A Burma River Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) Buddhism Is an Integral Part of Burmese Culture

Burmese Buddhist Imagery of the Early Bagan Period (1044 – 1113) 2 Volumes By Charlotte Kendrick Galloway A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University November 2006 ii Declaration I declare that to the best of my knowledge, unless where cited, this thesis is my own original work. Signed: Date: Charlotte Kendrick Galloway iii Acknowledgments There are a number of people whose assistance, advice and general support, has enabled me to complete my research: Dr Alexandra Green, Dr Bob Hudson, Dr Pamela Gutman, Dick Richards, Dr Tilman Frasch, Sylvia Fraser- Lu, Dr Royce Wiles, Dr Don Stadtner, Dr Catherine Raymond, Prof Michael Greenhalgh, Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi, U Aung Kyaing, Dr Than Tun, Sao Htun Hmat Win, U Sai Aung Tun and Dr Thant Thaw Kaung. I thank them all, whether for their direct assistance in matters relating to Burma, for their ability to inspire me, or for simply providing encouragement. I thank my colleagues, past and present, at the National Gallery of Australia and staff at ANU who have also provided support during my thesis candidature, in particular: Ben Divall, Carol Cains, Christine Dixon, Jane Kinsman, Mark Henshaw, Lyn Conybeare, Margaret Brown and Chaitanya Sambrani. I give special mention to U Thaw Kaung, whose personal generosity and encouragement of those of us worldwide who express a keen interest in the study of Burma's rich cultural history, has ensured that I was able to achieve my own personal goals. There is no doubt that without his assistance and interest in my work, my ability to undertake the research required would have been severely compromised – thank you. -

4D3N Mandalay, Mahamuni Pagoda, Amarapura, Mingun Bell, Pyin Oo

Cultural & Heritage *4D3N Mandalay, Mahamuni Pagoda, Amarapura, Mingun Bell, Pyin Oo Lwin Highland, U Bein Bridge* Greatest Values of All • Maha Ant Htoo Kan Thar Pagoda • Pyin Oo Lwin Highland • 3-nights stay in Mandalay • Amarapura Discovery Tour • Mandalay Palace Discovery Tour • 19th century Shwenandaw Monastery • Kandawgyi Botanical Garden • Boat cruise to explore Mingun Stupa • Admire the sunset at Mandalay Hill Shwenandaw Monastery Itinerary Day 1 Discover the 18th century Mandalay Palace (L/D) Arrive at Mandalay International Airport Meet & greet by tour guide at the airport’s arrival gate Enjoy Lunch at Local Restaurant Discover the 18th century Mandalay Palace, the Royal Palace of the last Burmese monarchy Marvel at the 19th century Shwenandaw Monastery, famous for its exquisite woodcarving and architecture Admire the sunset at Mandalay Hill, overlooking Mandalay Palace Enjoy Dinner at Local Restaurant Check in hotel in Mandalay for 3-nights Day 2 Explore the Ancient Ruins of Mingun Pahtodawgyi (B/L/D) Travel to Amarapura, Myanmar’s former capital, 1h0m, 22km Selfie-photography at the 200 year-old U Bein Bridge, believe to be the world’s oldest & longest teakwood bridge Visit Mahagandhayon Monastery in Amarapura, Myanmar’s most prominent monastic college Enjoy Lunch at Local Restaurant Take an hour boat cruise along Irrawaddy River to Mingun Town,where the world largest ringing bell exist. During the boat journey, you will see life along the river, fishing villages, market boats, women attending to their washing, and children -

The Making of Modern Burma Thant Myint-U Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521780217 - The Making of Modern Burma Thant Myint-U Index More information Index Abhisha Husseini, 51 and local rebellions, 172, 173–4, 176 Afghanistan, 8, 22, 98, 102, 162 and modern Burma, 254 agriculture, 36, 37, 40, 44, 47, 119, 120, payment of, 121 122, 167, 224, 225, 236, 239; see also reforms, 111–12 cultivators Assam, 2, 13, 15–16, 18, 19, 20, 95, 98, 99, Ahom dynasty, 15–16 220 Aitchison, Sir Charles, 190–1 athi, 33, 35 Alaungpaya, King, 13, 17, 58, 59–60, 61, Ava (city), 17, 25, 46, 53, 54 70, 81, 83, 90, 91, 107 population, 26, 54, 55 Alaungpaya dynasty, 59, 63, 161 Ava kingdom, 2 allodial land, 40, 41 administration, 28–9, 35–8, 40, 53–4, Alon, 26, 39, 68, 155, 173, 175 56–7, 62, 65–8, 69, 75–8, 108–9, Amarapura, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21, 26, 51, 53, 115–18, 158–60, 165–6 54, 119, 127, 149 anti-British attitudes, 6–7, 99, 101–3 rice prices, 143 and Bengal, 94, 95, 96, 98, 99–100 royal library, 96 boundaries of, 9, 12, 24–5, 92, 101, Amarapura, Myowun of, 104–5 220 Amherst, Lord, 106 British attitudes to, 6, 8–9, 120, 217–18, Amyint, 36, 38, 175 242, 246, 252 An Tu (U), 242 and Buddhism, 73–4, 94, 95, 96, 97, 108, Anglo-Burmese wars, 2, 79 148–52, 170–1 First (1824–6), 18–20, 25, 99, 220 ceremonies, 97, 149, 150 Second (1852–3), 23, 104, 126 and China, 47–8, 137, 138, 141, 142, Third (1885), 172, 176, 189, 191–3 143, 144, 147–8 animal welfare, 149, 171 chronicles of, 79–83, 86, 240 appanages, 29, 53, 61–3, 68, 69, 72–3, 77, and colonial state, 219–20 107, 108, 231 commercial concessions, 136–7 reform of, -

5) Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Shinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle 2.Pmd

Bayinnaung in the Hanthawadi Hsinbyumya Shin Ayedawbon Chronicle by Thaw Kaung King Bayinnaung (AD 1551-1581) is known and respected in Myanmar as a great war- rior king of renown. Bayinnaung refers to himself in the only inscription that he left as “the Conqueror of the Ten Directions”.1 but this epithet is not found in the main Myanmar chronicles or in the Ayedawbon texts. Professor D. G. E. Hall of Rangoon University wrote that “Bayinnaung was a born leader of men. the greatest ever produced by Burma. ”2 There is a separate Ayedawbon historical chronicle devoted specifically to the campaigns and achievements of Bayinnaung entitled Hsinbyumya-shin Ayedawbon.3 Ayedawbon The term Ayedawbon means “a historical account of a royal campaign” 4 It also means a chronicle which records the campaigns and achivements of great kings like Rajadirit, Bayinnaung and Alaungphaya. The Ayedawbon is a Myanmar historical text which records : (1) How great men of prowess like Bayinnaung consolidated their power and became king. (2) How these kings retained their power by military campaigns, diplomacy, alliances and 1. For the full text of The Bell Inscription of King Bayinnaung see Report of the Superintendent, Archaeological Survey, Burma . 1953. Published 1955. p. 17-18. For the English translations by Dr. Than Tun and U Sein Myint see Myanmar Historical Research Journal. no. 8 (Dec. 2001) p. 16-20, 23-27. 2. D. G. E. Hall. Burma. 2nd ed. London : Hutchinson’s University Library, 1956. p.41. 3. The variant titles are Hsinbyushin Ayedawbon and Hanthawadi Ayedawbon. 4. Myanmar - English Dictionary. -

Appendix to Atula Hsayadaw Shin Yasa: a Critical Biography of An

Appendix to Atula Hsayadaw Shin Yasa: a Critical Biography of an Eighteenth‐Century Burmese Monk: Documents related to Atula’s trial in 1784 (version 1.1) Alexey Kirichenko This appendix contains documents that detail the progress of Atula’s trial in 1784 or that were, in my analysis, relevant to it. The original Burmese text of each document is reproduced followed by either a translation or a summary of a document. I also provide comments that explain the contents and the purpose of the document in question. All documents are in chronological order and numbered sequentially. The references in the biography follow these numbers. In reproducing Burmese texts, the original spelling of the manuscripts or the source publications was provisionally retained (with few corrections). In later versions of this appendix I plan to edit the documents in accordance with modern Burmese spelling conventions. The summaries detail the key messages of documents simplifying the style and omitting the quotes from Buddhist texts and some minor points. In future versions the summaries will be replaced by full translations. Document no. 1 Royal order dated the eight day of the waning moon of Nayon 1144 (June 3, 1782) Text: /bkefawmfBuD;jrwfawmfrlvSaom omoem'g,umawmf b0&Sifrifw&m;BuD; trdefUawmf&Sdonf? t&yf&yf q&mawmfoCFmawmftaygifwdkU/ avtoacsFESifh urÇmwodef; yg&rDq,fyg; tjym;oHk;q,fudk jznfhawmfrlí oyÜnKtjzpfodkU a&mufawmfrlaom bk&m;jrwfpGm y&dedAÁmef,lawmfrlonfaemuf ykxkZOf&[ef;wdkU toD;oD; t,l0g' uGJjym;usifhaqmifMuonf/ tZmwowf umvmaomu oD&d"r®maomurifwdkUudk -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District, Nonthaburi Province, Thailand During Thonburi and Rattanakosin Periods (1767-1932)

