Elimination of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV in Democratic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

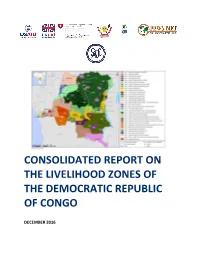

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

Musebe Artisanal Mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo

Gold baseline study one: Musebe artisanal mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo Gregory Mthembu-Salter, Phuzumoya Consulting About the OECD The OECD is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. About the OECD Due Diligence Guidance The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Due Diligence Guidance) provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is for use by any company potentially sourcing minerals or metals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. It is one of the only international frameworks available to help companies meet their due diligence reporting requirements. About this study This gold baseline study is the first of five studies intended to identify and assess potential traceable “conflict-free” supply chains of artisanally-mined Congolese gold and to identify the challenges to implementation of supply chain due diligence. The study was carried out in Musebe, Haut Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. This study served as background material for the 7th ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in Paris on 26-28 May 2014. It was prepared by Gregory Mthembu-Salter of Phuzumoya Consulting, working as a consultant for the OECD Secretariat. -

Health Action in Crises Highlights No 193 – 28 January to 3 February 2008

Health Action in Crises Highlights No 193 – 28 January to 3 February 2008 Each week, the World Health Organization Health Action in Crises in Geneva produces information highlights on critical health-related activities in countries where there are humanitarian crises. Drawing on the various WHO programmes, contributions cover activities from field and country offices and the support provided by WHO regional offices and headquarters. The mandate of the WHO departments specifically concerned with Emergency and Humanitarian Action in Crises is to increase the effectiveness of the WHO contribution to crisis preparedness and response, transition and recovery. This note, which is not exhaustive, is designed for internal use and does not reflect any official position of the WHO Secretariat. CHAD Assessments and Events • Fighting is ongoing in Ndjamena. Refugees are crossing into adjacent Cameroon. All UN non-essential staff have been evacuated. • In Abeche, the situation is calm but very tense and all non-essential staff are ready for evacuation. Adre is reportedly under attack. • Overall, 47 cases of meningitis and four deaths were notified between 8 October and 27 January. The latest case was reported last week in Farchana camp near Adré. So far, no district has reached the epidemic threshold. Case confirmation remains a problem as lumbar punctures are not systematic. • Since 1 January, 1300 cases of acute respiratory syndrome have been reported in the east. The number of cases notified in Oure Cassoni camp has risen from 162 between 14 and 20 January to 449 between 21 and 27 January. • From 1 December to 13 January, 73 cases of whooping cough were reported in the resident communities surrounding Gaga camp. -

Mecanisme De Referencement

EN CAS DE VIOLENCE SEXUELLE, VOUS POUVEZ VOUS ORIENTEZ AUX SERVICES CONFIDENTIELLES SUIVANTES : RACONTER A QUELQU’UN CE QUI EST ARRIVE ET DEMANDER DE L’AIDE La/e survivant(e) raconte ce qui lui est arrivé à sa famille, à un ami ou à un membre de la communauté; cette personne accompagne la/e survivant(e) au La/e survivant(e) rapporte elle-même ce qui lui est arrivé à un prestataire de services « point d’entrée » psychosocial ou de santé OPTION 1 : Appeler la ligne d’urgence 122 OPTION 2 : Orientez-vous vers les acteurs suivants REPONSE IMMEDIATE Le prestataire de services doit fournir un environnement sûr et bienveillant à la/e survivant(e) et respecter ses souhaits ainsi que le principe de confidentialité ; demander quels sont ses besoins immédiats ; lui prodiguer des informations claires et honnêtes sur les services disponibles. Si la/e survivant(e) est d'accord et le demande, se procurer son consentement éclairé et procéder aux référencements ; l’accompagner pour l’aider à avoir accès aux services. Point d’entrée médicale/de santé Hôpitaux/Structures permanentes : Province du Haut Katanga ZS Lubumbashi Point d’entrée pour le soutien psychosocial CS KIMBEIMBE, Camps militaire de KIMBEIMBE, route Likasi, Tel : 0810405630 Ville de Lubumbashi ZS KAMPEMBA Division provinciale du Genre, avenue des chutes en face de la Division de Transport, HGR Abricotiers, avenue des Abricotiers coin avenue des plaines, Q/ Bel Air, Bureau 5, Centre ville de Lubumbashi. Tel : 081 7369487, +243811697227 Tel : 0842062911 AFEMDECO, avenue des pommiers, Q/Bel Air, C/KAMPEMBA, Tel : 081 0405630 ZS RUASHI EASD : n°55, Rue 2, C/ KATUBA, Ville de Lubumbashi. -

