Globalization and the Washington Consensus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deleuze and Guattari As Dependency Theorists Samuel Weeks Thomas Jefferson University, [email protected]

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons College of Humanities and Sciences Faculty Papers Jefferson College of Humanities and Sciences 2-1-2019 A Politics of Peripheries: Deleuze and Guattari as Dependency Theorists Samuel Weeks Thomas Jefferson University, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/jchsfp Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Weeks, Samuel. "A Politics of Peripheries: Deleuze and Guattari as Dependency Theorists.” Deleuze and Guattari Studies, Volume 13, Issue 1, February 2019, Pages 79-103. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The effeJ rson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The ommonC s is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The effeJ rson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in College of Humanities and Sciences Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Deleuze and Guattari Studies ‘A Politics of Peripheries: Deleuze and Guattari as Dependency Theorists’ Samuel Weeks, M.A., Ph.D. College of Humanities and Sciences Thomas Jefferson University [email protected] This file is the pre-publication version. Here is the citation of the published article: Weeks, Samuel (2019) ‘A Politics of Peripheries: Deleuze and Guattari as Dependency Theorists’, Deleuze and Guattari Studies 13.1, pp. -

Germany's New Security Demographics Military Recruitment in the Era of Population Aging

Demographic Research Monographs Wenke Apt Germany's New Security Demographics Military Recruitment in the Era of Population Aging 123 Demographic Research Monographs A Series of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research Editor-in-chief James W. Vaupel Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock, Germany For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/5521 Wenke Apt Germany’s New Security Demographics Military Recruitment in the Era of Population Aging Wenke Apt ISSN 1613-5520 ISBN 978-94-007-6963-2 ISBN 978-94-007-6964-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-007-6964-9 Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg New York London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013952746 © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifi cally for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. -

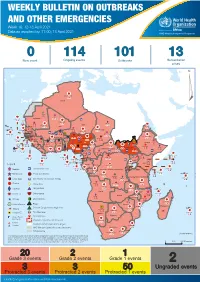

Week 16: 12-18 April 2021

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 16: 12-18 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 18 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 114 101 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 119 642 3 155 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 694 170 Mauritania 7 2 13 070 433 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 129 453 Mali 3 491 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 706 169 Eritrea Cape Verde 39 782 1 091 Chad Senegal 5 074 189 61 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 20 466 191 973 5 Guinea-Bissau 847 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 236 49 242 028 3 370 0 164 233 2 061 Guinea 13 129 154 12 38 397 1 3 712 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 72 0 Ethiopia 540 2 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 61 731 919 52 14 Ghana 5 787 75 Côte d'Ivoire 10 473 114 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 97 17 25 0 21 612 260 45 560 274 91 709 771 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 151 653 2 481 655 2 43 0 119 12 6 1 488 6 4 028 79 12 533 7 259 106 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 066 85 41 378 338 Kenya Legend 7 611 95 Gabon Congo 2 012 73 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 275 35 23 888 325 Measles 21 858 133 Democratic Republic of the Congo 10 084 137 Burundi 3 612 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 28 956 745 235 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 190 0 4875 25 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 24 389 561 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 90 918 1 235 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 941 1 138 862 0 3 815 146 Zambia 133 0 Mozambique -

The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy and the End of the Republic Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE SORROWS OF EMPIRE: MILITARISM, SECRECY AND THE END OF THE REPUBLIC PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chalmers Johnson | 400 pages | 27 Mar 2006 | Verso Books | 9781844675487 | English | London, United Kingdom The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy and the End of the Republic PDF Book The next biggest seller was Russia, selling 17 billion. Trivia About The Sorrows of Em It is not a pretty story. Reminding us of the classic warnings against militarism—from George Washington's farewell address to Dwight Eisenhower's denunciation of the military-industrial complex—Johnson uncovers its roots deep in our past. Dangerous Women 3. Strength of the street: Karachi - Kamran Asdar Ali. Share Tweet. I know, a crazy idea, but stick with me, if only to amuse me. It is here that the book reads with an anti-capitalist tome, which is relevant for the subject of exploitation yet so too would the command economy that helps to fund the military and constrains the populaces of the domestic and foreign people subjugated to rule. Sorrows of Empire, indeed. Oh, yeah, that's why It often has a lot of unnecessary detail, and lacks a clear structure. Johnson often conflates the economic lure of open trade with imperial coercion. Are we heading for a military takeover by the pentagon? Oh, and by the way, just in case you are ever asked. This is likely a reflection of the expansive nature of the history of the US empire. War on the waterfront - Peter Cole. Anybody who questions the concept of American Imperialism can put those to rest by reading this book. -