MON BUDDHIST ARCHITECTURE IN PAKKRET DISTRICT, NONTHABURI PROVINCE, THAILAND DURING THONBURI AND RATTANAKOSIN PERIODS (1767-1932) Jirada Praebaisri* and Koompong Noobanjong Department of Industrial Education, Faculty of Industrial Education and Technology, King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Bangkok 10520, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: October 3, 2018; Revised: February 22, 2019; Accepted: April 17, 2019 Abstract This research examines the characteristics of Mon Buddhist architecture during Thonburi and Rattanakosin periods (1767-1932) in Pakkret district. In conjunction with the oral histories acquired from the local residents, the study incorporates inquiries on historical narratives and documents, together with photographic and illustrative materials obtained from physical surveys of thirty religious structures for data collection. The textual investigations indicate that Mon people migrated to the Siamese kingdom of Ayutthaya in large number during the 18th century, and established their settlements in and around Pakkret area. Located northwest of the present day Bangkok in Nonthaburi province, Pakkret developed into an important community of the Mon diasporas, possessing a well-organized local administration that contributed to its economic prosperity. Although the Mons was assimilated into the Siamese political structure, they were able to preserve most of their traditions and customs. At the same time, the productions of their cultural artifacts encompassed many Thai elements as well, as evident from Mon Buddhist temples and monasteries in Pakkret. The stylistic analyses of these structures further reveal the following findings. First, their designs were determined by four groups of patrons: Mon laypersons, elite Mons, Thai Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies Vol.19(1): 30-58, 2019 Mon Buddhist Architecture in Pakkret District Praebaisri, J. -

Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao

ICS TRAVEL GROUP is one of the first international DMCs to open own offices in our destinations and has since become a market leader throughout the Mekong region, Indonesia and India. As such, we can offer you the following advantages: Global Network. Rapid Response. With a centralised reservations centre/head All quotation and booking requests are answered office in Bangkok and 7 sales offices. promptly and accurately, with no exceptions. Local Knowledge and Network. Innovative Online Booking Engine. We have operations offices on the ground at every Our booking and feedback systems are unrivalled major destination – making us your incountry expert in the industry. for your every need. Creative MICE team. Quality Experience. Our team of experienced travel professionals in Our goal is to provide a seamless travel experience each country is accustomed to handling multi- for your clients. national incentives. Competitive Hotel Rates. International Standards / Financial Stability We have contract rates with over 1000 hotels and All our operational offices are fully licensed pride ourselves on having the most attractive pricing and financially stable. All guides and drivers are strategies in the region. thoroughly trained and licensed. Full Range of Services and Products. Wherever your clients want to go and whatever they want to do, we can do it. Our portfolio includes the complete range of prod- ucts for leisure and niche travellers alike. ICS TRAVEL ICSGROUPTRAVEL GROUP Contents Introduction 3 Tours 4 Cruises 20 Hotels 24 Yangon 24 Mandalay 30 Bagan 34 Mount Popa 37 Inle Lake 38 Nyaung Shwe 41 Ngapali 42 Pyay 45 Mrauk U 45 Ngwe Saung 46 Excursions 48 Hotel Symbol: ICS Preferred Hotel Style Hotel Boutique Hotel Myanmar | Content | 1 Putao Lahe INDIA INDIA Myitkyina CHINA CHINA Bhamo Muse MYANMAR Mogok Lashio Hsipaw BANGLADESHBANGLADESH Mandalay Monywa ICS TRA VEL GR OUP Meng La Nyaung Oo Kengtung Mt. -

Buddhism in Myanmar a Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1

Buddhism in Myanmar A Short History by Roger Bischoff © 1996 Contents Preface 1. Earliest Contacts with Buddhism 2. Buddhism in the Mon and Pyu Kingdoms 3. Theravada Buddhism Comes to Pagan 4. Pagan: Flowering and Decline 5. Shan Rule 6. The Myanmar Build an Empire 7. The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries Notes Bibliography Preface Myanmar, or Burma as the nation has been known throughout history, is one of the major countries following Theravada Buddhism. In recent years Myanmar has attained special eminence as the host for the Sixth Buddhist Council, held in Yangon (Rangoon) between 1954 and 1956, and as the source from which two of the major systems of Vipassana meditation have emanated out into the greater world: the tradition springing from the Venerable Mahasi Sayadaw of Thathana Yeiktha and that springing from Sayagyi U Ba Khin of the International Meditation Centre. This booklet is intended to offer a short history of Buddhism in Myanmar from its origins through the country's loss of independence to Great Britain in the late nineteenth century. I have not dealt with more recent history as this has already been well documented. To write an account of the development of a religion in any country is a delicate and demanding undertaking and one will never be quite satisfied with the result. This booklet does not pretend to be an academic work shedding new light on the subject. It is designed, rather, to provide the interested non-academic reader with a brief overview of the subject. The booklet has been written for the Buddhist Publication Society to complete its series of Wheel titles on the history of the Sasana in the main Theravada Buddhist countries. -

