Keynsham Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curo Housing Estate a Scene of “Deprivation” Keynsham Town Councillor Dave Biddleston Says Pre-War Poverty”

THE WEEK IN East Bristol & North East Somerset FREE Issue 544 26th September 2018 Read by over 40,000 people each week Curo housing estate a scene of “deprivation” Keynsham town councillor Dave Biddleston says pre-war poverty”. vandalism and ant-social behaviour. residents are living in “deprivation” at Curo homes in Last week, a deputation from the 40-plus homes A Facebook page set up by residents shows images of Tintagel Close, claiming “basic sanitary living has been attended the town council meeting to describe some of bare electrical wiring exposed to the elements and other so compromised it's as if Keynsham has moved back to the problems they face as a result of poor maintenance, scenes of neglect. Recently The Week In reported on an arson attack when waste bins were deliberately set alight and although nobody was hurt, considerable damage was caused to neighbouring properties, with the heat even melting drainpipes and guttering. At the time residents reported that the lock on the bin store door had been vandalised and not repaired. Responding to a report by BBC Bristol, Curo claimed that the CCTV system at Tintagel Close had been vandalised beyond repair. This brought an angry reaction from residents who claimed the security cameras have never worked. Continued on page 3 Tintagel Close Concerns at Warmley Funding boost for Problems persist at MP changes position Also in this Community Centre . Keynsham one-way Mangotsfield tip on Brexit week’s issue . page 5 . page 6 . page 12 . page 7 2 The Week in • Wednesday 26th September 2018 Curo housing estate a Public meeting to scene of “deprivation” discuss traffic concerns Continued from page 1 homes at Tintagel Close. -

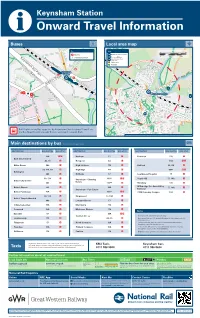

Keynsham Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Keynsham Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Key Key km 0 0.5 A Bus Stop LC Keynsham Leisure Centre 0 Miles 0.25 Station Entrance/Exit M Portavon Marinas Avon Valley Adventure & WP Wildlife Park istance alking d Cycle routes tes w inu 0 m Footpaths 1 B Keynsham C Station A A bb ey Pa r k M D Keynsham Station E WP LC 1 1 0 0 m m i i n n u u t t e e s s w w a a l l k k i i n n g g d d i i e e s s t t c c a a n n Rail Replacement Bus stops are by Keynsham Church (stops D and E on the Bus Map) Stop D towards Bristol, and stop E towards Bath. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at October 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP 19A A E Hanham 17 C Radstock 178 E Bath City Centre ^ A4, 39 E Hengrove A4 D 19A A E Bilbie Green 349 D High Littleton 178 E Saltford 39, A4 E 39, 178, A4 D Highridge A4 D 664* B E Brislington 349 E Hillfields 17 C Southmead Hospital 17 C 39, 178 D 663* B E Staple Hill 17, 19A C Keynsham - Chandag Bristol City Centre Estate 349 E 178** E Timsbury 178 E Willsbridge (for Avon Valley Bristol Airport A4 D 349 E 17, 19A C Keynsham - Park Estate Railway) Bristol Parkway ^ 19A C 665* B E UWE Frenchay Campus 19A C 39, 178 D Kingswood 17, 19A C Bristol Temple Meads ^ 349 E Longwell Green 17 C Cribbs Causeway 19A C Marksbury 178 E Downend 19A C Midsomer Norton 178 E Notes Eastville 17 C 19A A E Newton St Loe Bus routes 17, 39 and A4 operate daily. -

