Mass Digitization of Chinese Court Decisions: How to Use Text As Data in the Field of Chinese Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

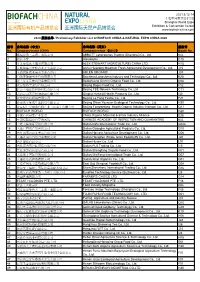

(CHN) 公司名称(英文) Company Name (ENG)

2021.5.12-14 上海世博展览馆3号馆 Shanghai World Expo Exhibition & Convention Center www.biofach-china.com 2020 展商名单 / Preliminary Exhibitor List of BIOFACH CHINA & NATURAL EXPO CHINA 2020 编号 公司名称(中文) 公司名称(英文) 展位号 No. Company name (CHN) Company name (ENG) Booth No. 1 雅培贸易(上海)有限公司 ABBOTT Laboratories Trading (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. N/A 2 阿拉小优 Alaxiaoyou C15 3 江苏安舜技术服务有限公司 ALEX STEWART (AGRICULTURE) CHINA LTD. H15 4 安徽华栋山中鲜农业开发有限公司 Anhui Huadong Mountain Fresh Agricultural Development Co., Ltd. J15 5 上海阿林农业果业专业合作社 ARLEN ORGANIC J01 6 白城市隆盛实业科技有限公司 Baicheng Longsheng Industry and Technology Co., Ltd. K20 7 北大荒亲民有机食品有限公司 Beidahuang Qinmin Organic Food Co., Ltd. E08 8 北京佰格士食品有限公司 Beijing Bages Food Co., Ltd. F12 9 北京中福必易网络科技有限公司 Beijing FBE Network Technology Co.,Ltd. C11 10 青海可可西里保健食品有限公司 Qinghai Kekexili Health Products Co., Ltd. I30 11 北京乐坊纺织品有限公司 Beijing Le Fang Textile Co., Ltd. F21 12 北京食安优选生态科技有限公司 Beijing Shian Youxuan Ecological Technology Co., Ltd. H30 13 北京同仁堂健康有机产业(海南)有限公司 Beijing Tongrentang Health Organic Industry (Hainan) Co., Ltd. Q11 14 BIOFACH WORLD BIOFACH WORLD G20 15 中国有机母婴产业联盟 China Organic Maternal & Infant Industry Alliance E25 16 中国检验检疫科学研究院 CHINESE ACADEMY OF INSPECTION AND QUARANTINE N/A 17 大连大福国际贸易有限公司 Dalian Dafu International Trade Co., Ltd. G02a 18 大连广和农产品有限公司 Dalian Guanghe Agricultural Products Co., Ltd. G10 19 大连盛禾谷农业发展有限公司 Dalian Harvest Agriculture Development Co., Ltd. G06 20 大连弘润全谷物食品有限公司 Dalian HongRen Whole Grain Foodstuffs Co., Ltd. J20 21 大连华恩有限公司 Dalian Huaen Co., Ltd. L01 22 大连浦力斯国际贸易有限公司 Dalian PLS Trading Co., Ltd. I15 23 大连盛方有机食品有限公司 Dalian Shengfang Organic Food Co., Ltd. H01 24 大连伟丰国际贸易有限公司 Dalian WeiFeng International Trade Co., Ltd. G07 25 大连鑫益农产品有限公司 Dalian Xinyi Organics Co., Ltd. -

Loan Agreement

CONFORMED COPY LOAN NUMBER 4829-CHA Public Disclosure Authorized Loan Agreement (Henan Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Project) Public Disclosure Authorized between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA and Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Dated September 1, 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized LOAN NUMBER 4829-CHA LOAN AGREEMENT AGREEMENT, dated September 1, 2006, between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (the Borrower) and INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (the Bank). WHEREAS (A) the Borrower, having satisfied itself as to the feasibility and priority of the project described in Schedule 2 to this Agreement (the Project), has requested the Bank to assist in the financing of the Project; (B) the Project will be carried out by Henan (as defined in Section 1.02) with the Borrower’s assistance and, as part of such assistance, the Borrower will make the proceeds of the loan provided for in Article II of this Agreement (the Loan) available to Henan, as set forth in this Agreement; and WHEREAS the Bank has agreed, on the basis, inter alia, of the foregoing, to extend the Loan to the Borrower upon the terms and conditions set forth in this Agreement and in the Project Agreement of even date herewith between the Bank and Henan (the Project Agreement); NOW THEREFORE the parties hereto hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I General Conditions; Definitions Section 1.01. The “General Conditions Applicable to Loan and Guarantee Agreements for Single Currency Loans” of the Bank, dated May 30, 1995 (as amended through May 1, 2004) with the following modifications (the General Conditions), constitute an integral part of this Agreement: (a) Section 5.08 of the General Conditions is amended to read as follows: “Section 5.08. -

