Bird Damage in Tree Fruits Are Higher in Low-Fruit- Abundance Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Apple Clones in the United States

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. 5 ARS 34-37-1 May 1963 A Survey of Apple Clones in the United States u. S. DFPT. OF AGRffini r U>2 4 L964 Agricultural Research Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PREFACE This publication reports on surveys of the deciduous fruit and nut clones being maintained at the Federal and State experiment stations in the United States. It will b- published in three c parts: I. Apples, II. Stone Fruit. , UI, Pears, Nuts, and Other Fruits. This survey was conducted at the request of the National Coor- dinating Committee on New Crops. Its purpose is to obtain an indication of the volume of material that would be involved in establishing clonal germ plasm repositories for the use of fruit breeders throughout the country. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Gratitude is expressed for the assistance of H. F. Winters of the New Crops Research Branch, Crops Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, under whose direction the questionnaire was designed and initial distribution made. The author also acknowledges the work of D. D. Dolan, W. R. Langford, W. H. Skrdla, and L. A. Mullen, coordinators of the New Crops Regional Cooperative Program, through whom the data used in this survey were obtained from the State experiment stations. Finally, it is recognized that much extracurricular work was expended by the various experiment stations in completing the questionnaires. : CONTENTS Introduction 1 Germany 298 Key to reporting stations. „ . 4 Soviet Union . 302 Abbreviations used in descriptions .... 6 Sweden . 303 Sports United States selections 304 Baldwin. -

Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota (H1558)

H1558 (Revised June 2019) Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota TH DAK R OT O A N Dear Friends, We are excited to bring you this publication. Its aim is to help you establish a fruit orchard in your community. Such a project combines horticulture, nutrition, community vitality, maybe even youth. All of these are areas in which NDSU Extension has educational focuses. Local community orchard projects can improve the health of those who enjoy its bounty. This Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota publication also is online at www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/lawns-gardens-trees/starting-a-community- orchard-in-north-dakota so you can have it in a printable PDF or mobile-friendly version if you don’t have the book on hand. True to our mission, NDSU Extension is proud to empower North Dakotans to improve their lives and communities through science-based education by providing this publication. We also offer many other educational resources focused on other horticultural topics such as gardening, lawns and trees. If you’re especially passionate about horticulture and sharing your knowledge, consider becoming an NDSU Extension Master Gardener. After training, as a Master Gardener volunteer, you will have the opportunity to get involved in a wide variety of educational programs related to horticulture and gardening in your local community by sharing your knowledge and passion for horticulture! Learn about NDSU Extension horticulture topics, programs, publications and more at www.ag.ndsu.edu/extension/lawns_gardens_trees. We hope this publication is a valuable educational resource as you work with community orchards in North Dakota. -

Using Whole-Genome SNP Data to Reconstruct a Large Multi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna Muranty et al. BMC Plant Biology (2020) 20:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2171-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Using whole-genome SNP data to reconstruct a large multi-generation pedigree in apple germplasm Hélène Muranty1*† , Caroline Denancé1†, Laurence Feugey1, Jean-Luc Crépin2, Yves Barbier2, Stefano Tartarini3, Matthew Ordidge4, Michela Troggio5, Marc Lateur6, Hilde Nybom7, Frantisek Paprstein8, François Laurens1 and Charles-Eric Durel1 Abstract Background: Apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.) is one of the most important fruit tree crops of temperate areas, with great economic and cultural value. Apple cultivars can be maintained for centuries in plant collections through grafting, and some are thought to date as far back as Roman times. Molecular markers provide a means to reconstruct pedigrees and thus shed light on the recent history of migration and trade of biological materials. The objective of the present study was to identify relationships within a set of over 1400 mostly old apple cultivars using whole-genome SNP data (~ 253 K SNPs) in order to reconstruct pedigrees. Results: Using simple exclusion tests, based on counting the number of Mendelian errors, more than one thousand parent-offspring relations and 295 complete parent-offspring families were identified. Additionally, a grandparent couple was identified for the missing parental side of 26 parent-offspring pairings. Among the 407 parent-offspring relations without a second identified parent, 327 could be oriented because one of the individuals was an offspring in a complete family or by using historical data on parentage or date of recording. -

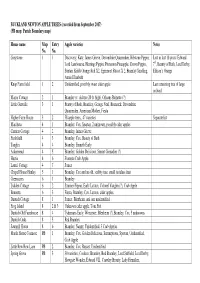

BUCKLAND NEWTON APPLE TREES (Recorded from September 2017) (PB Map: Parish Boundary Map)

