Urban Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt Market Watch

JANUARY 2017 MARKETWATCH Information from Cartus on Relocation and International Assignment Trends and Practices. EMERGING MARKETS: EGYPT Egypt’s strong links with western countries instead of the Egyptian pound (EGP) due to the latter’s loss in has made it a popular destination for many value. However, the gap between US and Egyptian currency is now beginning to narrow, which means landlords are more multinational organisations wanting a foothold willing to accept payments in EGP. into Africa and the Middle East. Like most emerging markets, Egypt still remains a Cairo. Cairo is the most frequent expatriate destination in Egypt and as such there is a high demand for rental properties. Over challenging location for some international the past 15 years there has been an increase in new compounds assignees with housing and security issues to meet expatriate demand. These are mainly located in New currently highlighted as key areas of focus. Cairo in the east of the city and in 6th of October City to the west. With a large number of international organisations having Key Challenge Areas head offices in 6th of October City and New Cairo, many assignees and their families choose to live in these areas, which Input from Cartus’ Destination Service Provider on the ground in have good access to schools and nearby markets. Other popular Egypt, highlights the following key areas for assignees: neighbourhoods for assignees include Maadi, Zamalek, Dokki, Security Garden City and Rehab City. Housing Lease Conditions. Leases are typically for a minimum of one year, Transportation although bi-annual leases are available for a slightly higher cost. -

669-678 Issn 2077-4613

Middle East Journal of Applied Volume : 09 | Issue :03 |July-Sept.| 2019 Sciences Pages: 669-678 ISSN 2077-4613 Open Museum of Modern Historical Palaces of Cairo, Garden City as A case study Nermin M. Farrag Architecture, Civil & Architectural Engineering Department, Engineering Research Division, National Research Centre, 33 El Behouth St., 12622 Dokki, Giza, Egypt. Received: 30 March 2019 / Accepted 04 July 2019 / Publication date: 20 July 2019 ABSTRACT Tourism comes between the main four sources of national income in Egypt, cultural Tourism is one of the most significant and oldest kinds of tourism in Egypt, and so Egypt needs to create new historic attraction. The research focuses on domestic architecture in Garden City that can be attributed a range of values such as an economic, an aesthetic, a use, a sentimental and a symbolic. This research aims to save our historical palaces in Egypt and realize the economic opportunity for the lowest-income community. The research studies many Garden City palaces and highlights the threats facing these cultural treasures. In the start of 21st century, we have lost a lot of our best historic palaces. One of the solutions that have been put forward for the Garden City is the conversion of some streets in Garden City to be pedestrian streets, the Primary aim to achieve environmentally sustainable development and tourism development for the region. Research methodology is a methodology analytical practical support to reach the goal of research through: (1) monitoring the sources of the current national income in Egypt in general. (2) The current reality of the palaces of Garden City. -

Importers Address Telephone Fax Make(S)

Importers Address Telephone Fax Make(s) Alpha Auto trading Josef tito st. Cairo +20 02-2940330 +20 02-2940600 Citroën cars Amal Foreign Trade Heliopolis, Cairo 11Fakhry Pasha St +20 02-2581847 +20 02-2580573 Lada Artoc Auto - Skoda 2, Aisha Al Taimouria st. Garden city Cairo +20 02-7944172 +20 02-7951622 Skoda Asia Motors Egypt 69, El Nasr Road, New Maadi, Cairo +20 02-5168223 +20 02-5168225 Asia Motors Atic/Arab Trading & 21 Talaat Harb St. Cairo +20 02-3907897 +20 02-3907897 Renault CV Insurance Center of 4, Wadi Al nil st. Mohandessin Cairo +20 02-3034775 +20 02-3468300 Peugeot Development & commerce - CDC - Wagih Abaza Chrysler Egypt 154 Orouba St. Heliopolis Cairo +20 02-4151872 +20 02-4151841 Chrysler Daewoo Corp Dokki, Giza- 18 El-Sawra St. Cairo +20 02-3370015 +20 02-3486381 Daewoo Daimler Chrysler Sofitel Tower, 28 th floor Conish el Nil, +20 02-5263800 +20 02-5263600 Mercedes, Egypt Maadi, Cairo Chrysler Egypt Engineering Shubra, Cairo-11 Terral el-ismailia +20 02-4266484 +20 02-4266485 Piaggio Industries Egyptan Automotive 15, Mourad St. Giza +20 02-5728774 +20 02-5733134 VW, Audi Egyptian Int'l Heliopolice Cairo Ismailia Desert Rd: Airport +20 02-2986582 +20 02-2986593 Jaguar Trading & Tourism / Rolls Royce Jaguar Egypt Ferrari El-Alamia ( Hashim Km 22 First of Cairo - Ismailia road +20 02-2817000 +20 02-5168225 Brouda Kancil bus ) Engineering Daher, Cairo 11 Orman +20 02-5890414 +20 02-5890412 Seat Automotive / SMG Porsche Engineering 89, Tereat Al Zomor Ard Al Lewa +20 02-3255363 +20 02-3255377 Musso, Seat , Automotive Co / Mohandessin Giza Porsche SMG Engineering for Cairo 21/24 Emad El-Din St. -

