Intracerebral Hemorrhage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

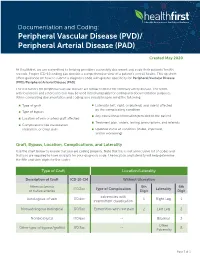

Documentationand Coding Tips: Peripheral Vascular Disease

Documentation and Coding: Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/ Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) Created May 2020 At Healthfirst, we are committed to helping providers accurately document and code their patients’ health records. Proper ICD-10 coding can provide a comprehensive view of a patient’s overall health. This tip sheet offers guidance on how to submit a diagnosis code with greater specificity for Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD). The risk factors for peripheral vascular disease are similar to those for coronary artery disease. The terms arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis may be used interchangeably for coding and documentation purposes. When completing documentation and coding, you should keep in mind the following: Type of graft Laterality (left, right, or bilateral) and side(s) affected by the complicating condition Type of bypass Any educational information provided to the patient Location of vein or artery graft affected Treatment plan, orders, testing, prescriptions, and referrals Complications like claudication, ulceration, or chest pain Updated status of condition (stable, improved, and/or worsening) Graft, Bypass, Location, Complications, and Laterality Use the chart below to ensure that you are coding properly. Note that this is not an inclusive list of codes and that you are required to have six digits for your diagnosis code. The location and laterality will help determine the fifth and sixth digits for the codes. Type of Graft Location/Laterality Description of Graft ICD-10-CM Without -

Peripheral Artery Disease (Pad)

PERIPHERAL ARTERY DISEASE (PAD) Provider’s guide to diagnose and code PAD Peripheral Artery Disease (ICD-10 code I73.9) is estimated The American Cardiology and American Heart Association to affect 12 to 20% of Americans age 65 and older with as 2013 revised guidelines recommend the following many as 75% of that group being asymptomatic (Rogers et al, interpretation for noncompression values for ABI 2011). Of note, for the purposes of this clinical flyer the term (Anderson, 2013). peripheral vascular disease (PVD) is used synonymously with PAD. Table 2: Interpretation of ABI Values Who and how to screen for PAD Value Interpretation The updated 2013 American College of Cardiology and > 1.30 Non-compressible American Heart Association guidelines for the management of 1.00 – 1.29 Normal patients with PAD, recommends screening patients at risk for lower extremity PAD (Anderson et al, 2013). 0.91 – 0.99 Borderline The guidelines recommend reviewing vascular signs and 0.41 - 0.90 Mild to moderate PAD symptoms (e.g., walking impairment, claudication, ischemic 0.00 – 0.40 Severe PAD rest pain and/or presence of non-healing wounds) and physical examination (e.g., evaluation of pulses and inspection The diagnostic accuracy of the ABI can be hindered under the of lower extremities). The Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society following conditions: (Ruff, 2003) Consensus Document on Management of PAD and U.S. Preventative Task Force on screening for PAD identify similar › Patient anxiety and/or discomfort screening criteria that address patient’s age, smoking history, › Poor positioning of patient or restless patient co-morbid conditions and physical exam findings (Moyer, 2013 & Norgren et al, 2007). -

