The Generic Style Rules for Linguistics: Abridged Langsci Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Format Interlinearized Linguistic Examples Three-Line Format

abbreviations in small caps How to format interlinearized linguistic examples Three-line format (1) ➜a.➜ʔu–gʷəč’–əd ➜čəxʷ ➜ti ➜sqʷəbayʔ use tabs to separate words and line them up with the interlinear gloss ➜PFV–look.for–ICS ➜2SG ➜SPEC ➜dog ➜‘you looked for the dog’ use a period instead of a space to join separate words in a single gloss ➜b.➜ *ʔu–gʷəč ➜čəxʷ ➜ti ➜sqʷəbayʔ ➜PFV–look.for ➜2SG ➜SPEC ➜dog divide morphemes with an n-dash or a plus; make sure they match one-to-one with the ➜*‘you looked for the dog’ interlinear gloss align glosses with words, not with punctuation (Hess 1993: 16) equal signs are often used to mark clitic- (2) hay la%–du–b=#x" !# ti!i& c’i%c’i% boundaries and other special divisions (but then look.for–LC–MD=now PR DIST fish.hawk use it consistently for only one of these) indent the second line of long examples ti!i& tu=s=cut–t–#b=s !# ti!i& s$#tx"#d and leave space before it; use the same tab DIST PST=NP=speak–ICS–MD=3PO PR DIST bear spacing as for subordinate numbering ‘then fish-hawk remembers what bear said to him’ (lit. ‘then his was-spoken-by-bear is remembered by fish-hawk’) indicate a change of cited language and/or give the (Hess 1993: 194, line 46) language name if you are using more than one if data is not from your own Bella Coola fieldwork, cite your sources (with page numbers for (3) !a&nap–is=k"=c’ ta=qiiqtii=t% wa=s=k"acta–tu–m published material) know–3SG:3SG=QTV=now D=baby=D D=NP=name–CS–3SG.PASS use a colon to separate values of inflectional use single quotes for all free categories that are cumulatively expressed x=ti=man=& translations (and for glosses in the by the same affix PR=D=father=1PL.PO text of the paper) ‘the baby knew what he had been named by our father’ number examples sequentially (Davis & Saunders 1980: 108, line 12) throughout the paper Word-processing tip: use the “Keep lines together” option to prevent page breaks from interrupting interlinearized examples and separating lines across pages. -

Automatic Interlinear Glossing for Under-Resourced Languages Leveraging Translations

Automatic Interlinear Glossing for Under-Resourced Languages Leveraging Translations Xingyuan Zhaoy, Satoru Ozakiy, Antonios Anastasopoulosz, Graham Neubigy, Lori Leviny yLanguage Technologies Institute, Carnegie Mellon University zDepartment of Computer Science, George Mason University {xingyuanz,sozaki}@andrew.cmu.edu [email protected] {gneubig,lsl}@cs.cmu.edu Abstract Interlinear Glossed Text (IGT) is a widely used format for encoding linguistic information in language documentation projects and scholarly papers. Manual production of IGT takes time and requires linguistic expertise. We attempt to address this issue by creating automatic gloss- ing models, using modern multi-source neural models that additionally leverage easy-to-collect translations. We further explore cross-lingual transfer and a simple output length control mech- anism, further refining our models. Evaluated on three challenging low-resource scenarios, our approach significantly outperforms a recent, state-of-the-art baseline, particularly improving on overall accuracy as well as lemma and tag recall. 1 Introduction The under-documentation of endangered languages is an imminent problem for the linguistic commu- nity. Of the 7,000 languages in the world, an estimated 50% will face extinction in the coming decades, while around 35–42% still remain substantially undocumented (Austin and Sallabank, 2011; Seifart et al., 2018). Perhaps these numbers are no surprise when one acknowledges the difficulty of language documentation – fieldwork demands time, cultural understanding, linguistic expertise, and financial sup- port among a myriad of other factors. Consequently, an important task for the linguistic community is to facilitate the otherwise daunting documentation process as much as possible. Documentation is not a cure-all for language loss, but it is an important part of language preservation; even in an unfortunate worst-case scenario where a language does disappear, a permanent record of the language is saved for posterity, and could hopefully be useful for revitalization purposes. -

