Agrest Conway Weisman Eds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tectonics and the Space of Communicativity

91st ACSA INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE • HELSINKI • JULY 27-30, 2003 423 Tectonics and The Space of Communicativity DORIAN WISZNIEWSKI University of Edinburgh It is a logical corollary to post-modernity’s skepticism, that architecture’s role, privileged since the Renaissance to make generalising plans for society in general, should be called into question. Let us remember Lyo- tard’s optimism, that ‘‘invention is always born of dissension’’1 . However, we must also be wary of post modernity’s skepticism. It might lead to an ideological revolution where we simply supplant materialism for idealism, where either the utilitarian or sensual experi- ence is promoted to the denial of meaning. This would be a denial of architecture’s representational character and therefore a denial of its contingent relation to regimes of power, politics and philosophy. We must also be wary of simply asserting the worth of fragmentation and collision as the empty rhetoric of a new political dynamics of resistance. This could have the outcome of Fig. 1. Frank O. Gehry, Guggenheim, Bilbao, 1991-97. solipsism, which if not an outright dismissal, certainly is a sublimation of the everyday conditions of co-existence tectonics in this way already invokes proximity to word in the life-world. To be sure, in post-modernity it might language. The architectural theorists Diana Agrest and be difficult to understand what is architecture’s role, Mario Gandelsonas declared the production of architec- indeed what it represents. For some, architecture, or ture as the production of knowledge. They also specu- building that promotes itself as architecture, especially lated into architectural semiotics, thus making direct bombastically to the eclipse of all else, stands already as links between the themes of power, knowledge and a symbol of the old orders. -

Tes 3 the Mother of All Bombs

75 Nigel Coates 3 The Mother of all Bombs Freya Wigzell 8 The people here think I’m out of my mind Kristina Jaspers 20 The Adam’s Family Store Claire Zimmerman 28 Albert Kahn in the Second Industrial Revolution Laila Seewang 45 Ernst Litfaß and the Trickle-Down Effect Roberta Marcaccio 59 The Hero of Doubt Rebecca Siefert 71 Lauretta Vinciarelli, Illuminated Shantel Blakely 86 Solid Vision, or Mr Gropius Builds his Dream House Thomas Daniell 98 In Conversation with Shin Takamatsu Francesco Zuddas 119 The Idea of the Università Joanna Merwood-Salisbury 132 This is not a Skyscraper Victor Plahte Tschudi 150 Piranesi, Failed Photographer Francisco González de Canales 152 Eladio and the Whale Ross Anderson 163 The Appian Way Salomon Frausto 183 Sketches of a Utopian Pessimist Theo Crosby 189 The Painter as Designer Marco Biraghi 190 Poelzig and the Golem Zoë Slutzky 202 Dino Buzzati’s Ideal House 206 Contributors 75 224674_AA_75_interior.indd 1 22/11/2017 09:54 aa Files The contents of aa Files are derived from the activities Architectural Association of the Architectural Association School of Architecture. 36 Bedford Square Founded in 1847, the aa is the uk’s only independent London wc1b 3es school of architecture, offering undergraduate, t +44 (0)20 7887 4000 postgraduate and research degrees in architecture and f +44 (0)20 7414 0782 related fields. In addition, the Architectural Association aaschool.ac.uk is an international membership organisation, open to anyone with an interest in architecture. Publisher The Architectural Association -

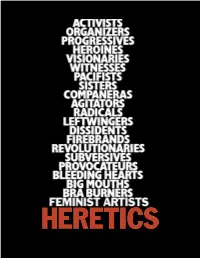

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Liberalizing Art. Evidence on the Impressionists at the End of the Paris Salon

