Lauretta Vinciarelli James Luna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tes 3 the Mother of All Bombs

75 Nigel Coates 3 The Mother of all Bombs Freya Wigzell 8 The people here think I’m out of my mind Kristina Jaspers 20 The Adam’s Family Store Claire Zimmerman 28 Albert Kahn in the Second Industrial Revolution Laila Seewang 45 Ernst Litfaß and the Trickle-Down Effect Roberta Marcaccio 59 The Hero of Doubt Rebecca Siefert 71 Lauretta Vinciarelli, Illuminated Shantel Blakely 86 Solid Vision, or Mr Gropius Builds his Dream House Thomas Daniell 98 In Conversation with Shin Takamatsu Francesco Zuddas 119 The Idea of the Università Joanna Merwood-Salisbury 132 This is not a Skyscraper Victor Plahte Tschudi 150 Piranesi, Failed Photographer Francisco González de Canales 152 Eladio and the Whale Ross Anderson 163 The Appian Way Salomon Frausto 183 Sketches of a Utopian Pessimist Theo Crosby 189 The Painter as Designer Marco Biraghi 190 Poelzig and the Golem Zoë Slutzky 202 Dino Buzzati’s Ideal House 206 Contributors 75 224674_AA_75_interior.indd 1 22/11/2017 09:54 aa Files The contents of aa Files are derived from the activities Architectural Association of the Architectural Association School of Architecture. 36 Bedford Square Founded in 1847, the aa is the uk’s only independent London wc1b 3es school of architecture, offering undergraduate, t +44 (0)20 7887 4000 postgraduate and research degrees in architecture and f +44 (0)20 7414 0782 related fields. In addition, the Architectural Association aaschool.ac.uk is an international membership organisation, open to anyone with an interest in architecture. Publisher The Architectural Association -

Purcell IAWA Archivist Report 2012-2013 Draft.Docx.Docx

1 Archivist’s Report, FY 2013-2014 International Archives of Women in Architecture (IAWA) By Aaron D. Purcell Director of Special Collections and IAWA Archivist Overview During the past year, Special Collections continued its joint partnership with the College of Architecture and Urban Studies to acquire, arrange, describe, provide access to, and promote IAWA collections. Sherrie Bowser led the effort to process, acquire, and promote IAWA collections. With the help of students and other staff she accessioned 8 new collections and processed 6 collections. In spring 2014, Sherrie Bowser moved on to another professional position in Illinois. In October 2014, Samantha Winn began work as Collections Archivist, with responsibilities for IAWA collections. Collection Highlights ● Special Collections received 8 new IAWA collections during the past year, totaling 18.2 cubic feet of material and more than 274 Mb of digital photographs. (See Appendix 1, Acquired Accessions) ● With the help of staff, 7 IAWA collections were processed over the past year, totaling 33.6 cubic feet. (See Appendix 2, Processed Collections) ● There are now approximately 425 distinct IAWA collections totaling 1,787 cubic feet. ● Made 13 book purchases that that directly support IAWA collections (See Appendix 3, New Purchases) ● Spring 2014, visit to Linda Kiisk in Sacramento, California to appraise and ship back her collection to Virginia Tech Research, Promotion, and Selected Uses of IAWA Collections ● Held open house and sponsored exhibit for the 50th Anniversary of CAUS, Fall 2014 ● Assisted Robert Holton, Milka Bliznakov Research Prize winner, with onsite research on the role and contribution of Natalie de Blois in the design of three SOM projects (Lever House, Pepsi-Cola Headquarters, and Union Carbide) completed in New York City between 1950-1960 ● Exhibit in Special Collections, IAWA: Examples of women’s opportunities in architecture and design education, 1865-1993,” Fall 2013 ● Assisted Donna Dunay’s 1st year studio class (ca. -