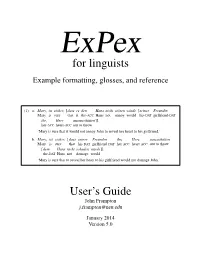

For Linguists User's Guide

ExPex for linguists Example formatting, glosses, and reference (1) a. Maryi ist sicher, [dass es den Hans nicht storen¨ wurde¨ [seiner Freundin Mary is sure that it the-ACC Hans not annoy would his-DAT girlfriend-DAT ihri Herz auszuschutten¨ ]]. her-ACC heart-ACC out to throw ‘Mary is sure that it would not annoy John to reveal her heart to his girlfriend.’ b. Maryi ist sicher, [dass seiner Freunden ihri Herz auszuchutten¨ Mary is sure that his-DAT girlfriend-DAT her-ACC heart-ACC out to throw [dem Hans nicht schaden wurde¨ ]]. the-DAT Hans not damage would ‘Mary is sure that to reveal her heart to his girlfriend would not damage John.’ User’s Guide John Frampton [email protected] January 2014 Version 5.0 Contents 1 Introduction ............................... 1 1.1 Changes ............................. 1 1.2 LaTex/Texcooperation . 2 1.3 Acknowledgements . 3 2 Somepreliminaryexamples . 4 3 XKVparameterization . 8 4 Exampleswithoutparts . 10 4.1 Explicit example numbers; Formatting the example number ..... 13 5 Exampleswithlabeledparts:Basics . 15 5.1 nopreamble ......................... 17 5.2 Stipulatedlabels . 18 6 More on examples, with and without labeled parts . 18 6.1 Anchoring ........................... 18 6.2 Formatting the labels . 19 6.3 Aligning the labels . 21 6.4 Relative versus fixed dimensions . 23 6.5 Userdesignedlabeling . 23 6.6 The parameter sampleexno ................... 25 6.7 IJAL style format of multiline examples . 26 6.8 Footnotes and endnotes . 28 7 Userdefinedstyles ........................... 30 8 Judgmentmarks ............................ 32 9 Glosses ................................ 34 9.1 Parameters .......................... 36 9.2 Exceptional \gla items ..................... 39 10 Nlevel glosses; an alternate coding syntax . -

Using Interlinear Glosses As Pivot in Low-Resource Multilingual Machine Translation

Using Interlinear Glosses as Pivot in Low-Resource Multilingual Machine Translation Zhong Zhou Lori Levin David R. Mortensen Alex Waibel Carnegie Mellon University Carnegie Mellon University Carnegie Mellon University Carnegie Mellon University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Karlsruhe Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract We demonstrate a new approach to Neu- ral Machine Translation (NMT) for low- resource languages using a ubiquitous lin- guistic resource, Interlinear Glossed Text (IGT). IGT represents a non-English sen- Figure 1: Multilingual NMT. tence as a sequence of English lemmas and morpheme labels. As such, it can serve as a pivot or interlingua for NMT. Our contribution is four-fold. Firstly, we pool IGT for 1,497 languages in ODIN (54,545 glosses) and 70,918 glosses in Ara- paho and train a gloss-to-target NMT sys- Figure 2: Using interlinear glosses as pivot to translate in tem from IGT to English, with a BLEU multilingual NMT in Hmong, Chinese, and German. score of 25.94. We introduce a multi- lingual NMT model that tags all glossed resource settings (Firat et al.(2016)Firat, Cho, text with gloss-source language tags and and Bengio; Zoph and Knight(2016); Dong train a universal system with shared atten- et al.(2015)Dong, Wu, He, Yu, and Wang; Gillick tion across 1,497 languages. Secondly, we et al.(2016)Gillick, Brunk, Vinyals, and Subra- use the IGT gloss-to-target translation as manya; Al-Rfou et al.(2013)Al-Rfou, Perozzi, a key step in an English-Turkish MT sys- and Skiena; Zhou et al.(2018)Zhou, Sperber, and tem trained on only 865 lines from ODIN. -