Long, W, Dedications of the Somersetshire Churches, Vol 17

116 TWENTY-THIKD ANNUAL MEETING. (l[ki[rk^. BY W, LONG, ESQ. ELIEVING that a Classified List of the Dedications jl:> of the Somersetshire Churches would be interesting and useful to the members of the Society, I have arranged them under the names of the several Patron Saints as given by Ecton in his “ Thesaurus Kerum Ecclesiasticarum,^^ 1742 Aldhelm, St. Broadway, Douiting. All Saints Alford, Ashcot, Asholt, Ashton Long, Camel West, Castle Cary, Chipstaple, Closworth, Corston, Curry Mallet, Downhead, Dulverton, Dun- kerton, Farmborough, Hinton Blewitt, Huntspill, He Brewers, Kingsdon, King Weston, Kingston Pitney in Yeovil, Kingston] Seymour, Langport, Martock, Merriot, Monksilver, Nine- head Flory, Norton Fitzwarren, Nunney, Pennard East, PoLntington, Selworthy, Telsford, Weston near Bath, Wolley, Wotton Courtney, Wraxhall, Wrington. DEDICATION OF THE SOMERSET CHURCHES. 117 Andrew, St. Aller, Almsford, Backwell, Banwell, Blagdon, Brimpton, Burnham, Ched- dar, Chewstoke, Cleeve Old, Cleve- don, Compton Dundon, Congresbury, Corton Dinham, Curry Rivel, Dowlish Wake, High Ham, Holcombe, Loxton, Mells, Northover, Stoke Courcy, Stoke under Hambdon, Thorn Coffin, Trent, Wells Cathedral, White Staunton, Withypool, Wiveliscombe. Andrew, St. and St. Mary Pitminster. Augustine, St. Clutton, Locking, Monkton West. Barnabas, St. Queen’s Camel. Bartholomew, St. Cranmore West, Ling, Ubley, Yeovilton. Bridget, St. Brean, Chelvy. Catherine, St. Drayton, Montacute, Swell. Christopher, St. Lympsham. CONGAR, St. Badgworth. Culborne, St. Culbone. David, St. Barton St. David. Dennis, St. Stock Dennis. Dubritius, St. Porlock. Dun STAN, St. Baltonsbury. Edward, St. Goathurst. Etheldred, St. Quantoxhead West. George, St. Beckington, Dunster, Easton in Gordano, Hinton St. George, Sand- ford Bret, Wembdon, Whatley. Giles, St. Bradford, Cleeve Old Chapel, Knowle St. Giles, Thurloxton. -

Items from the Public – Statements and Questions

Public Document Pack Joint meeting – West of England Combined Authority Committee and West of England Joint Committee 19 June 2020 Items from the public – statements and questions Agenda Item 6 JOINT MEETING - WEST OF ENGLAND COMBINED AUTHORITY COMMITTEE & WEST OF ENGLAND JOINT COMMITTTEE - 19 JUNE 2020 Agenda item 6 – Items from the public Statements and petitions received (full details set out in following pages): 1. David Redgewell – Transport issues 2. Alison Allan – Climate Emergency Action Plan 3. Gordon Richardson – Protecting disabled passengers - social distancing on buses and trains 4. Cllr Geoff Gollop – Agenda item 19 – Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan specifically. Other items generally on WECA committee agendas 5. Dave Andrews – Trams 6. Gavin Smith – West of England bus strategy / rapid transit 7. Dick Daniel – Sustainable transport improvements 8. Cllr Brenda Massey – Agenda item 19 – Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plan 9. Sue Turner – Prioritising the recovery of the Voluntary Organisations and Social Enterprises sector in the West of England. 10. Tony Jones – Climate emergency planning 11. Faye Dicker – JLTP4 - new road proposed to be built from the A4 to the A37 and onto Whitchurch Lane 12. Kim Hicks – JLTP4 – consultation / engagement 13. Julie Boston – bus travel for young people 14. Sam Morris – WECA’s climate emergency report and infrastructure plans 15. Susan Carter – Joint Green Infrastructure Strategy 16. Cllr Martin Fodor – Climate Emergency Action Plan 17. Cllr Clive Stevens – Strategic -

River Avon, Road & Rail Walk

F e r r y Riverside Heritage Walks R o 8 a d River Avon, Road 1 Old Lock & Weir / The Chequers & Rail Walk Londonderry 7 Wharf Riverside walk rich in historic and wildlife interest. Optional extension loop A4 exploring hidden woodlands and geology A 41 Somerdale 75 6 Route Description: Hanham pubs to Keynsham Lock or complete loop 2 1 Head east along the 60 mins 5 River Avon Trail. Loop: 100 mins Key 3 Route 4 See traces of the old 2 m / 3.25 km Route guide Londonderry Wharf Loop: 4.5 / 7.25 km 1 The Lock Keeper River Avon Trail and The Dramway Level, grassy Short cut that once carried paths coal from Kingswood Loop: Some steep Refreshments Keynsham to the river. Look out steps, rough ground Shop for cormorants. and high stiles Pub You will see the development at former Cadbury’s Somerdale factory Arrive at Keynsham Lock on the – the site of a Roman town. Kennet & Avon Canal. Continue 2 beneath the old bridge beside The Lock Keeper pub, and up onto the bridge. You can now retrace your steps to the start or continue on loop walk. Drop down along the path over When you have crossed both the rail Route extension the wild grassland, keeping the 5 and river bridge, turn right and zig- Turn left and left again to road close by on your right. zag uphill to find a wooden stile. arrive on the main road The grassy path is bordered by Cross here and drop down sharply (A4175). -

