IMMORTEL by Franz‐Olivier GIESBERT (75%) Published by Editions FLAMMARION ©2007 (37.5%)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Results FY 2019/2020

Annual results FY 2019/2020 Operating margin rate at 31%, increasing significantly compared with previous fiscal years Continued decrease in overheads : new drop of €14 M compared with 2018/2019 overheads, which were already €7 M lower than the previous fiscal year Net result of €(95) M, mainly due to non-recurring items linked to the restructuring : exceptional result of €(64) M including €(60) M with no cash impact Finalization of the financial restructuring with the completion after closing of the share capital increases reserved for the Vine and Falcon funds for €193 M Saint-Denis, 29 July 2020 – EuropaCorp, one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, film producer and distributor, reports its annual consolidated income, which ended on 31 March 2020, as approved by the Board of Directors at its meeting on 28 July 2020. Presentation IFRS 5* Profit & Loss – € million 31 March 2019 31 March 2020 Var. 31 March 2019 31 March 2020 Var. Revenue 150,0 69,8 -80,2 148,7 69,8 -78,9 Cost of sales -121,6 -48,3 73,3 -121,4 -48,3 73,1 Operating margin 28,4 21,4 -6,9 27,3 21,4 -5,8 % of revenue 19% 31% 18% 31% Operating income -79,0 -59,1 19,9 -71,2 -59,1 12,1 % of revenue -53% -85% -48% -85% 0 Net Income -109,9 -95,1 14,8 -109,9 -95,1 14,8 % of revenue -73% -136% -74% -136% * To be compliant with IFRS 5, the activity related to the exploitation of the catalog Roissy Films, sold in March 2019, has been restated within the consolidated FY 2018/19 for a better comparison. -

BORSALINO » 1970, De Jacques Deray, Avec Alain Delon, Jean-Paul 1 Belmondo

« BORSALINO » 1970, de Jacques Deray, avec Alain Delon, Jean-paul 1 Belmondo. Affiche de Ferracci. 60/90 « LA VACHE ET LE PRISONNIER » 1962, de Henri Verneuil, avec Fernandel 2 Affichette de M.Gourdon. 40/70 « DEMAIN EST UN AUTRE JOUR » 1951, de Leonide Moguy, avec Pier Angeli 3 Affichette de A.Ciriello. 40/70 « L’ARDENTE GITANE» 1956, de Nicholas Ray, avec Cornel Wilde, Jane Russel 4 Affiche de Bertrand -Columbia Films- 80/120 «UNE ESPECE DE GARCE » 1960, de Sidney Lumet, avec Sophia Loren, Tab Hunter. Affiche 5 de Roger Soubie 60/90 « DEUX OU TROIS CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D’ELLE» 1967, de Jean Luc Godard, avec Marina Vlady. Affichette de 6 Ferracci 120/160 «SANS PITIE» 1948, de Alberto Lattuada, avec Carla Del Poggio, John Kitzmille 7 Affiche de A.Ciriello - Lux Films- 80/120 « FERNANDEL » 1947, film de A.Toe Dessin de G.Eric 8 Les Films Roger Richebé 80/120 «LE RETOUR DE MONTE-CRISTO» 1946, de Henry Levin, avec Louis Hayward, Barbara Britton 9 Affiche de H.F. -Columbia Films- 140/180 «BOAT PEOPLE » (Passeport pour l’Enfer) 1982, de Ann Hui 10 Affichette de Roland Topor 60/90 «UN HOMME ET UNE FEMME» 1966, de Claude Lelouch, avec Anouk Aimée, Jean-Louis Trintignant 11 Affichette les Films13 80/120 «LE BOSSU DE ROME » 1960, de Carlo Lizzani, avec Gérard Blain, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Anna Maria Ferrero 12 Affiche de Grinsson 60/90 «LES CHEVALIERS TEUTONIQUES » 1961, de Alexandre Ford 13 Affiche de Jean Mascii -Athos Films- 40/70 «A TOUT CASSER» 1968, de John Berry, avec Eddie Constantine, Johnny Halliday, 14 Catherine Allegret. -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

