Chicago Journal of Foreign Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

READ It Here

AN INDEPENDENT PUBLICATION VOLUME 3 | ISSUE 1 |SUMMER 2021 EDITORIAL BOARD Editors-in-Chief Gregory Wong University of Chicago Ethan McAndrews Indiana University, Bloomington Political Culture Ian Wong University of California, Berkeley Ari Fahimi University of California, Los Angeles Kedar Pandya Texas A&M University Political Science Zhenqi Hu Stanford University Molly McNutt Barnard College Nicholas Romanow University of Texas, Austin Matt Sheppard University of Chicago Political Economy & Business Troy Shen Stanford University David Liu University of Chicago Isabelle Bennett Indiana University, Bloomington Production Ari Fahimi University of California, Los Angeles Ian Wong University of California, Berkeley JOURNAL OF SINO-AMERICAN AFFAIRS I LETTER FROM THE EDITORS As Editors-in-Chief of JOSA over the past year, we’ve kept a secret. By its nature, this Journal holds very little room for unspoken motives. JOSA was born out of trust between Stanford and Berkeley students–an idea so promising it transcended collegiate rivalry and undergrad bacchana- lia alike. But nonetheless, a silent goal was formed, recognizable at first only between the two of us. Since the start of our tenure, we’ve worked to steer the Journal in a new direction. JOSA’s original, stated mission has never faded. We’ve always aimed to provide sharp insight on the US -Chi- na relationship, and in the process, provide a platform to highlight young leaders from both sides of the Pacific. Over the past three years, we’ve featured undergraduate and graduate work from Tsinghua to Stanford, hosted several speaking events with prominent thought leaders, and evolved into the largest student-run US-China journal in the United States. -

“China Factor” in Contemporary Hong Kong Genre Cinema

Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies 46.1 March 2020: 11-37 DOI: 10.6240/concentric.lit.202003_46(1).0002 Re-Negotiations of the “China Factor” in Contemporary Hong Kong Genre Cinema Ting-Ying Lin Department of Information and Communication Tamkang University, Taiwan Abstract Given the long-existing and multifaceted negotiations of the “China factor” in Hong Kong film history, this article centers on the political function of genre films by exploring how contemporary Hong Kong filmmakers utilize filmmaking as a flexible strategy to re-negotiate and reflect on the China factor concerning current post-handover political dynamics. By focusing on several recent Hong Kong genre films as case studies, it examines how the China factor is negotiated in Vulgaria (低俗喜劇 Disu xiju, 2012) and The Midnight After (那夜凌晨,我坐上了旺角開往大埔的紅 VAN Naye lingchen, wo zuoshang le Wangjiao kaiwang Dapu de hong van, 2014), considering the politics of languages alongside the imaginary of the disappearance of Hong Kong’s local cultures in the post-handover era. It also highlights two post-Umbrella- Revolution films, Trivisa ( 樹大招風 Shuda zhaofeng, 2016) and The Mobfathers (選老頂 Xuan lao ding, 2016), to explore how the China factor is negotiated in light of the collective anxieties of Hongkongers regarding the handover and controversies in the current electoral system of Hong Kong. By doing so, this article argues that the re-negotiations of the China factor in contemporary Hong Kong genre cinema have become more and more politically reflexive given the increasingly severe political interference of the Beijing sovereignty that has violated the autonomy of Hong Kong, while forming a discourse of resistance of Hongkongers against possible neo- colonialism from the Chinese authorities in the postcolonial city. -

We're a Proud Sponsor of the San Diego Asian Film Festival

21ST ANNUAL SAN DIEGO SAN ASIAN SAN DIEGO FILM DIEGO ASIAN FILM FESTIVAL 2020 FESTIVAL ASIAN PRESENTED BY: / OCT FILM 23—31 WWW.PACARTS.ORG @PACARTSMOVEMENT 2020 FESTIVAL SDAFF.ORG 23—31 23—31 22020020 FESTIVAL OCTOBER OCTOBER FILM PRESENTED ASIAN DIEGO BY PACIFIC SAN ARTS 125 FILMS 50 Q&AS MOVEMENT 34 LANGUAGES 24 COUNTRIES About the design: 2020 is the year of eyes. That’s all we see of anybody, whether peering over masks. Or from the protests in HK and US, masses of people looking back hard at our leaders. Or staring at screens for school, work, and now, the worlds of The Boat People 42 Inches From Covid 45 Providence 42 film. This year’s kinetic graphics are inspired by the “dazzle [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] camouflage” used on boats in WWI to create visual confusion A Bright Summer Diary 42 Junipero Serra 45 Radical Care: The Auntie Sewing Squad 9 through hypervisibility, a strategy later adopted by modern [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] day activists to deter facial recognition. Lastly, on our print publications is ZXX, an anti-surveillance typeface designed Can't judge~Corona and the Japanese Kama'āina (Child of the Land) 41 Red Aninsri; Or, Tiptoeing on by Sang Mun as a call-to-action to raise questions about our government 20XX version~ 47 [email protected] The Still Trembling Berlin Wall 44 [email protected] [email protected] online privacy. This typeface purposefully misdirects information Kapaemahu 41 and confuses text scanning software. -