How to Navigate Egypt's Enduring Human Rights Crisis

How to Navigate Egypt’s Enduring Human Rights Crisis BLUEPRINT FOR U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY January 2016 Human Rights First American ideals. Universal values. On human rights, the United States must be a beacon. Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s a vital national interest. America is strongest when our policies and actions match our values. Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and action organization that challenges America to live up to its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in the struggle for human rights so we press the U.S. government and private companies to respect human rights and the rule of law. When they don’t, we step in to demand reform, accountability and justice. Around the world, we work where we can best harness American influence to secure core freedoms. We know that it is not enough to expose and protest injustice, so we create the political environment and policy solutions necessary to ensure consistent respect for human rights. Whether we are protecting refugees, combating torture, or defending persecuted minorities, we focus not on making a point, but on making a difference. For over 30 years, we’ve built bipartisan coalitions and teamed up with frontline activists and lawyers to tackle issues that demand American leadership. Human Rights First is a nonprofit, nonpartisan international human rights organization based in New York and Washington D.C. To maintain our independence, we accept no government funding. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Egyptian Urban Exigencies: Space, Governance and Structures of Meaning in a Globalising Cairo A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Roberta Duffield Committee in charge: Professor Paul Amar, Chair Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse Assistant Professor Javiera Barandiarán Associate Professor Juan Campo June 2019 The thesis of Roberta Duffield is approved. ____________________________________________ Paul Amar, Committee Chair ____________________________________________ Jan Nederveen Pieterse ____________________________________________ Javiera Barandiarán ____________________________________________ Juan Campo June 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis committee at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose valuable direction, comments and advice informed this work: Professor Paul Amar, Professor Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Professor Javiera Barandiarán and Professor Juan Campo, alongside the rest of the faculty and staff of UCSB’s Global Studies Department. Without their tireless work to promote the field of Global Studies and committed support for their students I would not have been able to complete this degree. I am also eternally grateful for the intellectual camaraderie and unending solidarity of my UCSB colleagues who helped me navigate Californian graduate school and come out the other side: Brett Aho, Amy Fallas, Tina Guirguis, Taylor Horton, Miguel Fuentes Carreño, Lena Köpell, Ashkon Molaei, Asutay Ozmen, Jonas Richter, Eugene Riordan, Luka Šterić, Heather Snay and Leila Zonouzi. I would especially also like to thank my friends in Cairo whose infinite humour, loyalty and love created the best dysfunctional family away from home I could ever ask for and encouraged me to enroll in graduate studies and complete this thesis: Miriam Afifiy, Eman El-Sherbiny, Felix Fallon, Peter Holslin, Emily Hudson, Raïs Jamodien and Thomas Pinney. -

Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report

Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Housing, Utilities and Urban Communities European Investment Bank L’Agence Française de Développement (AFD) Construction Authority for Potable Water & Wastewater CAPW Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project Non-Technical Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) Report Date of issue: May 2020 Consulting Engineering Office Prof. Dr.Moustafa Ashmawy Helwan Wastewater Collection & Treatment Project NTS ESIA Report Non - Technical Summary 1- Introduction In Egypt, the gap between water and sanitation coverage has grown, with access to drinking water reaching 96.6% based on CENSUS 2006 for Egypt overall (99.5% in Greater Cairo and 92.9% in rural areas) and access to sanitation reaching 50.5% (94.7% in Greater Cairo and 24.3% in rural areas) according to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). The main objective of the Project is to contribute to the improvement of the country's wastewater treatment services in one of the major treatment plants in Cairo that has already exceeded its design capacity and to improve the sanitation service level in South of Cairo at Helwan area. The Project for the ‘Expansion and Upgrade of the Arab Abo Sa’ed (Helwan) Wastewater Treatment Plant’ in South Cairo will be implemented in line with the objective of the Egyptian Government to improve the sanitation conditions of Southern Cairo, de-pollute the Al Saff Irrigation Canal and improve the water quality in the canal to suit the agriculture purposes. This project has been identified as a top priority by the Government of Egypt (GoE). The Project will promote efficient and sustainable wastewater treatment in South Cairo and expand the reclaimed agriculture lands by upgrading Helwan Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) from secondary treatment of 550,000 m3/day to advanced treatment as well as expanding the total capacity of the plant to 800,000 m3/day (additional capacity of 250,000 m3/day). -

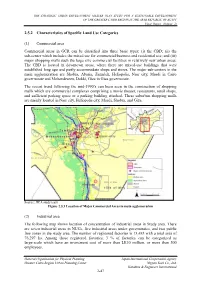

2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial

THE STRATEGIC URBAN DEVELOPMENT MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR A SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE GREATER CAIRO REGION IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT Final Report (Volume 2) 2.5.2 Characteristics of Specific Land Use Categories (1) Commercial area Commercial areas in GCR can be classified into three basic types: (i) the CBD; (ii) the sub-center which includes the mixed use for commercial/business and residential use; and (iii) major shopping malls such the large size commercial facilities in relatively new urban areas. The CBD is located in downtown areas, where there are mixed-use buildings that were established long ago and partly accommodate shops and stores. The major sub-centers in the main agglomeration are Shobra, Abasia, Zamalek, Heliopolis, Nasr city, Maadi in Cairo governorate and Mohandeseen, Dokki, Giza in Giza governorate. The recent trend following the mid-1990’s can been seen in the construction of shopping malls which are commercial complexes comprising a movie theater, restaurants, retail shops, and sufficient parking space or a parking building attached. These suburban shopping malls are mainly located in Nasr city, Heliopolis city, Maadi, Shobra, and Giza. Source: JICA study team Figure 2.5.3 Location of Major Commercial Areas in main agglomeration (2) Industrial area The following map shows location of concentration of industrial areas in Study area. There are seven industrial areas in NUCs, five industrial areas under governorates, and two public free zones in the study area. The number of registered factories is 13,483 with a total area of 76,297 ha. Among those registered factories, 3 % of factories can be categorized as large-scale which have an investment cost of more than LE10 million, or more than 500 employees. -

Directory of Development Organizations

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.A / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

Southeast Asia

Jesus Reigns Ministries - Makati Moonwalk Baptist Church Touch Life Fellowship Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Bangkok, THAILAND Southeast Asia $2,000 $4,000 $3,500 Jesus the Gospel Ministry New Generation Christian Assembly True Worshipers of God Church Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Cebu City, PHILIPPINES Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES $3,700 $1,500 $2,250 Jesus the Great I Am New Life Community Church Unified Vision Christian Community Christian Ministries Metro Cebu City, PHILIPPINES Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES $1,500 $2,800 $3,900 New Life Plantation Universal Evangelical Christian Church Jesus the Word of Life Ministries Four Square Church Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Lae, PAPUA NEW GUINEA $4,000 $3,250 $1,500 Valenzuela Christian Fellowship Jordan River Church Tangerang Pinyahan Christian Church Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Jakarta, INDONESIA Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES $3,500 $2,000 $3,370 Lighthouse Church of Quezon City Restoration of Camp David Church Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Jakarta, INDONESIA $3,000 $2,000 Maranatha International Baptist Church - Tangerang Ekklesia Bethel Church Muntinlupa Jakarta, INDONESIA Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES $4,000 $3,000 Touch Life Fellowship received a $3,500 grant to establish an educational outreach in the Chawala community of Bangkok, THAILAND. Alive in Christ Christian Church Camp David Christian Church Harvester Christian Center Tollef A. Bakke Memorial Award Metro Manila, PHILIPPINES Jakarta, INDONESIA Cebu City, PHILIPPINES $2,750 $5,000 $3,000 Each year the Mustard Seed Foundation designates one grant Ambassador of New Life Camp David Christian Church Heart of Worship Ministry award as a special tribute to the life of one of our founding Fellowship in Christ Metro Jakarta, INDONESIA Davao, PHILIPPINES Board members. -

