On the Works of Euler and His Followers on Spherical Geometry Athanase Papadopoulos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proofs with Perpendicular Lines

3.4 Proofs with Perpendicular Lines EEssentialssential QQuestionuestion What conjectures can you make about perpendicular lines? Writing Conjectures Work with a partner. Fold a piece of paper D in half twice. Label points on the two creases, as shown. a. Write a conjecture about AB— and CD — . Justify your conjecture. b. Write a conjecture about AO— and OB — . AOB Justify your conjecture. C Exploring a Segment Bisector Work with a partner. Fold and crease a piece A of paper, as shown. Label the ends of the crease as A and B. a. Fold the paper again so that point A coincides with point B. Crease the paper on that fold. b. Unfold the paper and examine the four angles formed by the two creases. What can you conclude about the four angles? B Writing a Conjecture CONSTRUCTING Work with a partner. VIABLE a. Draw AB — , as shown. A ARGUMENTS b. Draw an arc with center A on each To be prof cient in math, side of AB — . Using the same compass you need to make setting, draw an arc with center B conjectures and build a on each side of AB— . Label the C O D logical progression of intersections of the arcs C and D. statements to explore the c. Draw CD — . Label its intersection truth of your conjectures. — with AB as O. Write a conjecture B about the resulting diagram. Justify your conjecture. CCommunicateommunicate YourYour AnswerAnswer 4. What conjectures can you make about perpendicular lines? 5. In Exploration 3, f nd AO and OB when AB = 4 units. -

Examples of Manifolds

Examples of Manifolds Example 1 (Open Subset of IRn) Any open subset, O, of IRn is a manifold of dimension n. One possible atlas is A = (O, ϕid) , where ϕid is the identity map. That is, ϕid(x) = x. n Of course one possible choice of O is IR itself. Example 2 (The Circle) The circle S1 = (x,y) ∈ IR2 x2 + y2 = 1 is a manifold of dimension one. One possible atlas is A = {(U , ϕ ), (U , ϕ )} where 1 1 1 2 1 y U1 = S \{(−1, 0)} ϕ1(x,y) = arctan x with − π < ϕ1(x,y) <π ϕ1 1 y U2 = S \{(1, 0)} ϕ2(x,y) = arctan x with 0 < ϕ2(x,y) < 2π U1 n n n+1 2 2 Example 3 (S ) The n–sphere S = x =(x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ IR x1 +···+xn+1 =1 n A U , ϕ , V ,ψ i n is a manifold of dimension . One possible atlas is 1 = ( i i) ( i i) 1 ≤ ≤ +1 where, for each 1 ≤ i ≤ n + 1, n Ui = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi > 0 ϕi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n Vi = (x1, ··· ,xn+1) ∈ S xi < 0 ψi(x1, ··· ,xn+1)=(x1, ··· ,xi−1,xi+1, ··· ,xn+1) n So both ϕi and ψi project onto IR , viewed as the hyperplane xi = 0. Another possible atlas is n n A2 = S \{(0, ··· , 0, 1)}, ϕ , S \{(0, ··· , 0, −1)},ψ where 2x1 2xn ϕ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1−xn+1 1−xn+1 2x1 2xn ψ(x , ··· ,xn ) = , ··· , 1 +1 1+xn+1 1+xn+1 are the stereographic projections from the north and south poles, respectively. -

An Introduction to Topology the Classification Theorem for Surfaces by E

An Introduction to Topology An Introduction to Topology The Classification theorem for Surfaces By E. C. Zeeman Introduction. The classification theorem is a beautiful example of geometric topology. Although it was discovered in the last century*, yet it manages to convey the spirit of present day research. The proof that we give here is elementary, and its is hoped more intuitive than that found in most textbooks, but in none the less rigorous. It is designed for readers who have never done any topology before. It is the sort of mathematics that could be taught in schools both to foster geometric intuition, and to counteract the present day alarming tendency to drop geometry. It is profound, and yet preserves a sense of fun. In Appendix 1 we explain how a deeper result can be proved if one has available the more sophisticated tools of analytic topology and algebraic topology. Examples. Before starting the theorem let us look at a few examples of surfaces. In any branch of mathematics it is always a good thing to start with examples, because they are the source of our intuition. All the following pictures are of surfaces in 3-dimensions. In example 1 by the word “sphere” we mean just the surface of the sphere, and not the inside. In fact in all the examples we mean just the surface and not the solid inside. 1. Sphere. 2. Torus (or inner tube). 3. Knotted torus. 4. Sphere with knotted torus bored through it. * Zeeman wrote this article in the mid-twentieth century. 1 An Introduction to Topology 5. -

