The God Is Blue. New and Original Poems with a Manifesto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Babel by Patti Smith

Read and Download Ebook Babel... Babel Patti Smith PDF File: Babel... 1 Read and Download Ebook Babel... Babel Patti Smith Babel Patti Smith Babel Details Date : ISBN : 9780425042304 Author : Patti Smith Format : Genre : Poetry, Music, Fiction, Punk Download Babel ...pdf Read Online Babel ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Babel Patti Smith PDF File: Babel... 2 Read and Download Ebook Babel... From Reader Review Babel for online ebook Bradley says Published only as a first edition in 1978, "Babel" is a collection of poetry, prose, and stream of consciousness writing. With inspiration drawn from Rimbaud and the Beats, Smith paints a unique portrait of late 70s New York City. Rock music, sex, and Smith's life are graphically and beautifully illustrated. Smith's first album "Horses" was just three years earlier. Some of the writing in this book later appeared as spoken word monologues on her albums including "Babelogue" which appears on her 1978 release "Easter." Smith is undeniably the Godmother of Punk. While this book truly encapsulates the essence of her life and struggles in New York during the 70s, it isn't a very polished collection. With lowercase text, misspelled words, and improper punctuation, the writing can be challenging at times. However, perhaps that's the point. What could be more punk in the literary world than defying all literature's conventions? Jamie Ruiz says Wicked! Jennifer says Patti Smith is a true American artist and though her poetry tends to be more like an American Rimbaud, crude, poignant, and funny, she is not for everyone. The godmother of punk she is now in her 60's and still remains articulate and true to her artform. -

Alexander Literary Firsts & Poetry Rare Books

ALEXANDER LITERARY FIRSTS & POETRY RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE TWENTY- SEVEN 2 Alexander Rare Books [email protected]/ (802) 476‐0838 ALEXANDER RARE BOOKS – LITERARY FIRSTS & POETRY Mark Alexander 234 Camp Street Barre, VT 05641 (802) 476-0838 [email protected] Catalogue Twenty–Seven: All items are US, CN or UK Hardcover First Editions & First Printings unless otherwise stated. All items guaranteed & are refundable for any reason within 30 days. Subject to prior sale. VT residents please add 6% sales tax. Checks, Money Orders, Paypal & most credit cards accepted. Net 30 days. Libraries & institutions billed according to need. Reciprocal terms offered to the trade. SHIPPING IS FREE IN THE US (generally Priority Mail) & CANADA, elsewhere $13 per shipment. Visit AlexanderRareBooks.com for cover scans and photos of most catalogued items. I encourage you to visit my website for the latest acquisitions. The best items usually appear on my website, then appear in my catalogues, before appearing elsewhere online. I am always interested in acquiring first editions, single copies or collections, and particularly modernist & contemporary poetry. Thank you in advance for perusing this catalogue. CATALOGUE TWENTY-SEVEN 1) Adam, Helen. THE BELLS OF DIS. West Branch, Iowa: Coffee House Press, 1985. Tall sewn illustrated wraps. Morning Coffee Chapbook: 12. One of 500 copies, numbered and signed by the poet and the artist Ann Mikolowski. A lovely book hand set and hand sewn. Bottom tips bumped, else fine. (10690) $20.00 2) Armantraut, Rae. CONCENTRATE. Green River, VT: Longhouse, 2007. Small (3 x 4 1/2 in.) accordion style chapbook attached to unprinted card covers, with wrap around band. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

Galway Kinnell - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Galway Kinnell - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Galway Kinnell(1 February 1927) Galway Kinnell is an American poet. He was Poet Laureate of Vermont from 1989 to 1993. An admitted follower of <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/walt- whitman/">Walt Whitman</a> , Kinnell rejects the idea of seeking fulfillment by escaping into the imaginary world. His best-loved and most anthologized poems are "St. Francis and the Sow" and "After Making Love We Hear Footsteps". <b>Biography</b> Born in Providence, Rhode Island, Kinnell said that as a youth he was turned on to poetry by <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/edgar-allan-poe/">Edgar Allan Poe</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/emily- dickinson/">Emily Dickinson</a>, drawn to both the musical appeal of their poetry and the idea that they led solitary lives. The allure of the language spoke to what he describes as the homogeneous feel of his hometown, Pawtucket, Rhode Island. He has also described himself as an introvert during his childhood. Kinnell studied at Princeton University, graduating in 1948 alongside friend and fellow poet <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/william-stanley- merwin/">W.S. Merwin</a>. He received his master of arts degree from the University of Rochester. He traveled extensively in Europe and the Middle East, and went to Paris on a Fulbright Fellowship. During the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States caught his attention. Upon returning to the US, he joined CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) and worked on voter registration and workplace integration in Hammond, Louisiana. -

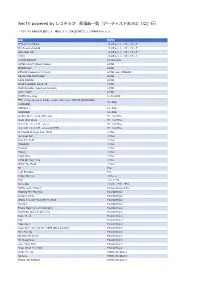

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I Feel Like I Am Always Running from Someone

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I feel like I am always running from someone. I can feel their eyes watching me. My name is Bella Swan; I am 16 years old and a sophomore in high school. My father is Charlie Swan is Mafia lord and his best friend Carlisle Cullen is his partner in crime who I have heard a lot about over the years. My mother is Renee Swan she is definitely one the sweetest mother's in the world but she can be your worst nightmare if you get on her bad side. I have four older siblings Sam, Jacob, Rose, and Alice. I am the baby of the family which also means I get the most unwanted attention and my siblings have a hard time accepting that I'm not a little girl anymore, I am almost an adult. My ex-boyfriend Chris was murdered when I was 15 years old. He was definitely the sweetest boyfriend you could have, I loved him and wanted to marry him in the future, but that will never happen with him. Many people want me for my families' money, but he wanted me for who I was. The mafia life is what I grew up with living in New York; I learned you can't trust anyone outside of the family except for the Cullen's. I also didn't trust people because of what I had dealt with the past sixteen years. Which brings me here in Chicago at Mr. Cullen's house, my father announced to me last week that I was arranged to be married to Mr. -

