Making the Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Fernando Botero

36 The Art of Fernando Botero ART The Art of Fernando Botero By Sarah Moody useums are afraid to show works that “Mreveal the truth.” So claimed Professor Peter Selz in a lecture inspired by the exhibition of Colombian artist Fernando Botero’s “Abu Ghraib” series organized by the Center for Latin American Studies last spring. The University of California, Berkeley was the fi rst public institution in the United States to show the powerful series. The approximately 100 drawings and oil paintings resulted from Botero’s shock and rage at what had happened at that Iraqi prison. As part of a series of talks related to the exhibit, Selz examined Botero’s development as an artist in relation to topics of violence and considered the importance of the paintings today. York. New Gallery, Image courtesy of Marlborough Botero. © Fernando Professor Selz began with a discussion of Botero’s artistic development. After winning second prize in the Salón de Artistas Colombianos in 1952, Botero used his winnings to travel to Europe to study the Old Masters. He began in Spain, copying the work of El Greco, Velázquez and Goya. In Florence, he studied the location of generously- proportioned, verisimilar bodies in real spaces, focusing especially on the work of Masaccio and Piero della Francesca “Pear” by Fernando Botero, 1976. and the sensuality of Rubens. Botero then visited the Sistine ceiling in Rome before traveling to Mexico and turning not always approach the originals almost deranged expression in place to the famous muralists Diego Rivera reverentially. According to Selz, Botero of the original’s calm smile. -

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020 James MacDevitt, M.A. Associate Professor of Art History and Visual & Cultural Studies Director, Cerritos College Art Gallery Department of Art and Design Fine Arts and Communications Division Cerritos College January 2021 Table of Contents Title Page i Table of Contents ii Sabbatical Leave Application iii Statement of Purpose 35 Objectives and Outcomes 36 OER Textbook: Disciplinary Entanglements 36 Getty PST Art x Science x LA Research Grant Application 37 Conference Presentation: Just Futures 38 Academic Publication: Algorithmic Culture 38 Service and Practical Application 39 Concluding Statement 40 Appendix List (A-E) 41 A. Disciplinary Entanglements | Table of Contents 42 B. Disciplinary Entanglements | Screenshots 70 C. Getty PST Art x Science x LA | Research Grant Application 78 D. Algorithmic Culture | Book and Chapter Details 101 E. Just Futures | Conference and Presentation Details 103 2 SABBATICAL LEAVE APPLICATION TO: Dr. Rick Miranda, Jr., Vice President of Academic Affairs FROM: James MacDevitt, Associate Professor of Visual & Cultural Studies DATE: October 30, 2018 SUBJECT: Request for Sabbatical Leave for the 2019-20 School Year I. REQUEST FOR SABBATICAL LEAVE. I am requesting a 100% sabbatical leave for the 2019-2020 academic year. Employed as a fulltime faculty member at Cerritos College since August 2005, I have never requested sabbatical leave during the past thirteen years of service. II. PURPOSE OF LEAVE Scientific advancements and technological capabilities, most notably within the last few decades, have evolved at ever-accelerating rates. Artists, like everyone else, now live in a contemporary world completely restructured by recent phenomena such as satellite imagery, augmented reality, digital surveillance, mass extinctions, artificial intelligence, prosthetic limbs, climate change, big data, genetic modification, drone warfare, biometrics, computer viruses, and social media (and that’s by no means meant to be an all-inclusive list). -

Formalism Post- Formalism

FORMALISM POST- FORMALISM nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities 7 affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2014 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren SUBMISSIONS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. 1 ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. -

PART IV CATALOGUES of Exhibitions,734 Sales,735 and Bibliographies

972 “William Blake and His Circle” PART IV CATALOGUES of Exhibitions,734 Sales,735 and Bibliographies 1780 The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, M.DCC.LXXX. The Twelfth (1780) <BB> B. Anon. "Catalogue of Paintings Exhibited at the Rooms of the Royal Academy", Library of the Fine Arts, III (1832), 345-358 (1780) <Toronto>. In 1780, the Blake entry is reported as "W Blake.--315. Death of Earl Goodwin" (p. 353). REVIEW Candid [i.e., George Cumberland], Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, 27 May 1780 (includes a criticism of “the death of earl Goodwin, by Mr. Blake”) <BB #1336> 734 Some exhibitions apparently were not accompanied by catalogues and are known only through press-notices of them. 735 See G.E. Bentley, Jr, Sale Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013 put online on 21 Aug 2013 [http://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special collections/bentley blake collection/in]. It includes sales of contemporary copies of Blake’s books and manuscripts, his watercolours and drawings, and books (including his separate prints) with commercial engravings. After 2012, I do not report sale catalogues which offer unremarkable copies of books with Blake's commercial engravings or Blake's separate commercial prints. 972 973 “William Blake and His Circle” 1784 The Exhibition of the Royal Academy, M.DCC.LXXXIV. The Sixteenth (London: Printed by T. Cadell, Printer to the Royal Academy) <BB> Blake exhibited “A breach in a city, the morning after a battle” and “War unchained by an angel, Fire, Pestilence, and Famine following”. REVIEW referring to Blake Anon., "The Exhibition. Sculpture and Drawing", Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, Thursday 27 May 1784, p. -