The Sphere Project

;OL :WOLYL 7YVQLJ[ +XPDQLWDULDQ&KDUWHUDQG0LQLPXP 6WDQGDUGVLQ+XPDQLWDULDQ5HVSRQVH ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[ 7KHULJKWWROLIHZLWKGLJQLW\ ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[PZHUPUP[PH[P]L[VKL[LYTPULHUK WYVTV[LZ[HUKHYKZI`^OPJO[OLNSVIHSJVTT\UP[` /\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY YLZWVUKZ[V[OLWSPNO[VMWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ /\THUP[HYPHU >P[O[OPZ/HUKIVVR:WOLYLPZ^VYRPUNMVYH^VYSKPU^OPJO [OLYPNO[VMHSSWLVWSLHMMLJ[LKI`KPZHZ[LYZ[VYLLZ[HISPZO[OLPY *OHY[LYHUK SP]LZHUKSP]LSPOVVKZPZYLJVNUPZLKHUKHJ[LK\WVUPU^H`Z[OH[ YLZWLJ[[OLPY]VPJLHUKWYVTV[L[OLPYKPNUP[`HUKZLJ\YP[` 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZ This Handbook contains: PU/\THUP[HYPHU (/\THUP[HYPHU*OHY[LY!SLNHSHUKTVYHSWYPUJPWSLZ^OPJO HUK YLÅLJ[[OLYPNO[ZVMKPZHZ[LYHMMLJ[LKWVW\SH[PVUZ 4PUPT\T:[HUKHYKZPU/\THUP[HYPHU9LZWVUZL 9LZWVUZL 7YV[LJ[PVU7YPUJPWSLZ *VYL:[HUKHYKZHUKTPUPT\TZ[HUKHYKZPUMV\YRL`SPMLZH]PUN O\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYZ!>H[LYZ\WWS`ZHUP[H[PVUHUKO`NPLUL WYVTV[PVU"-VVKZLJ\YP[`HUKU\[YP[PVU":OLS[LYZL[[SLTLU[HUK UVUMVVKP[LTZ"/LHS[OHJ[PVU;OL`KLZJYPILwhat needs to be achieved in a humanitarian response in order for disaster- affected populations to survive and recover in stable conditions and with dignity. ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVRLUQV`ZIYVHKV^ULYZOPWI`HNLUJPLZHUK PUKP]PK\HSZVMMLYPUN[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VYH common language for working together towards quality and accountability in disaster and conflict situations ;OL:WOLYL/HUKIVVROHZHU\TILYVMºJVTWHUPVU Z[HUKHYKZ»L_[LUKPUNP[ZZJVWLPUYLZWVUZL[VULLKZ[OH[ OH]LLTLYNLK^P[OPU[OLO\THUP[HYPHUZLJ[VY ;OL:WOLYL7YVQLJ[^HZPUP[PH[LKPU I`HU\TILY VMO\THUP[HYPHU5.6ZHUK[OL9LK*YVZZHUK 9LK*YLZJLU[4V]LTLU[ ,+0;065 7KHB6SKHUHB3URMHFWBFRYHUBHQBLQGG The Sphere Project Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response Published by: The Sphere Project Copyright@The Sphere Project 2011 Email: [email protected] Website : www.sphereproject.org The Sphere Project was initiated in 1997 by a group of NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement to develop a set of universal minimum standards in core areas of humanitarian response: the Sphere Handbook. -

