Queer Geographies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fragile Subjectivities: Constructing Queer Safe Spaces

Social & Cultural Geography ISSN: 1464-9365 (Print) 1470-1197 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rscg20 Fragile subjectivities: constructing queer safe spaces Gilly Hartal To cite this article: Gilly Hartal (2018) Fragile subjectivities: constructing queer safe spaces, Social & Cultural Geography, 19:8, 1053-1072, DOI: 10.1080/14649365.2017.1335877 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1335877 Published online: 08 Jun 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 375 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rscg20 SOCIAL & CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY 2018, VOL. 19, NO. 8, 1053– 1072 https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1335877 Fragile subjectivities: constructing queer safe spaces Gilly Hartal The Department of Geography, McGill University, Montreal, Canada ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This paper uses framing theory to challenge previous understandings Received 22 May 2016 of queer safe space, their construction, and fundamental logics. Safe Accepted 5 May 2017 space is usually apprehended as a protected and inclusive place, where KEYWORDS one can express one’s identity freely and comfortably. Focusing on the Safe space; LGBT space; Jerusalem Open House, a community center for LGBT individuals in queer geographies; LGBT in Jerusalem, I investigate the spatial politics of safe space. Introducing Israel; sexuality and space the contested space of Jerusalem, I analyze five framings of safe space, outlining diverse and oppositional components producing this MOTS CLÉS negotiable construct. The argument is twofold: First, I aim to explicate espace sûr; espace LGBT; five different frames for the creation of safe space. -

Critical Geographical Queer Semiotics

Critical Geographical Queer Semiotics Martin Zebracki School of Geography University of Leeds, UK [email protected] Tommaso M. Milani Department of Linguistics, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg and Department of Swedish, University of Gothenburg [email protected] Critical Geographical Queer Semiotics: Semantics, Syntactics, Pragmatics This Themed Section assembles scholarship on sexual and queer geographies and socio-linguistics to pursue – what we, a collaborating geographer and semiotician, frame as – critical geographical queer semiotics. We regard this as an on-going episteme-techne research frontier at the crossroads of language- focused geographical inquiry (see, e.g., Brown, 2002; Leap and Boellstorff, 2004; Valentine et al., 2008; Browne and Nash, 2010; Murray, 2016) and the unfolding sociolinguistic subdiscipline of linguistic landscaping (see, e.g., Shohamy and Gorter, 2009; Blommaert, 2013; Stroud and Jegels, 2014; Blackwood et al., 2016). At the core of critical geographical queer semiotics are simultaneous knowledge–doings to challenge signs and symbols at the nexus of sexuality, identity and space. This entails a perpetual, unfinished language-driven project, uncovering how text is intrinsically informed by other texts (see intertextuality in Barthes, 1982). Text therefore encompasses a dynamic socio-spatiality interwoven fabric (see Lovejoy, 2004), and can be articulated along multi-scalar, multi- Published with Creative Commons licence: Attribution–Noncommercial–No Derivatives Critical Geographical Queer Semiotics 428 temporal as well as multi-semiotic dimensions of, in this case, everyday sexual citizenship (see Zebracki, 2017). Hence, critical geographical queer semiotics probes into the processes of how discursive systems constitute and deconstruct sexuality-modulated identities of what is known and sensed as ‘place’ (e.g., Scollon and Scollon, 2003). -

