Democratic Republic of the Congo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Reports Children in Need of Humanitarian Assistance Its First COVID-19 Confirmed Case

ef Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Situation Report No. 03 © UNICEF/UN0231603/Herrmann Reporting Period: March 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers 9,100,000 • 10 March, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) reports children in need of humanitarian assistance its first COVID-19 confirmed case. As of 31 March 2020, 109 confirmed cases have been recorded, of which 9 deaths and 3 (OCHA, HNO 2020) recovered patients have been reported. During the reporting period, the virus has affected the province of Kinshasa and North Kivu 15,600,000 people in need • In addition to UNICEF’s Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) (OCHA, HNO 2020) 2020 appeal of $262 million, UNICEF’s COVID-19 response plan has a funding appeal of $58 million to support UNICEF’s response 5,010,000 in WASH/Infection Prevention and Control, risk communication, and community engagement. UNICEF’s response to COVID-19 Internally displaced people can be found on the following link (HNO 2020) 6,297 • During the reporting period, 26,789 in cholera-prone zones and cases of cholera reported other epidemic-affected areas benefiting from prevention and since January response WASH packages (Ministry of Health) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status UNICEF Appeal 2020 9% US$ 262 million 11% 21% Funding Status (in US$) 15% Funds Carry- received forward, 10% $5.5 M $28.8M 10% 49% 21% 15% Funding gap, 3% $229.3M 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF appeals for US$ 262M to sustain the provision of humanitarian services for women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). -

IMCK Newsletter 17.3.Pages

INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIEN DU KASAI !1 OFINSTITUT MEDICAL!5 CHRETIEN DU KASAI B.P. 205 KANANGA B.P. 205 KANANGA INSTITUT MEDICAL CHRETIENREPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU DUKASAI CONGO REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Christian Medical Institute Hôpitalof – theEcole d’infirmiers Kasai – Ecole de laborantins - Serving – Service de santé communautairein Central - Service d’ophtalmologie Congo Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage Hôpital – Ecole d’infirmiers – Ecole de laborantins – Service de santé communautaire - Service d’ophtalmologie E-mail : [email protected] Service dentaire – Centre d’études et de recyclage B. P. 205 Kananga, Republic Democratic du Congo ; Email: [email protected] E-mail : [email protected] 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category 2. Find a way to channel a greater percentage of donations back into that unpopular category of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them where A Periodic Newsletter operational needs are Issuethe most desperate. No. 41 But ifJanuary you cannot (and - thatMarch is understandable, 2017 of “undesignated” gifts so that we can have the flexibility to apply them whereA considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider operational needs are the most desperate. But if you cannot (and that is understandable, designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational considering all the news stories one sees about mismanaged funds), then consider The current conflict in the Kasai has needs.I askedFor example the new: Specify IMCK money Administrator, for medicines and Kastin medical Katawa, supplies; Specifyto describe money designating gifts carefully to those things that are at the core of IMCK’s operational added new suffering and danger. -

Introduction Generale

P a g e | 1 INTRODUCTION GENERALE 0.1. Problématique Le présent mémoire porte sur les logotypes et la signification : Analyse de la dénotation et de la connotation des logotypes des banques Trust Merchant Bank (TMB) et Rawbank. En effet, Sperber1 dit qu’il n’y a rien de plus banal que la communication, car les êtres humains sont par nature des êtres communiquant par la parole, le geste, l’écrit, l’habillement et voire le silence, etc. La célèbre école de Palo Alto le dit tout haut aussi: on ne peut pas ne pas communiquer, tout est communication2. La communication, nous la pratiquons tous les jours sans y penser (mais également en y pensant) et généralement avec un succès assez impressionnant, même si parfois nous sommes confrontés à ses limites et à ses échecs. La communication demeure l’élément fondamental et complexe de la vie sociale qui rend possible l’interaction des personnes et dont la caractéristique essentielle est, selon Daniel Lagache3, la réciprocité. Elle est ce par quoi une personne influence une autre et en est influencée, car elle n’est pas indépendante des effets de son action. Morin affirme même que la communication a plusieurs fonctions : l’information, la connaissance, l’explication et la compréhension. Toutefois, pour lui, le problème central dans la communication humaine est celui de la compréhension, car on communique pour comprendre et se comprendre4. Raison pour laquelle, les chercheurs en matière de communication, surtout de notre ère, époque marquée par l’accroissement des entreprises dans la plupart des secteurs de la vie sociale, se trouvent confronté à de nouvelles problématiques qui sont autant d’enjeux pour améliorer la communication. -

