University High School Summer Reading 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accelerated Reader Book List

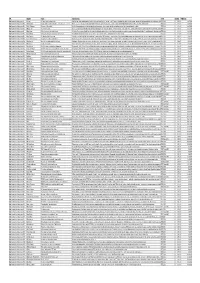

Accelerated Reader Book List Picking a book to read? Check the Accelerated Reader quiz list below and choose a book that will count for credit in grade 7 or grade 8 at Quabbin Middle School. Please see your teacher if you have questions about any selection. The most recently added books/tests are denoted by the darkest blue background as shown here. Book Quiz No. Title Author Points Level 8451 EN 100 Questions and Answers About AIDS Ford, Michael Thomas 7.0 8.0 101453 EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 5.0 9.0 5976 EN 1984 Orwell, George 8.2 16.0 9201 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Clare, Andrea M. 4.3 2.0 523 EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Unabridged) Verne, Jules 10.0 28.0 6651 EN 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila Sprague 4.1 2.0 593 EN 25 Cent Miracle, The Nelson, Theresa 7.1 8.0 59347 EN 5 Ways to Know About You Gravelle, Karen 8.3 5.0 8851 EN A.B.C. Murders, The Christie, Agatha 7.6 12.0 81642 EN Abduction! Kehret, Peg 4.7 6.0 6030 EN Abduction, The Newth, Mette 6.8 9.0 101 EN Abel's Island Steig, William 6.2 3.0 65575 EN Abhorsen Nix, Garth 6.6 16.0 11577 EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Creech, Sharon 4.7 7.0 5251 EN Acceptable Time, An L'Engle, Madeleine 7.5 15.0 5252 EN Ace Hits the Big Time Murphy, Barbara 5.1 6.0 5253 EN Acorn People, The Jones, Ron 7.0 2.0 8452 EN Across America on an Emigrant Train Murphy, Jim 7.5 4.0 102 EN Across Five Aprils Hunt, Irene 8.9 11.0 6901 EN Across the Grain Ferris, Jean 7.4 8.0 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prairie: The Oregon 17602 EN Gregory, Kristiana 5.5 4.0 Trail Diary.. -

Rock 'N' Roll Camp for Girls and Feminist Quests for Equity, Community, and Cultural Production

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses Studies 7-31-2006 I'm Not Loud Enough to be Heard: Rock 'n' Roll Camp for Girls and Feminist Quests for Equity, Community, and Cultural Production Stacey Lynn Singer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Singer, Stacey Lynn, "I'm Not Loud Enough to be Heard: Rock 'n' Roll Camp for Girls and Feminist Quests for Equity, Community, and Cultural Production." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2006. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I’M NOT LOUD ENOUGH TO BE HEARD: ROCK ‘N’ ROLL CAMP FOR GIRLS AND FEMINIST QUESTS FOR EQUITY, COMMUNITY, AND CULTURAL PRODUCTION By STACEY LYNN SINGER Under the Direction of Susan Talburt ABSTRACT Because of what I perceive to be important contributions to female youth empowerment and the construction of culture and community, I chose to conduct a qualitative case study that explores the methods utilized in the performance of Rock ‘n’ Roll Camp for Girls, as well as the experiences of camp administrators, participants, and volunteers, in order to identify feminist constructs, aims, and outcomes of Rock ‘n’ Roll Camp for Girls. -

Impeachment/ Contradictions 3

Huelgas climáticas mundiales 12 Verdaderos crímenes de Trump 12 Workers and oppressed peoples of the world unite! workers.org Vol. 61 No. 41 Oct. 10, 2019 $1 General strike rocks Ecuador By Michael Otto and Zoila Ramirez strike of truckers, bus and taxi drivers Ibarra, Imbabura, Ecuador on Oct. 3-4. That strike by itself para- lyzed the country in the transport unions’ Oct. 7— Support for a call for a general unsuccessful attempt to save the more strike in Ecuador has grown quickly in the than four-decades-old subsidy. past few days, bringing the country to the The national government suspended brink of a change in government. school classes Oct. 3-4, which added The latest upsurge in mass struggle weight to the protests. On Oct. 3, Moreno began after the unpopular President imposed a state of exception, which for Lenín Moreno issued a decree on Oct. 1 the next 60 days nullified the freedoms of ending subsidies for diesel and extra gas- assembly and association (without men- oline with ethanol, fuels used for nearly tioning the constitutional right of resis- all vehicles. Moreno did this following the tance). The state of exception also allowed International Monetary Fund’s require- Moreno to flee his presidential palace in ments for granting Ecuador a loan. Since Quito to the military base in Guayaquil. Oct. 2, many thousands of citizens from The National Assembly is not in ses- PHOTO: TELESUR all social sectors have gone out into the sion, and people don’t know who is actu- A contingent of Indigenous peoples marches to Quito, with 20,000 expected to arrive Oct. -