Official Record of Proceedings

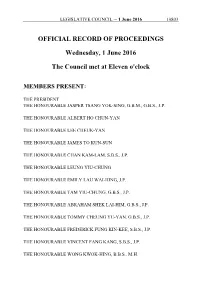

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 10803 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 1 June 2016 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. 10804 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 1 June 2016 PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LEUNG KA-LAU THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG KWOK-CHE THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-KIN, S.B.S. -

Consensus: BC Parking Must Be Worked

'-'!~- ~-.'1 . BETHLEHEM PUBLIC LIBR/\PV DO NOT CIRCU~ zooo Rockwell1s BLG hosts 2.~0£-~~02-t AN ~~Wl3G . 3~~ 3~~M~l30 l£~ A!!~Ha Il ::J nand W3H3lHl39 notor1ety hockey· tourney d&L M0t 00-t0-E>0 £~0£ Oseepage26 0 see page 18 • WMI3************************ ----------------- .- Consensus: BC parking .. ·Lemonade brigade .. must be worked out By JOSEPH A. PHILLIPS consideration, were only short-term salution to a long-term problem. It is one More than 150 residents packed that, several speakers warned, is not Bethlehem town hall auditorium for a limited to students or to the school day. town board meeting last Wednesday, Said Grantwood resident lisa Gruber, "I where the controversy over student favor this proposition - but only on parking in the neighborhoods adjacent condition that the bigger picture is also to Bethlehem Central High School addressed." · topped the agenda. The high school's facilities have seen At issue: a public hearing on proposed growing round-the-clock and all-season new parking-restrictions for Grantwood · use by a broad Avenue, a side ________________ctosssectionofthe ·:·srreet in the community ~B r o o k f i e I d I'Ve asked that thiS be a senior citizens development that . , participating in "faces the high permanen t so Iu t ton, so we re open swimming .'school across not constantly having meetings programs; families Delaware Avenue. The one-hour attending soccer on parking issues. Dr. Loomis tournaments; parking limit on has agreed. Sheila Fuller participants in Grantwood during _________...., ______ open houses, school hours was summer aimed squarely at recreational programs and evening and student drivers who have taken in after-school activities - all of which growing numbers to parking on the occasionally overwhelm available shoulders of that narrow side street this parking space. -

312648638.Pdf

PROSEDUR ISI HARDDISK 1. Pilih PC Game dan Movie yang mau diisi dari List excel ini dengan cara ketik 1 pada kolom order 2. Kirimkan List Excel ini ke email [email protected] 3. Kirim Harddisk ke alamat kami, bisa COD atau Kirim via JNE. 4. Harddisk kami terima, kami proses menurut antrian jika sedang ramai 5. Jika sudah selesai, lakukan pembayaran lunas. 6. Harddisk kami kirim kembali ke tempat anda. Minimal Transaksi Rp 50.000,-. Dibawah itu tetap dikenakan Rp 50.000,-. Jika ingin datang langsung untuk memberikan harddisknya, bisa datang ke toko partner kami, lihat sheet prosedur dibawah Untuk Harddisk External. Kirimkan juga Kabel dan Powernya (kalo ada). HDD Internal tambah Rp 15.000,- TARIF PENGISIAN HARDDISK Ringkasan Order MOVIE ITEM Movie Rp 1.000,- / MOVIE PC Game TOTAL PC GAME Data diatas terisi otomatis. Blm termasuk ongkir Rp 2.000,- / PC GAME Tulis Data Anda Minimal Transaksi Rp 50.000,-. Dibawah itu tetap dikenakan Rp 50.000,-. Jika ingin datang langsung untuk memberikan harddisknya, bisa datang ke toko partner kami, lihat sheet prosedur dibawah Nama No Tlp Untuk Harddisk External. Kirimkan juga Kabel dan Powernya (kalo ada). HDD Internal tambah Rp 15.000,-Alamat Kirim Hubungi Kami SMS Only : 085780605001 Blackberry PIN : 7CA3D7FD Catatan Email : [email protected] Website : www.onelinepcgame.com Thread Kaskus : http://kaskus.onelinepcgame.com ID Kaskus : hackerezim Ringkasan Order ITEM JML Harga Rp Movie 0 IDR 0 PC Game 0 IDR 0 TOTAL 0 IDR 50000 Data diatas terisi otomatis. Blm termasuk ongkir Tulis Data Anda -