An Inventory of Fish Species at the Urban Markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

FISHERIES AND HIV/AIDS IN AFRICA: INVESTING IN SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS PROJECT REPORT | 1983 An inventory of fi sh species at the urban markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Mujinga, W. • Lwamba, J. • Mutala, S. • Hüsken, S.M.C. • Reducing poverty and hunger by improving fisheries and aquaculture www.worldfi shcenter.org An inventory of fish species at the urban markets of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Mujinga, W., Lwamba, J., Mutala, S. et Hüsken, S.M.C. Translation by Prof. A. Ngosa November 2009 Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions This report was produced under the Regional Programme “Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions” by the WorldFish Center and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), with financial assistance from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This publication should be cited as: Mujinga, W., Lwamba, J., Mutala, S. and Hüsken, S.M.C. (2009). An inventory of fish species at the urban markets in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Regional Programme Fisheries and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Investing in Sustainable Solutions. The WorldFish Center. Project Report 1983. Authors’ affiliations: W. Mujinga : University of Lubumbashi, Clinique Universitaire. J. Lwamba : University of Lubumbashi, Clinique Universitaire. S. Mutala: The WorldFish Center DRC S.M.C. Hüsken: The WorldFish Center Zambia National Library of Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Cover design: Vizual Solution © 2010 The WorldFish Center All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational or non-profit purposes without permission of, but with acknowledgment to the author(s) and The WorldFish Center. -

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO (DRC) INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) – QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2020 Quarter One: October 1 – December 31, 2019

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) – QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2020 Quarter One: October 1 – December 31, 2019 This publication was produced by IGA under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. Program Title: Integrated Governance Activity (IGA) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID DRC Contract Number: AID-660-C-17-00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Date of Publication: January 30, 2020 This publication was produced by IGA under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 2 ACTIVITY OVERVIEW / SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 SUMMARY OF RESULTS TO DATE 6 EVALUATION / ASSESSMENT STATUS AND/OR PLANS 12 ACTIVITY IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS 14 PROGRESS NARRATIVE 14 INTEGRATION OF CROSSCUTTING ISSUES AND USAID FORWARD PRIORITIES 33 GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT 33 YOUTH ENGAGEMENT 36 LOCAL CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT 37 INTEGRATION AND COLLABORATION 37 SUSTAINABILITY 38 STAKEHOLDER PARTICIPATION AND INVOLVEMENT 41 MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATIVE ISSUES 55 SUBMITTED DELIVERABLES 55 PROVINCIAL OFFICES 55 MONITORING, EVALUATION, AND LEARNING 55 AMELP/PIRS 55 CHANGE LOG DATA 56 SPECIAL EVENTS FOR NEXT QUARTER 57 HOW USAID IGA HAS ADDRESSED A/COR COMMENTS FROM THE LAST QUARTERLY OR SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT 58 ANNEXES 59 ANNEX A. -

Province Du Katanga Profil Resume Pauvrete Et Conditions De Vie Des Menages

Programme des Nations Unies pour le Développement Unité de lutte contre la pauvreté RDC PROVINCE DU KATANGA PROFIL RESUME PAUVRETE ET CONDITIONS DE VIE DES MENAGES Mars 2009 PROVINCE DU KATANGA Sommaire Province Katanga Superficie 496.877 km2 Population en 2005 8,7 millions Avant-propos..............................................................3 Densité 18 hab/km² 1 – La province de Katanga en un clin d’œil..............4 Nombre de districts 5 2 – La pauvreté au Katanga.......................................6 Nombre de villes 3 3 – L’éducation.........................................................10 Nombre de territoires 22 4 – Le développement socio-économique des Nombre de cités 27 femmes.....................................................................11 Nb de communes 12 5 – La malnutrition et la mortalité infantile ...............12 Nb de quartiers 43 6 – La santé maternelle............................................13 Nombre de groupements 968 7 – Le sida et le paludisme ......................................14 Routes urbaines 969 km 8 – L’habitat, l’eau et l’assainissement ....................15 Routes nationales 4.637 km 9 – Le développement communautaire et l’appui des Routes d’intérêt provincial 679 km Partenaires Techniques Financiers (PTF) ...............16 Réseau ferroviaire 2.530 km Gestion de la province Gouvernement Provincial Nb de ministres provinciaux 10 Nb de députés provinciaux 103 - 2 – PROVINCE DU KATANGA Avant-propos Le présent rapport présente une analyse succincte des conditions de vie des ménages du -

