The Avon Valley Copper and Brass Industry Bristol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keynsham Report

AVON EXTENSIVE URBAN SURVEY ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT REPORT KEYNSHAM DECEMBER 1999 AVON EXTENSIVE URBAN AREAS SURVEY - KEYNSHAM ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by Emily La Trobe-Bateman. I would like to thank the following people for their help and support: Vince Russett, project manager (Avon County Archaeologist subsequently North Somerset Archaeologist) and Dave Evans (Avon Sites and Monuments Officer, subsequently South Gloucestershire Archaeologist) for their comments on the draft report; Pete Rooney and Tim Twiggs for their IT support, help with printing and advice setting up the Geographical Information System (GIS) database; Bob Sydes (Bath and North East Somerset Archaeologist), who managed the final stages of the project; Nick Corcos for making the preliminary results of his research available and for his comments on the draft report; Lee Prosser for kindly lending me a copy of his Ph.D.; David Bromwich for his help locating references; John Brett for his help locating evaluations carried out in Keynsham.. Special thanks go to Roger Thomas, Graham Fairclough and John Scofield of English Heritage who have been very supportive throughout the life of the project. Final thanks go to English Heritage whose substantive financial contribution made the project possible. BATH AND NORTH EAST SOMERSET COUNCIL AVON EXTENSIVE URBAN AREAS SURVEY - KEYNSHAM CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The aims of the report 1 1.2 Major sources of evidence 1 1.3 A brief history of Keynsham 3 2.0 Prehistoric archaeology (pre-AD 47) 8 2.1 Sources -

Avon Archaeology

1 l ~~iro~ AVON ARCHAEOLOGY \ '' ~\(i;--.. j I \ -:_1 c~ r" ,-.-..ii. '\~-- ~ ' Volume 6 BRISTOLAND AVONARCHAEOLOGY 6 1987 CONTENTS Address by L.V. Grinsell on the occasion of the 25th Anniversa!Y of B(A)ARG 2 L.V. Grinsell Bibliography 1972-1988 3 compiled by N. Thomas Domesday Keynsham - a retrospective examination of an old English Royal Estate 5 M. Whittock Excavations in Bristol in 1985-86 11 R. Burchill, M. Coxah, A. Nicholson & M. W. Ponsford The Lesser Cloister and a medieval drain at St. Augustine's Abbey, Bristol 31 E.J. Boore Common types of earthenware found in the Bristol area 35 G.L. Good & V.E.J. Russett Avon Archaeology 1986 and 1987 44 R. Iles & A. Kidd A Bi-facial polished-edge flint knife from Compton Dando 57 Alan Saville Excavations at Burwalls House, Bristol, 1980 58 N.M. Watson Cromhall Romano-British villa 60 Peter Ellis An Anglo-Saxon strap-end from Winterbourne, Bristol 62 J. Stewart Eden rediscovered at Twerton, Bath 63 Mike Chapman St. John's Keynsham - results of excavation, 1979 64 Peter Ellis An 18th-19th century Limekiln at Water Lane, Temple, Bristol 66 G.L. Good Medieval floor tiles from Winterbrmrne 70 J.M. Hunt & J.R. Russell Book reviews 72 (c) Authors and Bristol & Avon Archaeological Research Group COMMITTEE 1987-88 Chairman N. Thomas Vice-Chairman A.J. Parker Secretary J. Bryant Treasurer J. Russell Membership Secretary A. Buchan Associates Secretary G. Dawson Fieldwork Advisor M. Ponsford Editor, Special Publications R. Williams Publicity Officer F. Moor Editor, BAA R. -

