High Level Language Programs Versus Machine Code You All Have Experience Programming in a High Level Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • The central theme of this book is to learn how to solve problems by writing a program . • This book teaches you how to create programs by using the Java programming languages . • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers , desktop computers , and small hand-held devices . 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Computer programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Bus Storage Communication Input Output Memory CPU Devices Devices Devices Devices e.g., Disk, CD, e.g., Modem, e.g., Keyboard, e.g., Monitor, and Tape and NIC Mouse Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. CMPS161 Class Notes (Chap 01) Page 1 / 15 Kuo-pao Yang 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. -

Language Translators

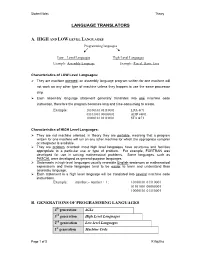

Student Notes Theory LANGUAGE TRANSLATORS A. HIGH AND LOW LEVEL LANGUAGES Programming languages Low – Level Languages High-Level Languages Example: Assembly Language Example: Pascal, Basic, Java Characteristics of LOW Level Languages: They are machine oriented : an assembly language program written for one machine will not work on any other type of machine unless they happen to use the same processor chip. Each assembly language statement generally translates into one machine code instruction, therefore the program becomes long and time-consuming to create. Example: 10100101 01110001 LDA &71 01101001 00000001 ADD #&01 10000101 01110001 STA &71 Characteristics of HIGH Level Languages: They are not machine oriented: in theory they are portable , meaning that a program written for one machine will run on any other machine for which the appropriate compiler or interpreter is available. They are problem oriented: most high level languages have structures and facilities appropriate to a particular use or type of problem. For example, FORTRAN was developed for use in solving mathematical problems. Some languages, such as PASCAL were developed as general-purpose languages. Statements in high-level languages usually resemble English sentences or mathematical expressions and these languages tend to be easier to learn and understand than assembly language. Each statement in a high level language will be translated into several machine code instructions. Example: number:= number + 1; 10100101 01110001 01101001 00000001 10000101 01110001 B. GENERATIONS OF PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES 4th generation 4GLs 3rd generation High Level Languages 2nd generation Low-level Languages 1st generation Machine Code Page 1 of 5 K Aquilina Student Notes Theory 1. MACHINE LANGUAGE – 1ST GENERATION In the early days of computer programming all programs had to be written in machine code. -

Complete Code Generation from UML State Machine

Complete Code Generation from UML State Machine Van Cam Pham, Ansgar Radermacher, Sebastien´ Gerard´ and Shuai Li CEA, LIST, Laboratory of Model Driven Engineering for Embedded Systems, P.C. 174, Gif-sur-Yvette, 91191, France Keywords: UML State Machine, Code Generation, Semantics-conformance, Efficiency, Events, C++. Abstract: An event-driven architecture is a useful way to design and implement complex systems. The UML State Machine and its visualizations are a powerful means to the modeling of the logical behavior of such an archi- tecture. In Model Driven Engineering, executable code can be automatically generated from state machines. However, existing generation approaches and tools from UML State Machines are still limited to simple cases, especially when considering concurrency and pseudo states such as history, junction, and event types. This paper provides a pattern and tool for complete and efficient code generation approach from UML State Ma- chine. It extends IF-ELSE-SWITCH constructions of programming languages with concurrency support. The code generated with our approach has been executed with a set of state-machine examples that are part of a test-suite described in the recent OMG standard Precise Semantics Of State Machine. The traced execution results comply with the standard and are a good hint that the execution is semantically correct. The generated code is also efficient: it supports multi-thread-based concurrency, and the (static and dynamic) efficiency of generated code is improved compared to considered approaches. 1 INTRODUCTION Completeness: Existing tools and approaches mainly focus on the sequential aspect while the concurrency The UML State Machine (USM) (Specification and of state machines is limitedly supported. -