12 Big Names from World Cinema in Conversation with Marrakech Audiences

The 18th edition of the Marrakech International Film Festival runs from 29 November to 7 December 2019 12 BIG NAMES FROM WORLD CINEMA IN CONVERSATION WITH MARRAKECH AUDIENCES Rabat, 14 November 2019. The “Conversation with” section is one of the highlights of the Marrakech International Film Festival and returns during the 18th edition for some fascinating exchanges with some of those who create the magic of cinema around the world. As its name suggests, “Conversation with” is a forum for free-flowing discussion with some of the great names in international filmmaking. These sessions are free and open to all: industry professionals, journalists, and the general public. During last year’s festival, the launch of this new section was a huge hit with Moroccan and internatiojnal film lovers. More than 3,000 people attended seven conversations with some legendary names of the big screen, offering some intense moments with artists, who generously shared their vision and their cinematic techniques and delivered some dazzling demonstrations and fascinating anecdotes to an audience of cinephiles. After the success of the previous edition, the Festival is recreating the experience and expanding from seven to 11 conversations at this year’s event. Once again, some of the biggest names in international filmmaking have confirmed their participation at this major FIFM event. They include US director, actor, producer, and all-around legend Robert Redford, along with Academy Award-winning French actor Marion Cotillard. Multi-award-winning Palestinian director Elia Suleiman will also be in attendance, along with independent British producer Jeremy Thomas (The Last Emperor, Only Lovers Left Alive) and celebrated US actor Harvey Keitel, star of some of the biggest hits in cinema history including Thelma and Louise, The Piano, and Pulp Fiction. -

25Th Anniversary

25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture 25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award Arts Patronage Montblanc de la Culture 25th Anniversary Arts Patronage Award 1992 25th Anniversary Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award 2016 Anniversary 2016 CONTENT MONTBLANC DE LA CULTURE ARTS PATRONAGE AWARD 25th Anniversary — Preface 04 / 05 The Montblanc de la Culture Arts Patronage Award 06 / 09 Red Carpet Moments 10 / 11 25 YEARS OF PATRONAGE Patron of Arts — 2016 Peggy Guggenheim 12 / 23 2015 Luciano Pavarotti 24 / 33 2014 Henry E. Steinway 34 / 43 2013 Ludovico Sforza – Duke of Milan 44 / 53 2012 Joseph II 54 / 63 2011 Gaius Maecenas 64 / 73 2010 Elizabeth I 74 / 83 2009 Max von Oppenheim 84 / 93 2 2008 François I 94 / 103 3 2007 Alexander von Humboldt 104 / 113 2006 Sir Henry Tate 114 / 123 2005 Pope Julius II 124 / 133 2004 J. Pierpont Morgan 134 / 143 2003 Nicolaus Copernicus 144 / 153 2002 Andrew Carnegie 154 / 163 2001 Marquise de Pompadour 164 / 173 2000 Karl der Grosse, Hommage à Charlemagne 174 / 183 1999 Friedrich II the Great 184 / 193 1998 Alexander the Great 194 / 203 1997 Peter I the Great and Catherine II the Great 204 / 217 1996 Semiramis 218 / 227 1995 The Prince Regent 228 / 235 1994 Louis XIV 236 / 243 1993 Octavian 244 / 251 1992 Lorenzo de Medici 252 / 259 IMPRINT — Imprint 260 / 264 Content Anniversary Preface 2016 This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Montblanc Cultural Foundation: an occasion to acknowledge considerable achievements, while recognising the challenges that lie ahead. Since its inception in 1992, through its various yet interrelated programmes, the Foundation continues to appreciate the significant role that art can play in instigating key shifts, and at times, ruptures, in our perception of and engagement with the cultural, social and political conditions of our times. -

Movies July & August

ENTERTAINMENT Pick your blockbuster! Who better to decide which movies are included in our inflight Language Selection entertainment programme than our passengers? Every month, you get to pick the blockbusters shown on English (EN), French (FR), German (DE), Dutch (NL), Italian (IT), Spanish (ES), Movies July & August Available in Business Class & Economy Class our long haul flights. Simply go to our Facebook page and cast your votes!facebook.com/brusselsairlines Portuguese (PT), Dutch subtitles (NL), English subtitles (EN) ˜ ACTION ˜ Oblivion Jack the Giant Slayer I Don’t Know The Hangover Part II ˜ DRAMA ˜ Hugo Mama Africa Ice Age: Dawn Ever After: PG PG R 13 13 PG NR A Good Day to Die Hard 125mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 114mins (2012) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL How She Does It 102 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 42 120mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL 90 mins (2011) EN, FR Of The Dinosaurs A Cinderella Story R PG PG PG PG 97 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Tom Cruise, Morgan Freeman Ewan McGregor, Ian McShane 13 96 mins (2011) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Bradley Cooper, Ed Helms 13 128 mins (2013) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT, NL Ben Kingsley, Asa Butterfield Miriam Makeba 94 mins (2009) EN, FR, NL, DE, ES, IT 13 121 mins (1998) EN, FR, DE, ES, IT, PT Bruce Willis, Jai Courtney Sarah Jessica Parker, Pierce Brosnan Chadwick Boseman, Harrison Ford Ray Romano, Denis Leary Drew Barrymore, Anjelica Huston JULY FROM JULY FROM FROM JULY ONLY AUGUST ONLY AUGUST AUGUST ONLY From Russia With Love Tomorrow Never Dies Percy -