Riots & Looting in Philadelphia

Joseph C. Gale Commissioner Board of Commissioners Montgomery County, Pennsylvania June 1, 2020 PRESS STATEMENT: RIOTS & LOOTING IN PHILADELPHIA What we saw this weekend in Philadelphia was not a protest - it was a riot. In fact, nearly every major city across the nation was ravaged by looting, violence and arson. The perpetrators of this urban domestic terror are radical left-wing hate groups like Black Lives Matter. This organization, in particular, screams racism not to expose bigotry and injustice, but to justify the lawless destruction of our cities and surrounding communities. Their objective is to unleash chaos and mayhem without consequence by falsely claiming they, in fact, are the victims. For years, our police men and women have been demonized and degraded by the radical left. As a result of this defamation and character assassination, as well as a complicit media constantly pushing the bogus narrative of systemic police brutality and white racism, law enforcement is afraid to do their job of protecting innocent people and their property. In addition, too many Democrat mayors are sympathizers of these far-left radical enemy combatants. As a result, their misguided empathy has enabled a level of unfettered criminality never witnessed before in American history. Sadly, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney falls in this category of sympathetic Democrat mayors. And his handpicked Philadelphia Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw seems to share her boss's sentiment. Frankly, the name Outlaw fits her to a tee. This past weekend, I watched television coverage of police officers being ordered to stand down as the statue of Frank Rizzo was spray painted, lit on fire and attempted to be pulled down. -

Balletx Premieres Short Dance Films About Life in Lockdown by Kristi Yeung

Screenshot courtesy of BalletX BalletX Premieres Short Dance Films About Life in Lockdown by Kristi Yeung How many performances have we lost to coronavirus? I’m sure the list of shows canceled, postponed, and never started would fill many depressing pages. So let’s instead think about something positive: how many works have we gained? The short dance film has become more popular than ever as a result of social distancing. Adding to the growing collection, BalletX recently premiered four videos as part of the Guggenheim’s Virtual Works & Process series. In Caili Quan’s “100 days,” Chloe Perkes embodies the silliness that emerges when your home becomes your whole world. She executes balletic kicks and turns that devolve into hip-swaying grooves as her real-life husband attempts to read in the background. Performing in Hope Boykin’s “…it’s okay too. Feel,” Savannah Green and Ashley Simpson shift between stillness and energetic sequences in rooms made more claustrophobic by split screens and shrinking frames. Penny Saunders’ “Brown Eyes,” featuring Andrea Yorita and Zachary Kapeluck, explores an unstable relationship pushed to its breaking point by confinement. It uses reflections, shadows, and video overlays to intensify the visual tension created by the choreography. The final work to premiere was Rena Butler’s “The Under Way” (working title). Before the pandemic began and George Floyd was tragically killed, BalletX Artistic and Executive Director Christine Cox approached Butler to create a piece about the Underground Railroad. A portion of this work was supposed to premiere live at the Guggenheim museum this spring. -

Racial Terror Lynching, Past and Present Neesha Powell-Twagirumukiza Concepts & Practices of Justice

Enemy Territory By Issue Guest Editor Daniel Tucker The enemy of my enemy is my friend.1 Turn the becomes more ameliorative, but for many proverb around a time or two and you might artists the possibility of using art to engage be able to locate yourself and your allies in the conflict is increasingly urgent. We hope that by confusing terrain of the present. sharing these examples we can all learn what crossing these lines can lead to, and to move The question of how to define an enemy as from healing to accountability. Furthermore, distinct from a friend has been a longstanding knowing this issue was coming out on the preoccupation of politics. Today, some eve of the 2020 elections in the U.S., in the conventions for deciphering alliances have midst of a global coronavirus pandemic, become complicated. For instance, you can’t and in conversation with a wave of uprisings look into someone’s eye or shake their hand against racial injustice, we felt it all the more while safely practicing physical distancing, important to include cultural practitioners and still others are intensified as the ability who may not all define themselves as socially to track a person’s positions through the engaged artists, but who encompass a wide convoluted archive that is the internet. Those range of collaborative creative practices that ideological signposts that render some as seek to confront facist tendencies and redress perpetrators of oppression and others sided the trauma of historical violence. with the angels have also experienced some surprising movements in the current climate Our historical reprint for this issue is Grupo de as fundamental concepts of health and safety Arte Callejero’s (GAC) writing from a decade encourage surprising alliances. -