The Faith Between the Lines: a Survey of Doctrinal Language in the Old Northumbrian Glosses to the Gospel of Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels

The Faith Between the Lines: A Survey of Doctrinal Language in the Old Northumbrian Glosses to the Gospel of Matthew in the Lindisfarne Gospels Research MA Thesis Medieval Studies Student Name: Jelle Merlijn Zuring Student Number: 3691608 Date: 27-6-2017 First Reader: Dr. Marcelle Cole Second Reader: Dr. Aaron Griffith Utrecht University, Department of History 1 2 Table of Contents: Chapter 1: Introduction and Literature Review p. 5 Chapter 2: St Cuthbert and his Community p. 10 Chapter 3: The Manuscript and its Glossator p. 15 Chapter 4: The English Benedictine Reform p. 18 Chapter 5: St Cuthbert’s Community and its Relations with the South p. 24 Chapter 6: A Survey of Doctrinal Language in the Gospel of Matthew p. 29 Chapter 7: Conclusion p. 47 Bibliography p. 50 Appendix A p. 55 Appendix B p. 66 3 Abbreviations ASC Benjamin Thorpe, ed. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, According to the Several Original Authorities. London (1861) 2 vols. B&T J. Bosworth and T.N. Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. Oxford (1882-1893); T.N. Toller, An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary: Supplement. Oxford (1908-1921) CHM J.R. Clark Hall, A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, 4th ed. with suppl. by H.D. Meritt. Cambridge (1960) DOEC Dictionary of Old English Web Corpus. (2007) Antonette diPaolo Healey et al. eds. Toronto (http://www.doe.utoronto.ca/) HE Venerabilis Bedae Historia Ecclesiastice Gentis Anglorum HR Symeon of Durham’s Historia Regum HSC Ted Johnson South, ed. Historia de Sancto Cuthberto: A History of Saint Cuthbert and a Record of his Patrimony. Suffolk (2002). -

E-Research for Linguists

e-Research for Linguists Dorothee Beermann Pavel Mihaylov Norwegian University of Science Ontotext, and Technology Sofia, Bulgaria Trondheim, Norway [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Modern approaches to Language Description and Documentation are not possible without the tech- e-Research explores the possibilities offered nology that allows the creation, retrieval and stor- by ICT for science and technology. Its goal is age of diverse data types. A field whose main aim to allow a better access to computing power, data and library resources. In essence e- is to provide a comprehensive record of language Research is all about cyberstructure and being constructions and rules (Himmelmann, 1998) is cru- connected in ways that might change how we cially dependent on software that supports the effort. perceive scientific creation. The present work Talking to the language documentation community advocates open access to scientific data for lin- Bird (2009) lists as some of the immediate tasks that guists and language experts working within linguists need help with; interlinearization of text, the Humanities. By describing the modules of validation issues and, what he calls, the handling an online application, we would like to out- of uncertain data. In fact, computers always have line how a linguistic tool can help the lin- guist. Work with data, from its creation to played an important role in linguistic research. Start- its integration into a publication is not rarely ing out as machines that were able to increase the perceived as a chore. Given the right tools efficiency of text and data management, they have however, it can become a meaningful part of become tools that allow linguists to pursue research the linguistic investigation. -

A Catalogue of Manuscripts Known to Contain Old English Dry-Point Glosses

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 A catalogue of manuscripts known to contain Old English dry-point glosses Studer-Joho, Dieter Abstract: While quill and ink were the writing implements of choice in the Anglo-Saxon scriptorium, other colouring and non-colouring writing implements were in active use, too. The stylus, among them, was used on an everyday basis both for taking notes in wax tablets and for several vital steps in the creation of manuscripts. Occasionally, the stylus or perhaps even small knives were used for writing short notes that were scratched in the parchment surface without ink. One particular type of such notes encountered in manuscripts are dry-point glosses, i.e. short explanatory remarks that provide a translation or a clue for a lexical or syntactic difficulty of the Latin text. The present study provides a comprehensive overview of the known corpus of dry-point glosses in Old English by cataloguing the 34 manuscripts that are currently known to contain such glosses. A first general descriptive analysis of the corpus of Old English dry-point glosses is provided and their difficult visual appearance is discussed with respect to the theoretical and practical implications for their future study. Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-143088 Monograph Published Version Originally published at: Studer-Joho, Dieter (2017). A catalogue of manuscripts known to contain Old English dry-point glosses. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto. -