Modernising the Street Lighting Network Where You Live

Where we will be working Modernising the street lighting and when SSE Enterprise are our delivery partners for this work. They will be carrying out the network where you live replacements on a street-by-street basis in the towns and Parishes shown below. Replacing the lantern usually takes around 30 minutes per column and is carried out from a mobile working platform, minimising any disruption for people living nearby. Working in partnership with Bath & North East Somerset Council Installation of the LED lights starts December 2016 and continues on a rolling programme for 6 months. The list below shows the towns and villages in which we will be working. We expect the work to take place in your street around 2 to 4 weeks after you receive this leaflet. Bathampton Clutton Batheaston & Shockerwick Temple Cloud & Camley Bathford Camerton Charlcombe & Lansdown Timsbury Southstoke, C. Down, L. Stoke, Midford Peasedown St John & Carlingcot Midsomer Norton & Radstock Paulton Keynsham Farrington Gurney Saltford High Littleton & Hallatrow Whitchurch Marksbury & Stanton Prior Installing LED lighting to create a welcoming Farmborough Bishop Sutton, Stowey Sutton environment and deliver significant energy and cost savings in Bath & North East Somerset Ref: LED/PH2 For more information, visit our web site at: www.bathnes.gov.uk./LED or email us at: [email protected] Council Connect 01225 39 40 41 Up to 11% of Bath & North East Somerset’s carbon FrequentlyFrequently AskedAsked QuestionsQuestions emissions are generated by its street lights. n Do LEDs have any health risks? n Will it shine in my window? The existing street lights across the region are also in a variable condition, Public Health England has carried out The light from an LED lamp is far more with a large number of aging lights requiring replacement. -

Avon Archaeology

1 l ~~iro~ AVON ARCHAEOLOGY \ '' ~\(i;--.. j I \ -:_1 c~ r" ,-.-..ii. '\~-- ~ ' Volume 6 BRISTOLAND AVONARCHAEOLOGY 6 1987 CONTENTS Address by L.V. Grinsell on the occasion of the 25th Anniversa!Y of B(A)ARG 2 L.V. Grinsell Bibliography 1972-1988 3 compiled by N. Thomas Domesday Keynsham - a retrospective examination of an old English Royal Estate 5 M. Whittock Excavations in Bristol in 1985-86 11 R. Burchill, M. Coxah, A. Nicholson & M. W. Ponsford The Lesser Cloister and a medieval drain at St. Augustine's Abbey, Bristol 31 E.J. Boore Common types of earthenware found in the Bristol area 35 G.L. Good & V.E.J. Russett Avon Archaeology 1986 and 1987 44 R. Iles & A. Kidd A Bi-facial polished-edge flint knife from Compton Dando 57 Alan Saville Excavations at Burwalls House, Bristol, 1980 58 N.M. Watson Cromhall Romano-British villa 60 Peter Ellis An Anglo-Saxon strap-end from Winterbourne, Bristol 62 J. Stewart Eden rediscovered at Twerton, Bath 63 Mike Chapman St. John's Keynsham - results of excavation, 1979 64 Peter Ellis An 18th-19th century Limekiln at Water Lane, Temple, Bristol 66 G.L. Good Medieval floor tiles from Winterbrmrne 70 J.M. Hunt & J.R. Russell Book reviews 72 (c) Authors and Bristol & Avon Archaeological Research Group COMMITTEE 1987-88 Chairman N. Thomas Vice-Chairman A.J. Parker Secretary J. Bryant Treasurer J. Russell Membership Secretary A. Buchan Associates Secretary G. Dawson Fieldwork Advisor M. Ponsford Editor, Special Publications R. Williams Publicity Officer F. Moor Editor, BAA R. -