The Belo Herald Newsletter of the Col

The Belo Herald Newsletter of the Col. A. H. Belo Camp #49, SCV And Journal of Unreconstructed Confederate Thought April 2018 This month’s meeting features a very special program... Mark Brown The Murderous Kansas Red Legs The Belo Herald is an interactive newsletter. Click on the links to take you directly to additional internet resources. Col. A. H Belo Camp #49 Commander - James Henderson 1st Lt. Cmdr. - Open 2nd Lt. Cmdr. - Lee Norman Adjutant - Hiram Patterson Chaplain - Tim Barnes Editor - Nathan Bedford Forrest Contact us: WWW.BELOCAMP.COM http://www.facebook.com/BeloCamp49 Texas Division: http://www.scvtexas.org Have you paid your dues?? National: www.scv.org http://1800mydixie.com/ Come early (6:30pm), eat, fellowship Our Next Meeting: with other members, learn your history! Thursday, April 5th: 7:00 pm La Madeleine Restaurant 3906 Lemmon Ave near Oak Lawn, Dallas, TX *we meet in the private meeting room. "Everyone should do all in his power to collect and disseminate the truth, in the hope that it may find a place in history and descend to posterity." Gen. Robert E. Lee, CSA Dec. 3rd 1865 Commander’s Report Compatriots, The Texas Division State Reunion will be held in Nacogdoches on June 8th thru 10th at the Fredonia Hotel. A social will be held on Friday evening, an awards luncheon on Saturday followed by a banquet on Saturday evening. Our Camp will be allowed one voting delegate for every 10 members. We will need to elect or appoint delegates at our regular monthly meeting this Thursday. Please consider serving in this important function and attending the reunion. -

The Odyssey of the Move Remains

THE ODYSSEY OF THE MOVE REMAINS REPORT OF THE INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATION INTO THE DEMONSTRATIVE DISPLAY OF MOVE REMAINS AT THE PENN MUSEUM AND PRINCETON UNIVERSITY August 20, 2021 Prepared By TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary ...................................................................................................3 II. MOVE in the City of Philadelphia ......................................................................10 A. The History of Philadelphia Police Brutality ..............................................10 B. Frank Rizzo’s Police Department ...................................................................14 C. The Founding and Devolution of MOVE .....................................................17 D. The Original Sin: The Excavation of 6221 Osage Avenue ........................34 III. Why The Demonstrative Display of the MOVE Remains Matters ................40 A. The Samuel Morton Cranial Collection ........................................................41 B. Anthropology, Scientific Racism and Repatriation ....................................45 C. The Origins of the MOVE Remains Controversy .......................................46 IV. The Odyssey of the MOVE Remains: Findings and Conclusions .................56 A. Custody and Storage of the Remains .............................................................56 B. Efforts to Identify and Return the Remains .................................................63 C. Use and Display of the Remains .....................................................................66 -

![714.01 [Cover] Mothernew3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8664/714-01-cover-mothernew3-5108664.webp)

714.01 [Cover] Mothernew3

CMJ NewMusic® CMJ STELLASTARR* 25 REVIEWED: SOUTH, THURSDAY, Report TO MY SURPRISE, SAVES THE DAY, CCMJCMJIssue No.M 832 • SeptemberJ 22, 2003 • www.cmj.com SPOTLIGHT MATCHBOOK ROMANCE + MORE! LOUD ROCK AS HOPE DIES DEAD CRPMMJ VAN DYK GETS REFLECTIVE CMJ RETAIL RAND FINALE! TRUSTTRUST NEVERNEVER SLEEPSSLEEPS Leona Naess Is Bringin’ On The HEARTBREAK RADIO 200: WEEN SPENDS SECOND WEEK AT NO. 1• SPIRITUALIZED HOOKS MOST ADDED NewMusic ® CMJ CMJCMJ Report 25 9/22/2003 Vice President & General Manager Issue No. 832 • Vol. 77 • No. 5 Mike Boyle CEDITORIALMJ COVER STORY Editor-In-Chief 6 A Question Of Trust Kevin Boyce Becoming a hermit in unfamiliar L.A., tossing her computers and letting the guitars bleed in the Associate Editors vocal mics, Leona Naess puts her trust in herself and finally lends her perfect pipes to a record Doug Levy she adores. Now if she could just make journalists come clean and get over her fear of poisoned CBradM MaybeJ Halloween candy… Louis Miller Loud Rock Editor DEPARTMENTS Amy Sciarretto Jazz Editor 4 Essential/Reviews by Dimmu Borgir, Morbid Angel and Dope get Tad Hendrickson Reviews of South, Stellastarr*, Thursday, To My reviewed; Darkest Hour and Atreyu get punked RPM Editor Surprise, Saves The Day, Matchbox Romance on the road; tidbits regarding Slayer, Opeth, and Lost In Translation. Plus, KMFDM’s Angst Exodus, Theatre Of Tragedy, As Hope Dies, Justin Kleinfeld receives CMJ’s “Silver Salute.” Black Dahlia Murder, Stigma, Stampin’ Retail Editor Ground and Josh Homme’s Desert Sessions Gerry Hart 8 Radio 200 series; and Misery Index’s Sparky submits to Associate Ed./Managing Retail Ed. -