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java

Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, Programs, and Java 1.1 Introduction • Java is the Internet program language • Why Java? The answer is that Java enables user to deploy applications on the Internet for servers, desktop computers, and small hand-held devices. 1.2 What is a Computer? • A computer is an electronic device that stores and processes data. • A computer includes both hardware and software. o Hardware is the physical aspect of the computer that can be seen. o Software is the invisible instructions that control the hardware and make it work. • Programming consists of writing instructions for computers to perform. • A computer consists of the following hardware components o CPU (Central Processing Unit) o Memory (Main memory) o Storage Devices (hard disk, floppy disk, CDs) o Input/Output devices (monitor, printer, keyboard, mouse) o Communication devices (Modem, NIC (Network Interface Card)). Memory Disk, CD, and Storage Input Keyboard, Tape Devices Devices Mouse CPU Modem, and Communication Output Monitor, NIC Devices Devices Printer FIGURE 1.1 A computer consists of a CPU, memory, Hard disk, floppy disk, monitor, printer, and communication devices. 1.2.1 Central Processing Unit (CPU) • The central processing unit (CPU) is the brain of a computer. • It retrieves instructions from memory and executes them. • The CPU usually has two components: a control Unit and Arithmetic/Logic Unit. • The control unit coordinates the actions of the other components. • The ALU unit performs numeric operations (+ - / *) and logical operations (comparison). • The CPU speed is measured by clock speed in megahertz (MHz), with 1 megahertz equaling 1 million pulses per second. -

What Is a Computer Program? 1 High-Level Vs Low-Level Languages

What Is A Computer Program? Scientific Computing Fall, 2019 Paul Gribble 1 High-level vs low-level languages1 2 Interpreted vs compiled languages3 What is a computer program? What is code? What is a computer language? A computer program is simply a series of instructions that the computer executes, one after the other. An instruction is a single command. A program is a series of instructions. Code is another way of referring to a single instruction or a series of instructions (a program). 1 High-level vs low-level languages The CPU (central processing unit) chip(s) that sit on the motherboard of your computer is the piece of hardware that actually executes instructions. A CPU only understands a relatively low-level language called machine code. Often machine code is generated automatically by translating code written in assembly language, which is a low-level programming language that has a relatively direcy relationship to machine code (but is more readable by a human). A utility program called an assembler is what translates assembly language code into machine code. In this course we will be learning how to program in MATLAB, which is a high-level programming language. The “high-level” refers to the fact that the language has a strong abstraction from the details of the computer (the details of the machine code). A “strong abstraction” means that one can operate using high-level instructions without having to worry about the low-level details of carrying out those instructions. An analogy is motor skill learning. A high-level language for human action might be drive your car to the grocery store and buy apples. -

Chapter 1 Basic Principles of Programming Languages

Chapter 1 Basic Principles of Programming Languages Although there exist many programming languages, the differences among them are insignificant compared to the differences among natural languages. In this chapter, we discuss the common aspects shared among different programming languages. These aspects include: programming paradigms that define how computation is expressed; the main features of programming languages and their impact on the performance of programs written in the languages; a brief review of the history and development of programming languages; the lexical, syntactic, and semantic structures of programming languages, data and data types, program processing and preprocessing, and the life cycles of program development. At the end of the chapter, you should have learned: what programming paradigms are; an overview of different programming languages and the background knowledge of these languages; the structures of programming languages and how programming languages are defined at the syntactic level; data types, strong versus weak checking; the relationship between language features and their performances; the processing and preprocessing of programming languages, compilation versus interpretation, and different execution models of macros, procedures, and inline procedures; the steps used for program development: requirement, specification, design, implementation, testing, and the correctness proof of programs. The chapter is organized as follows. Section 1.1 introduces the programming paradigms, performance, features, and the development of programming languages. Section 1.2 outlines the structures and design issues of programming languages. Section 1.3 discusses the typing systems, including types of variables, type equivalence, type conversion, and type checking during the compilation. Section 1.4 presents the preprocessing and processing of programming languages, including macro processing, interpretation, and compilation. -