Origin of the Microangiopathic Changes in Diabetes

ORIGIN OF THE MICROANGIOPATHIC CHANGES IN DIABETES A. H. BARNETT Birmingham SUMMARY its glycosidally linked disaccharide units. Such alterations The mechanism of development of microangiopathy is lead to abnormal packing of the peptide chains producing incompletely understood, but relates to a number of excessive leakiness of the membrane. The exact mech ultrastructural, biochemical and haemostatic processes. anisms of thickening and leakiness of basement mem These include capillary basement membrane thickening, brane and their relevance to diabetic complications are not non-enzymatic glycosylation, possibly increased free rad entirely clear, but appear to involve several biochemical ical activity, increased flux through the polyol pathway mechanisms. and haemostatic abnormalities. The central feature Non-enzymatic Glycosylation appears to be hyperglycaemia, which is causally related to the above processes and culminates in tissue ischaemia. In the presence of persistent hyperglycaemia glucose This article will briefly describe these processes and will chemically attaches to proteins non-enzymatically to form discuss possible pathogenic interactions which may lead a stable product (keto amine or Amadori product) of which to the development of the pathological lesion. glycosylated haemoglobin is the best-known example. In long-lived tissue proteins such as collagen the ketoamine Microangiopathy is a specific disorder of the small blood then undergoes a series of reactions resulting in the vessels which causes much morbidity and mortality in dia development of advanced glycosylation end products betic patients. Diabetic retinopathy is the commonest (AGE) (Fig. 1).5 AGE are resistant to degradation and con cause of blindness in the working population of the United tinue to accumulate indefinitely on long-lived proteins. -

Anti-Thrombotics in Stroke When to Start and When to Stop

Anti-Thrombotics In Stroke when to start and when to stop Ania Busza MD PhD Assistant Professor of Neurology University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry No Relevent Disclosures • Research funding from NIH/NICHD (K12 award) • Materials provided for research from MC10, Inc This person was He has afib but was Outlinedischarged 1 week discharged only on ago with a subdural. aspirin – when Should they be back My patient is should I restart his on aspirin? currently on warfarin anticoagulation ? but wants to get pregnant. Is that Common questions that arise post-Stroke safe? Why is everyone The report says talking about putting “likely amyloid TIA patients on angiopathy” – what BOTH aspirin and do I do about their plavix for a few antithrombotics? weeks? Outline ? • Physiology – types of clots and the logic behind the different choices for antithrombotic therapy • Timing: When should antithrombotics be started… – after an ischemic stroke? ? ? – after a hemorrhagic stroke? • Safety: What to consider in selecting antithrombotic therapy – in pregnancy – in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy ? • DAPT: When is duo-antiplatelet treatment indicated? Physiology of Clots thrombosis - an obstruction of blood flow due to a localized occlusive process within one more more blood vessels. Physiology of Clots RED THROMBI WHITE THROMBI RED THROMBI • Erythrocytes + Fibrin • tend to develop in low flow situations: – dilated cardiac atria / afib – regions of ventricular hypokinesia (ventricular aneurysms, low EF, or MI) – leg/pelvic veins -

The Increasing Impact of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy: Essential New

JNNP Online First, published on August 26, 2017 as 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314697 Cerebrovascular disease J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314697 on 26 August 2017. Downloaded from REVIEW The increasing impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: essential new insights for clinical practice Gargi Banerjee,1 Roxana Carare,2 Charlotte Cordonnier,3 Steven M Greenberg,4 Julie A Schneider,5 Eric E Smith,6 Mark van Buchem,7 Jeroen van der Grond,7 Marcel M Verbeek,8,9 David J Werring1 For numbered affiliations see ABSTRact Furthermore, CAA gained new relevance with the end of article. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) has never been advent of anti-Aβ immunotherapies for the treat- more relevant. The last 5 years have seen a rapid ment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as a sizeable Correspondence to increase in publications and research in the field, with proportion of those treated went on to develop Dr David J Werring, The National Hospital for Neurology and the development of new biomarkers for the disease, imaging features of CAA-related inflammation as 5 Neurosurgery, UCL Institute thanks to advances in MRI, amyloid positron emission an unintended consequence. This, together with of Neurology, Queen Square, tomography and cerebrospinal fluid biomarker analysis. advances in our understanding of the impact of London WC1N 3BG, UK; d. The inadvertent development of CAA-like pathology CAA on cognition, in the context of ICH, ageing werring@ ucl. ac. uk in patients treated with amyloid-beta immunotherapy and AD, has broadened the clinical spectrum Received 1 March 2017 for Alzheimer’s disease has highlighted the importance of disease to which the contribution of CAA is Revised 26 April 2017 of establishing how and why CAA develops; without recognised. -