Resettlement Monitoring Report: People's Republic of China: Henan

Resettlement Monitoring Report Project Number: 34473 December 2010 PRC: Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project – Resettlement Monitoring Report No. 8 Prepared by: Environment School, Beijing Normal University For: Henan Province Project Management Office This report has been submitted to ADB by Henan Province Project Management Office and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s public communications policy (2005). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project Financed by Asian Development Bank Monitoring and Evaluation Report on the Resettlement of Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (No. 8) Environment School Beijing Normal University, Beijing,China December , 2010 Persons in Charge : Liu Jingling Independent Monitoring and : Liu Jingling Evaluation Staff Report Writers : Liu Jingling Independent Monitoring and : Environment School, Beijing Normal University Evaluation Institute Environment School, Address : Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China Post Code : 100875 Telephone : 0086-10-58805092 Fax : 0086-10-58805092 E-mail : jingling @bnu .edu.cn Content CONTENT ...........................................................................................................................................................I 1 REVIEW .................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 PROJECT INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. -

Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China

Country Report for the Preparation of the First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China June 2003 Beijing CONTENTS Executive Summary Biological diversity is the basis for the existence and development of human society and has aroused the increasing great attention of international society. In June 1992, more than 150 countries including China had jointly signed the "Pact of Biological Diversity". Domestic animal genetic resources are an important component of biological diversity, precious resources formed through long-term evolution, and also the closest and most direct part of relation with human beings. Therefore, in order to realize a sustainable, stable and high-efficient animal production, it is of great significance to meet even higher demand for animal and poultry product varieties and quality by human society, strengthen conservation, and effective, rational and sustainable utilization of animal and poultry genetic resources. The "Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China" (hereinafter referred to as the "Report") was compiled in accordance with the requirements of the "World Status of Animal Genetic Resource " compiled by the FAO. The Ministry of Agriculture" (MOA) has attached great importance to the compilation of the Report, organized nearly 20 experts from administrative, technical extension, research institutes and universities to participate in the compilation team. In 1999, the first meeting of the compilation staff members had been held in the National Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Service, discussed on the compilation outline and division of labor in the Report compilation, and smoothly fulfilled the tasks to each of the compilers. -

Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management

THIS DOCUMENT IS IN DRAFT FORM, INCOMPLETE AND SUBJECT TO CHANGE AND THE INFORMATION MUST BE READ IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE SECTION HEADED “WARNING” ON THE COVER OF THIS DOCUMENT. DIRECTORS, SUPERVISORS AND SENIOR MANAGEMENT BOARD OF DIRECTORS App1A-41(1) The Board consists of eleven Directors, including five executive Directors, two non-executive 3rd Sch 6 Directors and four independent non-executive Directors. The Directors are elected for a term of three years and are subject to re-election, provided that the cumulative term of an independent non-executive Director shall not exceed six years pursuant to the relevant PRC laws and regulations. The following table sets forth certain information regarding the Directors. Time of Time of joining the joining the Thirteen Date of Position held Leading City Time of appointment as of the Latest Group Commercial joining the as a Practicable Name Age Office Banks Bank Director Date Responsibility Mr. DOU 54 December N/A December December Executive Responsible for the Rongxing 2013 2014 23, 2014 Director, overall management, (竇榮興) chairperson of strategic planning and the Board business development of the Bank Ms. HU 59 N/A January 2010 December December Executive In charge of the audit Xiangyun (Joined 2014 23, 2014 Director, vice department, regional (胡相雲) Xinyang chairperson of audit department I and Bank) the Board regional audit department II of the Bank Mr. WANG Jiong 49 N/A N/A December December Executive Responsible for the (王炯) 2014 23, 2014 Director, daily operation and president management and in charge of the strategic development department and the planning and financing department of the Bank Mr. -