BUCKLAND NEWTON APPLE TREES (recorded from September 2017) (PB map: Parish Boundary map) House name Map Entry Apple varieties Notes No. No. Greystone 1 1 Discovery, Katy, James Grieve, Devonshire Quarrenden, Ribstone Pippin, Lost in last 10 years: Edward Lord Lambourne, Herrings Pippin, Pitmaston Pineapple, Crown Pippin, 7th , Beauty of Bath, Lord Derby, Suntan, Kidds Orange Red X2, Egremont Russet X 2, Bramley Seedling, Ellison’s Orange Annie Elizabeth Knap Farm field 1 2 Unidentified, possibly sweet cider apple Last remaining tree of large orchard Manor Cottage 2 1 Bramley (v. old tree 20 ft. high), Orleans Reinette (?) Little Gunville 3 1 Beauty of Bath, Bramley, George Neal, Bismarck, Devonshire Quarrenden, American Mother, Fiesta Higher Farm House 3 2 58 apple trees,, 47 varieties Separate list Marcheta 4 1 Bramley, Cox, Spartan, 2 unknown, possibly cider apples Carriers Cottage 4 2 Bramley, James Grieve Freshfield 4 3 Bramley, Cox, Beauty of Bath Tanglin 4 4 Bramley, Emneth Early Askermead 4 5 Bramley, Golden Delicious, Sunset Grenadier (?) Hestia 4 6 Evereste Crab Apple Laurel Cottage 4 7 Sunset Chapel House Henley 5 1 Bramley, Cox and an old, scabby tree, small tasteless fruit Greenacres 6 1 Bramley Lydden Cottage 6 2 Sturmer Pippin, Early Laxton, Colonel Vaughn (?), Crab Apple Bennetts 6 3 Fiesta, Bramley, Cox, Laxton, cider apples Duntish Cottage 8 1 Sunset, Blenheim, and one unidentified Frog Island 8 2 & 3 Unknown cider apple, Tom Putt Duntish Old Farmhouse 8 4 Tydemans Early, Worcester, Blenheim (?),Bramley, Cos, 5 unknowns -

2017 Annual Report Bismarck Parks and Recreation District Operations

2017 Annual Report Bismarck Parks and Recreation District Operations Division 1 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Role of the Operations Division ......................................................................................................................... 3 Human Resources ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Full-Time Staff ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Seasonal Staff ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Labor Breakdown General Maintenance .................................................................................................... 8 Total Hours per Location ........................................................................................................................... 8 Total Hours per Task ................................................................................................................................ 10 Labor Breakdown Park Planner ................................................................................................................. 11 Training.......................................................................................................................................................... -

Apple Pollination Groups

Flowering times of apples RHS Pollination Groups To ensure good pollination and therefore a good crop, it is essential to grow two or more different cultivars from the same Flowering Group or adjacent Flowering Groups. Some cultivars are triploid – they have sterile pollen and need two other cultivars for good pollination; therefore, always grow at least two other non- triploid cultivars with each one. Key AGM = RHS Award of Garden Merit * Incompatible with each other ** Incompatible with each other *** ‘Golden Delicious’ may be ineffective on ‘Crispin’ (syn. ‘Mutsu’) Flowering Group 1 Very early; pollinated by groups 1 & 2 ‘Gravenstein’ (triploid) ‘Lord Suffield’ ‘Manks Codlin’ ‘Red Astrachan’ ‘Stark Earliest’ (syn. ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’) ‘Vista Bella’ Flowering Group 2 Pollinated by groups 1,2 & 3 ‘Adams's Pearmain’ ‘Alkmene’ AGM (syn. ‘Early Windsor’) ‘Baker's Delicious’ ‘Beauty of Bath’ (partial tip bearer) ‘Beauty of Blackmoor’ ‘Ben's Red’ ‘Bismarck’ ‘Bolero’ (syn. ‘Tuscan’) ‘Cheddar Cross’ ‘Christmas Pearmain’ ‘Devonshire Quarrenden’ ‘Egremont Russet’ AGM ‘George Cave’ (tip bearer) ‘George Neal’ AGM ‘Golden Spire’ ‘Idared’ AGM ‘Irish Peach’ (tip bearer) ‘Kerry Pippin’ ‘Keswick Codling’ ‘Laxton's Early Crimson’ ‘Lord Lambourne’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Maidstone Favourite’ ‘Margil’ ‘Mclntosh’ ‘Red Melba’ ‘Merton Charm’ ‘Michaelmas Red’ ‘Norfolk Beauty’ ‘Owen Thomas’ ‘Reverend W. Wilks’ ‘Ribston Pippin’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Ross Nonpareil’ ‘Saint Edmund's Pippin’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Striped Beefing’ ‘Warner's King’ AGM (triploid) ‘Washington’ (triploid) ‘White Transparent’ Flowering Group 3 Pollinated by groups 2, 3 & 4 ‘Acme’ ‘Alexander’ (syn. ‘Emperor Alexander’) ‘Allington Pippin’ ‘Arthur Turner’ AGM ‘Barnack Orange’ ‘Baumann's Reinette’ ‘Belle de Boskoop’ AGM (triploid) ‘Belle de Pontoise’ ‘Blenheim Orange’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Bountiful’ ‘Bowden's Seedling’ ‘Bramley's Seedling’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Brownlees Russett’ ‘Charles Ross’ AGM ‘Cox's Orange Pippin’ */** ‘Crispin’ (syn. -