Colorado Technical University Enabling A

COLORADO TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ENABLING A LEGACY MORPHOLOGICAL PARSER TO USE DATR-BASED LEXICONS VOLUME 1 of 2 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE BY MICHAEL A. COLBURN M.C.I.S., University of Denver, Denver, CO, 1991 M.A., University of Texas, Arlington, TX, 1981 B.A., Rockmont College, Denver, CO, 1975 DENVER, COLORADO DECEMBER 1999 ENABLING A LEGACY MORPHOLOGICAL PARSER TO USE DATR-BASED LEXICONS BY MICHAEL A. COLBURN THE DISSERTATION IS APPROVED __________________________________________ Dr. Carol Keene, Committee Chair __________________________________________ Dr. H. Andrew Black __________________________________________ Dr. Jay Rothman __________________________________________ Date Approved ii ABSTRACT This research is an investigation of the feasibility and desirability of using DATR with AMPLE, a legacy morphology exploration tool developed by the Summer Institute of Linguistics. The research demonstrates the feasibility of using DATR with AMPLE by showing how DATR can be used to encode the lexical information required by AMPLE and by presenting an interface between AMPLE and DATR-based lexicons that does not require modification of AMPLE itself. The desirability of using DATR with AMPLE is shown by demonstrating that there are generalizations that cannot be captured using AMPLE’s lexical knowledge representation language (LKRL) that can be captured in DATR, thereby reducing redundancy of lexical information. The research demonstrated the truth of the four hypotheses. In order to prove these hypotheses, the author analyzed the morphophonology and morphotactics of a Papuan language, Ogea, and built a comprehensive AMPLE unified database lexicon that supports the parsing of every example found in the author's write-up of Ogea. -

Modelling and Annotating Interlinear Glossed Text from 280 Di Erent

Modelling and annotating interlinear glossed text from 280 dierent endangered languages as Linked Data with LIGT Sebastian Nordho Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft (ZAS) [email protected] Abstract This paper reports on the harvesting, analysis, and annotation of 20k documents from 4 dif- ferent endangered language archives in 280 dierent low-resource languages. The documents are heterogeneous as to their provenance (holding archive, language, geographical area, creator) and internal structure (annotation types, metalanguages), but they have the ELAN-XML format in common. Typical annotations include sentence-level translations, morpheme-segmentation, morpheme-level translations, and parts-of-speech. The ELAN format gives a lot of freedom to document creators, and hence the data set is very heterogeneous. We use regularities in the ELAN format to arrive at a common internal representation of sentences, words, and mor- phemes, with translations into one or more additional languages. Building upon the paradigm of Linguistic Linked Open Data (LLOD, Chiarcos et al. (2012b)), the document elements receive unique identiers and are linked to other resources such as Glottolog for languages, Wikidata for semantic concepts, and the Leipzig Glossing Rules list for category abbreviations. We pro- vide an RDF export in the LIGT format (Chiarcos and Ionov (2019)), enabling uniform and inter- operable access with some semantic enrichments to a formerly disparate resource type dicult to access. Two use cases (semantic search and colexication) are presented to show the viability of the approach. 1 Introduction 1.1 Understudied languages A couple of major languages, most predominantly English, have been the mainstay of research and development in computational linguistics. -

