivari and biochemistry, first theorized in 1976 that chemicals Guarneri would have wanted to treat their violins to used on the instruments - not merely the wood and prevent worms from eating away the wood because the construction - are responsible for the distinctive worm infestations were very widespread at that sound of these violins. -

The Strad Magazine

FRESH THINKING WOOD DENSITOMETRY MATERIAL Were the old Cremonese luthiers really using better woods than those available to other makers FACTS in Europe? TERRY BORMAN and BEREND STOEL present a study of density that seems to suggest otherwise Violins await testing on a CT scanner gantry S ALL LUTHIERS ARE WELL AWARE, of Stradivari. To test this conjecture, we set out to compare the business of making an instrument of the the wood employed by the classical Cremonese makers with violin family is fraught with pitfalls. There that used by other makers, during the same time period but are countless ways to ruin the sound of the from various regions across Europe. This would eliminate one fi nished product, starting with possibly the variable – the ageing of the wood – and allow the tracking of Amost fundamental decision of all: what wood to use. In the past geographical and topographical variation. In particular, we 35 years we have seen our knowledge of the available options wanted to investigate the densities of the woods involved, which expand greatly – and as we learn more about the different wood we felt could be the key to unlocking these secrets. choices, it is increasingly hard not to agonise over the decision. What are the characteristics we need as makers? Should we just WHY DENSITY? look for a specifi c grain line spacing, or a good split? Those were The three key properties of wood, from an instrument maker’s the characteristics that makers were once taught to watch out perspective, are density, stiffness (‘Young’s modulus’) and for, and yet results are diffi cult to repeat from instrument to damping (in its simplest terms, a measure of how long an object instrument when using the same pattern – suggesting these are will vibrate after being set in motion). -

Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 Knightsbridge, London

Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 Knightsbridge, London Musical Instruments Monday 12 May 2014 at 12pm Knightsbridge, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services Please see back of catalogue Montpelier Street Director of Department Monday to Friday for Notice to Bidders Knightsbridge Philip Scott 8.30am to 6pm London SW7 1HH +44 (0) 20 7393 3855 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 New bidders must also provide proof www.bonhams.com [email protected] of identity when submitting bids. Illustrations Failure to do this may result in your Viewing Specialist Front cover: Lot 273 & 274 bids not being processed. Friday 9 May Thomas Palmer Back cover: Lot 118 +44 (0) 20 7393 3849 9am to 4.30pm [email protected] IMPORTANT Saturday 10 May INFORMATION 11am to 5pm The United States Government Department Fax has banned the import of ivory Sunday 11 May +44 (0) 20 7393 3820 11am to 5pm Live online bidding is into the USA. Lots containing available for this sale ivory are indicated by the symbol Customer Services Ф printed beside the lot number Bids Please email [email protected] Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm with “Live bidding” in the in this catalogue. +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax subject line 48 hours before To bid via the internet the auction to register for Please register and obtain your this service. please visit www.bonhams.com customer number/ condition report for this auction at Please provide details of the lots [email protected] on which you wish to place bids at least 24 hours prior to the sale. -

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri Del Gesù: a Paper-Chase and a Proposition

Searching for Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù: a paper-chase and a proposition Nicholas Sackman © 2021 During the past 200 years various investigators have laboured to unravel the strands of confusion which have surrounded the identity and life-story of the violin maker known as Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. Early-nineteenth-century commentators – Count Cozio di Salabue, for example – struggled to make sense of the situation through the physical evidence of the instruments they owned, the instruments’ internal labels, and the ‘understanding’ of contemporary restorers, dealers, and players; regrettably, misinformation was often passed from one writer to another, sometimes acquiring elaborations on the way. When research began into Cremonese archives the identity of individuals (together with their dates of birth and death) were sometimes announced as having been securely determined only for subsequent investigations to show that this certainty was illusory, the situation being further complicated by the Italian habit of christening a new- born son with multiple given names (frequently repeating those already given to close relatives) and then one or more of the given names apparently being unused during that new-born’s lifetime. During the early twentieth century misunderstandings were still frequent, and even today uncertainties still remain, with aspects of del Gesù’s chronology rendered opaque through contradictory or no documentation. The following account examines the documentary and physical evidence. ***** NB: During the first decades of the nineteenth century there existed violins with internal labels showing dates from the 1720s and the inscription Joseph Guarnerius Andrea Nepos. The Latin Dictionary compiled by Charlton T Lewis and Charles Short provides copious citations drawn from Classical Latin (as written and spoken during the period when the Roman Empire was at its peak, i.e. -

1002775354-Alcorn.Pdf

3119 A STUDY OF STYLE AND INFLUENCE IN THE EARLY SCHOOLS OF VIOLIN MAKING CIRCA 1540 TO CIRCA 1800 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Allison A. Alcorn, B.Mus. Denton, Texas December, 1987 Alcorn, Allison A., A Study of Style and Influence in the Ear School of Violin Making circa 1540 to circa 1800. Master of Music (Musicology), December 1987, 172 pp., 2 tables, 31 figures, bibliography, 52 titles. Chapter I of this thesis details contemporary historical views on the origins of the violin and its terminology. Chapters II through VI study the methodologies of makers from Italy, the Germanic Countries, the Low Countries, France, and England, and highlights the aspects of these methodologies that show influence from one maker to another. Chapter VII deals with matters of imitation, copying, violin forgery and the differences between these categories. Chapter VIII presents a discussion of the manner in which various violin experts identify the maker of a violin. It briefly discusses a new movement that questions the current methods of authenti- cation, proposing that the dual role of "expert/dealer" does not lend itself to sufficient objectivity. The conclusion suggests that dealers, experts, curators, and musicologists alike must return to placing the first emphasis on the tra- dition of the craft rather than on the individual maker. o Copyright by Allison A. Alcorn TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES.... ............. ........viii LIST OF TABLES. ................ ... x Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . .............. *.. 1 Problems in Descriptive Terminology 3 The Origin of the Violin.......