From Brain to Heart: Possible Role of Amyloid-Β in Ischemic Heart Disease and Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review From Brain to Heart: Possible Role of Amyloid-β in Ischemic Heart Disease and Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury Giulia Gagno 1, Federico Ferro 1, Alessandra Lucia Fluca 1, Milijana Janjusevic 1, Maddalena Rossi 1, Gianfranco Sinagra 1, Antonio Paolo Beltrami 2 , Rita Moretti 3 and Aneta Aleksova 1,* 1 Cardiothoracovascular Department, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano Isontina (ASUGI) and University of Trieste, 34100 Trieste, Italy; [email protected] (G.G.); ff[email protected] (F.F.); alessandrafl[email protected] (A.L.F.); [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (G.S.) 2 Department of Medicine (DAME), University of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Internal Medicine and Neurology, Neurological Clinic, 34100 Trieste, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +39-340-550-7762 Received: 3 December 2020; Accepted: 14 December 2020; Published: 17 December 2020 Abstract: Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is among the leading causes of death in developed countries. Its pathological origin is traced back to coronary atherosclerosis, a lipid-driven immuno-inflammatory disease of the arteries that leads to multifocal plaque development. The primary clinical manifestation of IHD is acute myocardial infarction (AMI),) whose prognosis is ameliorated with optimal timing of revascularization. Paradoxically, myocardium re-perfusion can be detrimental because of ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), an oxidative-driven process that damages other organs. Amyloid-β (Aβ) plays a physiological role in the central nervous system (CNS). Alterations in its synthesis, concentration and clearance have been connected to several pathologies, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). -

Diabetic Complications Diabetic Complications

Diabetic Complications Diabetic Complications This is a 15 minute webinar session for CNC physicians and staff CNC holds webinars monthly to address topics related to risk adjustment documentation and coding Next scheduled webinar: • December • Topic: Managing Risk & Quality CNC does not accept responsibility or liability for any adverse outcome from this training for any reason including undetected inaccuracy, opinion, and analysis that might prove erroneous or amended, or the coder/physician’s misunderstanding or misapplication of topics. Application of the information in this training does not imply or guarantee claims payment. American Diabetes Association (ADA) American Diabetes Association (ADA) • Hypoglycemia – in 2011, 282 ED visits for adults who had a first listed diagnosis of hypoglycemia and diabetes as another • Hypertension – in 2009 -2012, of adults with diabetes, 71% had uncontrolled blood pressure • Dyslipidemia – in 2009-2012, of adults with diabetes, 65% had blood LDL cholesterol ≥ 100mg • CVD Death Rates – in 2003-2006, cardiovascular disease was 1.7 times higher in patient with diabetes • Heart Attack Rates – in 2010, heart attach rates were 1.8 times higher in patients with diabetes • Stroke – in 2010, stroke rates were 1.5 times higher in patients with diabetes Diabetes Mellitus E08 E09 E10 E11 E13 • Due to • Drug or • Type 1 • Type 2 • Other underlying chemical specified disease induced Documentation must specify • Type of Diabetes • Type of Complication • Kidney • Ophthalmic • Neurologic postprocedural • Circulatory underlying underlying condition • Skin/Dermatitis/Ulcer poisoning poisoning drug due to st st • Periodontal • Hypo/Hyperglycemia Code 1 • Other Code 1 Genetic defects, defects, Genetic Diabetic Complications Glaucoma People with diabetes are 40% more likely to suffer from glaucoma than people without diabetes. -