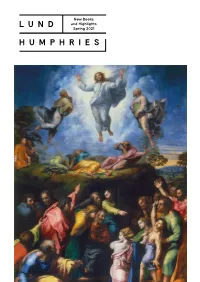

New Books and Highlights Spring 2021 Welcome

New Books and Highlights Spring 2021 Welcome Visions of Heaven: Dante and the Art of Divine Light by Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp is a glorious highlight of our Spring 2021 programme, published to coincide with the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death. It is both a feast for the eyes, lavishly illustrated with masterpieces of Renaissance and Baroque painting, and a hugely original study of the impact of Dante’s vision of divine light on the artists of the Renaissance and Baroque. It is also the trailblazer for a new Lund Humphries programme of illustrated Art History books written by scholars and accessible to non-specialists. Keep an eye out in our newsletters and on our social-media channels for two new Art History series launching in Autumn 2021: Illuminating Women Artists: Renaissance and Baroque, and Northern Lights. A number of books in our Spring list uncover aspects of Design History from the more recent past. The IBM Poster Program tells a fascinating story of mid-century graphic design centred on one of the most important corporations of the 20th century; designer Greta Magnusson Grossman’s previously untold contribution to mid-century modernism is charted in an important new monograph on her work; and Arts and Crafts Pioneers explores the importance of the Victorian Century Guild of Artists and its influential periodical, The Hobby Horse, in the formation of the Arts & Crafts Movement. A growing strand of the Lund Humphries publishing programme is concerned with the interaction between contemporary visual culture and the contemporary world. The New Directions in Contemporary Art series, edited by Marcus Verhagen, launches this Spring with four thought-provoking critical texts. -

Mana Contemporary Fall 2018 Open House

This fall, that thoughtful emphasis will distinguish Mana Contemporary a suite of transformational projects: JOHN CHAMBERLAIN: PHOTOGRAPHS An array of panoramic color shots taken by the Fall 2018 sculptor between 1989 and 2002 using with a Open House swing-lens Widelux camera DAN FLAVIN: FLUORESCENT LIGHT A large-scale installation by the Minimalist master that fills the space of Mana’s First Floor Theater with radiant color. First shown at the Institute for the Arts at Rice University in Houston, Texas, in 1972, the work appears at Mana courtesy of the Estate of Dan Flavin. BERNARD KIRSCHENBAUM A striking large-scale installation, Plywood Arc (1973) and a metal wall work, Blue Steel Parabola 1 (1971), by the American sculptor and educator ARNULF RAINER A core selection of the artist’s cross and angel paint- ings from 1985–2000, revealing the artist’s fascination with the states that accompany religious devotion FRED SANDBACK: SCULPTURE A selection of works dating from 1967–82 presented by the Ayn Foundation, incorporating a series of early corner sculptures in metal rod and elastic cord, plus later acrylic yarn works determined by their architec- tural surroundings Lauretta Vinciarelli, Incandescent Frames (Study 1), 1998. Watercolor on paper. 30 1/4 x 22 1/4 in. Private collection ANDY WARHOL: THE ORIGINAL SILKSCREENS A stunning display of iconic prints from 1967–1987, presented by the Ayn Foundation in collaboration Opening Reception: Sunday, October 14, 1–7PM with DASMAXIMUM and expanded for this iteration with an additional work -

Oz Contributors

Oz Volume 17 Article 10 1-1-1995 Contributors Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/oz This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation (1995) "Contributors," Oz: Vol. 17. https://doi.org/10.4148/2378-5853.1276 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oz by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. Contributors Richard Hansen is an assistant profes Pat Morton teaches architectural his Paul Shepheard is an architect living Lauretta Vinciarelli, born and educated sor in the Art department at the tory and theory at the University of and working in London, England. His in Rome and now based in New York University of Southern Colorado, where California, Riverside and SCI-Arc. She book "What is Architecture?" is pub City, Dr. Viciarelli has for the past five he teaches 3-d design and sculpture. has a doctorate from Princeton Univer lished by the MIT Press. He is current years been producing a remarkable Educated as a landscape architect at the sity and wrote her dissertation on the ly researching thematic landscapes body of watercolors of architectural University of Colorado (M.L.A.) and as 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris. She assisted by a grant from the Graham spaces. Her work has been exhibited in a sculptor at the College of William and writes about postcolonial theory, issues Foundation for Advanced Studies in both Europe and the United States in Mary (B.A.), his creative work centers of marginality, and contemporary ar the Fine Arts, Chicago such venues as the Archive of the around the poetics of water. -