DRC Consolidated Zoning Report

CONSOLIDATED REPORT ON THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DECEMBER 2016 Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Livelihoods zoning ....................................................................................................................7 1.2 Implementation of the livelihood zoning ...................................................................................8 2. RURAL LIVELIHOODS IN DRC - AN OVERVIEW .................................................................. 11 2.1 The geographical context ........................................................................................................ 11 2.2 The shared context of the livelihood zones ............................................................................. 14 2.3 Food security questions ......................................................................................................... 16 3. SUMMARY DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LIVELIHOOD ZONES .................................................... 18 CD01 COPPERBELT AND MARGINAL AGRICULTURE ....................................................................... 18 CD01: Seasonal calendar .................................................................................................................... -

Kalemie L'oubliee Kalemie the Forgotten Mwiba Lodge, Le Safari Version Luxe Mexico Insolite Not a Stranger in a Familiar La

JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N° 20 TRIMESTRIEL N° 20 5 YEARS ANNIVERSARY 5 ANS DÉJÀ LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE TRAVEL in AFRICA LE VOYAGE EN AFRIQUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE 2018 N°20 • JUILLET-AOUT-SEPTEMBRE HAMAJI MAGAZINE MEXICO INSOLITE Secret Mexico GRAND ANGLE MWIBA LODGE, LE SAFARI VERSION LUXE Mwiba Lodge, luxury safari at its most sumptuous VOYAGE NOT A STRANGER KALEMIE L’OUBLIEE IN A FAMILIAR LAND KALEMIE THE FORGOTTEN Par Sarah Waiswa Sur une plage du Tanganyika, l’ancienne Albertville — On the beach of Tanganyika, the old Albertville 1 | HAMAJI JUILLET N°20AOÛT SEPTEMBRE 2018 EDITOR’S NEWS 6 EDITO 7 CONTRIBUTEURS 8 CONTRIBUTORS OUR WORLD 12 ICONIC SPOT BY THE TRUST MERCHANT BANK OUT OF AFRICA 14 MWIBA LODGE : LE SAFARI DE LUXE À SON SUMMUM LUXURY SAFARI AT ITS MOST SUMPTUOUS ZOOM ECO ÉCONOMIE / ECONOMY TAUX D’INTÉRÊTS / INTEREST RATES AFRICA RDC 24 Taux d’intérêt moyen des prêts — Average loan interest rates, % KALEMIE L'OUBLIÉE — THE FORGOTTEN Taux d’intérêt moyen des dépôts d’épargne — Average interest TANZANIE - 428,8 30 % rates on saving deposits, % TANZANIA AT A GLANCE BALANCE DU COMPTE COURANT EN MILLION US$ 20 % CURRENT ACCOUNT AFRICA 34 A CHAQUE NUMERO HAMAJI MAGAZINE VOUS PROPOSE UN COUP D’OEIL BALANCE, MILLION US$ SUR L’ECONOMIE D’UN PAYS EN AFRIQUE — IN EVERY ISSUE HAMAJI MAGAZINE OFFERS 250 YOU A GLANCE AT AN AFRICAN COUNTRY’S ECONOMY 10 % TRENDY ACCRA, LA CAPITALE DU GHANA 0 SOURCE SOCIAL ECONOMICS OF TANZANIE 2016 -250 -500 0 DENSITÉ DE POPULATION PAR RÉGION / POPULATION DENSITY PER REGION 1996 -

Concordant Ages for the Giant Kipushi Base Metal Deposit (DR Congo) from Direct Rb–Sr and Re–Os Dating of Sulfides

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Miner Deposita (2007) 42:791–797 DOI 10.1007/s00126-007-0158-y LETTER Concordant ages for the giant Kipushi base metal deposit (DR Congo) from direct Rb–Sr and Re–Os dating of sulfides Jens Schneider & Frank Melcher & Michael Brauns Received: 30 May 2007 /Accepted: 27 June 2007 / Published online: 24 July 2007 # Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract We report concordant ages of 451.1±6.0 and (upper) crust. The concordant Re–Os and Rb–Sr ages 450.5±3.4 Ma from direct Rb–Sr and Re–Os isochron obtained in this study provide independent proof of the dating, respectively, of ore-stage Zn–Cu–Ge sulfides, geological significance of direct Rb–Sr dating of sphalerite. including sphalerite for the giant carbonate-hosted Kipushi base metal (+Ge) deposit in the Neoproterozoic Lufilian Keywords Kipushi . Base metals . Copperbelt . Congo . Arc, DR Congo. This is the first example of a world-class Rb–Sr isotopes . Re–Os isotopes . Pb isotopes sulfide deposit being directly dated by two independent isotopic methods. The 451 Ma age for Kipushi suggests that the ore-forming solutions did not evolve from metamorphogenic fluids mobilized syntectonically during Introduction the Pan-African-Lufilian orogeny but rather were generated in a Late Ordovician postorogenic, extensional setting. The Precise constraints on the timing of mineralization are of homogeneous Pb isotopic composition of the sulfides fundamental importance in understanding the genesis of indicates that both Cu–Ge- and Zn-rich orebodies of the hydrothermal ore deposits. -