Democratizing the Global Economy the Role of Civil Society

DEMOCRATIZING THE GLOBAL ECONOMY THE ROLE OF CIVIL SOCIETY 1 Issued June 2004 by the Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL, UK Tel. ++44-24-7657 2533 Fax ++44-24-7657 2548 [email protected] ISBN 0 902683 56 X (English original) ISBN 0 902683 58 6 (Arabic translation by Ola Abou Zeid) ISBN 0 902683 59 4 (French translation by Marc Mousli) ISBN 0 902683 60 8 (Portuguese translation by Sergio Flaksmana and Renato Aguiar) ISBN 0 902683 61 6 (Russian translation by Liliana Proskuryakova) ISBN 0 902683 62 4 (Spanish translation by Rosalba Icaza Garza with Marcelo Saguier) ISBN 0 902683 63 2 (Thai translation by Suntaree Kiatiprajuk) This report was prepared by Jan Aart Scholte of CSGR ([email protected]), with extensive and much-appreciated collaboration from: Ola Abou Zeid, Cairo University ([email protected]) Flávia Braga, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro ([email protected]) Christian Chavagneux, Alternatives Economiques, Paris ([email protected]) Zie Gariyo, Uganda Debt Network, Kampala ([email protected]) Elena Kochkina, Open Society Institute-Russia, Moscow ([email protected]) Kanokrat Lertchoosakul, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok ([email protected]) Liliana Proskuryakova, Europe and Central Asia Region NGO Working Group on the World Bank, St Petersburg ([email protected]) Gauri Sreenivasan, Canadian Council for International Co-operation, Ottawa ([email protected]) Naruemon Thabchumpon, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok ([email protected] or [email protected]) Carlos Vainer, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro ([email protected]) Sincere thanks also go to the several hundred civil society practitioners (listed in Appendix 3) who have contributed a wealth of ideas and experiences to this project. -

New Millennium, New Perspectives UNU Millennium Series

New millennium, new perspectives UNU Millennium Series Series editors: Hans van Ginkel and Ramesh Thakur The UNU Millennium Series examines key international trends for peace, governance, human development, and the environment into the twenty- first century, with particular emphasis upon policy relevant recommenda- tions for the United Nations. The series also contributes to broader aca- demic and policy debate concerning the challenges that are faced at the international level at the turn of the Millennium, and envisions potential for partnerships among states, international organizations, and civil soci- ety actors in collectively addressing these challenges. New millennium, new perspectives: The United Nations, security, and governance Edited by Ramesh Thakur and Edward Newman © The United Nations University, 2000 The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not neces- sarily reflect the views of the United Nations University. The United Nations University 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, 150-8925, Japan Tel: +81-3-3499-2811 Fax: +81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.unu.edu United Nations University Office in North America 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-1462-70, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: +1-212-963-6387 Fax: +1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] Cover design by Joyce C. Weston Printed in the United States of America UNUP-1054 ISBN 92-808-1054-5 Contents Tables and figures . vii 1 Introduction . 1 Ramesh Thakur 2 Security and governance in the new millennium: Observations and syntheses . 7 Edward Newman Security 3 The Security Council in the 1990s: Inconsistent, improvisational, indispensable? . -

Mapping of Child Protection Accountability Mechanisms in Armed Conflict in Africa

1 LIST OF ACRONYMS Save the Children Somalia MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS IN ARMED CONFLICT IN AFRICA SAVE THE CHILDREN 1 MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISMS IN ARMED CONFLICT IN AFRICA ARMED CONFLICT IN MECHANISMS IN ACCOUNTABILITY MAPPING OF CHILD PROTECTION Save the Children Somalia 2 SAVE THE CHILDREN Save the Children is the world’s leading independent organisation for children. Save the Children works in more than 120 countries. We save children’s lives. We fight for their rights. We help them fulfil their potential. 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS Our vision A world in which every child attains the right to survival, protection, development and participation. Our mission To inspire breakthroughs in the way the world treats children and to achieve immediate and lasting change in their lives. We will stay true to our values of accountability, ambition, collaboration, creativity and integrity. Published by: Save the Children International East and Southern Africa Regional Office Regional Programming Unit Protecting Children in Conflict P.O. Box 19423-00202 Nairobi, Kenya Cellphone: +254 711 090 000 [email protected] www.savethechildren.net Save the Children East & Southern Africa Region SaveTheChildren E&SA @ESASavechildren https://www.youtube.com/channel/ UCYafJ7mw4EutPvYSkpnaruQ Project Lead: Anthony Njoroge Technical Lead: Fiona Otieno Reviewers: Simon Kadima, Joram Kibigo, Maryline Njoroge, Alexandra Chege, Mory Camara, Måns Welander, Anta Fall, Liliane Coulibaly, and Rita Kirema. © Save the Children International August 2019 Photos: Save the Children SAVE THE CHILDREN 3 Save the Children is the world’s leading independent organisation for children. Save the Children works in more than 120 countries. -