E- 304 Bz21vk,4X=Vol

E- 304 BZ21VK,4X=VOL. 8 CLASS OF EM CERTIFICATE CLASS,A EIA CERTIFICATENO A0948 Public Disclosure Authorized HNNHGlGWfAY PROJECTUM INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTALACTION PLAN Public Disclosure Authorized AccE(CO/ SCNNE IECP FL C/Ih/Pr hl%eor #) LaNCrGtR'T ESW Co~'Pg Aon i'wC Public Disclosure Authorized HENAN INSTITUTE OF ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION November, 1999 l CLASSOF EIA CERTIFICATE: CLASS A EIA CERTIFICATENO.: A 0948 HENAN HIGHWAY PROJECT ITI I HIGIWAY NETWORK UPGRADING PROECT INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION PLAN HENAN INSTITUTE OF ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION November, 1999 HENANHIGHWAY PROJECT HI HIGHWAYNETWORK UPGRADINGPROJECT INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACTION PLAN I Prepared by: Henan Institute of Environment Protection Director: Meng Xilin Executive Vice Director: Shi Wei (Senior Engineer) J Executive Vice Chief Engineer: Huang Yuan (Senior Engineer) EIA Team Leader: HuangYuan (EIA License No. 006) Principal Engineer: Shao Fengshou (EIA License NO. 007) EIA Team Vice Leader: Zhong Songlin (EIA License No. 03509) Task Manager: Yi Jun (EIA License No. 050) Participants: Yi Jun (EIA License No. 050 Wang Pinlei (EIA License No. 03511) Fan Dongxiao (Engineer) IJ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PROJECT BRIEF ......................................................... 1 1.1 Project Components and Descriptions ..................................................1 1.2 Project Features ......................................................... 3 1.3 Project Schedule -

World Bank Document

CONFORMED COPY LOAN NUMBER 7909-CN Public Disclosure Authorized Project Agreement Public Disclosure Authorized (Henan Ecological Livestock Project) between INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT Public Disclosure Authorized and HENAN PROVINCE Dated July 26, 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT AGREEMENT AGREEMENT dated July 26, 2010, entered into between INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT (the “Bank”) and HENAN PROVINCE (“Henan” or the “Project Implementing Entity”) (“Project Agreement”) in connection with the Loan Agreement of same date between PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (“Borrower”) and the Bank (“Loan Agreement”) for the Henan Ecological Livestock Project (the “Project”). The Bank and Henan hereby agree as follows: ARTICLE I – GENERAL CONDITIONS; DEFINITIONS 1.01. The General Conditions as defined in the Appendix to the Loan Agreement constitute an integral part of this Agreement. 1.02. Unless the context requires otherwise, the capitalized terms used in the Project Agreement have the meanings ascribed to them in the Loan Agreement or the General Conditions. ARTICLE II – PROJECT 2.01. Henan declares its commitment to the objective of the Project. To this end, Henan shall: (a) carry out the Project in accordance with the provisions of Article V of the General Conditions; and (b) provide promptly as needed, the funds, facilities, services and other resources required for the Project. 2.02. Without limitation upon the provisions of Section 2.01 of this Agreement, and except as the Bank and Henan shall otherwise agree, Henan shall carry out the Project in accordance with the provisions of the Schedule to this Agreement. ARTICLE III – REPRESENTATIVE; ADDRESSES 3.01. -

2019展商名单/Preliminary Exhibitor List Of

2019.5.16-18 Shanghai World Expo Exhibition & Convention Center www.biofach-china.com 2019展商名单 /Preliminary Exhibitor List of BIOFACH CHINA 2019 编号 公司名(中文) 公司名(英文) 展位号 No Company Name (Chi) Company Name (Eng) Booth No. 1 0+蛋糕 0+cake H08 2 上海市金山区农业农村委员会 Agricultural Committee of Jinshan District, Shanghai Municipality A55 3 阿军轻蔬食 Ajun Light Vegetable Food F01 4 阿拉尔新农乳业有限责任公司 Ala'er Xinnong Dairy Co., Ltd. A65 5 红醇坊企业有限公司 Alarcon Enterprise Limited C66 6 阿勒泰益康有机面业有限公司 Aletai Yikang Organic Noodle Co., Ltd. A65 7 江苏安舜技术服务有限公司 Alex Stewart (Agriculture) China. Ltd. A55 8 ALTERFOOD ALTERFOOD A15 9 AMA TIME AMA TIME D22 10 Amazing Cacao Amazing Cacao F15 11 Arla Foods Arla Foods A25&B20 12 阿林农业科技有限公司 ARLEN ORGANIC A55 13 阿蒂米斯橄榄油 Artemis olive oil F01 14 雅士利乳业(马鞍山)销售有限公司 Ashley Dairy (Ma'an Mountain) Sales Co., Ltd. A20 15 阿丝道食品 Asidao Food F01 16 Avonmore Estate Biodynamic Wines Pty Ltd Avonmore Estate Biodynamic Wines Pty Ltd C31 17 白城市隆盛实业科技有限公司 Baiheng Longsheng Industry and Technology Co., Ltd. D36 18 爵霸(上海)贸易有限公司 Bebebalm E08i 19 零榆环保材料科技(常熟)有限公司 BEEZIRO E08j 20 北大荒亲民有机食品有限公司 BEIDAHUANG QINMIN ORGANIC FOOD CO., LTD. C50 21 北京清源保生物科技有限公司 Beijing Kingbo Biotech Co., Ltd. E31 22 北京春播科技有限公司 Beijing Chunbo Technology Co., Ltd. D68 23 北京五洲恒通认证有限公司 Beijing Continental Hengtong Certification Co., Ltd. C80 24 北京中合金诺认证中心有限公司 BEIJING CO-OPS INTEGRITY CERTIFICATION CENTRE B83 25 北京德睿伟业国际贸易有限公司 Beijing Dairy International Trade Co., Ltd. D52 26 北京爱科赛尔认证中心有限公司 Beijing Ecocert Certification Center Co., Ltd. C52 27 北京乐坊纺织品有限公司 Beijing Le Fang Textile Co., Ltd. D29 28 北京天彩纺织服装有限公司 Beijing Rainbow Textiles & Garments Co., Ltd. B65 29 北京双娃乳业有限公司 Beijing SUVOW Dairy Co., Ltd. -