Gender and Geography in the United Kingdom, 1980-2006. Documents

DAG 49 001-258 24/2/08 12:05 Página 57 Doc. Anàl. Geogr. 49, 2007 57-72 Gender and geography in the United Kingdom, 1980-2006 Jo Little University of Exeter. Department of Geography Data de recepció: octubre del 2006 Data d’acceptació definitiva: febrer del 2007 Abstract This paper discusses the progress of feminist geography in the UK over the past 25 years. The first part of the paper refers to the earlier books and articles to establish key «moments» in the development of feminist geography in the UK; the second part goes on to docu- ment more recent developments in feminist geography such as the adoption of the con- cept of gender identity; the third section attempts to illustrate the main developments in feminist geography in the UK through reference to my own area of research, rural geography. Finally the paper briefly examines, by way of conclusion, the development of feminist geography in the UK in the context of teaching. Key words: gender, geography, United Kingdom, rural geography, teaching. Resum. Gènere i geografia al Regne Unit, 1980-2006 Aquest article presenta l’evolució de la geografia feminista al Regne Unit en els darrers vint-i-cinc anys. La primera part de l’article es refereix als primers llibres i articles per tal d’es- tablir els «moments» clau en el desenvolupament de la geografia feminista al Regne Unit; la segona part documenta la recerca més recent en geografia feminista, com ara l’adopció del concepte d’identitat de gènere; la tercera secció pretén il·lustrar els principals treballs rea- litzats en relació amb la meva àrea de recerca, la geografia rural. -

1 a Queer Orientation: the Sexual Geographies of Modernism 1913

A Queer Orientation: The Sexual Geographies of Modernism 1913-1939. Sean Richardson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2019 1 Copyright Statement. This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights. 2 Dedication. For Katie, my favourite scream. Acknowledgements. Etymologically, the word ‘thank’ shares its roots with the Indo-European ‘tong-’, to ‘think’ and ‘feel’. When we give thanks today, we may consider the actions or words of others, but I find that tracing this root is generative—it allows me to consider who has helped me think through this thesis, as much as who has helped me feel my way. First, I must thank my supervisors, Andrew Thacker and Catherine Clay. Primarily, of course, my supervisory team has helped me to think: I thank them for pushing me as a reader, a critic and a writer, while giving me the space to work on other projects that have shored me up in myriad ways. And yet Andrew and Cathy have also allowed me to feel—they have given me the space to try, test, write and rewrite. -

Gender and Urban Space

Issue 2013 42 Gender and Urban Space Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

GEOG 507: QUEER GEOGRAPHIES Winter 2017 Wednesdays 2:35-5:25, Burnside 429

GEOG 507: QUEER GEOGRAPHIES Winter 2017 Wednesdays 2:35-5:25, Burnside 429 Prof. Natalie Oswin E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 514-398-5232 Office: Burnside 418 Office hours: Wednesday 10:00-11:00 (or by appointment) Course description: Over the last few decades, geographers have been engaging with queer theory to explore the relationship between sexuality and space. The resulting body of work has greatly expanded our understanding of the spatial productions and expressions of sexual identities. But this important contribution is somewhat paradoxical since queer theory advances a critique of the idea of sexual identity. In this seminar we will go beyond locating ‘queers in space’ to instead advance a ‘queer approach to space’. We will consider the ways in which queer theory can be used in concert with postcolonial, critical race, feminist, and materialist theories. Moving away from a literal sexual referent, we will consider how broad constellations of power involving dynamics of race, gender, class, colonialism, geopolitics, migration, nationalism, and globalization are central to expressions of heternormativity and homonormativity. Though our focus is on developing understanding of queer geographies, the questions we will explore are thoroughly interdisciplinary. As such, the reading list comes from various fields including geography, sociology, cultural studies, law, history and anthropology. Prerequisites: Permission of the instructor. No geography background necessary. This course qualifies as complementary for women’s studies and sexual diversity studies students. Readings: Readings will be made available on myCourses. Evaluation: Requirement Value Date Participation 50% Ongoing Essay proposal 10% March 8 Essay 40% April 5 Participation I expect that you will engage with all course materials and attend all classes. -