June-12-2020-CB-Digi

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 63, No. 11 Friday, June 12, 2020 $4.00 50 Amazing ’Series Memories Drama, wild moments highlight the history of the College World Series for the past 73 years. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball MAHA, Neb. — Since there is no College World Series this Oyear because of the coronavirus pandemic, Collegiate Baseball thought it would be a good idea to remind people what a remarkable event this tournament is. So we present the 50 greatest memories He had not hit a home run all season in CWS history. long. 1. Most Dramatic Moment To End With one runner on, he hit the only Game: With two outs in the bottom of the walk-off homer to win a College World ninth in the 1996 College World Series Series in history as it barely cleared the championship game, Miami (Fla.) was on right field wall as LSU pulled off a 9-8 the cusp of winning the national title over win in the national title game. Louisiana St. with 1-run lead. 2. Greatest Championship Game: With one runner on, LSU’s Warren Southern California and Florida State Morris stepped to the plate. played the greatest College World Series He did not play for 39 games due to a championship game in history. WILD CELEBRATIONS — The College World Series in Omaha has featured fractured hamate bone in his right wrist The Trojans beat the Seminoles, 2-1 remarkable moments over the past 73 years, including plenty of dog piles to and only came back to the starting lineup celebrate national championships. -

Applied to the Buying-In Prices for Fruit and Vegetables 1 . in Annex VIII, The

24 . 6 . 89 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 177/37 COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 1822/89 of 23 June 1989 amending Regulation ( EEC) No 3587/86 fixing the conversion factors to be applied to the buying-in prices for fruit and vegetables THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES , grapes produced with a view to the obligatory distillation of wine made from table grapes ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the Management Committee for Fruit and Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 1035/72 Vegetables has not delivered an opinion within the time of 18 May 1972 on the common organization of the limit set by its chairman, market in fruit and vegetables ('), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 1 1 19/89 (2), and in particular Article HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION : 16 (4) thereof, Whereas Commission Regulation (EEC) No 3587/86 (J), Article 1 as last amended by Regulation (EEC) No 2040/88 (4), fixes the conversion factors permitting the calculation of the Regulation (EEC) No 3587/86 is hereby amended as prices at which products with characteristics different follows : from those of products used for the fixing of the basic 1 . In Annex VIII, the list of varieties of large pears is and buying-in prices are bought in ; replaced by the list set out in Annex I hereto . Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 920/89 (5) lays down quality standards for citrus fruit, apples and 2. The first indent of point (b) in Annexe IX is replaced pears ; whereas the provisions of Regulation (EEC) No by the following : 3587/86 should accordingly by adapted to those II . -

Street Tree Guide

Oak, Hybrid Quercus species Hackberry, Common Celtis occidentalis Maple, Silver Acer saccharinum NATIVE SPECIES - Tolerates harsh urban conditions. Deep rooted. Iron Chlorosis can be a major problem when planted in high alkaline soils. Use Crimson Spire Quercus robur x alba ‘Crimschmidt’ Rough, corky bark considered ornamental interest. tree wrap to protect the bark during the winter months. A hybrid of White Oak & English Oak that has a Susceptible to Nipple Gall (aesthetic problem). Height: 50’ fastigate habit. Height: 50’ Spread: 40’ Spread: 45’ Height: 45’ Spread: 15’ Shape: Oval Shape: Round Street Tree Guide Fall Color: Rusty Red Moisture: Dry - Wet Moisture: Dry - Moist Boulevard: Medium Salt Tolerance: Sensitive Salt Tolerance: Fall Color: Yellow Sensitive Boulevard: Extra Large Regal Prince Quercus robur x bicolor ‘Long’ Fall Color: Yellow Forestry Division Recommended: A cross between English Oak & Swamp White Oak. Boulevard: Large Silver Cloud, Silver Queen Recommended: Delta [701] 355-1733 Height: 50’ Spread: 25’ Fall Color: Yellow Boulevard Planting Permit Requests Available Online Boulevard: Medium www.bismarcknd.gov/forestry Tilia Americana Pine, Ponderosa Pinus ponderosa Linden, American Retains needles all year long (conifer). Needles approximately 5 inches in length. NATIVE SPECIES - The pyramidal growth is perfect for areas Partners in Planting (PIP) Boulevard Width where height is needed, but width is limited. Fragrant flowers Produces brown cones. Pine needle scale is a common insect pest. Prairie Stature Quercus x bimundorum ‘Midwest’ Program Categories in spring. American Linden is the largest variety of Linden A hybrid of English Oak & White Oak with a pyramidal form. REIMBURSEMENT RATE Height: 60’ Small = 4’ or larger Proven very cold hardy in NDSU trials. -