Katanga - Contraintes D'accès Et F ZS Kansimba H K a B O N G O Kayabala Zones De Santé, 16 Octobre 2018

RN Kyofwe 33 ZS Ankoro R E P U B L I Q U E D E M O C R AT I Q U E D U C O N G O ZS Manono T A N G A N Y I K A Kiluba Province du Haut - Katanga - Contraintes d'accès et f ZS Kansimba h K A B O N G O Kayabala Zones de Santé, 16 Octobre 2018 Echelle Nominale: 580.000 au format A0 ! Kabonge KABUMBULU ! Kabongo Nganye \! Capitale Nationale #0í Bac - Ordre de Marche ZS KinkonNodnj amotorisé Réserve Naturelle!h ZS Kabongo ZS Mulongo ZS Moba ! H Plan d'eau K Mayombo \ Chef lieu de Province #0í Bac - Panne Réparable Moto-Velo/ 2 roues a M O B A Kipetwe b ! ! al Mutoto I Kalaba Kabwela o ! ! ! ! Badia Fontière Internationale - M ! Ville de taille Majeure #0Hí Bac - Panne Définitive Vehicule 4x4 <3.5 MT ! ! Pande ! al Kasongo a e u Lyapenda f ! Kilongo m i b Mulongo k a u ! Lubika ! ZS Kiyambi L Ville de taille Moyenne 0#í Bac Privé Camion léger <10 MT MULONGO h Gwena Kabongo M A L E M B A - N K U L U ! ! Manda !\ Chef lieu de Territoire #0í Bac Disparu Camion lourd <20 MT M A N O N O Kasimike ! ! ý Pont détruit Nondo Localité Remorque >20 MT Mwanza Museka (!o Aéroport International ÿ Pont en bon état Non specifié ! Kapela R ! P Katemesha ZS Lwamba 6 L 2 ! u ! ! Aéroport Domestique û Pont en projet / réhabilitation Voie ferrée 9 Mwenge k Lusanange Katanti o Luvua u m ! ! o Kasongo b Kaulu ! i ! Mutiti ! Piste û Pont avec restriction Limite Internationale Kisola Mafuta ZS Songa ! Bempe !h Kabanza ! ! i KABALA Katumba h s H ý Limite de Province ! li ! ! Hélipad Pont en état non connu u ( Kasumato l Mboko i 3 K Kizabi o 3 ! ! Kasumpa N ZS Mukanga -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Since the Beginning of the Year

Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 08 @UNICEF/Tremeauu © UNICEF/Tremeau Reporting Period: August 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 15,000,000 • Four provinces alone account for 90% of cases of Cholera (12,803 children in need of suspected cases), namely North Kivu, South Kivu, Tanganyika and humanitarian assistance Haut-Katanga.14,153 suspected cases, of which 201 deaths, have been (OCHA, Revised reported across the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the beginning of the year. Humanitarian Response • In South Kivu province, UNICEF continues to face continuous Plan 2020, June 2020) challenges to provide humanitarian assistance to people displaced due to conflicts in Mikenge, Minembwe and Bijombo (Haut Plateaux). 25,600,000 Security and logistical constraints are important and limit the access of humanitarian actors. people in need • 57,499 people affected by humanitarian crises in Ituri and North-Kivu (OCHA, Revised HRP 2020) provinces have been provided life-saving emergency packages in NFI/Shelter through UNICEF’s Rapid Response (UniRR). 5,500,000 st • As of 30 August, 109 confirmed cases of Ebola, of which 48 deaths, IDPs (OCHA,Revised HRP have been reported as a result of the DRC’s 11th Ebola outbreak in 2020*) Mbandaka, Equateur province. UNICEF continues to provide a multi- sectoral response in the affected health zones 14,153 cases of cholera reported UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status since January (Ministry of Health) 35% UNICEF Appeal 2020 11% US$ 318 million 56% 17% Funding Status (in US$) 25% Funds 18% received in 2020 88% 28.4M Carry- forwar 34% d 39.7M 12% Fundin 10% g Gap $233.9 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% M 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 318 million to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