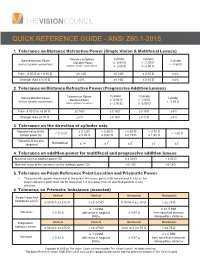

Quick Reference Guide - Ansi Z80.1-2015

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE - ANSI Z80.1-2015 1. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Single Vision & Multifocal Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -4.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -4.50 D From - 6.50 D to + 6.50 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% Stronger than ± 6.50 D ± 2% ± 0.13 D ± 0.15 D ± 4% 2. Tolerance on Distance Refractive Power (Progressive Addition Lenses) Cylinder Cylinder Sphere Meridian Power Tolerance on Sphere Cylinder Meridian Power ≥ 0.00 D > - 2.00 D (minus cylinder convention) > -3.50 D (minus cylinder convention) ≤ -2.00 D ≤ -3.50 D From -8.00 D to +8.00 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% Stronger than ±8.00 D ± 2% ± 0.16 D ± 0.18 D ± 5% 3. Tolerance on the direction of cylinder axis Nominal value of the ≥ 0.12 D > 0.25 D > 0.50 D > 0.75 D < 0.12 D > 1.50 D cylinder power (D) ≤ 0.25 D ≤ 0.50 D ≤ 0.75 D ≤ 1.50 D Tolerance of the axis Not Defined ° ° ° ° ° (degrees) ± 14 ± 7 ± 5 ± 3 ± 2 4. Tolerance on addition power for multifocal and progressive addition lenses Nominal value of addition power (D) ≤ 4.00 D > 4.00 D Nominal value of the tolerance on the addition power (D) ± 0.12 D ± 0.18 D 5. Tolerance on Prism Reference Point Location and Prismatic Power • The prismatic power measured at the prism reference point shall not exceed 0.33Δ or the prism reference point shall not be more than 1.0 mm away from its specified position in any direction. -

1 Chapter 3 Plane and Spherical Trigonometry 3.1

1 CHAPTER 3 PLANE AND SPHERICAL TRIGONOMETRY 3.1 Introduction It is assumed in this chapter that readers are familiar with the usual elementary formulas encountered in introductory trigonometry. We start the chapter with a brief review of the solution of a plane triangle. While most of this will be familiar to readers, it is suggested that it be not skipped over entirely, because the examples in it contain some cautionary notes concerning hidden pitfalls. This is followed by a quick review of spherical coordinates and direction cosines in three- dimensional geometry. The formulas for the velocity and acceleration components in two- dimensional polar coordinates and three-dimensional spherical coordinates are developed in section 3.4. Section 3.5 deals with the trigonometric formulas for solving spherical triangles. This is a fairly long section, and it will be essential reading for those who are contemplating making a start on celestial mechanics. Sections 3.6 and 3.7 deal with the rotation of axes in two and three dimensions, including Eulerian angles and the rotation matrix of direction cosines. Finally, in section 3.8, a number of commonly encountered trigonometric formulas are gathered for reference. 3.2 Plane Triangles . This section is to serve as a brief reminder of how to solve a plane triangle. While there may be a temptation to pass rapidly over this section, it does contain a warning that will become even more pertinent in the section on spherical triangles. Conventionally, a plane triangle is described by its three angles A, B, C and three sides a, b, c, with a being opposite to A, b opposite to B, and c opposite to C. -

Using Non-Euclidean Geometry to Teach Euclidean Geometry to K–12 Teachers

Using non-Euclidean Geometry to teach Euclidean Geometry to K–12 teachers David Damcke Department of Mathematics, University of Portland, Portland, OR 97203 [email protected] Tevian Dray Department of Mathematics, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 [email protected] Maria Fung Mathematics Department, Western Oregon University, Monmouth, OR 97361 [email protected] Dianne Hart Department of Mathematics, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 [email protected] Lyn Riverstone Department of Mathematics, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 [email protected] January 22, 2008 Abstract The Oregon Mathematics Leadership Institute (OMLI) is an NSF-funded partner- ship aimed at increasing mathematics achievement of students in partner K–12 schools through the creation of sustainable leadership capacity. OMLI’s 3-week summer in- stitute offers content and leadership courses for in-service teachers. We report here on one of the content courses, entitled Comparing Different Geometries, which en- hances teachers’ understanding of the (Euclidean) geometry in the K–12 curriculum by studying two non-Euclidean geometries: taxicab geometry and spherical geometry. By confronting teachers from mixed grade levels with unfamiliar material, while mod- eling protocol-based pedagogy intended to emphasize a cooperative, risk-free learning environment, teachers gain both content knowledge and insight into the teaching of mathematical thinking. Keywords: Cooperative groups, Euclidean geometry, K–12 teachers, Norms and protocols, Rich mathematical tasks, Spherical geometry, Taxicab geometry 1 1 Introduction The Oregon Mathematics Leadership Institute (OMLI) is a Mathematics/Science Partner- ship aimed at increasing mathematics achievement of K–12 students by providing professional development opportunities for in-service teachers. -