Helwansouthinterconnectionfin

2 500kV, Interconnection of Helwan South Power Plant - Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan (ARAP) Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Electricity & Renewable Energy Egyptian Electricity Transmission Company 500kV, Electrical Interconnection between Zahraa El Maadi Substation and Helwan South Power Plant Retroactive Review For Already Constructed Towers And Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan (ARAP) For One Tower JULY, 2018 Prepared by: Mohsen E. El-Banna Independent Consultant MOHSEN EL-BANNA 2 3 500kV, Interconnection of Helwan South Power Plant - Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan (ARAP) 500 kV, Electrical Interconnection between Zahraa El Maadi Substation and Helwan South Power Plant Retroactive Review & Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS No. Item Page List of Acronyms and Abbreviation 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Project Description 5 2.1. Components Funded through WB (P100047 - Sokhna Savings) 5 2.2. Overview 6 2.3. Current Implementation and Compensation Status 6 Part One: Retroactive Review of Compensation Status of 7 Towers Completed 7 3. Review Background 7 3.1 Land Type and Use 7 3.2 Potential Impacts on the Use of Land 7 3.3 Type of Settlement and Compensation 8 Part Two: Compensation Plan for the One Remaining Tower 9 4. Action Plan and Entitlement Matrix for the One Remaining Tower 9 5. Grievance Redress and Consultation 9 Annex 1: List of Affected Persons 10 Annex 2: Minutes of Land Transfer to an Association Member & Translation 11 Annex 3: Land Type and Use 13 Annex 4: Minutes of Assessment and Valuation -

State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Geography Geography 2015 State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt Christine E. Smith University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Christine E., "State Violence, Mobility and Everyday Life in Cairo, Egypt" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Geography. 34. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/geography_etds/34 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Geography at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Geography by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

World Bank Urban Transport Strategy Review Reportbird-Eng1.Doc Edition 3 – Nov

Public Disclosure Authorized Edition Date Purpose of edition / revision 1 July 2000 Creation of document – DRAFT – Version française 2 Sept. 2000 Final document– French version 3 Nov. 2000 Final document – English version EDITION : 3 Name Date Signature Public Disclosure Authorized Written by : Hubert METGE Verified by : Alice AVENEL Validated by Hubert METGE It is the responsibility of the recipient of this document to destroy the previous edition or its relevant copies WORLD BANK URBAN TRANSPORT Public Disclosure Authorized STRATEGY REVIEW THE CASE OF CAIRO EGYPT Public Disclosure Authorized Ref: 3018/SYS-PLT/CAI/709-00 World bank urban transport strategy review Reportbird-Eng1.doc Edition 3 – Nov. 2000 Page 1/82 The case of Cairo – Egypt WORLD BANK URBAN TRANSPORT STRATEGY REVIEW THE CASE OF CAIRO EGYPT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Ref: 3018/SYS-PLT/CAI/709-00 World bank urban transport strategy review Reportbird-Eng1.doc Edition 3 – Nov. 2000 Page 2/82 The case of Cairo – Egypt EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 A) INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................4 B) THE TRANSPORT POLICY SINCE 1970..................................................................................................4 C) CONSEQUENCES OF THE TRANSPORT POLICY ON MODE SPLIT.............................................................6 D) TRANSPORT USE AND USER CATEGORIES .............................................................................................7 E) TRANSPORT