Molina Healthcare Coding Education Peripheral Arterial Disease &

Molina Healthcare Coding Education Peripheral Arterial Disease & ABI Documentation Example: Initial Diagnosis Assessment: A 73 year old asymptomatic male with a history of smoking. ABI results 0.90, currently asymptomatic PAD. ICD-10 Code: I73.9 PAD unspecified Plan: Discussed the importance of risk factor control. Will monitor. Measurement of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is reasonable if peripheral arterial Established Diagnosis disease (PAD), also known as peripheral Assessment: A 54 year old diabetic female vascular disease (PVD), is suspected. Although the majority of patients with PAD with stable claudication due to PVD. will not have symptoms, clinical reasons to A1C and BP are currently at goal. suspect PAD include claudication, a non- healing ulcer, skin changes including hair ICD-10 Code: E1151 Type 2 diabetes loss over the lower legs, and age >701. mellitus with diabetic peripheral ABI Interpretation: angiopathy without gangrene ≤0.90 – Abnormal and diagnostic for PAD2 Plan: Discussed the importance of risk factor control, continue anti-platelet agent. Coding Tip: Will monitor. Atherosclerotic vascular disease is a chronic, _______________________________________ progressive disease that should be referred to as current or known PAD/PVD, not history 1J Vasc Surg. 2015 Mar;61(3 Suppl):2S-41S. 2 of PAD/PVD3. Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration. Atherosclerosis. 2006 Nov;189(1):61-9. 3AAPC ICD-10-CM: The Complete Code Set, 2016. Have Questions? Contact: [email protected] The information presented herein is for informational and illustrative purposes only. It is not intended, nor is it to be used, to define a standard of care or otherwise substitute for informed medical evaluation, diagnosis and treatment which can be performed by a qualified medical professional. -

Peripheral Vascular Disease Becomes Increasingly Prevalent with by the Symptom Or Complication (E.G

SePTeMBer 2010 Informative and educational updates for providers FOCUS ON: PerIPherAl Always… • Document the cause of the peripheral arterial disease, VASCUlAr DISeASe if known, as well as the complication (e.g. PAD due to diabetes with ulcer lower leg). • Document arteriosclerosis as “arteriosclerosis of” and the site, “arteriosclerotic” or “arteriosclerosis with,” followed Peripheral vascular disease becomes increasingly prevalent with by the symptom or complication (e.g. arteriosclerosis of age. As such this is a growing concern in the United States given the the lower extremities with rest pain, arteriosclerosis of growing proportion of older adults. Based on a NhANeS report the the lower extremities with ulceration), not the symptom incidence can be as high as 15 to 17% in the population aged 70 and or complication alone. over. Documentation and Coding Tips4 The concern around peripheral vascular disease is several fold: Only a minority of patients may present with the classic symptoms of • “Peripheral arterial disease,” “peripheral vascular disease” limb claudication or ischemia. In one study only about 11 percent of and “intermittent claudication” are coded to 443.9 – the patients with PVD presented with classic symptoms.1 In another Peripheral vascular disease, unspecified. study as many as 28 percent of patients with peripheral vascular • Atherosclerosis of the native arteries of the extremities is disease were found to be physically inactive sometimes due to other coded based on documentation of the condition with the illness thereby precluding the development of symptoms.2 There is a symptom or complication: significant overlap of peripheral vascular disease with coronary artery 440.20 – Atherosclerosis of the extremities, unspecified disease, cerebrovascular disease and abdominal aortic aneurysms. -

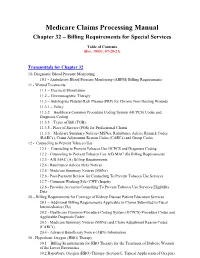

Medicare Claims Processing Manual, Chapter 32, Section 69, and Inpatient Billing Requirements Regarding Acquisition of Stem Cells in Pub