A Tribute to Giovanni Arrighi

JOURNAL FÜR ENTWICKLUNGSPOLITIK herausgegeben vom Mattersburger Kreis für Entwicklungspolitik an den österreichischen Universitäten vol. XXVII 1–2011 GIOVANNI ARRIGHI: A Global Perspective Schwerpunktredaktion: Amy Austin-Holmes, Stefan Schmalz Inhaltsverzeichnis 4 Amy Austin-Holmes, Stefan Schmalz From Africa to Asia: The Intellectual Trajectory of Giovanni Arrighi 14 Samir Amin A Tribute to Giovanni Arrighi 25 Fortunata Piselli Reflections on Calabria: A Critique of the Concept of ‘Primitive Accumulation’ 44 Çaglar Keyder, Zafer Yenal Agrarian Transformation, Labour Supplies, and Proletarianization Processes in Turkey: A Historical Overview 72 Thomas Ehrlich Reifer Global Inequalities, Alternative Regionalisms and the Future of Socialism 95 Walden Bello China and the Global Economy: The Persistence of Export-Led Growth 113 Rezension 116 Editors of the Special Issue and Authors 119 Impressum Journal für Entwicklungspolitik XXVII 1-2011, S. 14-24 SAMIR AMIN A Tribute to Giovanni Arrighi 1. Giovanni Arrighi: a preeminent analyst of contemporary globalization Born in Italy, died on June 18, 2009 at the age of 71, Giovanni Arrighi was one of the most eminent critical analysts of the contemporary world system. Faced with arrest due to his support of the liberation movement in colonial Rhodesia, Giovanni went on to deepen his analysis of Africa’s dependency during his stay in Tanzania. He continued his work on the contemporary world system at the Fernand Braudel Center of SUNY-Bing- hamton in the United States, which was directed at that time by Immanuel Wallerstein, and then later at John Hopkins University in Baltimore. At the end of 1970, Giovanni Arrighi – along with André Gunder Frank, Immanuel Wallerstein and myself – believed that capitalism had entered a phase of systemic crisis, marked by the fall in growth rates in its dominant cores (with, as a result, the system never again returning to its former rates). -

A Popular Strongman Gains More Power by Joseph Purugganan September 2019

Blickwechsel Gesellscha Umwelt Menschenrechte Armut Politik Entwicklung Demokratie Gerechtigkeit In the Aftermath of the 2019 Philippine Elections: A Popular Strongman Gains More Power By Joseph Purugganan September 2019 The Philippines concluded a high-stakes midterm elections in May 2019, that many consider a critical turning point in our nation’s history. While the Presidency was not on the line, and Rodrigo Duterte himself was not on the ballot, the polls were seen as a referendum on his presidency. Duterte has drawn flak for his deadly ‘War on In midterm elections, voters have historically fa- Drugs’ that has taken the lives of over 5,000 vored candidates backed by a popular incumbent suspects according to official police accounts, and rejected those supported by unpopular ones. but the death toll could be as high as 27,000 ac- In the 2013 midterms for instance, the adminis- cording to the Philippine Commission on Human tration supported by former President Benigno Rights. The administration has also been criti- Aquino III, won 9 out of 12 Senate seats. Like cized for its handling of the maritime conflict Duterte, Aquino had a high satisfaction rating with China in the West Philippine Sea. heading into the midterms. In contrast, a very unpopular Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, with neg- Going into the polls however, Duterte, despite ative net satisfaction ratings, weighed down the all the criticisms at home and abroad, has main- administration ticket. In the Senate race in 2007, tained consistently high popularity and trust the Genuine Opposition coalition was able to se- ratings. The latest survey conducted five months cure eight out of 12 Senate seats, while Arroyo’s ahead of the elections showed the President Team Unity only got two seats and the other two having a 76 percent trust score and an 81 percent slots went to independent candidates. -