NATHAN OLIVEIRA Figural Variants

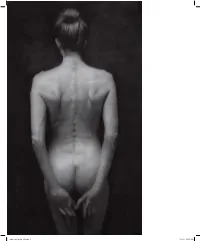

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NATHAN OLIVEIRA Figural Variants April 1- May 8, 2021 540 Ramona Street Palo Alto, CA Nathan Oliveira, Imi #3, 1990, 20 x 16 inches, oil on canvas Pamela Walsh Gallery is pleased to present Nathan Oliveira: Figural Variants, an exploration of Oliveira’s visual language as it evolved through his dedicated study of the figure. Associated with the Bay Area Figurative Movement, he was amongst artists who returned to figural subjects after the explosion of Abstract Expressionism swept through New York in the 40s and 50s. Oliveira’s work was rooted in his fascination with abstracting the human form while rendering it with a sense of honesty. He regularly worked with live models, learning their forms through repeated observation and conjuring figural variants through a diversity of mediums. Throughout his extensive career, Oliveira developed his artistic practice to flow seamlessly across multiple disciplines into one continuous voice. We are delighted to share a selection of paintings, sculptures, and prints from 1975 – 2007, highlighting his mastery of the human figure. A key figure in American Art,Nathan Oliveira (1928-2010) was a persistently individualistic artist who took his own path in defiance of the ideology of the time. With an unshakable concern for the figure, Oliveira was a prominent member of the Bay Area Figurative Movement, along with Richard Diebenkorn, David Park, Elmer Bischoff and others. A resident of Palo Alto, he taught at Stanford University for 32 years as a Professor of Studio Art. In 1959, Oliveira gained early fame as a painter, when four of his works were selected by Peter Selz for his curatorial debut exhibition, New Images of Man, at the Museum of Modern Art in NY. -

Zeller Int All 6P V2.Indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM the FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK

zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 1 11/4/16 12:23 PM THE FIGURATIVE ARTIST’S HANDBOOK A CONTEMPORARY GUIDE TO FIGURE DRAWING, PAINTING, AND COMPOSITION ROBERT ZELLER FOREWORD BY PETER TRIPPI AFTERWORD BY KURT KAUPER MONACELLI STUDIO zeller_int_all_6p_v2.indd 2-3 11/4/16 12:23 PM Copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER and THE MONACELLI PRESS Illustrations copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER unless otherwise noted Text copyright © 2016 ROBERT ZELLER Published in the United States by MONACELLI STUDIO, an imprint of THE MONACELLI PRESS All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Zeller, Robert, 1966– author. Title: The figurative artist’s handbook : a contemporary guide to figure drawing, painting, and composition / Robert Zeller. Description: First edition. | New York, New York : Monacelli Studio, 2016. Identifiers: LCCN 2016007845 | ISBN 9781580934527 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Figurative drawing. | Figurative painting. | Human figure in art. | Composition (Art) | BISAC: ART / Techniques / Life Drawing. | ART / Techniques / Drawing. | ART / Subjects & Themes / Human Figure. Classification: LCC NC765 .Z43 2016 | DDC 743.4--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016007845 ISBN 978-1-58093-452-7 Printed in China Design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover design by JENNIFER K. BEAL DAVIS Cover illustrations by ROBERT ZELLER Illustration credits appear on page 300. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is dedicated to my daughter, Emalyn. First Edition This book was inspired by Kenneth Clark's The Nude and Andrew Loomis's Figure Drawing for All It's Worth. MONACELLI STUDIO This book would not have been possible without the help of some important peo- THE MONACELLI PRESS 236 West 27th Street ple. -