R Graphics Output

Aberystwyth University Development of a minimal KASP marker panel for distinguishing genotypes in apple collections Winfield, Mark; Burridge, Amanda; Ordidge, Matthew; Harper, Helen; Wilkinson, Paul; Thorogood, Danny; Copas, Liz; Edwards, Keith; Barker, Gary Published in: PLoS One DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242940 Publication date: 2020 Citation for published version (APA): Winfield, M., Burridge, A., Ordidge, M., Harper, H., Wilkinson, P., Thorogood, D., Copas, L., Edwards, K., & Barker, G. (2020). Development of a minimal KASP marker panel for distinguishing genotypes in apple collections. PLoS One, 15(11), [e0242940]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242940 Document License CC BY General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

A High-Throughput Method for Genotyping S-Rnase Alleles in Apple

Mol Breeding (2016) 36:24 DOI 10.1007/s11032-016-0448-0 A high-throughput method for genotyping S-RNase alleles in apple Bjarne Larsen . Marian Ørgaard . Torben Bo Toldam-Andersen . Carsten Pedersen Received: 15 October 2015 / Accepted: 8 February 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract We present a new efficient screening tool most common among the Danish cultivars followed by for detection of S-alleles in apple. The protocol using S1 and S7 (both 27 %). The alleles S36 and S40 not general and multiplexed primers for PCR reaction and previously reported from M. domestica were found in fragment detection on an automatized capillary DNA 6 and 17 cultivars, respectively. Complete allelic sequencer exposed a higher number of alleles than any composition was found in 91 % of the 369 diploid previous studies. Analysis of alleles is made on basis accessions and in 86 % of the 63 triploids concerned. of three individual fragment sizes making the allele We further identified a relatively high frequency of interpretation highly accurate. The method was S33 and S34, which has not been considered by most employed to genotype 432 Malus accessions and previous studies. The protocol presented here is easy exposed 25 different S-alleles in a selection of Malus to adopt and saves both time and work effort compared domestica cultivars of mainly Danish origin (402 to previous methods. The robustness is illustrated by accessions) as well as a selection of other Malus the great accuracy and a high number of S-alleles species (30 accessions). -

Apple Fruiting

Apple Fruiting ________________________________________________________________________ Spur and Semi-spur Apple Varieties – Over 1000 spur and semi-spur varieties listed. Apple trees that have fruit on spurs or semi-spurs are more dwarfing. They also require special pruning techniques. Tip and Partial-tip Apple Varieties – Over 350 varieties listed. Fruit are borne on the tip of the branches, and are weeping and require little to no pruning. ________________________________________________________________________ Apple Fruiting 1 12/8/06 SPUR-TYPE FRUITING APPLES FOR THE HOME ORCHARD For home orchardists there are several advantages in growing spur–type trees. As the name indicates, the fruit is borne on spurs. Spurs are slow growing leafy shoots and have a mixed terminal bud. A mixed terminal bud will produce shoot and flowers. In apples, spurs develop on two–year old shoots from axillary buds located at the base of each leaf. Axillary buds on a spur can give rise to shoots or new spurs. A branched spur system forms after several years when new spur form on old spurs. Spur–type strains are more dwarfing than the standard stain. When spur and standard strains were compared in Washington rootstock trials, the spurs were 25% smaller than standard stains. Spur–type apples have a growing and fruiting characteristic in which lateral (axillary) buds on two year old wood gives rise to a higher portion of spurs and fewer lateral shoots than occur with standard growth habits. This gives the tree a more open canopy and compact growth habit than standard trees. Research indicates that they have approximately half the canopy volume of standard strains.