Issue-371.Pdf

The Week in East Bristol & North East Somerset FREE Issue no 371 14th May 2015 Read by over 30,000 people every week In this week’s issue ...... pages 6 & 19 Election shocks across the region . Parliamentary and local government results page 5 Final journey for railway enthusiast . Tribute to Bob Hutchings MBE page 22 Temporary home for Lyde Green Primary . New school will spend first year at Downend in 2 The Week • Thursday 14th May 2015 Well, a week ago we wrote that nobody seemed to have any Electionreal idea of how the General Election would turn out,shockwave and in the end, neither winners, losers nor commentators came anywhere close to predicting the result. In the Parliamentary constituencies we cover, we have seen marginal seats become safe Conservative seats and a Liberal Democrat minister lose his job. UKIP and the Green Party went from 'wasted votes' to significant minority parties. Locally, two councils which have had no overall control for the last eight years are now firmly in the hands of Conservative councillors while Bristol, which elects a third of its council on an annual The count at Bath University basis, remains a hung administration. The vote for its elected mayor takes place next year. You can read all about the constituency and local government Dawn was breaking over Bath and Warmley where The Week elections last week on pages 6 & 19. In was present at the counts for the North East Somerset and Our cover picture shows Clemmie, daughter of Kingswood MP Kingswood constituencies, before we knew that both sitting Chris Skidmore at last week's vote. -

Coorspttng Ptiorp

COorspttng Ptiorp. BY THE HEY. E. W. WEAVER, M.A., F.S.A. rr^HE Priorj of Worspring was founded by William de Courteney ; the exact date of the foundation is not known. The letter from the founder to Bishop Joscelyn is not dated, but in it the Bishop is called Bishop of Bath, which title seems to refer to the years between 1219 and 1242;^ at any rate it was a going concern in 1243, for in that year Prior Reginald died and Prior Richard succeeded him. It was dedi- cated to the B.y.M. and St. Thomas of Canterbury, and was a house of Canons Regular of the Rule of St. Augustine and of the Order of St. Victor. The letter of the founder to the Bishop points to the great monastery of the same order at Bristol as a kind of foster- mother to Worspring. Some of the Augustinian Monasteries were of the Rule of St. Victor : St. Augustine’s Abbey at Bristol, Keynsham Abbey, Stavordale Priory and Worspring Priory in Somerset, and Wormesley Priory in Herefordshire were all of this Rule. The Rule was named after the famous Abbey of St. Victor in Paris, which was founded by Louis VI in 1129. Gregory Rivius, in his Monastica Historia (Lipsiae, 1737, cap. 10, p. 26), gives a list of rules of the Canons Regular of St. Victor, and shews how their rule differed from that of St. Augustine. We ])rint below an Inspeximus taken from the Bath Cartu- lary (S.R.S., ^AI, ii, 58). In a note (260?i) the Rev. -

Warnings As Boy Falls Seriously Ill After Swimming at Saltford

THE WEEK IN East Bristol & North East Somerset FREE Issue 534 18th July 2018 Read by over 40,000 people each week Warnings as boy falls seriously ill after swimming at Saltford With schools breaking up after a young boy from Rio Smith’s mum Shelley improving after picking up this week, young people in Warmley who swam at said her son, a pupil at the a bug from the water particular are being urged Saltford fell dangerously Sir Bernard Academy in which led to him being put to heed river safety advice ill. Oldland Common, is in insolation at Bristol Children’s Hospital. She said: “Rio has been very ill with a bug he picked up from the river at Saltford. It caused diarrhoea, vomiting, severe dehydration that caused his heart rate to double, resulting in him collapsing.” Continued on page 3 2 The Week in • Wednesday 18th July 2018 Warnings as boy falls seriously ill after swimming at Saltford Continued from page 1 We wish him a speedy schools and other schools Writing on Facebook she recovery from the illness, within our trust were also urged people to share his which it is suspected is a made aware of the boy’s story, while the mother of result of swimming in the illness so that they could 14-year-old Aaron Burgess, river at Saltford. take similar action. who drowned at Saltford "We have spoken to all our "At SBL, we had already Weir six years ago, also students about the health done some work on river issued an emotional and safety risks associated safety with students in message. -