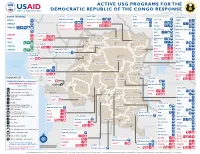

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Democratic Republic of Congo Democratic Republic of Congo Gis Unit, Monuc Africa

Map No.SP. 103 ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO GIS UNIT, MONUC AFRICA 12°30'0"E 15°0'0"E 17°30'0"E 20°0'0"E 22°30'0"E 25°0'0"E 27°30'0"E 30°0'0"E Central African Republic N N " " 0 0 ' Sudan ' 0 0 ° ° 5 5 Z o n g oBangui Mobayi Bosobolo Gbadolite Yakoma Ango Yaounde Bondo Nord Ubangi Niangara Faradje Cameroon Libenge Bas Uele Dungu Bambesa Businga G e m e n a Haut Uele Poko Rungu Watsa Sud Ubangi Aru Aketi B u tt a II s ii rr o r e Kungu Budjala v N i N " R " 0 0 ' i ' g 0 n 0 3 a 3 ° b Mahagi ° 2 U L ii s a ll a Bumba Wamba 2 Orientale Mongala Co Djugu ng o R i Makanza v Banalia B u n ii a Lake Albert Bongandanga er Irumu Bomongo MambasaIturi B a s a n k u s u Basoko Yahuma Bafwasende Equateur Isangi Djolu Yangambi K i s a n g a n i Bolomba Befale Tshopa K i s a n g a n i Beni Uganda M b a n d a k a N N " Equateur " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Lubero ° 0 Ingende B o e n d e 0 Gabon Ubundu Lake Edward Opala Bikoro Bokungu Lubutu North Kivu Congo Tshuapa Lukolela Ikela Rutshuru Kiri Punia Walikale Masisi Monkoto G o m a Yumbi II n o n g o Kigali Bolobo Lake Kivu Rwanda Lomela Kalehe S S " KabareB u k a v u " 0 0 ' ' 0 Kailo Walungu 0 3 3 ° Shabunda ° 2 2 Mai Ndombe K ii n d u Mushie Mwenga Kwamouth Maniema Pangi B a n d u n d u Bujumbura Oshwe Katako-Kombe South Kivu Uvira Dekese Kole Sankuru Burundi Kas ai R Bagata iver Kibombo Brazzaville Ilebo Fizi Kinshasa Kasongo KasanguluKinshasa Bandundu Bulungu Kasai Oriental Kabambare K e n g e Mweka Lubefu S Luozi L u s a m b o S " Tshela Madimba Kwilu Kasai -

Kipushi Project Democratic Republic of Congo NI 43-101 Technical Report (Revision 2) September 2012

Kipushi Project Democratic Republic of Congo NI 43-101 Technical Report (Revision 2) September 2012 Prepared for Ivanplats Limited Document Ref.: 984C-R-13 Qualified persons: Victor Kelly, BA, FAusIMM, P Eng. - Geologist Julian Bennett, BSc, FIMMM, C Eng. - Mining engineer David JF Smith CEng – IMC Director of Mining Kipushi Zinc Mine Project Democratic Republic of Congo NI 43-101 Technical Report (Revision 2) FINAL REPORT Page i Table of Contents 1 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 1 2 INTRODUCTION AND TERMS OF REFERENCE ............................................................... 5 3 RELIANCE ON OTHER EXPERTS ................................................................................... 6 4 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION ................................................................... 6 4.1 Legal Title ............................................................................................................................ 7 4.1.1 Mineral Property and Title in the DRC ................................................................................ 7 4.1.2 Surface Rights Title ............................................................................................................ 10 4.1.3 Royalties ............................................................................................................................ 10 4.1.4 Environmental Obligations............................................................................................... -

