In 1965, at the Ripe Old Age of Seventeen, I Spent Some Time, Quite

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Count Down: Six Kids Vie for Glory at the World's Toughest Math

Count Down Six Kids Vie for Glory | at the World's TOUGHEST MATH COMPETITION STEVE OLSON author of MAPPING HUMAN HISTORY, National Book Award finalist $Z4- 00 ACH SUMMER SIX MATH WHIZZES selected from nearly a half million EAmerican teens compete against the world's best problem solvers at the Interna• tional Mathematical Olympiad. Steve Olson, whose Mapping Human History was a Na• tional Book Award finalist, follows the members of a U.S. team from their intense tryouts to the Olympiad's nail-biting final rounds to discover not only what drives these extraordinary kids but what makes them both unique and typical. In the process he provides fascinating insights into the creative process, human intelligence and learning, and the nature of genius. Brilliant, but defying all the math-nerd stereotypes, these athletes of the mind want to excel at whatever piques their cu• riosity, and they are curious about almost everything — music, games, politics, sports, literature. One team member is ardent about water polo and creative writing. An• other plays four musical instruments. For fun and entertainment during breaks, the Olympians invent games of mind-boggling difficulty. Though driven by the glory of winning this ultimate math contest, in many ways these kids are not so different from other teenagers, finding pure joy in indulging their personal passions. Beyond the Olympiad, Steve Olson sheds light on such questions as why Americans feel so queasy about math, why so few girls compete in the subject, and whether or not talent is innate. Inside the cavernous gym where the competition takes place, Count Down reveals a fascinating subculture and its engaging, driven inhabitants. -

Foundations of Computation, Version 2.3.2 (Summer 2011)

Foundations of Computation Second Edition (Version 2.3.2, Summer 2011) Carol Critchlow and David Eck Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Hobart and William Smith Colleges Geneva, New York 14456 ii c 2011, Carol Critchlow and David Eck. Foundations of Computation is a textbook for a one semester introductory course in theoretical computer science. It includes topics from discrete mathematics, automata the- ory, formal language theory, and the theory of computation, along with practical applications to computer science. It has no prerequisites other than a general familiarity with com- puter programming. Version 2.3, Summer 2010, was a minor update from Version 2.2, which was published in Fall 2006. Version 2.3.1 is an even smaller update of Version 2.3. Ver- sion 2.3.2 is identical to Version 2.3.1 except for a change in the license under which the book is released. This book can be redistributed in unmodified form, or in mod- ified form with proper attribution and under the same license as the original, for non-commercial uses only, as specified by the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 Li- cense. (See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/) This textbook is available for on-line use and for free download in PDF form at http://math.hws.edu/FoundationsOfComputation/ and it can be purchased in print form for the cost of reproduction plus shipping at http://www.lulu.com Contents Table of Contents iii 1 Logic and Proof 1 1.1 Propositional Logic ....................... 2 1.2 Boolean Algebra ....................... -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society Is Support, for Carrying out the Work of the Society

OTICES OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY 1989 Steele Prizes page 831 SEPTEMBER 1989, VOLUME 36, NUMBER 7 Providence, Rhode Island, USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences This calendar lists all meetings which have been approved prior to Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices the date this issue of Notices was sent to the press. The summer which contains the program of the meeting. Abstracts should be sub and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Associ mitted on special forms which are available in many departments of ation of America and the American Mathematical Society. The meet mathematics and from the headquarters office of the Society. Ab ing dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this stracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have been as at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on signed. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the below. First and supplementary announcements of the meetings will deadline for abstracts for consideration for presentation at special have appeared in earlier issues. sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For Abstracts of papers presented at a meeting of the Society are pub additional information, consult the meeting announcements and the lished in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American list of organizers of special sessions. -

Number Systems

Number Systems PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 09 Mar 2013 02:39:37 UTC Contents Articles Two's complement 1 Ones' complement 10 Binary-coded decimal 14 Gray code 24 Hexadecimal 39 Octal 50 Binary number 55 References Article Sources and Contributors 70 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 72 Article Licenses License 73 Two's complement 1 Two's complement Two's complement is a mathematical operation on binary numbers, as well as a binary signed number representation based on this operation. The two's complement of an N-bit number is defined as the complement with respect to 2N, in other words the result of subtracting the number from 2N. This is also equivalent to taking the ones' complement and then adding one, since the sum of a number and its ones' complement is all 1 bits. The two's complement of a number behaves like the negative of the original number in most arithmetic, and positive and negative numbers can coexist in a natural way. In two's-complement representation, negative numbers are represented by the two's complement of their absolute value;[1] in general, negation (reversing the sign) is performed by taking the two's complement. This system is the most common method of representing signed integers on computers.[2] An N-bit two's-complement numeral system can represent every integer in the range −(2N − 1) to +(2N − 1 − 1) while ones' complement can only represent integers in the range −(2N − 1 − 1) to +(2N − 1 − 1). -