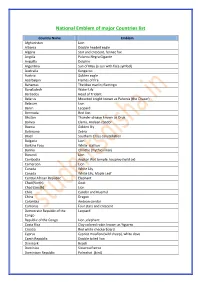

National Emblem of Major Countries List

National Emblem of major Countries list Country Name Emblem Afghanistan Lion Albania Double headed eagle Algeria Star and crescent, fennec fox Angola Palanca Negra Gigante Anguilla Dolphin Argentina Sun of May (a sun with face symbol) Australia Kangaroo Austria Golden eagle Azerbaijan Flames of fire Bahamas The blue marlin; flamingo Bangladesh Water Lily Barbados Head of Trident Belarus Mounted knight known as Pahonia (the Chaser) Belgium Lion Benin Leopard Bermuda Red lion Bhutan Thunder dragon known as Druk Bolivia Llama, Andean condor Bosnia Golden lily Botswana Zebra Brazil Southern Cross constellation Bulgaria Lion Burkina Faso White stallion Burma Chinthe (mythical lion) Burundi Lion Cambodia Angkor Wat temple, kouprey (wild ox) Cameroon Lion Canada White Lily Canada White Lily, Maple Leaf Central African Republic Elephant Chad(North) Goat Chad (South) Lion Chile Candor and Huemul China Dragon Colombia Andean condor Comoros Four stars and crescent Democratic Republic of the Leopard Congo Republic of the Congo Lion ,elephant Costa Rica Clay colored robin known as Yiguirro Croatia Red white checkerboard Cyprus Cypriot mouflon (wild sheep), white dove Czech Republic Double tailed lion Denmark Beach Dominica Sisserou Parrot Dominican Republic Palmchat (bird) Ecuador Andean condor Egypt Golden eagle Equatorial Guinea Silk cotton tree Eritrea Camel Estonia Barn swallow, cornflower Ethiopia Abyssinian lion European Union A circle of 12 stars Finland Lion France Lily Gabon Black panther Gambia Lion Georgia Saint George, lion Germany Corn -

Ageless Cities of Time

AGELESS CITIES OF TIME 1 INTRODUCTION The ancient cities in Myanmar are a wonder to behold as they still retain their striking beauty of timeless buildings, despite being worn by age and time. Several iconic landmarks present in these cities hold historical value that tells a story of the rise and fall of the kingdom, the glory of a capital, and the spread of Theravada Buddhism within the nation. You will discover much in these cities; from temples erected thousands of years ago, a township with excavated archaeological sites, and the prominence of Myanmar’s changing capitals, this is a land with an exciting history to tell. You’ll be taken in wonder as you visit all of Myanmar’s ancient civilisations and learn how the origins and history that led to the developing nation we see today. 2 PYU CITIES The Pyu Cities comprise of Halin, Beikthano and Sri Kestra. These sites have been excavated and are part of the Pyu Kingdom, which stretched from Tagaung in the north to the Ayeyarwady River and to south of present-day Daw. History During 832CE, the Pyu kingdom was attacked by an army of Nanzhao who kidnapped 3,000 citizens and took them away. The remaining citizens left behind went on to blend with the rest of Bamar society, which settled along the upper Ayeyarwady banks by the end of 800CE. Highlights Sri Kestra was excavated in 1926 and there was relic chambers that were discovered to hold a twenty-page Buddhist manuscript and gilded Buddha images. There were also three pagodas: Payama, Payagyi and Bawbawgyi that points to Sri Kestra being a centre for early Buddhism in Myanmar. -

Neil Sowards

NEIL SOWARDS c 1 LIFE IN BURMA © Neil Sowards 2009 548 Home Avenue Fort Wayne, IN 46807-1606 (260) 745-3658 Illustrations by Mehm Than Oo 2 NEIL SOWARDS Dedicated to the wonderful people of Burma who have suffered for so many years of exploitation and oppression from their own leaders. While the United Nations and the nations of the world have made progress in protecting people from aggressive neighbors, much remains to be done to protect people from their own leaders. 3 LIFE IN BURMA 4 NEIL SOWARDS Contents Foreword 1. First Day at the Bazaar ........................................................................................................................ 9 2. The Water Festival ............................................................................................................................. 12 3. The Union Day Flag .......................................................................................................................... 17 4. Tasty Tagyis ......................................................................................................................................... 21 5. Water Cress ......................................................................................................................................... 24 6. Demonetization .................................................................................................................................. 26 7. Thanakha ............................................................................................................................................