DRC INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) Annual Report - FY2020

DRC INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) Annual Report - FY2020 This publication was produced by the Integrated Governance Activity under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. Program Title: Integrated Governance Activity (IGA) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID DRC Contract Number: AID-660-C-17-00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Date of Publication: October 30, 2020 This publication was produced by the Integrated Governance Activity under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 2 ACTIVITY OVERVIEW/SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 ACTIVITY IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS 6 INTEGRATION OF CROSSCUTTING ISSUES AND USAID FORWARD PRIORITIES 33 GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT 33 YOUTH ENGAGEMENT 39 LOCAL CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT 41 SUSTAINABILITY 45 ENVIRONMENTAL COMPLIANCE 46 MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATIVE ISSUES 46 MONITORING, EVALUATION, AND LEARNING 48 INDICATORS 48 EVALUATION/ASSESSMENT STATUS AND/OR PLANS 59 CHALLENGES & LESSONS LEARNED 62 CHALLENGES 62 LESSONS LEARNED 62 ANNEXES 63 ANNEX A. COMMUNICATION AND OUTREACH MESSAGES 63 ANNEX B. -

Mayi Baridi Mine, Tanganyika, Katanga by MMR Baseline Audit Report. Executive Summary

BASELINE AUDITS OF MINING COMPANIES IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO TO THE CTC-STANDARD SET Mayi Baridi Mine, Tanganyika, Katanga by MMR Baseline Audit Report - Executive Summary - Compiled by: Dr. Michael Priester (Mining Consultant, independent auditor) Projekt-Consult GmbH Lärchenstr. 12 61118 Bad Vilbel Germany Tel.: +49 (0) 6101 - 509712 Fax: +49 (0) 6101 - 509729 mail: [email protected] URL: www.projekt-consult.de A project of: DRC Ministry of Mines and BGR Contact: Ministère des Mines de la RDC Genevieve Kizekele, Coordonatrice Commission de Certification (COCERTI) Phone: + 243 81 50 43 720 Mail: genekize2yahoo.fr BGR Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources Geozentrum Hannover Stilleweg 2 30655 Hannover Uwe Naeher BGR Kinshasa, DR Congo Mobile: +243-81-562 4953 Email: [email protected] Antje Hagemann Geozentrum Hannover, Germany Phone:+49 511 643 2338 Email: [email protected] Dr. Bali Barume BGR Bukavu, DR Congo Phone : + 243 81 37 56 097 Email: [email protected] Date: April 2012 BASELINE AUDIT OF MINING COMPANIES IN DRC FOR CTC-CERTIFICATION: Mayi Baridi, Kalemie, Tanganyika, Katanga by MMR – Executive Summary - 2 Table of Content Acronyms ................................................................................................................. 3 Audited company (information as provided with the TOR) ........................................ 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 4 Methodology -

(DRC) INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) – QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2020 Quarter Two: January 1 – March 31, 2020

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO (DRC) INTEGRATED GOVERNANCE ACTIVITY (IGA) – QUARTERLY REPORT FY 2020 Quarter Two: January 1 – March 31, 2020 This publication was produced by IGA under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. Program Title: Integrated Governance Activity (IGA) Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID DRC Contract Number: AID-660-C-17-00001 Contractor: DAI Global, LLC Date of Publication: April 30, 2020 This publication was produced by IGA under Contract No. AID-660-C-17-00001 at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. Government. CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 2 ACTIVITY OVERVIEW / SUMMARY 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 SUMMARY OF RESULTS TO DATE 5 EVALUATION / ASSESSMENT STATUS AND/OR PLANS 10 ACTIVITY IMPLEMENTATION PROGRESS 12 PROGRESS NARRATIVE 12 OBJECTIVE 1: STRENGTHEN CAPACITY OF SELECT GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS TO FULFILL MANDATES 12 OBJECTIVE 2: TARGETED SUBNATIONAL ENTITIES COLLABORATE WITH CITIZENS FOR MORE