Modern Poetry Seminar “Shifting Poetics: from High Modernism to Eco-Poetics to Black Lives Matter”

San José State University Department of English and Comparative Literature ENGLISH 211: Modern Poetry Seminar “Shifting Poetics: From High Modernism to Eco-Poetics to Black Lives Matter” Spring 2021 Instructor: Prof. Alan Soldofsky Office Location: FO 106 Telephone: 408-924-4432 Email: [email protected] Virtual Office Hours: M, W 3:00 – 4:30 PM, and Th p.m. by appointment Class Days/Time: Synchronous Zoom Meetings M 7:00 – 8:30 PM; Asynchronous on Canvas (24/7) Classroom: Zoom Credit Units: 4 Credits Course Description This seminar is designed to engage students in an immersive study of salient themes and innovations in selected poets from the 20th and 21st centuries. The curriculum will include practice in close reading/explication of selected poems. The course will be taught in a partially synchronous distance learning mode, using SJSU’s Canvas and Zoom platforms, with weekly Monday Zoom class meetings, 7:00 – 8:15 p.m. The course may be taken two times for credit (toward an MA or MFA degree). Thematic Focus Shifting Cultural Politics and Poetics from High Modernism to Eco-Poetics to Black Lives Matter (1909 – 2021) The emphasis during the semester will be on the evolving poetics and associated cultural politics as viewed through various aesthetic movements in poetry from the high modernist period to the present. During the semester the curriculum will include reading one or more poems (online) by the following poets: W.B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Marianne Moore, Robinson Jeffers, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, H. -

Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014 Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rutter, E. (2014). Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1136 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Copyright by Emily Ruth Rutter 2014 ii CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter Approved March 12, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda A. Kinnahan Kathy L. Glass Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Laura Engel Thomas P. Kinnahan Associate Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Greg Barnhisel Dean, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Chair, English Department Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of English iii ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda A. -

(Self-) Portraits in the Work of John Berryman, John Ashbery, Anne Carson, and Nan Goldin

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 “Whispers Out of Time”: Memorializing (Self-) Portraits in the Work of John Berryman, John Ashbery, Anne Carson, and Nan Goldin Andrew D. King The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3185 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “WHISPERS OUT OF TIME”: MEMORIALIZING (SELF-) PORTRAITS IN THE WORK OF JOHN BERRYMAN, JOHN ASHBERY, ANNE CARSON, AND NAN GOLDIN By ANDREW D. KING A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 ANDREW D. KING All rights reserved ii “WHISPERS OUT OF TIME”: MEMORIALIZING (SELF-) PORTRAITS IN THE WORK OF JOHN BERRYMAN, JOHN ASHBERY, ANNE CARSON, AND NAN GOLDIN By Andrew D. King This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date George Fragopoulos Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT “Whispers Out of Time”: Memorializing (Self-)Portraits in the work of John Berryman, John Ashbery, Anne Carson, and Nan Goldin by Andrew D. King Advisor: George Fragopoulos This thesis documents four distinct post-WWII North American writers and artists—the poet John Berryman, the poet John Ashbery, the classicist and writer Anne Carson, and the photographer Nan Goldin—who expanded traditional definitions and practices of portraiture. -

Galway Kinnell: Adamic Poet and Deep Imagist. Leo Luke Marcello Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 Galway Kinnell: Adamic Poet and Deep Imagist. Leo Luke Marcello Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Marcello, Leo Luke, "Galway Kinnell: Adamic Poet and Deep Imagist." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2930. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2930 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

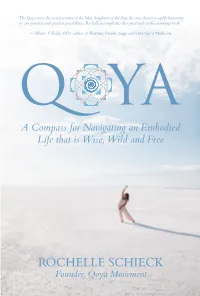

ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’S QOYA: a Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life That Is Wise, Wild and Free

“The Qoya were the sacred women of the Inka, daughters of the Sun, the ones chosen to uplift humanity to our grandest and greatest possibilities. Rochelle accomplishes this great task in this stunning book.” —Alberto Villoldo, PhD, author of Shaman, Healer, Sage and One Spirit Medicine Q YA A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free ROCHELLE SCHIECK Founder, Qoya Movement Praise for Rochelle Schieck’s QOYA: A Compass for Navigating an Embodied Life that is Wise, Wild and Free “Through the sincere, witty, and profound sharing of her own life experiences, Rochelle reveals to us a valuable map to recover one’s joy, confidence, and authenticity. She shows us the way back to love by feeling gratitude for one’s own experiences. She offers us price- less tools and practices to reconnect with our innate intelligence and sense of knowing what is right for us. More than a book, this is a companion through difficult moments or for getting from well to wonderful!” —Marcela Lobos, shamanic healer, senior staff member at the Four Winds Society, and co-founder of Los Cuatro Caminos in Chile “Qoya represents the future – the future of spirituality, femininity, and movement. If I’ve learned anything in my work, it is that there is an awakening of women everywhere. The world is yearning for the balance of the feminine essence. This book shows us how to take the next step.” —Kassidy Brown, co-founder of We Are the XX “Rochelle Schieck has made her life into a solitary vow: to remem- ber who she is – not in thought or theory – but in her bones, in the truth that only exists in her body.