Economic Analysis of Fuel Collection, Storage, and Transportation in Straw Power Generation in China

Energy 132 (2017) 194e203 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/energy Economic analysis of fuel collection, storage, and transportation in straw power generation in China * Yufeng Sun , Wenchao Cai, Bo Chen, Xueying Guo, Jianjun Hu, Youzhou Jiao College of Mechanical & Electrical Engineering, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, 450002, China article info abstract Article history: Biomass power generation projects involve green and renewable energy. This study regards Laifa Straw Received 12 April 2016 Recycling Company of Henan Sheqi as an example. Field survey and economic analysis are employed as Received in revised form the main research methods. The problems of straw collection, storage, and transportation are examined. 11 May 2017 According to the data obtained from the investigation and the mathematical model, when the straw Accepted 12 May 2017 recycling company uses the artificial model, the average price of each ton of straw is 385.4 yuan; when Available online 16 May 2017 the straw recycling company uses the mechanical model, the average price of each ton of straw is 264.4 yuan. Comparison of the mechanical and artificial models reveals that the average price of each ton of Keywords: Â 5 Straw fuel straw differs by 121 yuan. Under the assumption that the annual purchase amount of straw is 2 10 Â 7 Logistics system of straw collection, tons, the cost of 2.42 10 yuan per year can be saved. Thus, Laifa Straw Recycling Company of Henan storage and transportation Sheqi should consider the mechanical model. Sensitivity analysis of the two models shows that the Mathematical model collection cost is the most sensitive factor when the straw recycling company utilizes the artificial model Cost of straw collection, because most farmers go out to work, so a shortage in rural labor force occurs; this shortage results in storage and transportation increased cost of artificial collection. -

Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects)

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 34473-01 February 2006 PRC: Henan Wastewater Management and Water Supply Sector Project (11 Wastewater Management and Water Supply Subprojects) Prepared by Henan Provincial Government for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 02 February 2006) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.12 $1.00 = CNY8.06 The CNY exchange rate is determined by a floating exchange rate system. In this report a rate of $1.00 = CNY8.27 is used. ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD – biochemical oxygen demand COD – chemical oxygen demand CSC – construction supervision company DI – design institute EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMC – environmental management consultant EMP – environmental management plan EPB – environmental protection bureau GDP – gross domestic product HPG – Henan provincial government HPMO – Henan project management office HPEPB – Henan Provincial Environmental Protection Bureau HRB – Hai River Basin H2S – hydrogen sulfide IA – implementing agency LEPB – local environmental protection bureau N – nitrogen NH3 – ammonia O&G – oil and grease O&M – operation and maintenance P – phosphorus pH – factor of acidity PMO – project management office PM10 – particulate -

EIB-Funded Rare, High-Quality Timber Forest Sustainability Project Non

EIB-funded Rare, High-quality Timber Forest Sustainability Project Non-technical Summary of Environmental Impact Assessment State Forestry Administration December 2013 1 Contents 1、Source of contents ............................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2、Background information ................................................................... 1 3、Project objectives ................................................................................ 1 4、Project description ............................................................................. 1 4.1 Project site ...................................................................................... 1 4.2 Scope of project .............................................................................. 2 4.3 Project lifecyle .............................................................................. 2 4.4 Alternatives .................................................................................... 3 5、 Factors affecting environment ...................................................... 3 5.1 Positive environmental impacts of the project ............................ 3 5.2 Without-project environment impacts ........................................ 3 5.3 Potential negative envrionmnetal impacts ..................................... 3 5.4 Negative impact mitigation measures ............................................ 4 6、 Environmental monitoring .............................................................. 5 6.1 Environmental monitoring during project implementation .......... -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115