Basic Cantonese: a Grammar and Workbook

BASIC CANTONESE: A GRAMMAR AND WORKBOOK Basic Cantonese introduces the essentials of Cantonese grammar in a straightforward and systematic way. Each of the 28 units deals with a grammatical topic and provides associated exercises, designed to put grammar into a communicative context. Special attention is paid to topics which differ from English and European language structures. Features include: • clear, accessible format • lively examples to illustrate each grammar point • informative keys to all exercises • glossary of grammatical terms Basic Cantonese is ideal for students new to the language. Together with its sister volume, Intermediate Cantonese, it forms a structured course of the essentials of Cantonese grammar. Virginia Yip is Associate Professor at the Department of Modern Languages and Intercultural Studies, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Stephen Matthews lectures in the Department of Linguistics at the University of Hong Kong. They are the authors of Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar (1994). Titles of related interest published by Routledge: Basic Chinese: A Grammar and Workbook By Yip Po-Ching and Don Rimmington Intermediate Chinese: A Grammar and Workbook By Yip Po-Ching and Don Rimmington Chinese: An Essential Grammar By Yip Po-Ching and Don Rimmington Colloquial Chinese By Qian Kan Colloquial Chinese (Reprint of the first edition) By Ping-Cheng T’ung and David E.Pollard Colloquial Chinese CD Rom By Qian Kan Colloquial Cantonese By Gregory James and Keith S.T.Tong Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar By Stephen Matthews and Virginia Yip BASIC CANTONESE: A GRAMMAR AND WORKBOOK Virginia Yip and Stephen Matthews London and New York First published 2000 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

A Tale Too Well Told

MARCH/APRIL 2016 VOL. 88 | NO. 3 JournalNEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION A Tale Too Well Told The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial and the Also in this Issue Cross-Examination of Kate Alterman UM/UIM/SUM Law and Practice By Harold Lee Schwab The Double-Edged Sword of Autofill Life Insurance and Retirement Plan Benefits MacPherson Turns 100 Tax-Advantaged Investing in Booming ASEAN Economies High growth. Low cost. If you are like most solo and small firms, growing your practice feels like a daunting challenge. How do you identify and acquire the right kinds of clients, provide the services those clients need in a way that adds value, and ensure prompt payment? On top of that, in order for your firm to thrive, you need to grow profits. Luckily, there’s a solution—Clio. Grow your law firm. Focus on practicing law. Let Clio take care of the rest. Start your free trial today at Clio.com Grow your practice. Clio® and the Clio Checkmark Logo™ are trademarks or registered trademarks of Themis Solutions Inc. ©2015 Themis Solutions Inc. All rights reserved. BESTSELLERS FROM THE NYSBA BOOKSTORE March/April 2016 Attorney Escrow Accounts – Rules, Disability Law and Practice: Book Two New York Contract Law: A Guide for Regulations and Related Topics, 4th Ed. The second of a three-book series focuses on Non-New York Attorneys Fully updated, this is the go-to guide on escrow Financial and Health Care Benefits and Future A practical, authoritative reference for questions funds and agreements, IOLA accounts and the Planning. and answers about New York contract law. -

A Conductor's Guide to Lyric Diction in Standard Chinese

A Conductor’s Guide to Lyric Diction in Standard Chinese by Yik Ling Elaine Choi A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Elaine Choi, 2018. A Conductor’s Guide to Lyric Diction in Standard Chinese Yik Ling Elaine Choi Doctor of Musical Arts Faculty of Music University of Toronto 2018 Abstract Chinese choral music is a relatively recent phenomenon. Within the last century, Chinese conductors and choral ensembles have actively fostered a vibrant choral community. Furthermore, Chinese composers have taken increasing interest in the choral art, resulting in a growing body of new choral repertoire. Contemporary Chinese choral music adopts western choral approaches such as voice parts (SATB), style (bel canto), harmony and structure, but retains Chinese texts. In order to introduce Chinese choral art music to English-speaking choirs, conductors must be equipped with good resources to deepen their understanding of the choral culture in China. More importantly, they need supportive materials to help them tackle the challenges of the language. Currently there are few guides to lyric diction in Standard Chinese for singers and choral conductors. The primary goal of this study is to break down the complexity of the pronunciation of this language, using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) and Pinyin systems, to provide a helpful guide to conductors in teaching Chinese choral music. ii A secondary goal is to introduce choral musicians to contemporary Chinese choral music. In addition to outlining the history of choral music in China, this study also includes analyses of five original compositions written within the last decade, in order to provide examples of original choral works in Standard Chinese written by Chinese composers from different geographical backgrounds: Hong Kong, China, the United States, and Canada. -