European Journal of Political Economy 62 (2020) 101857 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Journal of Political Economy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ejpe Liberalizing art. Evidence on the Impressionists at the end of the Paris Salon Federico Etro *, Silvia Marchesi, Elena Stepanova University of Florence, University of Milan Bicocca and St. Anna School of Advanced Studies-Pisa, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT JEL classification: We analyze the art market in Paris between the government-controlled Salon and the post-1880 C23 system, when the Republican government liberalized art exhibitions. The jury of the old Salon Z11 decided on submissions with a bias in favor of conservative art of the academic insiders, erecting Keywords: entry barriers against outsiders as the Impressionists. With a difference-in difference estimation, Art market we provide evidence that the end of the government-controlled Salon contributed to start the price Liberalization increase of the Impressionists relative to the insiders. Market structure Insider-outsider Hedonic regressions Impressionism 1. Introduction For more than two centuries the Paris Salon organized the art exhibition where French artists selected by an official jury could display their works. Such a system controlled by the on-going regime ended with the liberalization of 1880, which started the creation of a variety of privately organized salons. The artistic innovations of Impressionist painters, such as Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Edgar Degas, Paul Cezanne as well as Edouard Manet, had been marginalized in the government- controlled Salon and in the Paris art market, which were dominated by more traditional Academic artists. -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s........................................................................... -

Review of the Year 2012–2013

review of the year TH E April 2012 – March 2013 NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY review of the year April 2012 – March 2013 published by order of the trustees of the national gallery london 2013 Contents Introduction 5 Director’s Foreword 6 Acquisitions 10 Loans 30 Conservation 36 Framing 40 Exhibitions 56 Education 57 Scientific Research 62 Research and Publications 66 Private Support of the Gallery 70 Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 74 Financial Information 74 National Gallery Company Ltd 76 Fur in Renaissance Paintings 78 For a full list of loans, staff publications and external commitments between April 2012 and March 2013, see www.nationalgallery.org.uk/about-us/organisation/ annual-review the national gallery review of the year 2012– 2013 introduction The acquisitions made by the National Gallery Lucian Freud in the last years of his life expressed during this year have been outstanding in quality the hope that his great painting by Corot would and so numerous that this Review, which provides hang here, as a way of thanking Britain for the a record of each one, is of unusual length. Most refuge it provided for his family when it fled from come from the collection of Sir Denis Mahon to Vienna in the 1930s. We are grateful to the Secretary whom tribute was paid in last year’s Review, and of State for ensuring that it is indeed now on display have been on loan for many years and thus have in the National Gallery and also for her support for very long been thought of as part of the National the introduction in 2012 of a new Cultural Gifts Gallery Collection – Sir Denis himself always Scheme, which will encourage lifetime gifts of thought of them in this way. -

Queer Geographies

Queer Geographies BEIRUT TIJUANA COPENHAGEN Lasse Lau Mirene Arsanios Felipe Zúñiga-González Mathias Kryger Omar Mismar Museet for Samtidskunst, Roskilde, Denmark Queer Geographies Copyright ©!2013 Bunnylau, the artists and the authors All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Editors Lasse Lau Mirene Arsanios Felipe Zúñiga-González Mathias Kryger Design Omar Mismar Printed in the United States by McNaughton & Gunn, Inc Copy editor Emily Votruba Translators Masha Refka John Pluecker Tamara Manzo Sarah Lookofsky Michael Lee Burgess Lotte Hoelgaard Christensen Cover photo by Flo Maak ISBN 978-87-90690-30-4 Funded in part by The Danish Arts Council Published by Museet for Samtidskunst // Museum of Contemporary Art Stændertorvet 3D DK- 4000 Roskilde Denmark A Queer Geographer’s Life as an Introduction to Queer Theory, Space, and Time Jen Jack Gieseking Environmental Psychology, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York I used to be afraid to get in bed with theory, and queer the volume was as if she were turning over the material theory was no diferent. What the hell were these theory apparition of a queer secret. What lay inside charmed me people talking about? Who could ever capture queer life and stuck with me. LGBTQ geographies and geographies in theory? As an urban, queer, feminist geographer and of sexuality were not only existent, they were exciting and psychologist, as well as a lesbian-queer-dyke-feminist- important stuf. It would be another decade before I took trans non-op, non-hormone dyke, I have had to come to up LGBTQ geographies again, exploring other passions grips with theory, queer and otherwise. -