Past Present

( NORTH WANSDYKE PAST AND PRESENT 0 0 Keynsham & Saltford Local History Society No. 4, 1992 North Wansdyke Past and Present Journal of Keynsham & Saltford Local History Society Editor: Charles Browne 30 Walden Road, Keynsham, Bristol BS 18 1QW Telephone: Bristol (0272) 863116 Contents Stanton Prior, by B. J. Lowe & E. White 3 The Doctors Harrison, by Sue Trude 13 Memories ofKeynsham, by William Sherer 15 Postscript to 'The Good(?) Old Days', by Margaret Whitehead 18 Tales My Father Told Me, by Dick Russell 19 Demolition Discoveries, by Barbara J. Lowe 25 Roman Remains at Somerdale, by Charles Browne 26 Published by Keynsham & Saltford Local History Society No. 4, 1992 Copyright() 1992: the individual authors and Keynsham & Saltford Local History Society. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers and copyright holders. 2 Stanton Prior Barbara J. Lowe & Elizabeth White Part 1 The village nestles in a hollow bounded by an east-west road on the southern ridge, and on the north by two major earthworks: the Iron Age Stantonbury Hillfort and Wansdyke earthwork of possible Dark Age date. Land has probably been worked here since late Neolithic times. Evidence in the form of a flint blade (probably once accompanying a late Neolithic burial), sherds ofBronze Age beaker ware (c.1750 BC) and Roman pottery sherds and other artefacts indicate continuity of occupation. The village boundaries of Stanton Prior, Corston and Marksbury, all converge on Stantonbury, but ignore Wansdyke, the other great archaeo logical feature here. -

Park and Gardens Designations (PDF)

Bath and North East Somerset Council Designation Full Report 07/02/2012 Number of records: 86 DesigUID: DBN3643 Type: Registered Park or Garden Status: Active Preferred Ref NHLE UID Other Ref Name: 19 Sion Hill (Local) Grade: Date Assigned Amended: Revoked: Legal Description Small town garden, thought to be unaltered since C18 creation; certainly little changed since OS 1st edition; mixture of decorative and kitchen planting. Curatorial Notes Designating Organisation: Location Grid Reference: Centroid ST 7399 6607 (MBR: 34m by 53m) Map sheet: ST76NW Area (Ha): 0.10 Administrative Areas Civil Parish Bath, Bath & North East Somerset Postal Addresses - None recorded Sources Monograph: Harding S & Lambert D. 1991. A Gazetteer of Historic Parks and Gardens in Avon. p12 Associated Monuments MBN10089 Ornamental Park: Garden Additional Information DesigUID: DBN3626 Type: Registered Park or Garden Status: Active Preferred Ref NHLE UID Other Ref Name: 4 Cleveland Place West (Local) Grade: Date Assigned Amended: Revoked: Legal Description Eccentric grass-terraced garden originally created c1870-1910, by William Sweetland, behind his organ factory and running down to the River Avon. The garden featured several stone ornaments; stone coffin; Ionic column from demolished St Mary’s Chapel, Queen Square; urn scratch carved with organ motifs. Mature cedar and Wellingtonia by north wall. Part owned by City Council and leased to Bath Canoe Club. Curatorial Notes GIS polygon estimated only. Designating Organisation: Location Grid Reference: Centroid ST 7529 6566 (MBR: 42m by 49m) Map sheet: ST76NE Area (Ha): 0.10 Administrative Areas Civil Parish Bath, Bath & North East Somerset Postal Addresses - None recorded Sources DesignationFullRpt Report generated by HBSMR from exeGesIS SDM Ltd Page 1 DesigUID: DBN3626 Name: 4 Cleveland Place West (Local) Monograph: Harding S & Lambert D. -