Keterangan : (Read!!!!!) 1

KETERANGAN : (READ!!!!!) 1. No Minimal Order 2. Menerima Request Film 3. Kesalahan dalam Penulisan Alamat Tujuan Pengiriman Bukan Tanggung Jawab Seller 4. Film hanya dapat di Play di Komputer / Laptop / Tablet / Android 5. Proses Pengerjaan 1-2 hari 6. Kualitas Gambar 95% Film sudah Blu-ray 720p & 1080p 7. 95% Film Sudah menggunakan Subtittle Berbahasa Indonesia. CARA ORDER 1. Download List Film "Bang Filem Mks Movie" 2. Pilih Film yang di inginkan dengan mengetik huruf " x " di kolom "Order" 3. Isi Data Diri anda di bagian "Pengisian Form Order" 4. Save File Excel yang sudah di lengkapi Data Diri anda 5. Kirim File Excel Ke Alamat E-mail : [email protected] Pengisian Form Order Nama Lengkap Alamat Lengkap & Kode Pos No. Hp E-mail Catatan Setelah di Save, Kirim File Excel ini ke : [email protected] Movie Catalog ada di Sheet 2 ( Lihat Bagian Pojok Kiri Bawah ) twitter : @bangfilemmks sms : 0896-999-14054 email: [email protected] blog: bangfilemmks.blogspot.com Pengisian Form Order Setelah di Save, Kirim File Excel ini ke : [email protected] Movie Catalog ada di Sheet 2 ( Lihat Bagian Pojok Kiri Bawah ) twitter : @bangfilemmks (untuk respon cepat) email: [email protected] blog: bangfilemmks.blogspot.com Bang_filem_MKs No. Title 1 13 Sins 2 2 States 3 22 Jump Street 4 3 A.M. 3D: Part 2 5 3 Days to Kill 6 300: Rise of an Empire 7 A Fighting Man 8 A Good Marriage 9 A Haunted House 2 10 A Million Ways To Die In The West 11 A Voodoo Possession 12 A Walk Among Tombstones 13 Age of Tomorrow 14 Alien Abduction 15 -

Syllable Fusion in Hong Kong Cantonese Connected Speech

SYLLABLE FUSION IN HONG KONG CANTONESE CONNECTED SPEECH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Wai Yi Peggy Wong, B.A., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Professor Mary E Beckman, Adviser _________________________ Professor Marjorie K M Chan, Co-Adviser Adviser Professor Chris Brew _________________________ Co-Adviser Linguistics Graduate Program © Copyright by Wai Yi Peggy Wong 2006 ABSTRACT This dissertation is about “syllable fusion” in Hong Kong Cantonese. Syllable fusion is a connected-speech phenomenon whereby boundaries between syllables are blurred together in a way that suggests an intermediate level of grouping between the syllable and the larger intonational phrase. Previous studies of this phenomenon have focused on extreme cases — i.e. whole segments (consonants and/or vowels) are deleted at the relevant syllable boundary. By contrast, in this dissertation, “syllable fusion” refers to a variety of changes affecting a sequence of two syllables that range along a continuum from “mild” to “extreme” blending together of the syllables. Less extreme changes include assimilation, consonant lenition and so on, any substantial weakening or effective deletion of the oral gesture(s) of the segment(s) contiguous to the syllable boundary, and the sometimes attendant resyllabifications that create “fused forms”. More extreme fusion can simplify contour tones and “merge” the qualities of vowels that would be separated by an onset or coda consonant at more “normal” degrees of disjuncture between words. ii The idea that motivates the experiments described in this dissertation is that the occurrence of syllable fusion marks prosodic grouping at the level of the “foot”, a phonological constituent which has been proposed to account for prosodic phenomena such as the process of tone sandhi and neutral tone in other varieties of Chinese.