And Are Lines on Sphere B That Contain Point Q

11-5 Spherical Geometry Name each of the following on sphere B. 3. a triangle SOLUTION: are examples of triangles on sphere B. 1. two lines containing point Q SOLUTION: and are lines on sphere B that contain point Q. ANSWER: 4. two segments on the same great circle SOLUTION: are segments on the same great circle. ANSWER: and 2. a segment containing point L SOLUTION: is a segment on sphere B that contains point L. ANSWER: SPORTS Determine whether figure X on each of the spheres shown is a line in spherical geometry. 5. Refer to the image on Page 829. SOLUTION: Notice that figure X does not go through the pole of ANSWER: the sphere. Therefore, figure X is not a great circle and so not a line in spherical geometry. ANSWER: no eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 11-5 Spherical Geometry 6. Refer to the image on Page 829. 8. Perpendicular lines intersect at one point. SOLUTION: SOLUTION: Notice that the figure X passes through the center of Perpendicular great circles intersect at two points. the ball and is a great circle, so it is a line in spherical geometry. ANSWER: yes ANSWER: PERSEVERANC Determine whether the Perpendicular great circles intersect at two points. following postulate or property of plane Euclidean geometry has a corresponding Name two lines containing point M, a segment statement in spherical geometry. If so, write the containing point S, and a triangle in each of the corresponding statement. If not, explain your following spheres. reasoning. 7. The points on any line or line segment can be put into one-to-one correspondence with real numbers. -

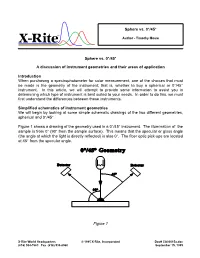

Sphere Vs. 0°/45° a Discussion of Instrument Geometries And

Sphere vs. 0°/45° ® Author - Timothy Mouw Sphere vs. 0°/45° A discussion of instrument geometries and their areas of application Introduction When purchasing a spectrophotometer for color measurement, one of the choices that must be made is the geometry of the instrument; that is, whether to buy a spherical or 0°/45° instrument. In this article, we will attempt to provide some information to assist you in determining which type of instrument is best suited to your needs. In order to do this, we must first understand the differences between these instruments. Simplified schematics of instrument geometries We will begin by looking at some simple schematic drawings of the two different geometries, spherical and 0°/45°. Figure 1 shows a drawing of the geometry used in a 0°/45° instrument. The illumination of the sample is from 0° (90° from the sample surface). This means that the specular or gloss angle (the angle at which the light is directly reflected) is also 0°. The fiber optic pick-ups are located at 45° from the specular angle. Figure 1 X-Rite World Headquarters © 1995 X-Rite, Incorporated Doc# CA00015a.doc (616) 534-7663 Fax (616) 534-8960 September 15, 1995 Figure 2 shows a drawing of the geometry used in an 8° diffuse sphere instrument. The sphere wall is lined with a highly reflective white substance and the light source is located on the rear of the sphere wall. A baffle prevents the light source from directly illuminating the sample, thus providing diffuse illumination. The sample is viewed at 8° from perpendicular which means that the specular or gloss angle is also 8° from perpendicular. -

A Comet of the Enlightenment Anders Johan Lexell's Life and Discoveries Series: Vita Mathematica