Omega: Chaitin's Demon

From SIAM News, Volume 39, Number 1, January/February 2006 Omega: Chaitin’s Demon Meta Math!: The Quest for Omega. By Gregory Chaitin, Pantheon Books, New York, 2005, 240 pages, $26.00. Problem: Name a book that combines mathematical history, philosophy, more than a whiff of theology, personal palaver, and brilliant insights, along with evidence of a Borges-like imagination, eyebrow-raising mathematical constructions, breathtaking excitement, grandiose ruminations, and some bosh. Solution: The book under review. This solution may not be unique, but with the addition of a side condition—that the book be a guide for readers seeking to learn where the oracular mathematical demon Omega resides—we certainly have uniqueness. We live in an age when some of our most brilliant scientists and mathematicians want to go beyond the confines of their disciplines as cur- rently pursued and create something revolutionary: one super-transcendental step for mankind, something meta, and, with an eye on sales, something sensational. Some years ago Gregory Chaitin, one of the stars at the IBM T.J. BOOK REVIEW Watson Research Center, defined a real number (or, more precisely, a construction, because a specific number Ω By Philip J. Davis emerges only after a Turing machine and an encoding have been arbitrarily selected) that he dubbed . Definition: Ω is the probability that a random program on a universal Turing machine will halt under the probability distribu- tion that a program of length k has probability 2 –k. In its ambiguity, Ω is something like the god Jupiter—now a swan, now a bull, depending on the opportunities available. -

Complete Issue 22, 2000

Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal Issue 22 Article 18 4-1-2000 Complete Issue 22, 2000 Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmnj Recommended Citation (2000) "Complete Issue 22, 2000," Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal: Iss. 22, Article 18. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmnj/vol1/iss22/18 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 1 065-82 Humanistic Mathematics Network Journal Issue #22 April2000 STRUCTURAL SOCIO- LANGUAGE LINGUISTICS LINGUISTICS PEDAGOGY t '. ~ ~ MATHEMATICS __.. META- __.. MATHEMATICS MATHEMATICS EDUCATION In this issue... • What We Say, What Our Students Hear: A Case for Active Listening (p. 1) • Coherence in Theories Relating Mathematics and Language (p. 32) INVITATION TO AUTHORS EDITOR Essays, book reviews, syllabi, poetry, and letters are wel- Alvin White comed. Your essay should have a title, your name and ad- Harvey Mudd College dress, e-mail address, and a brief summary of content. In addition, your telephone number (not for publication) ASSOCIATE EDITORS would be helpful. Susan Addington If possible, avoid footnotes; put references and bibliogra- California State University, San Bernadino phy at the end of the text, using a consistent style. Please put all figures on separate sheets of paper at the end of the Stephen Brown text, with annotations as to where you would like them to State University of New York, Buffalo fit within the text; these should be original photographs, or drawn in dark ink. -

Part I: 1865-1898

MATHEMATICS AT CORNELL MATHEMATICS AT CORNELL: STORIES AND CHARACTERS, 1865—1965 PART I: 1865-1898 PART I: 1865—1898, THE FIRST THIRTY YEARS PREAMBLE CHAPTER I: BEFORE CORNELL, 1800—1867 I.1 THREE EUROPEAN SCIENTISTS I.2 SCIENCE AND EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES BEFORE 1870 I.3 THE FOUNDERS CHAPTER II: THE EARLY YEARS, 1868—1878 II.1 THE OPENING OF CORNELL II.2 THE DEPARTMENT OF E.W. EVANS, Z.H. POTTER AND H.T. EDDY II.3 THE DEPARTMENT OF J.E. OLIVER, G.W. JONES AND L.A. WAIT II.4 THE FIRST STUDENTS CHAPTER III: TRANSITION, 1879—1887 III.1 JAMES EDWARD OLIVER (ALMOST SACKED) III.2 ABRAM ROGER BULLIS (1854—1928) III.3 ARTHUR STAFFORD HATHAWAY (1858—1934) III.4 THE JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY III.5 TOWARDS A GRADUATE PROGRAM INTERMEZZO: ROLLIN ARTHUR HARRIS (1863—1918) CHAPTER IV: THE BIRTH OF THE GRADUATE PROGRAM, 1888—1898 IV.1 THE RISE OF A COMMUNITY IV.2 GÖTTINGEN AND THE MATHEMATICAL CLUB IV.3 THE DEATHS OF JAMES OLIVER AND ERNST RITTER IV.4 MATHEMATICS AND CORNELL’S FOUNDING IDEAS MATHEMATICS AT CORNELL The Ithaca Journal, January 1st 18281 Beneath our feet the village lies, Above, around, on either side Improvements greet us far and wide. Here Eddy’s factory appears, First of the hardy pioneers. Yes, Ithaca, where from this brow I gaze around upon you, now I see you not as first I knew. Your dwellings, humble, how and few, Your chimney smokes I then could count; But now my eyes cannot surmount The splendid walls that meet the eye And mock my early memory. -