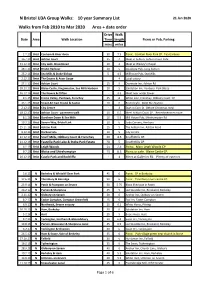

N Bristol U3A Group Walks: 10 Year Summary List

N Bristol U3A Group Walks: 10 year Summary List 21 Jan 2020 Walks from Feb 2010 to Mar 2020 Area + date order Drive Walk Date Area Walk Location Time length Picnic or Pub, Parking mins miles 2.7.10 Brist Conham & River Avon 30 7.5 Picnic. Conham River Park CP. Tea Gardens 16.7.10 Brist Ashton Court 15 4 Meet in Ashton. Ashton Court Cafe 31.12.10 Brist City walk -Broadmead 10 2 Meet at Wesley's Chapel 28.1.11 Brist Bristol Harbour 10 5 Dovecote Pub, Long Ashton 25.2.11 Brist Sea Mills & Stoke Bishop 5 4.5 Millhouse Pub, Sea Mills 2.12.11 Brist The Downs & Avon Gorge - 4 Local eatery 27.1.12 Brist Ashton Court 15 5 Dovecote Inn, Ashton Rd 28.12.12 Brist Blaise Castle, Kingsweston, Sea Mills Harbour 10 5 Salutation Inn, Henbury. Park Blaise 26.12.14 Brist The Downs & Clifton - 3.5 Meet near water tower. 9.1.15 Brist Frome Valley, Purdown, Frenchay 25 8 White Lion, Frenchay. Oldbury Court CP 23.1.15 Brist Street Art East Bristol & Easton 10 6 Bristol Cafe. Meet Bus Station 2.12.15 Brist City Centre - 4 Start in Corn St. Before Christmas meal 18.12.15 Brist Ashton Court - pavement walk 10 6.5 Meet Ashton Court CP. Refreshments en route 8.1.16 Brist Durdham Down & Sea Mills 10 5.5 Mill House Pub, Shirehampton Rd 19.2.16 Brist Severn Way, Bristol Link 20 6 Toby Carvery, Henbury 25.11.16 Brist Ashton Park 15 5 The Ashton Inn, Ashton Road 9.12.16 Brist Harbourside 10 5 City Centre 22.12.17 Brist Snuff Mills, Oldbury Court & Frenchay 20 4.5 Snuff Mills CP. -

Saltford Community Association News Issue No 150 February / March 2020

Saltford Community Association News Issue No 150 February / March 2020 SCA and Keynsham & District Lions invite you to a Saltford Hall Saturday 7 March 2020 Starting at 7.30pm prompt with teams of up to 6 Tickets £8 per head to include beef or vegetarian curry and rice Available at Saltford Hall Booking Office 01225 874081 (am only), Saltford Community PO/Library or you can buy tickets online via www.buytickets.at/SCAEvents SALTFORD COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION presents Featuring the ‘ABBEY ROADIES’ SATURDAY 15 FEBRUARY 2020 SALTFORD HALL Suitable for ALL ages, singing along, dancing etc. Tickets £15 each including main and dessert From Saltford Community PO/Library, Saltford Hall (weekday mornings) or via www.buytickets.at/SCAEvents COPY DEADLINE FOR APRIL/MAY ISSUE OF SCAN: 10th March 2020 Copy sent by email to [email protected] will be very welcome. www.saltfordhall.co.uk 1 2 Saltford Community Association - Contacts SCA is a Registered Charity—Number 1162948 Hon Chair SCA John Davies 01225 344976 Hon Vice Chair SCA Peter Dando 01225 873917 Hon Treasurer SCA Chris Essex 01225 873878 Hon Secretary SCA Lis Evans 01225 873296 SCAN Distribution Jenny Herring 01225 874631 SCAN Editor e-mail: [email protected] 07770 750327 Hall Manager Christopher Pope 01225 874081 e-mail: [email protected] List of Sectional Organisation Contacts Saltford Drama Club Martin Coles 01179 831288 Saltford Short Mat Bowls Joan Hamblin 01225 872389 Saltford Village Choir Julie Latham 01225 872336 Saltford Panto Club [email protected] SCA Musical Productions [SCAMP] Corrine-Anne Richards 0117 986 0930 The opinions, advice, products and services offered herein are the sole responsibility of the contributors. -