birkhauser-science.de Johan C.-E. Stén A Comet of the Enlightenment Anders Johan Lexell's Life and Discoveries Series: Vita Mathematica The first-ever full-length biography of the mathematician and astronomer Anders Johan Lexell (1740–1784) Sheds new light on the collaborators of Leonhard Euler Interesting study of a scientist's grand tour through enlightened Europe The Finnish mathematician and astronomer Anders Johan Lexell (1740–1784) was a long-time close collaborator as well as the academic successor of Leonhard Euler at the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg. Lexell was initially invited by Euler from his native town of Abo (Turku) in Finland to Saint Petersburg to assist in the mathematical processing of the astronomical data of the forthcoming transit of Venus of 1769. A few years later he 2014, XVI, 300 p. 46 illus., 16 illus. in became an ordinary member of the Academy. This is the first-ever full-length biography color. devoted to Lexell and his prolific scientific output. His rich correspondence especially from his grand tour to Germany, France and England reveals him as a lucid observer of the intellectual Printed book landscape of enlightened Europe. In the skies, a comet, a minor planet and a crater on the Hardcover Moon named after Lexell also perpetuate his memory. 129,99 € | £109.99 | $159.99 [1]139,09 € (D) | 142,99 € (A) | CHF 153,50 Softcover 89,99 € | £79.99 | $109.99 [1]96,29 € (D) | 98,99 € (A) | CHF 106,50 eBook 74,89 € | £63.99 | $84.99 [2]74,89 € (D) | 74,89 € (A) | CHF 85,00 Available from your library or springer.com/shop MyCopy [3] Printed eBook for just € | $ 24.99 springer.com/mycopy Order online at springer.com / or for the Americas call (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER / or email us at: [email protected]. -

Geometry: Euclid and Beyond, by Robin Hartshorne, Springer-Verlag, New York, 2000, Xi+526 Pp., $49.95, ISBN 0-387-98650-2

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 39, Number 4, Pages 563{571 S 0273-0979(02)00949-7 Article electronically published on July 9, 2002 Geometry: Euclid and beyond, by Robin Hartshorne, Springer-Verlag, New York, 2000, xi+526 pp., $49.95, ISBN 0-387-98650-2 1. Introduction The first geometers were men and women who reflected on their experiences while doing such activities as building small shelters and bridges, making pots, weaving cloth, building altars, designing decorations, or gazing into the heavens for portentous signs or navigational aides. Main aspects of geometry emerged from three strands of early human activity that seem to have occurred in most cultures: art/patterns, navigation/stargazing, and building structures. These strands developed more or less independently into varying studies and practices that eventually were woven into what we now call geometry. Art/Patterns: To produce decorations for their weaving, pottery, and other objects, early artists experimented with symmetries and repeating patterns. Later the study of symmetries of patterns led to tilings, group theory, crystallography, finite geometries, and in modern times to security codes and digital picture com- pactifications. Early artists also explored various methods of representing existing objects and living things. These explorations led to the study of perspective and then projective geometry and descriptive geometry, and (in the 20th century) to computer-aided graphics, the study of computer vision in robotics, and computer- generated movies (for example, Toy Story ). Navigation/Stargazing: For astrological, religious, agricultural, and other purposes, ancient humans attempted to understand the movement of heavenly bod- ies (stars, planets, Sun, and Moon) in the apparently hemispherical sky. -

Spherical Trigonometry

Spherical trigonometry 1 The spherical Pythagorean theorem Proposition 1.1 On a sphere of radius R, any right triangle 4ABC with \C being the right angle satisfies cos(c=R) = cos(a=R) cos(b=R): (1) Proof: Let O be the center of the sphere, we may assume its coordinates are (0; 0; 0). We may rotate −! the sphere so that A has coordinates OA = (R; 0; 0) and C lies in the xy-plane, see Figure 1. Rotating z B y O(0; 0; 0) C A(R; 0; 0) x Figure 1: The Pythagorean theorem for a spherical right triangle around the z axis by β := AOC takes A into C. The edge OA moves in the xy-plane, by β, thus −−!\ the coordinates of C are OC = (R cos(β);R sin(β); 0). Since we have a right angle at C, the plane of 4OBC is perpendicular to the plane of 4OAC and it contains the z axis. An orthonormal basis −−! −! of the plane of 4OBC is given by 1=R · OC = (cos(β); sin(β); 0) and the vector OZ := (0; 0; 1). A rotation around O in this plane by α := \BOC takes C into B: −−! −−! −! OB = cos(α) · OC + sin(α) · R · OZ = (R cos(β) cos(α);R sin(β) cos(α);R sin(α)): Introducing γ := \AOB, we have −! −−! OA · OB R2 cos(α) cos(β) cos(γ) = = : R2 R2 The statement now follows from α = a=R, β = b=R and γ = c=R. ♦ To prove the rest of the formulas of spherical trigonometry, we need to show the following.