ATU Workshop I Amerikansk Historie Stanford Historical

Indholdsfortegnelse – ATU Workshop i Amerikansk Historie Stanford Historical Thinking Chart Jourdon Anderson – ”There never was any pay-day for the Negroes” 1865 Mississippi Black Codes 1865 Alexander Stephens – Cornerstone Address 1861 – (Denne tekst får kun halvdelen af holdet. Den anden halvdel får en anden tekst til en øvelse i tekstformidling) Herald and Advertiser – “The Lynching of Sam Newnan” 1899 John Daniel Davidson, The Federalist – “Why we should keep the confederate monuments right where they are” 2017 Podcast transcript: Into America – “My body is a monument” 2020 Optional reading: David Blight, The New Yorker - “Europe in 1989, America in 2020, and the Death of the Lost Cause” 2020 HISTORICAL THINKING CHART Historical Reading Questions Students should be able to . Prompts Skills • Who wrote this? • Identify the author’s position on • The author probably Sourcing • What is the author’s perspective? the historical event believes . • When was it written? • Identify and evaluate the author’s • I think the audience is . • Where was it written? purpose in producing the • Based on the source • Why was it written? document information, I think the author • Is it reliable? Why? Why not? • Hypothesize what the author will might . say before reading the document • I do/don’t trust this document • Evaluate the source’s because . trustworthiness by considering genre, audience, and purpose • When and where was the document • Understand how context/ • Based on the background created? background information influences information, I understand this Contextualization • What was different then? What was the content of the document document differently the same? • Recognize that documents are because . • How might the circumstances in products of particular points in • The author might have which the document was created time been influenced by _____ affect its content? (historical context) . -

Al Gore 15 Ways to Avert a Climate

URL Speaker Name Short Summary Event Duration Publish date http://www.ted.com/talks/view/id/1 Al Gore 15 ways to avert a climate crisis With the same humor and humanity he exuded in An Inconvenient Truth, Al Gore spells out 15 ways that individuals can address climate change immediately, from buying a hybrid to inventing a new, hotter TED2006"brand name" for global warming. 0:16:17 6/27/2006 http://www.ted.com/talks/view/id/92 Hans Rosling Debunking third-world myths with the best stats you've ever seen You've never seen data presented like this. With the drama and urgency of a sportscaster, statistics guru Hans Rosling debunks myths about the so-called "developing world." TED2006 0:19:50 6/27/2006 http://www.ted.com/talks/view/id/66 Sir Ken Robinson Do schools kill creativity? Sir Ken Robinson makes an entertaining and profoundly moving case for creating an education system that nurtures (rather than undermines) creativity. TED2006 0:19:24 6/27/2006 http://www.ted.com/talks/view/id/53 Majora Carter Greening the ghetto In an emotionally charged talk, MacArthur-winning activist Majora Carter details her fight for environmental justice in the South Bronx -- and shows how minority neighborhood suffer most from flawed urban TED2006policy. 0:00:00 6/27/2006 http://www.ted.com/talks/view/id/7 David Pogue When it comes to tech, simplicity sells New York Times columnist David Pogue takes aim at technology's worst interface-design offenders, and provides encouraging examples of products that get it right. -

1 Exploring the Public Library As a Space for Civil Conversation by Engaging with the Confederate Monument Debate Overview

Exploring the Public Library as a Space for Civil Conversation by Engaging with the Confederate Monument Debate Overview “Many libraries host public programs that facilitate the type of discourse that offers citizens a chance to frame issues of common concern, deliberate about choices for solving problems, create deeper understanding about others’ opinions, connect citizens across the spectrum of thought, and recommend appropriate action that reflects legitimate guidance from the whole community.” (Nancy Kranich) In this activity, students will begin to think about the public library as a space for civil discourse then engage in respectful dialouge surrounding a controversial issue themselves. Students will learn about a community conversation about Confederate monuments held at the Chapel Hill Public Library in August 2017 and using the Civil Conversations Model from the Constitutional Rights Foundation, students will read about then discuss in small groups the controversy surrounding Confederate monuments. (This activity can be conducted as part of a visit to the public library, during which students explore the library as a space for civil discourse, or in the classroom.) Grades 8-12 (teachers will modify the readings provided based on the level of students taught) Materials • Civil Conversations handout, attached o Originally created by the Constitutional Rights Foundation • Anti-Confederate Monument Articles, attached o “Americans should renounce Confederate leaders the same way Germans renounce Hitler” o “Why White Southern Conservatives