Journal of Field Ornithology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Argentina (Custom Tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour Leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-Guided by Sam Woods

Northwest Argentina (custom tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-guided by Sam Woods Trip Report by Andrés Vásquez; most photos by Sam Woods, a few by Andrés V. Elegant Crested-Tinamou at Los Cardones NP near Cachi; photo by Sam Woods Introduction: Northwest Argentina is an incredible place and a wonderful birding destination. It is one of those locations you feel like you are crossing through Wonderland when you drive along some of the most beautiful landscapes in South America adorned by dramatic rock formations and deep-blue lakes. So you want to stop every few kilometers to take pictures and when you look at those shots in your camera you know it will never capture the incredible landscape and the breathtaking feeling that you had during that moment. Then you realize it will be impossible to explain to your relatives once at home how sensational the trip was, so you breathe deeply and just enjoy the moment without caring about any other thing in life. This trip combines a large amount of quite contrasting environments and ecosystems, from the lush humid Yungas cloud forest to dry high Altiplano and Puna, stopping at various lakes and wetlands on various altitudes and ending on the drier upper Chaco forest. Tropical Birding Tours Northwest Argentina, Nov.2015 p.1 Sam recording memories near Tres Cruces, Jujuy; photo by Andrés V. All this is combined with some very special birds, several endemic to Argentina and many restricted to the high Andes of central South America. Highlights for this trip included Red-throated -

Categorización De Las Aves De La Argentina

Categorización de las Aves de la Argentina SEGÚN SU ESTADO DE CONSERVACIÓN Informe del Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable de la Nación y de Aves Argentinas Ilustración: Leonardo González Galli - Gallito de arena AUTORIDADES Presidente de la Nación Mauricio Macri Ministro de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable Sergio Bergman Jefa de Gabinete de Asesores Patricia Holzman Secretario de Política Ambiental, Cambio Climático y Desarrollo Sustentable Diego Moreno Subsecretaría de Planificación y Ordenamiento Ambiental del Territorio Dolores María Duverges Director Nacional de Biodiversidad y Recursos Hídricos Javier Garcia Espil Director de la Dirección de Fauna Silvestre y Conservación de la Biodiversidad Santiago D'Alessio 2 Indice CONTENIDO PRÓLOGO............................................................................................................................................5 INTRODUCCIÓN...................................................................................................................................7 METODOLOGÍA...................................................................................................................................9 2.1 Procedimientos generales y cambio de metodología...............................................9 2.2 Alcance geográfico para la recategorización.............................................................9 2.3 Elaboración de la matriz de especies y selección de especies para evaluar.........10 2.4. Proceso de evaluación y categorización de especies y justificación -

Northern Argentina Tour Report 2016

The enigmatic Diademed Sandpiper-Plover in a remote valley was the bird of the trip (Mark Pearman) NORTHERN ARGENTINA 21 OCTOBER – 12 NOVEMBER 2016 TOUR REPORT LEADER: MARK PEARMAN Northern Argentina 2016 was another hugely successful chapter in a long line of Birdquest tours to this region with some 524 species seen although, importantly, more speciality diamond birds were seen than on all previous tours. Highlights in the north-west included Huayco Tinamou, Puna Tinamou, Diademed Sandpiper-Plover, Black-and-chestnut Eagle, Red-faced Guan, Black-legged Seriema, Wedge-tailed Hilstar, Slender-tailed Woodstar, Black-banded Owl, Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Black-bodied Woodpecker, White-throated Antpitta, Zimmer’s Tapaculo, Scribble-tailed Canastero, Rufous-throated Dipper, Red-backed Sierra Finch, Tucuman Mountain Finch, Short-tailed Finch, Rufous-bellied Mountain Tanager and a clean sweep on all the available endemcs. The north-east produced such highly sought-after species as Black-fronted Piping- Guan, Long-trained Nightjar, Vinaceous-breasted Amazon, Spotted Bamboowren, Canebrake Groundcreeper, Black-and-white Monjita, Strange-tailed Tyrant, Ochre-breasted Pipit, Chestnut, Rufous-rumped, Marsh and Ibera Seedeaters and Yellow Cardinal. We also saw twenty-fve species of mammal, among which Greater 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Northern Argentina 2016 www.birdquest-tours.com Naked-tailed Armadillo stole the top slot. As usual, our itinerary covered a journey of 6000 km during which we familiarised ourselves with each of the highly varied ecosystems from Yungas cloud forest, monte and badland cactus deserts, high puna and altiplano, dry and humid chaco, the Iberá marsh sytem (Argentina’s secret pantanal) and fnally a week of rainforest birding in Misiones culminating at the mind-blowing Iguazú falls. -

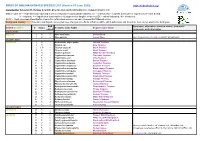

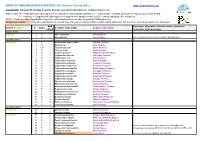

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Fernando Marques Dos Santos BIOLOGIA REPRODUTIVA DE PASSERIFORMES SUBTROPICAIS DO SUL DO BRASIL