Towards a General Model of Interlinear Text

Towards a General Model of Interlinear Text Cathy Bow, Baden Hughes and Steven Bird Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering University of Melbourne, Victoria 3010, Australia {cbow, badenh, sb}@cs.mu.oz.au Abstract The use of interlinear text has long been a valuable tool in linguistic description, and the development of a number of different software tools has facilitated the creation and processing of such texts. In this paper we survey of a range of interlinear texts, focusing on issues such as grouping and alignment. Abstracting away from the presentation, we look specifically at the structure of the data, in an attempt to create a general purpose data model for interlinear text. Our findings are that a four level model œ incorporating Text, Phrase, Word and Morpheme levels œ is sufficient to represent a very wide range of practice. We present an XML format for representing data in this model, and describe stylesheets for converting such data into presentational formats. Because of its generality, and the way it abstracts away from presentation, we believe the model is a suitable basis for developing archival storage formats for interlinear text and delivering interlinear text to end-users and external software tools in a web environment. 1 Introduction Interlinear texts serve a variety of purposes in linguistic research. In many cases they are used demonstrate various linguistic principles in a certain language, such as a traditional narrative included in a descriptive grammar. In textbooks or other reference material, a single line of text may be given an interlinear treatment to highlight a specific issue under discussion. -

Pdf Field Stands on a Separate Tier

ComputEL-2 Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on the Use of Computational Methods in the Study of Endangered Languages March 6–7, 2017 Honolulu, Hawai‘i, USA Graphics Standards Support: THE SIGNATURE What is the signature? The signature is a graphic element comprised of two parts—a name- plate (typographic rendition) of the university/campus name and an underscore, accompanied by the UH seal. The UH M ¯anoa signature is shown here as an example. Sys- tem and campus signatures follow. Both vertical and horizontal formats of the signature are provided. The signature may also be used without the seal on communications where the seal cannot be clearly repro- duced, space is limited or there is another compelling reason to omit the seal. How is color incorporated? When using the University of Hawai‘i signature system, only the underscore and seal in its entirety should be used in the specifed two-color scheme. When using the signature alone, only the under- score should appear in its specifed color. Are there restrictions in using the signature? Yes. Do not • alter the signature artwork, colors or font. c 2017 The Association for Computational Linguistics • alter the placement or propor- tion of the seal respective to the nameplate. • stretch, distort or rotate the signature. • box or frame the signature or use over a complexOrder background. copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 5 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ii Preface These proceedings contain the papers presented at the 2nd Workshop on the Use of Computational Methods in the Study of Endangered languages held in Honolulu, March 6–7, 2017. -

Talking in Halq'eméylem

Talking in Halq’eméylem Documenting Conversation in an Indigenous Language 2nd Edition Talking in Halq’eméylem Documenting Conversation in an Indigenous Language 2nd Edition by Siyamiyateliyot Elizabeth Phillips, Xwiyalemot Tillie Gutierrez, and Susan Russell with Sa:yisatlha Vivian Wiliams and Strang Burton University of British Columbia Occasional Papers in Linguistics 2021 ©2017 Susan Russell, Siyamiyateliyot Elizabeth Phillips, and the University of British Columbia Occasional Papers in Linguistics (UBCOPL). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced except by permission UBCOPL, Susan Russell or Siyamiyateliyot Elizabeth Philips. photographs on front and back covers ©John Russell, used with permission. First edition printed August 2017. ISBN 978-0-88865-471-7 Second Edition, published January 2021. UBCOPL Vol. 9. Printed by University of British Columbia Occasional Papers in Linguistics, Vancouver, BC, Canada. Managing Editors, E.A. Guntly and Marianne Huijsmans For information and resources related to this volume (including audio files), or to purchase additional volumes, please visit UBCOPL at http://publications.linguistics.sites.olt.ubc.ca DEDICATION To the teachers and learners of all the dialects of Halkomelem Contents Contents i Prologue: Sqwelqwels the Siyamiyateliyot –by Siyamiyateliyot Elizabeth Phillips iii Retelling of the Prologue –by Sa:yistlha Vivian Wiliams v Foreword –by Marianne Ignace vii Preface to the second edition –Marianne Huijsmans and Susan Russell xi Editor’s Preface –by E.A. Guntly xiii Author’s Preface –by Susan Russell xv Why should we collect everyday conversation in indigenous languages? xv Using Conversation Analysis with indigenous languages . xvii Why do CA? . xix Summary . xxii i Acknowledgements xxiii 1 Doing Conversation Analysis –by Susan Russell 1 1.1 Introduction .