The Full Article

International Journal Of Advanced Research in Engineering& Management (IJAREM) ISSN: 2456-2033 || PP. 12-19 Economic analysis of potato sale in zero and one fork restaurants of Lubumbashi in DR Congo Kirongozi Swedi1, Byamungu Barasima Frederic1, Abedi Ramazani3, Mabenda Kapepe Fabien,2 Nkulu Masengo Lucien1, Kilela Mwanasomwe Jacques4, Mulonza Katalay1, and Nkulu Mwine Fyama Jules1 1. Research Unity in economy and development, Agronomy faculty, Lubumbashi University, PO box 1825, Haut Katanga, DR Congo 2. Physical Education and sport management, High pedagogical Institute of Lubumbashi, PO box 1796, Haut Katanga, DR Congo 3. Research Unity in plant production, Agronomy faculty, Lubumbashi University, PO box 1825, Haut Katanga, DR Congo 4. Research Unity in Landscape ecology and ecological restoration, Lubumbashi University, PO box 1825, Haut Katanga, DR Congo. Abstract: The present study was aiming to asses economically the potato sale in two different categories of Lubumbashi restaurants (category: 0 to 1 fork restaurants). Specifically, daily consumption was to be quantified, to determine the unit price comparing the margin profit and the financial profitability achieved by shareholders. For achieving this goal, a survey was conducted to seventy restaurant owners located in Lubumbashi, Kamalondo and Kenya township. The restaurant lists established according to the provincial tourism ministry categorization was used to find the concerned restaurant. Data on the sociodemographic features, the input and output costs, the unit price, the origin of potatoes, etc. were collected using a survey questionnaire. The result showed that the daily consumption of potatoes in these restaurants was nearly the same, although the restaurant category could be different. On the contrary, in spite of the profitability of the potato sale in these two types of restaurants, the owners of one fork restaurants are chalking up the high profit margin in comparison of those of zero fork restaurants, and then the potato sale in one fork restaurants is indicated to be more profitable. -

Musebe Artisanal Mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo

Gold baseline study one: Musebe artisanal mine, Katanga Democratic Republic of Congo Gregory Mthembu-Salter, Phuzumoya Consulting About the OECD The OECD is a forum in which governments compare and exchange policy experiences, identify good practices in light of emerging challenges, and promote decisions and recommendations to produce better policies for better lives. The OECD’s mission is to promote policies that improve economic and social well-being of people around the world. About the OECD Due Diligence Guidance The OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Due Diligence Guidance) provides detailed recommendations to help companies respect human rights and avoid contributing to conflict through their mineral purchasing decisions and practices. The OECD Due Diligence Guidance is for use by any company potentially sourcing minerals or metals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas. It is one of the only international frameworks available to help companies meet their due diligence reporting requirements. About this study This gold baseline study is the first of five studies intended to identify and assess potential traceable “conflict-free” supply chains of artisanally-mined Congolese gold and to identify the challenges to implementation of supply chain due diligence. The study was carried out in Musebe, Haut Katanga, Democratic Republic of Congo. This study served as background material for the 7th ICGLR-OECD-UN GoE Forum on Responsible Mineral Supply Chains in Paris on 26-28 May 2014. It was prepared by Gregory Mthembu-Salter of Phuzumoya Consulting, working as a consultant for the OECD Secretariat. -

Mecanisme De Referencement

EN CAS DE VIOLENCE SEXUELLE, VOUS POUVEZ VOUS ORIENTEZ AUX SERVICES CONFIDENTIELLES SUIVANTES : RACONTER A QUELQU’UN CE QUI EST ARRIVE ET DEMANDER DE L’AIDE La/e survivant(e) raconte ce qui lui est arrivé à sa famille, à un ami ou à un membre de la communauté; cette personne accompagne la/e survivant(e) au La/e survivant(e) rapporte elle-même ce qui lui est arrivé à un prestataire de services « point d’entrée » psychosocial ou de santé OPTION 1 : Appeler la ligne d’urgence 122 OPTION 2 : Orientez-vous vers les acteurs suivants REPONSE IMMEDIATE Le prestataire de services doit fournir un environnement sûr et bienveillant à la/e survivant(e) et respecter ses souhaits ainsi que le principe de confidentialité ; demander quels sont ses besoins immédiats ; lui prodiguer des informations claires et honnêtes sur les services disponibles. Si la/e survivant(e) est d'accord et le demande, se procurer son consentement éclairé et procéder aux référencements ; l’accompagner pour l’aider à avoir accès aux services. Point d’entrée médicale/de santé Hôpitaux/Structures permanentes : Province du Haut Katanga ZS Lubumbashi Point d’entrée pour le soutien psychosocial CS KIMBEIMBE, Camps militaire de KIMBEIMBE, route Likasi, Tel : 0810405630 Ville de Lubumbashi ZS KAMPEMBA Division provinciale du Genre, avenue des chutes en face de la Division de Transport, HGR Abricotiers, avenue des Abricotiers coin avenue des plaines, Q/ Bel Air, Bureau 5, Centre ville de Lubumbashi. Tel : 081 7369487, +243811697227 Tel : 0842062911 AFEMDECO, avenue des pommiers, Q/Bel Air, C/KAMPEMBA, Tel : 081 0405630 ZS RUASHI EASD : n°55, Rue 2, C/ KATUBA, Ville de Lubumbashi.