Textbooks in Focus: Women in Architecture Survey 12:00 - 1:30Pm Wednesday, 12Th May, 2021 Category Roundtable

Textbooks in Focus: Women in Architecture Survey 12:00 - 1:30pm Wednesday, 12th May, 2021 Category Roundtable The first Roundtable of the SAH Women in Architecture Affiliate Group aims to give voice to the discussion illuminating scholarship and teaching materials on women in architecture. A remarkable number of trailblazing studies have manifested this extensive legacy. The textbooks in focus accord with the mission of the SAH Women in Architecture Affiliate Group and highlight the significant yet still scarcely explored professional contributions of women who, to a great extent, shaped the discipline around the world. Our aspiration is to introduce the volumes recently published or in production, and emphasize the names of pioneering women in architecture, who have inspired and built cultural, spiritual, and physical environments across time and place. The novelty of our vision is in presenting not only a collection of readings but in broadening the field by advancing a more incisive overview of the topic as a whole, and by intertwining an approach to the professional standing of women in architecture with the more explicit attention to related themes. By examining architectural practice, and including the craftsmanship of landscape and interior design, architectural theory, artistry and collecting, and academic and social initiatives and criticism, the presented research sets out debates, questions, and projects around women in architecture, and stimulates broader studies and discussions in emerging areas. Furthermore, it becomes a powerful catalyst for future publications on the subject and for academic surveys worldwide envisioned to educate, empower, and craft the future of the profession. The books are introduced by their authors and editors. -

Lauretta Vinciarelli, Orange Silence, 2000, Three Watercolor-On-Paper Works, Each 22 × 15"

Lauretta Vinciarelli, Orange Silence, 2000, three watercolor-on-paper works, each 22 × 15". Lauretta Vinciarelli TOTAH Solace. That’s the word that kept coming to mind as I looked at Lauretta Vinciarelli’s exacting watercolor-and-ink studies of light, space, and reflection, after not having seen art in person for six months due to the Covid-19 closures. This exquisite exhibition focused on the artist and architect’s mature production between 1984 and 2002, before her untimely death in 2011 at age sixty-eight. It seemed to pick up right where the last Vinciarelli show—at New York’s Judd Foundation in 2019—left off. That presentation surveyed her output from the years 1976 to 1986, when she was romantically involved with the foundation’s namesake. Unfortunately, the offering, as Ida Panicelli wrote in these pages, left “unaddressed the circuitous path” that Vinciarelli “took to become an extraordinary artist.” Not so here. Vinciarelli was raised in Rome, where her father was an organist at Saint Peter’s Basilica (she later likened the numbering of works in her various series to notes on a musical scale). She studied architecture at Sapienza Università di Roma before emigrating in 1969 to the United States, where she taught for many years at several institutions. In 1987, she commenced her transcendent spatial experiments in watercolor and ink, which were never meant to be plans for actual buildings. “The architectural space I have painted since 1987 does not portray solutions to specific demands of use,” she once noted. Her engagement with luminous watercolor on sturdy sheets of Fabriano paper, typically thirty by twenty-two inches, allowed her to exemplify what it means to “not portray,” to abandon utility in the service of unbridled imagination, as other well- known and mostly male avant-garde architects of the era—such as Walter Pichler and Lebbeus Woods—did. -