International Trends Analysis – Yearbook 2007

Håkan Edström & Åke Wiss (eds.) International InternationalTrends Analysis Trends Analysis Yearbook 2007 Yearbook 2007 HÅKAN EdstrÖM & ÅKE Wiss (eds.) With an introduction to the ART-model ACTORS REGIONS THEMES FOI, Swedish Defence Research Agency, is a mainly assignment-funded agency under the Ministry of Defence. The core activities are research, method and technology development, as well as studies conducted in the interests of Swedish defence and the safety and security of society. The organisation employs approximately 1000 per- sonnel of whom about 800 are scientists. This makes FOI Sweden’s largest research institute. FOI gives its customers access to leading-edge expertise in a large number of fields such as security policy studies, defence and security related analyses, the assessment of various types of threat, systems for control and management of crises, protection against and management of hazardous substances, IT security and the potential offered by new sensors. FOI-R--2361--SE User Report Defence Analysis FOI ISSN 1650-1942 December 2007 Defence Research Agency Phone: +46 8 555 030 00 www.foi.se Division of Defence Analysis Fax: +46 8 555 031 00 FOI-R--2361--SE User report Defence Analysis SE- 164 90 Stockholm ISSN 1650-1942 December 2007 International Trends Analysis – Yearbook 2007 With an introduction to the ART-model Håkan Edström & Åke Wiss (eds.) 3 Titel Omvärldsanalys – Årsbok 2007 Title International Trends Analysis – Yearbook 2007. With an introduction to the ART-model Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--2361--SE Rapporttyp Användarrapport Report Type User Report Sidor/Pages 202 pages Månad/Month December Utgivningsår/Year 2007 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Forskningsområde 2. -

Towards Democratic Globalization: to WTO Or Not to WTO?

Towards Democratic Globalization: To WTO or not to WTO? Jan Nederveen Pieterse No one is calling for an end to trade or trade rules. But what will those rules be, and who will write them? (Lori Wallach, 2004: 71) In his paper on ‘Economic globalization and institutions of global governance’, Keith Griffin (2003) adopts a welcome forward-looking focus. Griffin is committed to symmetric and democratic globalization and presents policies towards implementing this; I will comment on his argument and then focus on the WTO. According to Griffin, ‘greater globalization, not less, is desirable’ (2003: 793). Here the question is of course what kind of globalization or on what terms? In welcoming ‘greater liberalization, not less’ (ibid.: 792) Griffin is on a similar track as Paul Krugman, Jagdish Bhagwati, Megnad Desai and others. In basic terms this is an obvious case. Developing countries lose about US$ 100 billion a year due to export subsidies and trade barriers in developed countries. Tariff barriers against manufactured goods from the developing world are, on average, four times higher than those against products from the industrialized world and the poorest nations face higher tariffs than less poor nations (Oxfam, 2002; World Bank, 2002). ‘Trade not aid’ has long been the guiding motto. But obvious as the case may be, the question again is not ‘trade or liberalization, or not’, but ‘trade and liberalization on what terms?’. Griffin objects to trends towards protectionism, in particular restrictions on the movement of unskilled labour and the regime of intellectual property rights, and proposes ‘to create a rule-based system of global economic govern- ance as it applies to international trade’ (ibid.: 797). -

The Hyperglobalization of Trade and Its Future

Working Paper Series WP 13-6 JULY 2013 The Hyperglobalization of Trade and Its Future Arvind Subramanian and Martin Kessler Abstract Th is paper describes seven salient features of trade integration in the 21st century: Trade integration has been more rapid than ever (hyperglobalization); it is dematerialized, with the growing importance of services trade; it is democratic, because openness has been embraced widely; it is criss-crossing because similar goods and investment fl ows now go from South to North as well as the reverse; it has witnessed the emergence of a mega-trader (China), the fi rst since Imperial Britain; it has involved the proliferation of regional and preferential trade agreements and is on the cusp of mega-region- alism as the world's largest traders pursue such agreements with each other; and it is impeded by the continued existence of high barriers to trade in services. Going forward, the trading system will have to tackle three fundamental challenges: In developed countries, the domestic support for globalization needs to be sustained in the face of economic weakness and the reduced ability to maintain social insurance mechanisms. Second, China has become the world’s largest trader and a major benefi ciary of the current rules of the game. It will be called upon to shoulder more of the responsibilities of maintaining an open system. Th e third challenge will be to prevent the rise of mega-regionalism from leading to discrimi- nation and becoming a source of trade confl icts. We suggest a way forward—including new areas of cooperation such as taxes—to maintain the open multilateral trading system and ensure that it benefi ts all countries.