Fernando Marques dos Santos BIOLOGIA REPRODUTIVA DE PASSERIFORMES SUBTROPICAIS DO SUL DO BRASIL: testando a teoria de convergência latitudinal das fenologias reprodutivas Dissertação apresentada ao Setor de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenção do grau de mestre em Ecologia e Conservação. Orientador: Dr. James Joseph Roper Curitiba – PR 2014 AGRADECIMENTOS À Uschi Wischhoff pelos anos de harmonia entre colaboração científica e convivência. Ao James Roper pelos valiosos conselhos e incentivo em observar a natureza. À Talita Braga, Gustavo Cerboncini e Rafaela Bobato pelo auxílio em campo de extrema competência. À Bióloga Ana Cristina Barros pelo bom humor e receptividade nas áreas de estudo. Aos guardas dos Mananciais da Serra e Casa da Cultura da Água pelo respeito à fauna, e especialmente Odirlei, Emerson e Carlos pelos ninhos encontrados. Aos professores e funcionários da PPGECO pela imensurável dedicação. À CAPES pela bolsa de mestrado. Aos meus pais, Ocimara e Mário, por tudo. Ao povo brasileiro pela oportunidade em contribuir com conhecimento de importância à longo prazo. “Every now and then I break free from the office, the computer, the telephone, the piles of manuscripts, and take up an invitation to visit a field site somewhere. I stumble over logs, get ripped by thorns, bitten by horseflies, stuck in mud, sunburned, and bruised. I sweat, groan, spit, curse, and generally have a wonderful time. I fight back tears when I see old, long- forgotten friends---the wildflowers, ferns, trees, salamanders, fungi, and beetles I once knew so well but whose names now elude me as often as not. -

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 15 July 2021) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 15 July 2021) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Trip Report Córdoba Endemics Pre-Tour Extension 21St to 24Th September 2015 (4 Days) Northern Argentina 25Th September to 15Th October 2015 (21 Days)

Trip Report Córdoba Endemics Pre-tour Extension 21st to 24th September 2015 (4 days) Northern Argentina 25th September to 15th October 2015 (21 days) Burrowing Parrot by David Shackelford Trip report compiled by tour leader: Luis Segura RBT Trip Report Northern Argentina & Córdoba Endemics 2015 2 Day 1: September 21st, 2015 – Our Northern Argentina 2015 tour started with Córdoba Endemics extension. We left the hotel with Peter and Alison Beer, who arrived the previous night from Eastern Patagonia, where they spent a few days birding the Valdés Peninsula area. On arrival to the airport, Adrian –our local Trogon Tours’ leader, took Peter and Alison for some “parking birding” at Córdoba airport, while Luis waited for Terry Rosenmeier and Karen Kluge to arrive from Buenos Aires. The short birding break produced some nice birds for Peter and Alison, who got Guira Cuckoo, Monk Parakeet, Brown Cacholote, Lark-like Brushrunner, Southern Martin, Shiny and Screaming Cowbirds and Greyish Olrog’s Cinclodes by Luis Segura Baywing among others. With Karen and Terri already on board, we drove down to the small village of Icho Cruz, which sits at the foot of the Córdoba Hills. We arrived at our lodge and checked in for the next two nights. We set off birding the surroundings, while waited for lunch to be served. Our first pleasant surprise was an active nest of Brown Cacholote on a tree right in front of our lodge’s main entrance. The gardens of our lodge were very productive, and we saw some wonderful birds including Grey-hooded Parakeet, Scimitar-billed Woodcreeper, Blue-and-Yellow Tanager and Golden-billed Saltator. -

Threatened Birds of Bolivia Final Report

Threatened Birds of Bolivia Project 2004 to 2009 Proyecto Aves Amenazadas de Bolivia 2004 a 2009 Final Report Contact Details Dr Ross MacLeod Division of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology Graham Kerr Building, Glasgow University Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK. Email: [email protected] Contents Meeting the Aim & Objectives ....................................................................................................... 4 Original Aim: ...........................................................................................................................4 Original Objectives: .................................................................................................................4 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Conservation Importance of Bolivian Ecosystems ............................................................6 1.2 Threats to Bolivian Ecosystems .........................................................................................6 1.3 Bolivia’s Threatened Birds, IBAs and Conservation.........................................................6 1.4 Conservation Leadership Programme (BP Conservation Award) Projects .......................8 2 Conservation Work Completed................................................................................................. 9 2.1 Identifying Bolivian Important Bird Areas ........................................................................9 2.2 Royal Cinclodes & -