Sean Scully: Inside Outside Media Release

Sean Scully: Inside Outside Media Release Longside Gallery and Open Air 29 September 2018–6 January 2019 “I have spent my life making the melancholic into something irresistible. Because the world has changed around me and become more regretful, my paintings have become more true.” Sean Scully Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP) presents Sean Scully: Inside Outside, the largest-ever presentation of sculptures and first exhibition of sculpture and painting in the UK by the Irish-born artist. Exploring concepts of landscape and abstraction with human experience, the exhibition unites sculpture with important recent paintings on aluminium, together with works on paper. Drawing out ideas pertinent to the singularity of YSP and its landscape, this is a poetic, robust experience that embraces the Park’s topography and Scully’s exceptional vigour, as well as his belief that in life and art there is perpetual discovery. The exhibition presents an artist at the height of his powers. Aged 72, it is evident that there is no curtailment of Scully’s energy, drive and vision. Keenly aware of the labour that dominated the lives of his mining family, Scully’s practice is one of great rigour and toil, his output prodigious. For YSP he has made new paintings and sculpture – resolutely contemporary works that integrate an inclination towards geometry with the romantic sincerity of landscape painting in the historical tradition. Born in Dublin in 1945, raised in London, and now resident in New York, London and Germany, Scully is considered to be one of the most important abstract painters working today. Drawing on European traditions but with the distinct character and scale prevalent Shadow Stack, 2018 and Landline Inwards, 2015 in the USA, Scully is credited with reinvigorating abstract painting. -

Path to Equilibrium Foozhan Kashkooli Winthrop University

Winthrop University Digital Commons @ Winthrop University Graduate Theses The Graduate School 5-2015 Path to Equilibrium Foozhan Kashkooli Winthrop University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses Part of the Art and Design Commons, and the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Kashkooli, Foozhan, "Path to Equilibrium" (2015). Graduate Theses. 3. https://digitalcommons.winthrop.edu/graduatetheses/3 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Winthrop University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PATH TO EQUILIBRIUM A Thesis Statement Presented to the Faculty of the College of Visual and Performing Arts In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Degree Of Master of Fine Arts In the Department of Fine Arts Winthrop University May 2015 By Foozhan Kashkooli Abstract This statement outlines the theoretical, historical, and conceptual influences that shape my Master of Fine Arts thesis at Winthrop University. It further describes and analyzes the series of paintings that compose my thesis Equilibrium, each one a reflection of my aesthetic experience as I evolved as an artist. As I will illustrate, the aesthetic experiences reflected in my work are intertwined with the artist or movement that inspired me at the time. The series consists of seven large-scale, abstract paintings, where I explore balancing form, shape, and color. In this thesis statement, I am asserting my progression as an evolving artist and elucidating my investigation of painting as a unique medium with its own complexity of composition and arrangements of shape, form, and color. -

Art and Technology

LEON4102_pp169-174.ps - 3/11/2008 12:37 PM From Technophilia to Technophobia: The Impact of the Vietnam War on the Reception ABSTRACT Using the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s 1971 exhibition REFRESH! CONFERENCE PAPERS of “Art and Technology” “Art and Technology” as a case study, this essay examines a shift in attitude on the part of influential American artists and critics toward collaborations Anne Collins Goodyear between art and technology from one of optimism in the mid- 1960s to one of suspicion in the early 1970s. The Vietnam War dramatically undermined public confidence in the promise of new technology, linking it with corporate support of the war. Technology is not art—not invention. It is a simultaneous hope and technology. In response to the Ultimately, the discrediting of and hoax. Technology is what we do to the Black Panthers perceived Soviet threat, American industry-sponsored technology and the Vietnamese under the guise of advancement in a mate- education emphasized science and not only undermined the prem- ises of the LACMA exhibition rialistic theology. technology, while influential theo- but also may have contributed rists such as C.P. Snow, Reyner —Richard Serra [1] to the demise of the larger “art Banham and Marshall McLuhan and technology” movement in stressed the need for interconnec- the United States. In September 1970 artist James Turrell made a prophetic re- tion between art, science and tech- mark about Maurice Tuchman’s “Art and Technology” exhi- nology [5]. In 1967, engineer Billy bition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Klüver, co-founder of Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), argued that “the new inter- You could make this thing [“Art and Technology”] historically face between artists and engineers . -