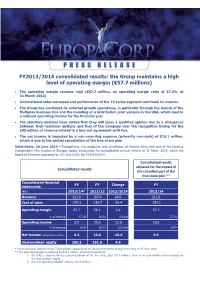

FY2013/2014 Consolidated Results: the Group Maintains a High Level of Operating Margin (€57.7 Millions)

FY2013/2014 consolidated results: the Group maintains a high level of operating margin (€57.7 millions) The operating margin remains high (€57.7 million, an operating margin ratio of 27.3% at 31 March 2014) International sales increased and performance of the TV series segment continued to improve The Group has continued its external growth operations, in particular through the launch of the Multiplex business line and the founding of a distribution joint venture in the USA, which lead to a reduced operating income for the financial year The statutory auditors have stated that they will issue a qualified opinion due to a divergence between their technical analysis and that of the Company over the recognition timing for the $45 million of revenue related to a buy-out agreement with Fox. The net income is impacted by a non-recurring expense (primarily non-cash) of €10.1 million, which is due to the partial cancellation of the free share plan Saint-Denis, 26 June 2014 – EuropaCorp, the producer and distributor of feature films and one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, today announces its consolidated annual results at 31 March 2014, which the Board of Directors approved on 25 June 2014, for FY2013/2014. Consolidated results adjusted for the impact of Consolidated results the cancelled part of the free share plan ** Consolidated financial FY FY Change FY statements (€m) 2013/14* 2012/13 2013/2014 2013/14 Revenue 211.8 185.8 26.0 211,8 Cost of sales -154.1 -129.7 -24.4 -154.1 Operating margin 57.7 56.1 1.6 57.7 % of revenue -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

The Phenomenological Aesthetics of the French Action Film

Les Sensations fortes: The phenomenological aesthetics of the French action film DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alexander Roesch Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Flinn, Advisor Patrick Bray Dana Renga Copyrighted by Matthew Alexander Roesch 2017 Abstract This dissertation treats les sensations fortes, or “thrills”, that can be accessed through the experience of viewing a French action film. Throughout the last few decades, French cinema has produced an increasing number of “genre” films, a trend that is remarked by the appearance of more generic variety and the increased labeling of these films – as generic variety – in France. Regardless of the critical or even public support for these projects, these films engage in a spectatorial experience that is unique to the action genre. But how do these films accomplish their experiential phenomenology? Starting with the appearance of Luc Besson in the 1980s, and following with the increased hybrid mixing of the genre with other popular genres, as well as the recurrence of sequels in the 2000s and 2010s, action films portray a growing emphasis on the importance of the film experience and its relation to everyday life. Rather than being direct copies of Hollywood or Hong Kong action cinema, French films are uniquely sensational based on their spectacular visuals, their narrative tendencies, and their presentation of the corporeal form. Relying on a phenomenological examination of the action film filtered through the philosophical texts of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Mikel Dufrenne, and Jean- Luc Marion, in this dissertation I show that French action cinema is pre-eminently concerned with the thrill that comes from the experience, and less concerned with a ii political or ideological commentary on the state of French culture or cinema. -

Creating a Superheroine: a Rhetorical Analysis of the X-Men Comic Books

CREATING A SUPERHEROINE: A RHETORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE X-MEN COMIC BOOKS by Tonya R. Powers A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: Communication West Texas A&M University Canyon, Texas August, 2016 Approved: __________________________________________________________ [Chair, Thesis Committee] [Date] __________________________________________________________ [Member, Thesis Committee] [Date] __________________________________________________________ [Member, Thesis Committee] [Date] ____________________________________________________ [Head, Major Department] [Date] ____________________________________________________ [Dean, Fine Arts and Humanities] [Date] ____________________________________________________ [Dean, Graduate School] [Date] ii ABSTRACT This thesis is a rhetorical analysis of a two-year X-Men comic book publication that features an entirely female cast. This research was conducted using Kenneth Burke’s theory of terministic screens to evaluate how the authors and artists created the comic books. Sonja Foss’s description of cluster criticism is used to determine key terms in the series and how they were contributed to the creation of characters. I also used visual rhetoric to understand how comic book structure and conventions impacted the visual creation of superheroines. The results indicate that while these superheroines are multi- dimensional characters, they are still created within a male standard of what constitutes a hero. The female characters in the series point to an awareness of diversity in the comic book universe. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my thesis committee chair, Dr. Hanson, for being supportive of me within the last year. Your guidance and pushes in the right direction has made the completion of this thesis possible. You make me understand the kind of educator I wish to be. You would always reply to my late-night emails as soon as you could in the morning. -