The Survey of Bath and District

The Survey of Bath and District The Magazine of the Survey of Old Bath and Its Associates No.9, June 1998 Editors: Mike Chapman Elizabeth Holland The Rebecca Fountain, taken 1997 by local artist and photographer Edy Scott. The Temperance movement gained momentum from the increased availability of clean drinking water. Previously even children were given wine and ale to drink. The allusion to Rebecca is taken from Genesis 24:15. Included in this issue; An historical review of the Hetling Pump Room and Hetling House by Elizabeth Holland. Extracts from the memoirs of John James Chapman in the early 19th century, concerning his schooldays in Bath and the religious issues of the day. Further research on the historical development of the Ambury by John Macdonald. 1 NEWS FROM THE SURVEY Our article on “Stothert’s Foundry, Southgate Street, Bath” has been published in BIAS Journal 30. This issue of the journal is discussed in “Publications”. We have also contributed a section on the Southgate area to the exhibition at Bath Industrial Heritage Centre, open from June to October. Friends are invited to the opening on Saturday 13 June, at 6.30 p.m. Our special subjects for this display are Stothert and Pitt’s, and Transport. By following up various leads, we have decided on an exact site for the Horse Bath in the Southgate Street area. If commissioned, we shall be glad to write a report on this, but otherwise it is not part of our immediate programme. The same applies to Opie Smith’s brewery, on which a study could be made as has been done with Stothert’s foundry. -

The Survey of Bath and District

The Survey of Bath and District The Magazine of the Survey of Old Bath and Its Associates No.13, June 2000 Editors: Mike Chapman Elizabeth Holland The Walcot and St.Michael’s parish boundary marks on the wall of Ladymead House, taken from the site of the Cornwell spring. _____________ Included in this issue; • Did Hogarth Paint Susanna Chapman? Susan Sloman • The Ken Biggs Architectural Archive Jacky Wibberley • Cornwell, Walcot Street Allan Keevil NEWS FROM THE SURVEY The proposed pictorial booklet on the Guildhall has been deferred to a future date. We are now publishing our study of the Guildhall; unlike our other booklets it centres on the history of the building rather than a whole area. We have received a grant for a further publication, for which we are grateful. It was intended to be used for the Sawclose area, but as that will appear in Bath History later this year, it is now planned to use it for a report on the springs and watercourses of Bath. Our study of the Bimbery area has been completed. Mike spoke on ‘Great Houses of Bimbery’ at the lunchtime lecture last November, and a walk is planned for later on. We are working towards bringing out a Bimbery booklet later this year. This will include two new maps, one an annotation of Palmer’s development map of c.1804-1805, and the other a map created by the Survey of the area c.1770. Our contribution to the exhibition on Walcot Street at the Museum of Bath at Work is now in place and we hope Friends will visit it. -

Compton Dando

COMPTON DANDO FIVE VILLAGES PARISH PLAN Queen Charlton Chewton Keynsham Burnett Woollard Compton Dando September 2010 1 Acknowledgements Sincere thanks to all the volunteers from each of the five villages who have made this plan possible. The steering committee particularly wish to recognise the contribution made by Charles Fallon, the first Chairman of the group, for his drive in setting the ball rolling. Thanks also go to those organisations whose help has been invaluable in this process, in particular Bath & North East Somerset Council, Community Action and other Parish Plan groups. Funding for the process was made available by Quartet Community Foundation. Additional funding was provided by Compton Dando Parish Council. Neither of these organisations has had any editorial impact on the content of this report. Contents Report summary 3 The Parish 4 A Village View 5 The process 10 Results 11 What happens next? 20 Useful information and contacts 20 Parish Map 21 The Action Plan Appendix I Summary of Questionnaire results Appendix II Young People’s Questionnaire results Appendix III Census information 2001 Appendix IV 2 Report summary This parish plan sets out the views of the residents of the five villages within Compton Dando Parish about how they would like their local area to develop in the future. It has been put together by local volunteers, and follows more than a year of information gathering, analysis, discussions and meetings – many held in public – with parishioners in all five of the villages. As a result of this parish plan, it is hoped that future changes planned in the villages and surrounding environment will be informed and shaped by the people who live here.