Erin Hogan Carl Krause (312) 443-3664 (312) 443-3363 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE April 5, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Erin Hogan Carl Krause (312) 443-3664 (312) 443-3363 [email protected] [email protected] ART INSTITUTE EXHIBITION EXPLORES COMMON CONCEPTS IN ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN ACROSS TIME AND PLACE Sharing Space Opens April 6, 2013 Features Work by Charles and Ray Eames, R. Buckminster Fuller, Hella Jongerius, Rudolf Schindler, and More A new installation drawn from the Art Institute of Chicago’s renowned collection of architecture and design explores the common ground between the two fields throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. On view April 6– August 18, 2013 in Galleries 283–285, Sharing Space: Creative Intersections in Architecture and Design showcases the depth of the collection by presenting works selected with an eye toward mutual creative concepts and strategies rather than the typical categories of media or period. By doing so, the exhibition creates exciting new “conversations” between works that are organized into six creative ideas or themes: color, geometry, structure, hybrid, surface, and technology. The result offers visitors the chance to see new and unexpected relationships among the related areas of architecture, urban planning, visual communications, and industrial design from a global mix of designers and architects spanning over a century of time. Each of the six sections of the exhibition illuminates underlying formal or conceptual concepts in what might first seem to be disparate works. The use of color to camouflage or blur the boundaries of an object, for example, can be seen in architect Douglas Garofalo’s 1991 Camouflage House as well as a vividly hued glass table by Johanna Grawunder (2010). -

Lauretta Vinciarelli

Lauretta Vinciarelli Lauretta Lauretta Vinciarelli Exhibition Checklist Short Wall: Long Wall (left to right): 101 Spring Street March 30–July 20, 2019 I II Public hours: Lauretta Vinciarelli and Leonardo Fodera, [Drawings of the hangar and open and Thursdays, Fridays & Saturdays Puglia project, 1975–1977 enclosed court house], 1980 1:00–5:30pm Ink and colored pencil on mylar Colored pencil on vellum 17 1/4 × 22 3/4 inches (44 × 58 cm) 20 × 32 inches (50.8 × 81.3 cm) Lauretta Vinciarelli is made possible Lauretta Vinciarelli and Leonardo Fodera, [Drawings of the hangar and open and with support from Puglia project, 1975–1977 enclosed court house], 1980 Ronnie Heyman and Loren Pack Ink and colored pencil on mylar Colored pencil on vellum & Robert Beyer 17 1/4 × 42 1/2 inches (44 × 108 cm) 20 × 32 inches (50.8 × 81.3 cm) Lauretta Vinciarelli and Leonardo Fodera, [Drawings of the hangar and open and Puglia project, 1975–1977 enclosed court house], 1980 Ink and colored pencil on mylar Colored pencil on vellum 17 1/4 × 22 3/4 inches (44 × 58 cm) 20 × 32 inches (50.8 × 81.3 cm) Lauretta Vinciarelli and Leonardo Fodera, [Drawings of the hangar and open and Puglia project, 1975–1977 enclosed court house], 1980 Ink and colored pencil on mylar Colored pencil on vellum 17 1/4 × 22 3/4 inches (44 × 58 cm) 20 × 32 inches (50.8 × 81.3 cm) Lauretta Vinciarelli and Leonardo Fodera, Puglia project, 1975–1977 III Ink and colored pencil on mylar 17 1/4 × 22 3/4 inches (44 × 58 cm) [Project for a Productive Garden in an Urban Center in South West Texas], c. -

Theory, Politics, and Feminism at the IAUS in New York Rebecca

AN AMERICAN THINK TANK WITH ‘SOMETHING TOO EUROPEAN ABOUT IT’ Theory, Politics, and Feminism at the IAUS in New York Rebecca Siefert Governors State University, University Park, IL, United States of America Abstract This paper assesses the influence of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) on Peter Eisenman’s Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) in New York City. Founded in 1967, the Institute was a ‘think tank,’ a school, and a site for public discourse, criticized by Italian architectural historian Manfredo Tafuri for having ‘something too European about it.’ Tafuri’s statement serves as a foundation to analyze the IAUS’s complicated relationship to European modernism, by assessing some of the varied projects and groups associated with the Institute. Eisenman’s Conference of Architects for the Study of the Environment (CASE), for example, began in the mid-1960s as a series of meetings on contemporary architectural concerns – in some ways an American counterpart to the earlier CIAM (although Eisenman had actually envisioned CASE as more of a ‘Team 10-like group’). Members of the IAUS were splintered in their positions on architecture’s responsibility to political, social, and aesthetic issues, which prompted the founding of ReVisions, a group formed within the auspices of the IAUS in 1981 that focused on architecture’s thorny relationship to political ideology. This paper addresses the neglected role of ReVisions and women members, topics which have been long neglected in the historiography of the IAUS. A study of the IAUS illustrates the complex influence of CIAM on the direction of architectural intellectualism in New York in the wake of 1968, which is instructive for engaged architects and intellectuals working in the United States today. -