Tickets Are Accepted but Not Sold on This Service

May 2015 Guide to Bus Route Frequencies Route Frequency (minutes/journeys) Route Frequency (minutes/journeys) No. Route Description / Days of Operation Operator Mon-Sat (day) Eves Suns No. Route Description / Days of Operation Operator Mon-Sat (day) Eves Suns 21 Musgrove Park Hospital , Taunton (Bus Station), Monkton Heathfield, North Petherton, Bridgwater, Dunball, Huntspill, BS 30 1-2 jnys 60 626 Wotton-under-Edge, Kingswood, Charfield, Leyhill, Cromhall, Rangeworthy, Frampton Cotterell, Winterbourne, Frenchay, SS 1 return jny Highbridge, Burnham-on-Sea, Brean, Lympsham, Uphill, Weston-super-Mare Daily Early morning/early evening journeys (early evening) Broadmead, Bristol Monday to Friday (Mon-Fri) start from/terminate at Bridgwater. Avonrider and WestonRider tickets are accepted but not sold on this service. 634 Tormarton, Hinton, Dyrham, Doyton, Wick, Bridgeyate, Kingswood Infrequent WS 2 jnys (M, W, F) – – One Ticket... 21 Lulsgate Bottom, Felton, Winford, Bedminster, Bristol Temple Meads, Bristol City Centre Monday to Friday FW 2 jnys –– 1 jny (Tu, Th) (Mon-Fri) 635 Marshfield, Colerne, Ford, Biddestone, Chippenham Monday to Friday FS 2-3 jnys –– Any Bus*... 26 Weston-super-Mare , Locking, Banwell, Sandford, Winscombe, Axbridge, Cheddar, Draycott, Haybridge, WB 60 –– (Mon-Fri) Wells (Bus Station) Monday to Saturday 640 Bishop Sutton, Chew Stoke, Chew Magna, Stanton Drew, Stanton Wick, Pensford, Publow, Woollard, Compton Dando, SB 1 jny (Fri) –– All Day! 35 Bristol Broad Quay, Redfield, Kingswood, Wick, Marshfield Monday to Saturday -

West of England Joint Spatial Plan Publication Document November 2017

West of England Joint Spatial Plan Publication Document November 2017 Contents Foreword 5 Chapter 1: Introduction 6 Chapter 2: Vision, Critical Issues and Strategic Priorites 8 Chapter 3: Formulating the Spatial Strategy 14 Chapter 4: Policy Framework 18 Chapter 5: Delivery and Implementation 47 www.jointplanningwofe.org.uk 3 MANCHESTER BIRMINGHAM CARDIFF WEST OF ENGLAND LONDON SOUTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE BRISTOL NORTH SOMERSET BATH & NORTH EAST SOMERSET 4 We have to address key economic and social Foreword imbalances within our city region and support The West of England (WoE) currently faces a key inclusive growth. In the WoE, we need to take steps challenge; how to accommodate and deliver to ensure more homes are built of the right type and much needed new homes, jobs and infrastructure mix, and in locations that people and businesses alongside protecting and enhancing our unique need. Businesses should be able to locate where and high quality built and natural environment. It is they can be most efficient and create jobs, enabling this combination that will create viable, healthy and people to live, rent and own homes in places which attractive places. This is key to the ongoing success are accessible to where they work. Transport and of the West of England which contributes to its infrastructure provision needs to be in place up appeal and its high quality of life. front or to keep pace with development to support sustainable growth. Many people feel passionately about where they live and the impact new growth might have on their local The challenges involved and the scale of the issues communities. -

Issue-371.Pdf

The Week in East Bristol & North East Somerset FREE Issue no 371 14th May 2015 Read by over 30,000 people every week In this week’s issue ...... pages 6 & 19 Election shocks across the region . Parliamentary and local government results page 5 Final journey for railway enthusiast . Tribute to Bob Hutchings MBE page 22 Temporary home for Lyde Green Primary . New school will spend first year at Downend in 2 The Week • Thursday 14th May 2015 Well, a week ago we wrote that nobody seemed to have any Electionreal idea of how the General Election would turn out,shockwave and in the end, neither winners, losers nor commentators came anywhere close to predicting the result. In the Parliamentary constituencies we cover, we have seen marginal seats become safe Conservative seats and a Liberal Democrat minister lose his job. UKIP and the Green Party went from 'wasted votes' to significant minority parties. Locally, two councils which have had no overall control for the last eight years are now firmly in the hands of Conservative councillors while Bristol, which elects a third of its council on an annual The count at Bath University basis, remains a hung administration. The vote for its elected mayor takes place next year. You can read all about the constituency and local government Dawn was breaking over Bath and Warmley where The Week elections last week on pages 6 & 19. In was present at the counts for the North East Somerset and Our cover picture shows Clemmie, daughter of Kingswood MP Kingswood constituencies, before we knew that both sitting Chris Skidmore at last week's vote. -