King Kong and the Human Fly Meaghan Morris

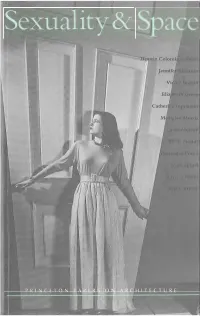

Sexuality & Space Beatriz Colomina, editor Jennifer Bloomer Victor Burgin Elizabeth Grosz Catherine Ingraham Meaghan Morris Laura Mulvey Molly Nesbit Alessandra Ponte Lynn Spigel Patricia White Mark Wigley PRINCETON PAPERS ON ARCHITECTURE Sexuality and Space is the first volume in the series Princeton Papers on Architecture Princeton University School of Architecture Princeton, New Jersey 08544-5264 Editor: Beatriz Colomina Copy Editor: Phil Mariani Designer: Ken Botnick Project Coordinator: Lisa A. Simpson Published by Princeton Architectural Press 37 East 7th Street New York, New York 10003 212.995.9620 © 1992 Princeton Architectural Press All rights reserved 95 94 93 4 3 Printed and bound in Mexico No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sexuality & space I Beatriz Colomina, editor. p. em. -(Princeton papers on architecture: 1) Proceedings of a symposium, held at Princeton University School of Architecture March 10-11, 1990. ISBN 1-878271-o8-3 (paper) : $14.95 1. Space (Art)-Congresses. 2. Space (Architecture)-Congresses. 3. Sexuality in art-Congresses. 4· Arts, Modern-2oth century-Congresses. I. Colomina, Beatriz. II. Title: Sexuality and space. III. Series. NX65o.S8S48 1992 720'. 1-dczo Contents Meaghan Morris I Great Moments in Social Climbing: King Kong and the Human Fly Laura Mulvey 53 Pandora: Topographies of the Mask and Curiosity Beatriz Colomina 73 The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism -

Here, There, Everywhere

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ 1 Here, there, everywhere: 2 the ubiquitous geographies of heteronormativity 3 4 5 Phil Hubbard 6 7 Abstract: From its first tentative forays into questions of gay and 8 lesbian residence, the discipline of geography has made 9 increasingly important contributions to literatures on sexual 10 identities, practices and politics. In this paper, I seek to highlight 11 the breadth and depth of contemporary work on sexuality and 12 space by exploring the contributions made by geographers to the 13 theorization of heteronormativity. Specifically, this paper explores 14 how heterosexual norms are maintained and performed spatially, 15 noting the increasing body of work which moves beyond 16 examination of heterosexuality’s Other (i.e. homosexuality) to 17 consider the multiple desires and bodies that can be 18 accommodated within the category ‘heterosexual’. Moving from 19 urban to rural contexts, this paper hence reviews literatures 20 detailing how particular heterosexual practices are rendered 21 normal, concluding that this literature is usefully shifting from a 22 focus on identity and community to questions of practice and 23 performance. 24 1 1 Introduction 2 3 Long marginalized in the academy, studies of sexuality have now 4 become a familiar – if sometimes contested – fixture in the 5 geographical curriculum. -

The Gendered Body in Virtual Space : Sexuality, Performance and Play in Four Second Life Spaces

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2012 The gendered body in virtual space : sexuality, performance and play in four Second Life spaces Judith Elund Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Elund, J. (2012). The gendered body in virtual space : sexuality, performance and play in four Second Life spaces. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/544 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/544 Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2012 The gendered body in virtual space : sexuality, performance and play in four Second Life spaces Judith Elund Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation Elund, J. (2012). The gendered body in virtual space : sexuality, performance and play in four Second Life spaces. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/544 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/544 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Cities in Film: Architecture, Urban Space and the Moving Image

Cities in Film: Architecture, Urban Space and the Moving Image An International Interdisciplinary Conference University of Liverpool, 26-28th March 2008 Conference Proceedings. This conference is organised by the School of Architecture and School of Politics and Communication Studies. The AHRC-funded research project, entitled City in Film: Liverpool's Urban Landscape and the Moving Image, is conducted by Dr Julia Hallam (principle investigator), Professor Robert Kronenburg (co-investigator), Dr Richard Koeck and Dr Les Roberts. This conference is supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the University of Liverpool. Cover design: Richard Koeck and Les Roberts. Copyright cover image: Angus Tilston. Edited by Julia Hallam, Robert Kronenburg, Richard Koeck and Les Roberts. Please note that authors are responsible for copyright clearance of images reproduced in the proceedings. Cities in Film: Architecture, Urban Space and the Moving Image An International Interdisciplinary Conference University of Liverpool, 26-28th March 2008 Cities in Film explores the relationship between film, architecture and the urban landscape drawing on interests in film, architecture, urban studies and civic design, cultural geography, cultural studies and related fields. The conference is part of University of Liverpool's contribution to the European Capital of Culture 2008, and aims to foster interdisciplinary dialogues around architectural and film history and theory, film and urban space, and to point towards new intellectual frameworks for discussion. It seeks to draw on the work of theorists and practitioners engaged in ideas in these areas, examining film in the context of urban design and development and exploring in particular the contested social, cultural and political terrain that underpins these practices. -