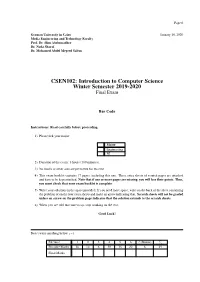

Final Exam 2019

Page 0 German University in Cairo January 18, 2020 Media Engineering and Technology Faculty Prof. Dr. Slim Abdennadher Dr. Nada Sharaf Dr. Mohamed Abdel Megeed Salem CSEN102: Introduction to Computer Science Winter Semester 2019-2020 Final Exam Bar Code Instructions: Read carefully before proceeding. 1) Please tick your major Major Engineering BI 2) Duration of the exam: 3 hours (180 minutes). 3) No books or other aids are permitted for this test. 4) This exam booklet contains 17 pages, including this one. Three extra sheets of scratch paper are attached and have to be kept attached. Note that if one or more pages are missing, you will lose their points. Thus, you must check that your exam booklet is complete. 5) Write your solutions in the space provided. If you need more space, write on the back of the sheet containing the problem or on the four extra sheets and make an arrow indicating that. Scratch sheets will not be graded unless an arrow on the problem page indicates that the solution extends to the scratch sheets. 6) When you are told that time is up, stop working on the test. Good Luck! Don’t write anything below ;-) Exercise 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 (Bonus) P Possible Marks 16 14 6 30 15 20 6 91 Final Marks CSEN102: Introduction to Computer Science, Final Exam, January 18, 2020 Page 1 Exercise 1 General arithmetics (3+5+4+4=16 Marks) Number conversions In this exercise you have to convert numbers from one base to another. A number n of a base b other than 10 will be given on this page as nb For decimal numbers, the subscript base can be omitted (i. -

Powers and Exponents Page Historylast Edited by Joe Redish 2 Years, 8 Months Ago Class Content >Modeling with Mathematics > Math Recap

Powers and exponents Page historylast edited by Joe Redish 2 years, 8 months ago Class content >Modeling with mathematics > Math recap In understanding how one variable depends on another, we introduced the idea of functional dependence. This helps us understand not just that one variable depends on another, but how it depends on the other. This is especially important in complex situations such as biology where many variables can be involved and "which one dominates" matters. Powers Some of the most useful and convenient functional dependencies that we will encounter are power laws. This means that the variable we choose to be dependent depends on the variable we choose to be independent by some power of that variable. Thus y = f (x ) = xN = x multiplied by itself N times says that "y goes like x raised to the Nth power". Exponentials We know that a quadratic function rises faster than a linear one (eventually) and a cubic rises faster than a quadratic. But there is an extremely useful function that eventually rises faster than any power. This is the exponential function. In this case, the variable is not raised to a power -- the variable itself is in the power that some constant is raised to. So as the variable gets bigger and bigger, the power the constant is raised to gets bigger and bigger. We write y = ex . Now e could be any constant, but we typically take it as a special transcendental number (that means it's decimal representation never stops and never repeats): e = 2.712... This particular choice is because when we make this choice, the function ex is its own derivative. -