7:52 PM 25/01/2019 Page 1 Somerset ASA County Championships 2019 - 26/01/2019 to 10/02/2019 Meet Program - Sunday 27Th January 2019

Somerset ASA Championship Meet HY-TEK's MEET MANAGER 7.0 - 7:52 PM 25/01/2019 Page 1 Somerset ASA County Championships 2019 - 26/01/2019 to 10/02/2019 Meet Program - Sunday 27th January 2019 Heat 7 of 14 Prelims Starts at 09:59 AM Event 13 Girls 10 & Over 200 LC Meter Backstroke 1 Isla Bennie 14 Bridgwater 2:42.10 Lane Name Age Team Seed Time 2 Bluebell Clayton 16 Millfield 2:41.27 Heat 1 of 14 Prelims Starts at 09:30 AM 3 Imogen Bamber 13 CLEW-SW 2:41.00 CLEW-SW 3:27.20 1 Amelia Vincent 10 4 Isabel Blackhurst 12 Weston S M 2:39.97 CLEW-SW 3:20.20 2 Amelie Dorrington 11 5 Eva Farmery 16 CLEW-SW 2:40.84 Keynsham-SW 3:15.90 3 Aneliese Hunt 11 6 Natasha Edmondston-Low 17 Weston S M 2:41.03 TauntonDeane 3:13.40 4 Francesca Hanson 11 7 Grace Olding 14 Millfield 2:42.00 Street 3:15.86 5 Alesha Nisbet 10 8 Chloe Soverall 14 Weston S M 2:42.34 Millfield 3:16.80 6 Gabriella Relton 11 Heat 8 of 14 Prelims Starts at 10:04 AM Weston S M 3:24.80 7 Sunnie Rose Harling 11 1 Kayla Pike 15 Street 2:39.24 Keynsham-SW 3:27.80 8 Daisy Oliver 11 2 Laura-Ann Marshman 13 Weston S M 2:38.95 Heat 2 of 14 Prelims Starts at 09:36 AM 3 Shannon Hooper 17 Ast Burnham 2:38.05 TauntonDeane 3:12.80 1 Olivia Barlow 11 4 Kyna Galvin 15 Millfield 2:38.00 Yeovil 3:08.10 2 Kathleen Hague 11 5 Rebecca Hollier 14 Backwell 2:38.02 Street 3:06.24 3 Lucy Williams 12 6 Lily Hastings-McMahon 14 Frome 2:38.80 Millfield 3:00.90 4 Bianca Gomez-Velasco 12 7 Alice Harvey 14 Keynsham-SW 2:39.00 Millfield 3:02.70 5 Annabelle Suffield 11 8 Katie Sherlock 13 Millfield 2:39.50 Chard 3:07.00 -

Area 1: Thrubwell Farm Plateau

Area 1: Thrubwell Farm Plateau Summary of Landscape Character • Clipped hedges which are often ‘gappy’ and supplemented by sheep netting • Late 18th and early 19th century rectilinear field layout at north of area • Occasional groups of trees • Geologically complex • Well drained soils • Flat or very gently undulating plateau • A disused quarry • Parkland at Butcombe Court straddling the western boundary • Minor roads set out on a grid pattern • Settlement within the area consists of isolated farms and houses For detailed Character Area map see Appendix 3 23 Context Bristol airport on the plateau outside the area to the west. Introduction Land-uses 7.1.1 The character area consists of a little over 1sq 7.1.6 The land is mainly under pasture and is also km of high plateau to the far west of the area. The plateau used for silage making. There is some arable land towards extends beyond the Bath and North East Somerset boundary the north of the area. Part of Butcombe Court parkland into North Somerset and includes Felton Hill to the north falls within the area to the west of Thrubwell Lane. and Bristol airport to the west. The southern boundary is marked by the top of the scarp adjoining the undulating Fields, Boundaries and Trees and generally lower lying Chew Valley to the south. 7.1.7 Fields are enclosed by hedges that are generally Geology, Soils and Drainage trimmed and often contain few trees. Tall untrimmed hedges are less common. Hedges are typically ‘gappy’ and of low 7.1.2 Geologically the area is complex though on the species diversity and are often supplemented with sheep- ground this is not immediately apparent.