User's Guide and Reference

IBM Compiler and Library for REXX on IBM Z Version 1 Release 4 User’s Guide and Reference IBM SH19-8160-06 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, be sure to read the general information under Appendix G, “Notices,” on page 267. Seventh Edition, August 2013 This edition applies to version 1 release 4 of IBM Compiler for REXX on IBM Z (product number 5695-013) and the IBM Library for REXX on IBM Z (product number 5695-014), and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. This edition replaces SH19-8160-04. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 1991, 2013. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About This Book..................................................................................................xix How to Read the Syntax Notation............................................................................................................. xix How This Book Is Organized..................................................................................................................... xix How to Send Your Comments.................................................................................................................... xx What's New in Release 4..................................................................................... xxi IBM Compiler for REXX on IBM Z..............................................................................................................xxi -

Virtual Machines for Dynamic Languages Ausgewählte Kapitel Der Systemsoftwaretechnik, WS2021

Virtual Machines for Dynamic Languages Ausgewählte Kapitel der Systemsoftwaretechnik, WS2021 Mark Deutel Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU) Erlangen, Germany [email protected] ABSTRACT threading model. It is common that once a dynamic language has A common approach to execute dynamic languages is inside a vir- grown popular enough the interpreter is extended by a just-in-time tual machine (VM), usually implemented in a low level system (JIT) compiler to more efficiently execute interpreted code. language like C. Such VMs have to support the often complex However this approach does not come without problems. The syntax and semantics of the dynamic languages they are hosting. effort required to write a complete virtual machine from scratch Additionally, some properties of dynamic language code can only is huge. It also forces the language implementer to deal with plat- be inferred at runtime making the optimization of code execution form or target architecture specific details. This makes implement- another challenging task. Therefore, it is hardly possible to provide ing a VM time consuming, error prone, and complicated to port general purpose implementations that support a large range of to other systems. Additionally, modern dynamic languages like different dynamic languages. Furthermore, many commonly used Python, Ruby or JavaScript evolve rapidly and have complex syn- dynamic languages such as Python or Javascript are still evolving tax and semantics. This not only makes it hard to represent the which means that their VMs have to adapt constantly. This implies language properly in low level code, but makes maintenance of that it is necessary to write and maintain a sufficiently elaborated existing VM implementations a complicated task as well. -

SDL - the Iot Language Edel Sherratt, Ileana Ober, Emmanuel Gaudin, Pau Fonseca I Casas, Finn Kristoffersen

SDL - the IoT Language Edel Sherratt, Ileana Ober, Emmanuel Gaudin, Pau Fonseca I Casas, Finn Kristoffersen To cite this version: Edel Sherratt, Ileana Ober, Emmanuel Gaudin, Pau Fonseca I Casas, Finn Kristoffersen. SDL - the IoT Language. 17th International System Design Languages Forum (SDL 2015), Oct 2015, Berlin, Germany. pp. 27-41. hal-01332271 HAL Id: hal-01332271 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01332271 Submitted on 15 Jun 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Open Archive TOULOUSE Archive Ouverte ( OATAO ) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where po ssible. This is an author-deposited version published in : http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/ Eprints ID : 15419 The contribution was presented at SDL 2015 : http://sdl-forum.org/Events/ To cite this version : Sherratt, Edel and Ober, Ileana and Gaudin, Emmanuel and Fonseca I Casas, Pau and Kristoffersen, Finn SDL - the IoT Language. (2015) In: 17th International System Design Languages Forum (SDL 2015), 12 October 2015 - 14 October 2015 (Berlin, Germany). Any corresponde nce concerning this service should be sent to the repository administrator: staff -oatao@listes -diff.inp -toulouse.fr SDL - the IoT Language Edel Sherratt 1, Ileana Ober 2, Emmanuel Gaudin 3, Pau Fonseca i Casas 4, and Finn Kristoffersen 5 1 Aberystwyth University 2 IRIT, Universit´ePaul Sabatier 3 PragmaDev SARL 4 Universitat Polit`ecnica de Catalunya 5 Cinderella ApS Abstract. -