Purcell IAWA Archivist Report 2012-2013 Draft.Docx.Docx

1 Archivist’s Report, FY 2013-2014 International Archives of Women in Architecture (IAWA) By Aaron D. Purcell Director of Special Collections and IAWA Archivist Overview During the past year, Special Collections continued its joint partnership with the College of Architecture and Urban Studies to acquire, arrange, describe, provide access to, and promote IAWA collections. Sherrie Bowser led the effort to process, acquire, and promote IAWA collections. With the help of students and other staff she accessioned 8 new collections and processed 6 collections. In spring 2014, Sherrie Bowser moved on to another professional position in Illinois. In October 2014, Samantha Winn began work as Collections Archivist, with responsibilities for IAWA collections. Collection Highlights ● Special Collections received 8 new IAWA collections during the past year, totaling 18.2 cubic feet of material and more than 274 Mb of digital photographs. (See Appendix 1, Acquired Accessions) ● With the help of staff, 7 IAWA collections were processed over the past year, totaling 33.6 cubic feet. (See Appendix 2, Processed Collections) ● There are now approximately 425 distinct IAWA collections totaling 1,787 cubic feet. ● Made 13 book purchases that that directly support IAWA collections (See Appendix 3, New Purchases) ● Spring 2014, visit to Linda Kiisk in Sacramento, California to appraise and ship back her collection to Virginia Tech Research, Promotion, and Selected Uses of IAWA Collections ● Held open house and sponsored exhibit for the 50th Anniversary of CAUS, Fall 2014 ● Assisted Robert Holton, Milka Bliznakov Research Prize winner, with onsite research on the role and contribution of Natalie de Blois in the design of three SOM projects (Lever House, Pepsi-Cola Headquarters, and Union Carbide) completed in New York City between 1950-1960 ● Exhibit in Special Collections, IAWA: Examples of women’s opportunities in architecture and design education, 1865-1993,” Fall 2013 ● Assisted Donna Dunay’s 1st year studio class (ca. -

Seduced Copies of Measured Drawings Written

m Mo. DC-671 .-£• lshlH^d)lj 1 •——h,— • ULU-S-S( f^nO District of Columbia arj^j r£Ti .T5- SEDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Building Survey National Park Service Department of the Interior" Washington, D.C 20013-7127 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY DUMBARTON OAKS PARK HABS No. DC-571 Location: 32nd and R Sts., NW, Washington, District of Columbia. The estate is on the high ridge that forms the northern edge of Georgetown. Dumbarton Oaks Park, which was separated from the formal gardens when it was given to the National Park Service, consists of 27.04 acres designed as the "naturalistic" component of a total composition which included the mansion and the formal gardens. The park is located north of and below the mansion and the terraced formal gardens and focuses on a stream valley sometimes called "The Branch" (i.e., of Rock Creek) nearly 100' below the mansion. North of the stream the park rises again in a northerly and westerly direction toward the U.S. Naval Observatory. The primary access to the park is from R Street between the Dumbarton Oaks estate and Montrose Park along a small lane presently called Lovers' Lane. Present Owner; Dumbarton Oaks Park is a Federal park, owned and maintained by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior. Dates of Construction: Dumbarton Oaks estate was acquired by Robert Woods Bliss and Mildred Barnes Bliss in 1920. At their request, Beatrix Jones Farrand, a well- known American landscape architect, agreed to undertake the design and oversee the maintenance of the grounds. -