Medicare Claims Processing Manual Chapter 32 – Billing Requirements for Special Services Table of Contents (Rev. 10891, 07-20-21) Transmittals for Chapter 32 10- Diagnostic Blood Pressure Monitoring 10.1 - Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM) Billing Requirements 11 - Wound Treatments 11.1 – Electrical Stimulation 11.2 – Electromagnetic Therapy 11.3 – Autologous Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) for Chronic Non-Healing Wounds 11.3.1 – Policy 11.3.2 – Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) Codes and Diagnosis Coding 11.3.3 – Types of Bill (TOB) 11.3.5 - Place of Service (POS) for Professional Claims 11.3.6 – Medicare Summary Notices (MSNs), Remittance Advice Remark Codes (RARCs), Claim Adjustment Reason Codes (CARCs) and Group Codes 12 - Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use 12.1 - Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use HCPCS and Diagnosis Coding 12.2 - Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use A/B MAC (B) Billing Requirements 12.3 - A/B MAC (A) Billing Requirements 12.4 - Remittance Advice (RA) Notices 12.5 - Medicare Summary Notices (MSNs) 12.6 - Post-Payment Review for Counseling To Prevent Tobacco Use Services 12.7 - Common Working File (CWF) Inquiry 12.8 - Provider Access to Counseling To Prevent Tobacco Use Services Eligibility Data 20 – Billing Requirements for Coverage of Kidney Disease Patient Education Services 20.1 – Additional Billing Requirements Applicable to Claims Submitted to Fiscal Intermediaries (FIs) 20.2 - Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) Procedure Codes and Applicable Diagnosis Codes 20.3 - Medicare Summary -

Vascular Disease Documentation and Coding

Vascular disease documentation and coding Language of documentation Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is more common as people get older. It affects about 8.5 million Americans over the age of 40 and those who smoke or have diabetes are at a higher risk.1,2 “Peripheral arterial disease (PAD),” “peripheral vascular disease (PVD)”, “spasm of artery” and “intermittent claudication” are coded as I73.9. It is important to note that this code excludes atherosclerosis of the extremities (I70.2- – I70.7-). When atherosclerosis (arteriosclerosis) is diagnosed by the clinician, the progress note should state “arteriosclerosis of” and the site including laterality, “arteriosclerotic” or “arteriosclerosis with” followed by the symptom or complication (for example, arteriosclerosis of the legs with intermittent claudication bilaterally). Arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis may be used interchangeably for documentation and coding purposes. Documentation of arteriosclerosis that lacks specificity is coded as I70.90. ICD-10-CM codes Atherosclerosis of native arteries of the extremities (subcategory I70.2-) is further classified as: Use additional code, if applicable, to identify chronic total occlusion of artery of extremity (I70.92) I70.20- Unspecified atherosclerosis of native arteries of extremities » Use a 6th character to identify laterality and/or location: (1) right leg, (2) left leg, (3) bilateral legs, (8) other extremity, (9) unspecified extremity I70.21- Atherosclerosis of native arteries of extremities with intermittent claudication » Use -

Hereditary Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy

Hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy Description Hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy is a condition that can cause a progressive loss of intellectual function (dementia), stroke, and other neurological problems starting in mid-adulthood. Due to neurological decline, this condition is typically fatal in one's sixties, although there is variation depending on the severity of the signs and symptoms. Most affected individuals die within a decade after signs and symptoms first appear, although some people with the disease have survived longer. There are many different types of hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy. The different types are distinguished by their genetic cause and the signs and symptoms that occur. The various types of hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy are named after the regions where they were first diagnosed. The Dutch type of hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy is the most common form. Stroke is frequently the first sign of the Dutch type and is fatal in about one third of people who have this condition. Survivors often develop dementia and have recurrent strokes. About half of individuals with the Dutch type who have one or more strokes will have recurrent seizures (epilepsy). People with the Flemish and Italian types of hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy are prone to recurrent strokes and dementia. Individuals with the Piedmont type may have one or more strokes and typically experience impaired movements, numbness or tingling (paresthesias), confusion, or dementia. The first sign of the Icelandic type of hereditary cerebral amyloid angiopathy is typically a stroke followed by dementia. Strokes associated with the Icelandic type usually occur earlier than the other types, with individuals typically experiencing their first stroke in their twenties or thirties.