Page 1 of 207

Rendering of Living Room (KA0026_kOSxx2_08_02) Village Scene (KA012201_000009) Sylvia Marlowe Seated at Harpsichord Sign for the David Mannes Music School (MP000601_000001) (MA040101_000085) Rendering of bedroom interior (KA003101_000002) Rendering of Bedroom Interior (KA003101_000004) Print of zinc-plate etching in six panels (KA0087_01) Rendering of Sitting Area (KA003101_OSxx1_f06_04) Rendering of Bedroom for Mrs. Rae in Sewickley, Pennsylvania Rendering of Guest Room for Mrs. Hassler (KA003101_000006) (KA003101_000007) Rendering of Bedroom Interior Rendering of Bedroom Interior (KA003101_000005) (KA003101_000008) Page 1 of 207 Geometric Gouache (KA0027_b01_f06_01) Scandinavian-Inspired Pattern Pink Peony Napkin (KA0027_b01_f14_01) Abstract Batik-Inspired Print (KA0027_b01_f04_01) (KA0027_kOSx3_f02_01) Realist Stereo Slide Viewing Kit (KA0034_b06_f01_01) Opera Performance at Mannes College of Music (MA040101_000058) HOPE YOU HAVE... Carl Bamberger Conducts at Mannes (KA0019_b01_f14_08) College of Music (MA040101_000057) Fashion Show Fashion Show Fashion Show (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_01) (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_02) (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_03) Bonwit Teller Window Display Featuring Linen Dress by Stella Sloat and Vegetable Mask (KA0001_000215) Page 2 of 207 Fashion Show Fashion Show Fashion Show Fashion Show (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_04) (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_05) (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_06) (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_07) Fashion Show Fashion Show Fashion Show Students Observe Man Making a Garment (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_08) (PIC04002_b02_f29_0506_09) -

Architectsnewspaper 3.9.2004

THE ARCHITECTSNEWSPAPER 3.9.2004 NEW YORK ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN WWW.ARCHPAPER.COM $3.95 CITY COLLEGE, AIA-NY, While New York real estate has never had a SO FAR, NEW STATE LAW AIMED AT 00 AND CITY COUNCIL SPONSOR shortage of star architects designing luxury CLAMPING DOWN ON UNLICENSED 04 apartments, middle class and affordable hous• AN IDEAS COMPETITION PROFESSIONALS HAS HAD MINIMAL ALTERNATIVES ing often goes untouched by high-minded LU FOR NEW HOUSING MODELS IMPACT ON ARCHITECTS designers. The recent competition, New —I FOR NETS ARENA Housing New York, aims to address a need o for a dialogue on the very basic component o 08 NEW of residential living in New York. The compe• EMERGING tition, which recently announced its winners, WITHOUT is billed as a "design ideas" competition, VOICES, but has its basis in three real sites in Harlem, CLASS OF 2004 HOUSING Brooklyn's Park Slope Area, and the Queens waterfront. The winning proposals, selected LICENSE 14 from 160 entries from firms small and large, NEW and from as far away as Ohio and Texas, yielded A law was passed last September that prom• RIDING THE some imaginative ideas on what apartments ised to greatly enhance the state's ability to PROUVE WAVE could be like on these separate housing sites. clamp down on unlicensed architects. But YORK Prizes were awarded in first through third now, six months after Governor George E. 16 place for each site. Choi Law/A.V.K.Group Pataki signed the legislation, it remains THE STATEN Andrew Berman's Harlem project of Irving, Texas; Arte continued on page 2 largely a dead letter, with ambiguous lan• guage in the law yet to be clarified and, ISLAND SCENE importantly, with no funding available to put the whole thing into practice.