Fall/Winter 2018

FALL/WINTER 2018 Yale Manguel Jackson Fagan Kastan Packing My Library Breakpoint Little History On Color 978-0-300-21933-3 978-0-300-17939-2 of Archeology 978-0-300-17187-7 $23.00 $26.00 978-0-300-22464-1 $28.00 $25.00 Moore Walker Faderman Jacoby Fabulous The Burning House Harvey Milk Why Baseball 978-0-300-20470-4 978-0-300-22398-9 978-0-300-22261-6 Matters $26.00 $30.00 $25.00 978-0-300-22427-6 $26.00 Boyer Dunn Brumwell Dal Pozzo Minds Make A Blueprint Turncoat Pasta for Societies for War 978-0-300-21099-6 Nightingales 978-0-300-22345-3 978-0-300-20353-0 $30.00 978-0-300-23288-2 $30.00 $25.00 $22.50 RECENT GENERAL INTEREST HIGHLIGHTS 1 General Interest COVER: From Desirable Body, page 29. General Interest 1 The Secret World Why is it important for policymakers to understand the history of intelligence? Because of what happens when they don’t! WWI was the first codebreaking war. But both Woodrow Wilson, the best educated president in U.S. history, and British The Secret World prime minister Herbert Asquith understood SIGINT A History of Intelligence (signal intelligence, or codebreaking) far less well than their eighteenth-century predecessors, George Christopher Andrew Washington and some leading British statesmen of the era. Had they learned from past experience, they would have made far fewer mistakes. Asquith only bothered to The first-ever detailed, comprehensive history Author photograph © Justine Stoddart. look at one intercepted telegram. It never occurred to of intelligence, from Moses and Sun Tzu to the A conversation Wilson that the British were breaking his codes. -

News from Garden Landscape Studies

Landscape Matters: News from GLS, Fall 2011 The Garden and Landscape Studies program at Dumbarton Oaks is pleased to share with you the following announcements regarding 2011-12 fellows, fellowship applications, new programs, forthcoming lectures and symposium, and new publications. GLS 2010-11 fellows in “Easy Rider,” the installation by contemporary artist Patrick Dougherty in the Ellipse. Image courtesy Nathaniel P. VanValkenburgh. Survey of Former Fellows First, we would like to thank all the former fellows, project grant recipients, and senior fellows who took the time to complete the survey we circulated in anticipation of the 40th anniversary of the Garden and Landscape Studies program. We are now considering how best to share this information among all of you. Meanwhile, you might be interested in a few general observations. Nearly all respondents expressed appreciation for the time, space, and resources that Dumbarton Oaks provides for scholars in garden history and landscape studies. Many of you remarked on the uniqueness of our program, offering residential facilities in the context of a fabulous garden and an extraordinary library. Quite a few of you noted that the program covers virtually limitless chronological, geographical, and disciplinary fields, and is addressed to academics and design professionals alike. For some of you, this breadth exposes a fault line in the program—as in the larger field—between history and practice. Some of you thought GLS ought to be more attentive to one or the other, while others insisted the distinctive mission of the program was to provide a bridge between the two. The origins of this fault line lie deep in the history of program. -

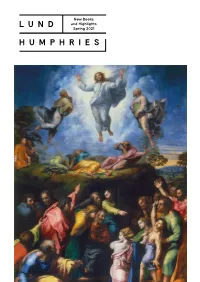

New Books and Highlights Spring 2021 Welcome

New Books and Highlights Spring 2021 Welcome Visions of Heaven: Dante and the Art of Divine Light by Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp is a glorious highlight of our Spring 2021 programme, published to coincide with the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death. It is both a feast for the eyes, lavishly illustrated with masterpieces of Renaissance and Baroque painting, and a hugely original study of the impact of Dante’s vision of divine light on the artists of the Renaissance and Baroque. It is also the trailblazer for a new Lund Humphries programme of illustrated Art History books written by scholars and accessible to non-specialists. Keep an eye out in our newsletters and on our social-media channels for two new Art History series launching in Autumn 2021: Illuminating Women Artists: Renaissance and Baroque, and Northern Lights. A number of books in our Spring list uncover aspects of Design History from the more recent past. The IBM Poster Program tells a fascinating story of mid-century graphic design centred on one of the most important corporations of the 20th century; designer Greta Magnusson Grossman’s previously untold contribution to mid-century modernism is charted in an important new monograph on her work; and Arts and Crafts Pioneers explores the importance of the Victorian Century Guild of Artists and its influential periodical, The Hobby Horse, in the formation of the Arts & Crafts Movement. A growing strand of the Lund Humphries publishing programme is concerned with the interaction between contemporary visual culture and the contemporary world. The New Directions in Contemporary Art series, edited by Marcus Verhagen, launches this Spring with four thought-provoking critical texts.