Bug Finding Methods for Multithreaded Student Programming Projects

Bug Finding Methods for Multithreaded Student Programming Projects William Naciri Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science and Applications Godmar V. Back, Chair Ali R. Butt Dongyoon Lee June 23, 2017 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Binary Instrumentation, Multithreaded Programming, Debugging Copyright 2017, William Naciri Bug Finding Methods for Multithreaded Student Programming Projects William Naciri (ABSTRACT) The fork-join framework project is one of the more challenging programming assignments in the computer science curriculum at Virginia Tech. Students in Computer Systems must manage a pool of threads to facilitate the shared execution of dynamically created tasks. This project is difficult because students must overcome the challenges of concurrent programming and conform to the project's specific semantic requirements. When working on the project, many students received inconsistent test results and were left confused when debugging. The suggested debugging tool, Helgrind, is a general-purpose thread error detector. It is limited in its ability to help fix bugs because it lacks knowledge of the specific semantic requirements of the fork-join framework. Thus, there is a need for a special-purpose tool tailored for this project. We implemented Willgrind, a debugging tool that checks the behavior of fork-join frame- works implemented by students through dynamic program analysis. Using the Valgrind framework for instrumentation, checking statements are inserted into the code to detect deadlock, ordering violations, and semantic violations at run-time. Additionally, we ex- tended Willgrind with happens-before based checking in WillgrindPlus. -

A Guide to PL/M Programming

INTEL CORP. 3065 Bowers Avenue, Santa Clara, California 95051 • (408) 246-7501 mcs=a A Guide to PL/M programming PL/M is a new high level programming language designed specifically for Intel's 8 bit microcomputers. The new language gives the microcomputer systems program mer the same advantages of high level language programming currently available in the mini and large computer fields. Designed to meet the special needs of systems programming, the new language will drastically cut microcomputer programming time and costs without sacrifice of program efficiency. in addition, training, docu mentation, program maintenance and the inclusion of library subroutines will all be made correspondingly easier. PL/M is well suited for all microcomputer program ming applications, retaining the control and efficiency of assembly language, while greatly reducing programming effort The PL/M compiler is written in ANSI stand ard Fortran I V and thus will execute on most machines without alteration. SEPTEMBER 1973 REV.1 © Intel Corporation 1973 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. INTRODUCTION TO PL/M 1 II. A TUTORIAL APPROACH TO PL/M ............................ 2 1. The Organization of a PL/M Program ........................ 2 2. Basic Constituents of a PL/M Program ....................... 4 2.1. PL/M Character Set ................................ 4 2.2. Identifiers and Reserved Words ....................... 5 2.3. Comments . 7 3. PL/M Statement Organization . 7 4. PL/M Data Elements . 9 4.1. Variable Declarations ............................... 9 4.2. Byte and Double Byte Constants. .. 10 5. Well-Formed Expressions and Assignments . 11 6. A Simple Example. 15 7. DO-Groups. 16 7.1. The DO-WHILE Group ........... -

OS PL/I Optimizing Compiler: CMS User's Guide

SC33-0037 -1 File No. S360/S370-29 OS PL/I Optimizing Compiler: Program Product CMS User's Guide Program Numbers 5734-PL 1 5734-LM4 5734-LM5 (These program products are available as composite package 5734-PL3) §~£Qn~Eg!~!Q~ (June 1973) IThis is a major revision of and obsoletes SC33-0037-0. This edition lapplies to Version 1 Release 2 Modification 0 of the optimizing compiler land to all subsequent releases until otherwise indicated in new editions lor Technical Newsletters. Information has been included on the I facilities that have been introduced with release 2 of the compiler~ and Ion the alterations that have been made -to improve PL/I under CMS. J A number of changes have been made to the compiler options. The COUNT option has been introduced. This results in code being generated that will produce a count of the number of times each statement has been executed during a program. The INCLUDE option has been introduced. This allows secondary text to be included without the overhead of using the complete preprocessor facility. The MARGINS -and SEQUENCE options have been altered so that two default values are set up when the compiler is installed. One value is for F-format records and one for V or U-format records. This simplifies the compilation of source programs with V-format records. A NOSEQUENCE option has been introduced. All these changes are described in chapter 3. Changes have also been made in the execution time options. A method has been introduced whereby they can be specified within the PL/I program.