Northern Argentina September 27Th to October 17Th, 2016 (21 Days) Trip Report

Northern Argentina September 27th to October 17th, 2016 (21 days) Trip Report Torrent Duck by Adam Riley Trip report compiled by tour leader: Pablo Petracci Trip Report - RBL Northern Argentina 2016 2 Day 1: September 27th, 2016 – We left San Miguel de Tucumán this morning and headed towards the north-west part of the province, gaining altitude as we approached our next destination, Tafí del Valle. The road to Tafí is really interesting since it crosses three completely different habitats: wet grasslands, Yungas cloud forest, and finally, just before arriving in town, is a dry pre-Puna steppe. We made some stops along the Yungas road, looking for our first local bird specialities. Our first stop was on the bridge over Río Los Sosa, to look for one of Argentina’s endemics: Yellow-striped Brush Finch, which responded to playback right away, offering great views for everyone to enjoy and even take some pictures. We then continued further along the river and stopped at a lookout where we found our first Torrent Duck (with two chicks). We were hoping for Rufous-throated Dipper, but we had no luck this morning. Regardless, a walk Yellow-striped Brush Finch through the Alder forest and along the river shore produced by Clayton Burne some interesting sightings, including Red-tailed Comet, Mitred Parakeet, White-throated Tyrannulet, Azara´s Spinetail, Cream-winged Cinclodes, Black Phoebe, Mountain Wren, Rusty-browed Warbling Finch and Brown-capped Whitestart. We had box lunches in a camping area and took a short break before setting off for some birding in the surroundings. -

Northwest Argentina Custom Tour

Northwest Argentina With an afternoon in Buenos Aires 5 – 16 November 2009 Tour leader : Nick Athanas Report and photos : Nick Athanas This was the first of a pair of custom Northwest Argentina tours I led in the spring of 2009. It was a fairly fast-paced trip, designed that way due to limited vacation time available to some of the group. We covered a lot of ground and crammed in a lot of great sites in this beautiful and lightly populated part of the country. After a bit of bad luck early on, the tides turned in a major way with fantastic birding and a series of mega sightings in the last several days on the trip. In what was really only 11 days of birding, we saw nearly 370 species, a total more typical of a 2 to 2.5 week tour. While sleep was at a premium on this trip (the sun rose at 6:30am and set at 8:00pm), we still seemed to always stay up a bit too late enjoying a few bottles of the great local wine and some spirited conversation. Good company is always one of the key elements of a great trip, and that helped make for a very fun and successful tour! 5 November : Most people coming to Argentina fly through it’s cosmopolitan capital, Buenos Aires. Flight connections, plus the fact that the domestic airport is an hour away from the international airport, mean that many people like to spend a night in this vibrant city. This is not wasted time; even if you are not into seeing the sights of the city, since there is a fantastic bird reserve only a few miles from downtown. -

C35-MéNdez-Mojica-L

Cotinga 35 Short Communications Range extension for the Endangered Cochabamba Mountain Finch Compsospiza garleppi in Chuquisaca, Bolivia Ornithological studies in Bolivia commenced early in the 19th century, yet distributional data are still lacking for many species because many regions remain under-explored13. The southern 120 Cotinga35P-130620.indd 120 6/20/13 11:58 AM Cotinga 35 Short Communications departments of Chuquisaca, the first record of Cochabamba C. garleppi is endemic to Potosí and Tarija are biologically Mountain Finch Compsospiza Bolivia, occurring at 2,700–3,900 among the least explored areas garleppi from dpto. Chuquisaca, m in the transitional zone between of the country; they are not only c.275 km south of the closest the Inter-Andean Dry Valleys poorly known, but also possess few known locality. and Puna life zones3. Its known protected areas7,15. Here we report distribution comprises 25 localities in dptos. Cochabamba and Potosí3,9. It inhabits semi-humid montane scrub, in valleys with ravines and scattered Polylepis and Alnus trees. Cochabamba Mountain Finch is listed as Endangered, owing to continued habitat loss within its small and fragmented range3. On 13 August 2012, near the locality of Órganos Punta, Chuquisaca, in south-central Bolivia (20º17’S 64º52’W; Fig. 1), we observed two C. garleppi (presumably a pair) in a ravine, flying fast between small bushes and perching for a few seconds (Fig. 2). The birds fed briefly on the ground and then disappeared. The ravine where the observation was made is in the Boliviano-Tucumano Ceja de Monte scrublands (e.g. Baccharis sp., Echinopsis sp., Salvia sp.), just above the Ceja de Monte subhumid-humid woodland (including Polylepis crista-galli), within the transitional zone between semi-humid puna and the Inter-Andean Dry Valleys12,14. -

1996 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals

The tUCN Species Survival Commission 1996 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals Compiled and Edited by Jonathan Baillie and Brian Groombridge The Worid Conseivation Union 9 © 1996 International Union for Conservation ot Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational and otfier non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is cited and the copyright holder receives a copy of the reproduced material. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of lUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: lUCN 1996. 1996 lUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. lUCN, Gland, Switzerland. ISBN 2-8317-0335-2 Co-published by lUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge U.K., and Conservation International, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. Available from: lUGN Publications Services Unit, 219c Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CBS ODL, United Kingdom. Tel: + 44 1223 277894; Fax: + 44 1223 277175; E-mail: [email protected]. A catalogue of all lUCN publications can be obtained from the same address. Camera-ready copy of the introductory text by the Chicago Zoological Society, Brookfield, Illinois 60513, U.S.A. Camera-ready copy of the data tables, lists, and index by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 21 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 ODL, U.K.