The Early Works of Maria Nordman by Laura Margaret

In Situ and On Location: The Early Works of Maria Nordman by Laura Margaret Richard A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Julia Bryan-Wilson, Chair Professor Whitney Davis Professor Shannon Jackson Associate Professor Jeffrey Skoller Summer 2015 Abstract In Situ and On Location: The Early Works of Maria Nordman by Laura Margaret Richard Doctor of Philosophy in History of Art and the Designated Emphasis in Film Studies University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Julia Bryan-Wilson, Chair This dissertation begins with Maria Nordman’s early forays into capturing time and space through photography, film, and performance and it arrives at the dozen important room works she constructed between 1969 and 1979. For these spaces in Southern California, the San Francisco Bay Area, Italy, and Germany, the artist manipulated architecture to train sunshine into specific spatial effects. Hard to describe and even harder to illustrate, Nordman’s works elude definition and definitiveness, yet they remain very specific in their conception and depend on precision for their execution. Many of these rooms were constructed within museums, but just as many took place in her studio and in other storefronts in the working-class neighborhoods of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Milan, Genoa, Kassel, and Düsseldorf. If not truly outside of the art system then at least on its fringes, these works were premised physically and conceptually on their location in the city. -

Moderne Kunst

Auktion 303 14./15. Juli 2021 karlundfaber.de Moderne Kunst 7.2021 KARL & FABER 1 2 KARL & FABER 7.2021 7.2021 KARL & FABER 3 Auktion 303 14./15. Juli 2021 KARL & FABER Kunstauktionen · Amiraplatz 3 · 80333 München Moderne Kunst Modern Art INHALT / INDEX Wassily Kandinsky, Titelholzschnitt für den Almanach Der Blaue Reiter, Los 500 LOS / LOT 500 – 553 Teil I – Ausgewählte Werke / Part I – Selected Works S. 17 Vorherige Seite: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paysage avec femme assise au milieu, Los 506 LOS / LOT 600 – 801 Teil II / Part II S. 139 Emil Nolde, „Meer“ (Welle), Los 522 Gabriele Münter, Bei Gärtnerei Mederer (?) Murnau, Los 529 Edvard Munch, Der Kuss IV, Los 501 Hans Hartung, T-1970-H37, Los 551 KONTAKT KARL & FABER MÜNCHEN / CONTACT KARL & FABER MUNICH TERMINE DATES Mittwoch, 14. Juli 2021 – Auktionen 303/304 Wednesday, 14 July 2021 – Auctions 303/304 Moderne & Zeitgenössische Kunst Modern & Contemporary Art KARL & FABER Kunstauktionen 14 Uhr Moderne Kunst Teil II Los 600–801 2 pm Modern Art Part II Lot 600–801 Amiraplatz 3 · Luitpoldblock 16.30 Uhr Zeitgenössische Kunst Teil II Los 1000–1247 4.30 pm Contemporary Art Part II Lot 1000–1247 80333 München · Germany T +49 89 22 18 65 Donnerstag, 15. Juli 2021 – Auktionen 303/304/305 Thursday, 15 July 2021 – Auctions 303/304/305 F +49 89 22 83 350 Sonderauktion „WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC“ Special auction „WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC“ [email protected] Moderne & Zeitgenössische Kunst – Ausgewählte Werke Modern & Contemporary Art – Selected Works 15.30 Uhr WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC Los 2100–2208 3.30 pm WEISS WHITE BIANCO BLANC Lot 2100–2208 ÖFFENTLICH BESTELLTE UND VEREIDIGTE AUKTIONATOREN / PUBLICLY APPOINTED AND SWORN AUCTIONEERS 18 Uhr Moderne Ausgewählte Werke Los 500–553 6 pm Modern Art – Selected Works Lot 500–553 19 Uhr Zeitgenössische Ausgewählte Werke Los 900–950 7 pm Contemporary Art – Selected Works Lot 900–950 Dr. -

Art on Mars: a Foundation for Exoart

THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA AUSTRALIA by TREVOR JOHN RODWELL Bachelor of Design (Hons), University of South Australia Graduate Diploma (Business Enterprise), The University of Adelaide ART ON MARS: A FOUNDATION FOR EXOART May 2011 ABSTRACT ART ON MARS: A FOUNDATION FOR EXOART It could be claimed that human space exploration started when the former Soviet Union (USSR) launched cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin into Earth orbit on 12 April 1961. Since that time there have been numerous human space missions taking American astronauts to the Moon and international crews to orbiting space stations. Several space agencies are now working towards the next major space objective which is to send astronauts to Mars. This will undoubtedly be the most complex and far-reaching human space mission ever undertaken. Because of its large scale and potentially high cost it is inevitable that such a mission will be an international collaborative venture with a profile that will be world- wide. Although science, technology and engineering have made considerable contributions to human space missions and will be very much involved with a human Mars mission, there has been scant regard for artistic and cultural involvement in these missions. Space agencies have, however, realised the influence of public perception on space funding outcomes and for some time have strived to engage the public in these space missions. This has provided an opportunity for an art and cultural involvement, but there is a problem for art engaging with space missions as currently there is no artform specific to understanding and tackling the issues of art beyond our planet.