The Space and Place of Sexuality: How Rural Lesbians and Gays Narrate Identity

The Space and Place of Sexuality: How Rural Lesbians and Gays Narrate Identity by Emily A. Kazyak A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Karin A. Martin, Chair Professor Margaret R. Somers Professor Alford A. Young, Jr. Associate Professor Nadine M. Hubbs Assistant Professor Gayle S. Rubin To my family ii Acknowledgements I am grateful for the many people in my life whose support made it possible for me to write this story. First and foremost, I could not have completed this dissertation or graduate school without the love and encouragement my family continually provides. This project would not have taken the shape it has without my wife, Jaime Brunton. Your willingness to engage in numerous conversations about the questions and issues I grapple with in my dissertation has enriched my thinking and this manuscript. Thank you for helping me celebrate the achievements and calming me through the transitions. I’m looking forward to our adventures in Nebraska! May the prairie hold good things for our family. My parents, Don and Lucy Kazyak, have done a beautiful job of recognizing my academic accomplishments alongside other important moments that have occurred in my life over the past six years. That balance has given me the ability to stay grounded, connected to my roots, and humble through this process. Thank you both for your unconditional love. I am equally grateful for the support from my brother and sister in- law, Brian Kazyak and Shannon Preston-Kazyak, and my sister and brother in-law, Alison and Jeff Weinschenk. -

CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS with Post-Print Updates

EUROPEAN GEOGRAPHIES OF SEXUALITIES CONFERENCE PRAGUE / SEPTEMBER 26th-28th 2019 CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS with post-print updates ueerGeography Title: V. European Geographies of Sexualities Conference proceedings Edited by: Michal Pitoňák, Lukáš Pitoňák Publisher: Queer Geography, z. s. Márova 2806/10 Prague 5 155 00 Prague, Czechia Publication date: 30. 8. 2019 ISBN 978-80-88271-04-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS ORGANIZATION . 4 ABOUT THE CONFERENCE . 5 VENUE MAP . 6 HOW TO READ YOUR CONFERENCE BADGE . 8 THE GENERAL CONFERENCE CALL FOR ABSTRACTS . 9 INVITED SPEAKERS AND THEIR KEYNOTE ADDRESSES . 12 THE BOOK OF ABSTRACTS . 19 INDEPENDENTLY ORGANIZED SESSIONS . 20 SESSIONS BASED ON SUBMISSIONS FROM THE GENERAL CALL . 74 SIDE EVENTS . 107 LIST OF COUNTRIES BASED ON CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS:. 110 LIST OF NAMES . 111 DETAILED CONFERENCE PROGRAM . 114 CONDENSED PROGRAM . 128 NOTES . 132 3 ORGANIZATION Conference organizers: • Queer Geography, z. s. (main organizer) www.queergeography.cz • Charles University, Faculty of Science, Department of Social Geography and Regional Development (host institution) www.natur.cuni.cz • Czech Geographical Society (host organization) www.geography.cz/ General partners: Supporters: • Space Sexualities and Queer Research Group • Primeros Prague a.s. (SSQRG) of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) with the Institute of British Geographers (IBG) • Gilead Sciences s.r.o. supported this event in the form of donation grant Conference dates: 26-28th September, 2019 Website: 2019.egsconference.com Conference venue: Charles University,