New Mathematical Diversions

MARTIN GARDNER MARTIN GARDNER NEW MATHEMATICAL MATHEMATICALN~N RTIN GARDNER More a from Martin Gardner as they appeared in Scientific American with a Postscript and new Bibliography from the Author and over 100 drawings and diagrams The Mathematical Association of America Washington, D.C. @ 1995 by The Mathematical Association of America (Incorporated) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 95-76293 ISBN 0-88385-517-8 Printed in the United States of America Current Printing (last digit): lo987654321 SPECTRUM SERIES Published by THE MATHEMATICAL ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Committee on Publications JAMES W. DANIEL, Chair Spectrum Editorial Board ROGER HORN, Editor ARTHUR T. BENJAMIN DIPA CHOUDHURY HUGH M. EDGAR RICHARD K. GW DAN KALMAN LESTER H. LANGE MARY R. PARKER A. WAYNE ROBERTS EDWARD R. SCHEINERMAN SANFORD SEGAL SPECTRUM SERIES The Spectrum Series of the Mathematical Association of America was so named to reflect its purpose: to publish a broad range of books including biographies, accessible expositions of old or new rnathe- matical ideas, reprints and revisions of excellent out-of-print books, popular works, and other monographs of high interest that will appeal to a broad range of readers, including students and teachers of mathematics, mathematical amateurs, and researchers. All the Math That's Fit to Print, by Keith Devlin Complex Numbers and Geometry, by Liang-shin Hahn Cryptology, by Albrecht Beutelspacher From Zero to Infinity, by Constance Reid I Want to be a Mathematician, by Paul R. Halmos Journey into Geometries, by Marta Sved The Last Problem, by E. T. Bell (revised and updated by Underwood Dudley) The Lighter Side of Mathematics: Proceedings of the Eug2ne Strens Memorial Conference on Recreational Mathematics & its History, edited by Richard K. -

Problem Books in Mathematics

Problem Books in Mathematics Edited by P. Winkler Problem Books in Mathematics Series Editor: Peter Winkler Pell’s Equation by Edward J. Barbeau Polynomials by Edward J. Barbeau Problems in Geometry by Marcel Berger, Pierre Pansu, Jean-Pic Berry, and Xavier Saint-Raymond Problem Book for First Year Calculus by George W. Bluman Exercises in Probability by T. Cacoullos Probability Through Problems by Marek Capin´ski and Tomasz Zastawniak An Introduction to Hilbert Space and Quantum Logic by David W. Cohen Unsolved Problems in Geometry by Hallard T. Croft, Kenneth J. Falconer, and Richard K. Guy Berkeley Problems in Mathematics, (Third Edition) by Paulo Ney de Souza and Jorge-Nuno Silva The IMO Compendium: A Collection of Problems Suggested for the International Mathematical Olympiads: 1959-2004 by Dusˇan Djukic´, Vladimir Z. Jankovic´, Ivan Matic´, and Nikola Petrovic´ Problem-Solving Strategies by Arthur Engel Problems in Analysis by Bernard R. Gelbaum Problems in Real and Complex Analysis by Bernard R. Gelbaum (continued after index) Christopher G. Small Functional Equations and How to Solve Them Christopher G. Small Department of Statistics & Actuarial Science University of Waterloo 200 University Avenue West Waterloo N2L 3G1 Canada [email protected] Series Editor: Peter Winkler Department of Mathematics Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 03755 USA [email protected] ISBN-13: 978-0-387-34539-0 e-ISBN-13: 978-0-387-48901-8 Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 39-xx Library of Congress Control Number: 2006929872 © 2007 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for with reviews or scholarly analysis. -

Small Is Beautiful” – Mathematical Modelling and Free Surface Flows

Chapter 3 Where “Small is Beautiful” – Mathematical Modelling and Free Surface Flows John D. Fenton Abstract Mathematical and computational models in river and canal hydraulics of- ten require data that may not be available, or it might be available and accurate while other information is only roughly known. There is considerable room for the development of approximate models requiring fewer details but giving more insight. Techniques are presented, especially linearisation, which is used in several places. A selection of helpful mathematical methods is presented. The approximation of data is discussed and methods presented, showing that a slightly more sophisticated approach is necessary. Several problems in waves and flows in open channels are then examined. Complicated methods have often been used instead of standard sim- ple numerical ones. The one-dimensional long wave equations are discussed and presented. A formulation in terms of cross-sectional area is shown to have a surpris- ing property, that the equations can be solved with little knowledge of the stream bathymetry. Generalised finite difference methods for long wave equations are pre- sented and used. They have long been incorrectly believed to be unstable, which has stunted development in the field. Past presentations of boundary conditions have been unsatisfactory, and a systematic exposition is given using finite differences. The nature of the long wave equations and their solutions is examined. A simplified but accurate equation for flood routing is presented. However, numerical solution of the long wave equations by explicit finite differences is also simple, and more gen- eral. A common problem, the numerical solution of steady flows is then discussed.