Luc Besson B.1959 Le Grand Bleu 1988

Cinéma du Look Spring 2021 Luc Besson b.1959 Le Grand Bleu 1988 The Big Blue: Film From Time Out: https://www.timeout.com/movies/the-big-blue Time Out says The action centres on the rivalry between free-divers Barr and Reno - they dive deep without an aqualung - which begins when they are little boys. The first time you see someone plunging into alien blackness is exciting, but the novelty soon wears off. The first half-hour is the best part of the movie. Going through her usual kooky routine, Arquette plays a New York insurance agent who encounters Barr in Peru, and is captivated by his wide- eyed innocence (which others might describe as bovine stupidity). Her sole purpose seems to be to reassure the audience that there is nothing funny going on between best buddies Barr, who talks to dolphins, and Reno, a macho mother's boy (a performance of much comic credibility). The ending is the worst part of the movie: Barr rejects the pregnant Arquette in favour of going under one last time to become a dolphin-man. Such bathos reeks of cod-Camus. What lies in between is a series of CinemaScopic swathes of blue seas and white cliffs. Besson's film is exactly like his hero: very pretty but very silly. Details Release details Rated: 15 Duration: 119 mins Cast and crew Director: Luc Besson Screenwriter: Luc Besson, Robert Garland, Marilyn Goldin, Jacques Mayol, Marc Perrier Cast: Rosanna Arquette, Jean-Marc Barr, Jean Reno, Paul Shenar, Sergio Castellitto, Jean Bouise, Griffin Dunne Luc Besson Filmography as Director Thirty years ago, Le Grand Bleu (The Big Blue) shook the Croisette Article sourced from Festival de Cannes: https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/72- editions/retrospective/2018/actualites/articles/thirty-years-ago-le-grand-bleu-the-big-blue-shook-the-croisette# In 1988, the Festival de Cannes opened to Le Grand Bleu (The Big Blue) by the young Luc Besson. -

Liste Alphabétique Des DVD Du Club Vidéo De La Bibliothèque

Liste alphabétique des DVD du club vidéo de la bibliothèque Merci à nos donateurs : Fonds de développement du collège Édouard-Montpetit (FDCEM) Librairie coopérative Édouard-Montpetit Formation continue – ÉNA Conseil de vie étudiante (CVE) – ÉNA septembre 2013 A 791.4372F251sd 2 fast 2 furious / directed by John Singleton A 791.4372 D487pd 2 Frogs dans l'Ouest [enregistrement vidéo] = 2 Frogs in the West / réalisation, Dany Papineau. A 791.4372 T845hd Les 3 p'tits cochons [enregistrement vidéo] = The 3 little pigs / réalisation, Patrick Huard . A 791.4372 F216asd Les 4 fantastiques et le surfer d'argent [enregistrement vidéo] = Fantastic 4. Rise of the silver surfer / réalisation, Tim Story. A 791.4372 Z587fd 007 Quantum [enregistrement vidéo] = Quantum of solace / réalisation, Marc Forster. A 791.4372 H911od 8 femmes [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, François Ozon. A 791.4372E34hd 8 Mile / directed by Curtis Hanson A 791.4372N714nd 9/11 / directed by James Hanlon, Gédéon Naudet, Jules Naudet A 791.4372 D619pd 10 1/2 [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Daniel Grou (Podz). A 791.4372O59bd 11'09''01-September 11 / produit par Alain Brigand A 791.4372T447wd 13 going on 30 / directed by Gary Winick A 791.4372 Q7fd 15 février 1839 [enregistrement vidéo] / scénario et réalisation, Pierre Falardeau. A 791.4372 S625dd 16 rues [enregistrement vidéo] = 16 blocks / réalisation, Richard Donner. A 791.4372D619sd 18 ans après / scénario et réalisation, Coline Serreau A 791.4372V784ed 20 h 17, rue Darling / scénario et réalisation, Bernard Émond A 791.4372T971gad 21 grams / directed by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu ©Cégep Édouard-Montpetit – Bibliothèque de l’École nationale d'aérotechnique - Mise à jour : 30 septembre 2013 Page 1 A 791.4372 T971Ld 21 Jump Street [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller.