Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Apple Clones in the United States

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. 5 ARS 34-37-1 May 1963 A Survey of Apple Clones in the United States u. S. DFPT. OF AGRffini r U>2 4 L964 Agricultural Research Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PREFACE This publication reports on surveys of the deciduous fruit and nut clones being maintained at the Federal and State experiment stations in the United States. It will b- published in three c parts: I. Apples, II. Stone Fruit. , UI, Pears, Nuts, and Other Fruits. This survey was conducted at the request of the National Coor- dinating Committee on New Crops. Its purpose is to obtain an indication of the volume of material that would be involved in establishing clonal germ plasm repositories for the use of fruit breeders throughout the country. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Gratitude is expressed for the assistance of H. F. Winters of the New Crops Research Branch, Crops Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, under whose direction the questionnaire was designed and initial distribution made. The author also acknowledges the work of D. D. Dolan, W. R. Langford, W. H. Skrdla, and L. A. Mullen, coordinators of the New Crops Regional Cooperative Program, through whom the data used in this survey were obtained from the State experiment stations. Finally, it is recognized that much extracurricular work was expended by the various experiment stations in completing the questionnaires. : CONTENTS Introduction 1 Germany 298 Key to reporting stations. „ . 4 Soviet Union . 302 Abbreviations used in descriptions .... 6 Sweden . 303 Sports United States selections 304 Baldwin. -

Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota (H1558)

H1558 (Revised June 2019) Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota TH DAK R OT O A N Dear Friends, We are excited to bring you this publication. Its aim is to help you establish a fruit orchard in your community. Such a project combines horticulture, nutrition, community vitality, maybe even youth. All of these are areas in which NDSU Extension has educational focuses. Local community orchard projects can improve the health of those who enjoy its bounty. This Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota publication also is online at www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/lawns-gardens-trees/starting-a-community- orchard-in-north-dakota so you can have it in a printable PDF or mobile-friendly version if you don’t have the book on hand. True to our mission, NDSU Extension is proud to empower North Dakotans to improve their lives and communities through science-based education by providing this publication. We also offer many other educational resources focused on other horticultural topics such as gardening, lawns and trees. If you’re especially passionate about horticulture and sharing your knowledge, consider becoming an NDSU Extension Master Gardener. After training, as a Master Gardener volunteer, you will have the opportunity to get involved in a wide variety of educational programs related to horticulture and gardening in your local community by sharing your knowledge and passion for horticulture! Learn about NDSU Extension horticulture topics, programs, publications and more at www.ag.ndsu.edu/extension/lawns_gardens_trees. We hope this publication is a valuable educational resource as you work with community orchards in North Dakota. -

Using Whole-Genome SNP Data to Reconstruct a Large Multi

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio istituzionale della ricerca - Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna Muranty et al. BMC Plant Biology (2020) 20:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2171-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Using whole-genome SNP data to reconstruct a large multi-generation pedigree in apple germplasm Hélène Muranty1*† , Caroline Denancé1†, Laurence Feugey1, Jean-Luc Crépin2, Yves Barbier2, Stefano Tartarini3, Matthew Ordidge4, Michela Troggio5, Marc Lateur6, Hilde Nybom7, Frantisek Paprstein8, François Laurens1 and Charles-Eric Durel1 Abstract Background: Apple (Malus x domestica Borkh.) is one of the most important fruit tree crops of temperate areas, with great economic and cultural value. Apple cultivars can be maintained for centuries in plant collections through grafting, and some are thought to date as far back as Roman times. Molecular markers provide a means to reconstruct pedigrees and thus shed light on the recent history of migration and trade of biological materials. The objective of the present study was to identify relationships within a set of over 1400 mostly old apple cultivars using whole-genome SNP data (~ 253 K SNPs) in order to reconstruct pedigrees. Results: Using simple exclusion tests, based on counting the number of Mendelian errors, more than one thousand parent-offspring relations and 295 complete parent-offspring families were identified. Additionally, a grandparent couple was identified for the missing parental side of 26 parent-offspring pairings. Among the 407 parent-offspring relations without a second identified parent, 327 could be oriented because one of the individuals was an offspring in a complete family or by using historical data on parentage or date of recording. -

Bird Damage in Tree Fruits Are Higher in Low-Fruit- Abundance Contexts

Crop Protection 90 (2016) 40e48 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Crop Protection journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Proportions of bird damage in tree fruits are higher in low-fruit- abundance contexts * Catherine A. Lindell a, b, c, , Karen M.M. Steensma d, Paul D. Curtis e, Jason R. Boulanger e, 1, Juliet E. Carroll f, Colleen Burrows g, David P. Lusch h, Nikki L. Rothwell i, Shayna L. Wieferich b, 2, Heidi M. Henrichs e, Deanna K. Leigh j, 3, Rachael A. Eaton a, b, c, George M. Linz k a Department of Integrative Biology, Michigan State University, 288 Farm Ln. Rm. 203, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA b Center for Global Change and Earth Observations, Michigan State University, 1405 S. Harrison Rd., Manly Miles Building, East Lansing, MI 48823, USA c Ecology, Evolutionary Biology, and Behavior, Michigan State University, 103 Giltner Hall, 293 Farm Ln. Rm. 103, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA d Biology Department, Trinity Western University, 7600 Glover Rd, Langley, BC V2Y 1Y1, Canada e Department of Natural Resources, Cornell University, Room 222 Fernow Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA f New York State IPM Program, 630 W. North St, Geneva, NY 14456, USA g Washington State University Whatcom County Extension, 1000 N Forest St, Suite 201, Bellingham, WA 98225, USA h Department of Geography, Environment and Spatial Sciences, Michigan State University, 673 Auditorium Rd. Rm. 212, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA i Northwest Michigan Horticultural Research Station, Michigan State University, 6686 S. Center Hwy, Traverse City, MI 49684, USA j Huxley College of the Environment, Western Washington University, 516 High St., Bellingham, WA 98225, USA k USDA/APHIS Wildlife Services National Wildlife Research Center, 2110 Miriam Circle, Bismarck, ND 58503, USA article info abstract Article history: Frugivorous birds impose significant costs on tree fruit growers through direct consumption of fruit and Received 10 March 2016 grower efforts to manage birds. -

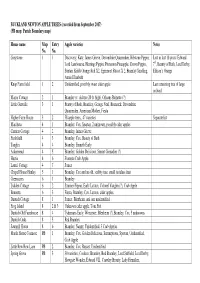

BUCKLAND NEWTON APPLE TREES (Recorded from September 2017) (PB Map: Parish Boundary Map)

BUCKLAND NEWTON APPLE TREES (recorded from September 2017) (PB map: Parish Boundary map) House name Map Entry Apple varieties Notes No. No. Greystone 1 1 Discovery, Katy, James Grieve, Devonshire Quarrenden, Ribstone Pippin, Lost in last 10 years: Edward Lord Lambourne, Herrings Pippin, Pitmaston Pineapple, Crown Pippin, 7th , Beauty of Bath, Lord Derby, Suntan, Kidds Orange Red X2, Egremont Russet X 2, Bramley Seedling, Ellison’s Orange Annie Elizabeth Knap Farm field 1 2 Unidentified, possibly sweet cider apple Last remaining tree of large orchard Manor Cottage 2 1 Bramley (v. old tree 20 ft. high), Orleans Reinette (?) Little Gunville 3 1 Beauty of Bath, Bramley, George Neal, Bismarck, Devonshire Quarrenden, American Mother, Fiesta Higher Farm House 3 2 58 apple trees,, 47 varieties Separate list Marcheta 4 1 Bramley, Cox, Spartan, 2 unknown, possibly cider apples Carriers Cottage 4 2 Bramley, James Grieve Freshfield 4 3 Bramley, Cox, Beauty of Bath Tanglin 4 4 Bramley, Emneth Early Askermead 4 5 Bramley, Golden Delicious, Sunset Grenadier (?) Hestia 4 6 Evereste Crab Apple Laurel Cottage 4 7 Sunset Chapel House Henley 5 1 Bramley, Cox and an old, scabby tree, small tasteless fruit Greenacres 6 1 Bramley Lydden Cottage 6 2 Sturmer Pippin, Early Laxton, Colonel Vaughn (?), Crab Apple Bennetts 6 3 Fiesta, Bramley, Cox, Laxton, cider apples Duntish Cottage 8 1 Sunset, Blenheim, and one unidentified Frog Island 8 2 & 3 Unknown cider apple, Tom Putt Duntish Old Farmhouse 8 4 Tydemans Early, Worcester, Blenheim (?),Bramley, Cos, 5 unknowns -

Consultation on Draft Food Growing Strategy

CONSULTATION ON DRAFT FOOD GROWING STRATEGY Report by Executive Director, Finance and Regulatory EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 15 September 2020 1 PURPOSE AND SUMMARY 1.1. Following the legislative requirements set out in Part 9 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, this report introduces Scottish Borders Council’s first ever Food Growing Strategy – ‘Cultivating Communities’ and seeks approval for consultation on the Draft Strategy. This report also sets out the process and next steps in delivering on the Strategy Action Plan, as well as associated changes to Allotment management –including new Allotment Regulations - as required by the legislation. 1.2. The Food Growing Strategy supports the Locality Plans for the region and is itself supported with the proposed creation of new policy EP17 in the Local Development Plan. 1.3 The Consultation Draft Food Growing Strategy was proposed to be brought to Executive on March 17th 2020. However due to Covid-19, this has been delayed. This paper now brings the Draft Strategy, and proposed Allotment Regulations, to Executive for approval for consultation and resourcing. 2 RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 It is recommended that the Executive Committee:- (a) Approves the Draft Strategy for Consultation (b) Approves the proposals for resourcing as set out in 9.1 (c) Approves the proposed statutory consultation on the new Allotment Regulations Executive Committee – 15 September 2020 3 BACKGROUND 3.1 Part 9 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 updates and simplifies allotments legislation, bringing it together in a single instrument, introducing new duties on local authorities to increase transparency on the actions taken to provide allotments in their area and limit waiting times. -

2017 Annual Report Bismarck Parks and Recreation District Operations

2017 Annual Report Bismarck Parks and Recreation District Operations Division 1 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Role of the Operations Division ......................................................................................................................... 3 Human Resources ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Full-Time Staff ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Seasonal Staff ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Labor Breakdown General Maintenance .................................................................................................... 8 Total Hours per Location ........................................................................................................................... 8 Total Hours per Task ................................................................................................................................ 10 Labor Breakdown Park Planner ................................................................................................................. 11 Training.......................................................................................................................................................... -

Soil Nutrient Management in Haiti, Pre-Columbus to the Present Day: Lessons for Future Agricultural Interventions Remy N Bargout and Manish N Raizada*

Bargout and Raizada Agriculture & Food Security 2013, 2:11 http://www.agricultureandfoodsecurity.com/content/2/1/11 REVIEW Open Access Soil nutrient management in Haiti, pre-Columbus to the present day: lessons for future agricultural interventions Remy N Bargout and Manish N Raizada* Abstract One major factor that has been reported to contribute to chronic poverty and malnutrition in rural Haiti is soil infertility. There has been no systematic review of past and present soil interventions in Haiti that could provide lessons for future aid efforts. We review the intrinsic factors that contribute to soil infertility in modern Haiti, along with indigenous pre-Columbian soil interventions and modern soil interventions, including farmer-derived interventions and interventions by the Haitian government and Haitian non-governmental organizations (NGOs), bilateral and multilateral agencies, foreign NGOs, and the foreign private sector. We review how agricultural soil degradation in modern Haiti is exacerbated by topology, soil type, and rainfall distribution, along with non- sustainable farming practices and poverty. Unfortunately, an ancient strategy used by the indigenous Taino people to prevent soil erosion on hillsides, namely, the practice of building conuco mounds, appears to have been forgotten. Nevertheless, modern Haitian farmers and grassroots NGOs have developed methods to reduce soil degradation. However, it appears that most foreign NGOs are not focused on agriculture, let alone soil fertility issues, despite agriculture being the major source of livelihood in rural Haiti. In terms of the types of soil interventions, major emphasis has been placed on reforestation (including fruit trees for export markets), livestock improvement, and hillside erosion control. -

Apple Pollination Groups

Flowering times of apples RHS Pollination Groups To ensure good pollination and therefore a good crop, it is essential to grow two or more different cultivars from the same Flowering Group or adjacent Flowering Groups. Some cultivars are triploid – they have sterile pollen and need two other cultivars for good pollination; therefore, always grow at least two other non- triploid cultivars with each one. Key AGM = RHS Award of Garden Merit * Incompatible with each other ** Incompatible with each other *** ‘Golden Delicious’ may be ineffective on ‘Crispin’ (syn. ‘Mutsu’) Flowering Group 1 Very early; pollinated by groups 1 & 2 ‘Gravenstein’ (triploid) ‘Lord Suffield’ ‘Manks Codlin’ ‘Red Astrachan’ ‘Stark Earliest’ (syn. ‘Scarlet Pimpernel’) ‘Vista Bella’ Flowering Group 2 Pollinated by groups 1,2 & 3 ‘Adams's Pearmain’ ‘Alkmene’ AGM (syn. ‘Early Windsor’) ‘Baker's Delicious’ ‘Beauty of Bath’ (partial tip bearer) ‘Beauty of Blackmoor’ ‘Ben's Red’ ‘Bismarck’ ‘Bolero’ (syn. ‘Tuscan’) ‘Cheddar Cross’ ‘Christmas Pearmain’ ‘Devonshire Quarrenden’ ‘Egremont Russet’ AGM ‘George Cave’ (tip bearer) ‘George Neal’ AGM ‘Golden Spire’ ‘Idared’ AGM ‘Irish Peach’ (tip bearer) ‘Kerry Pippin’ ‘Keswick Codling’ ‘Laxton's Early Crimson’ ‘Lord Lambourne’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Maidstone Favourite’ ‘Margil’ ‘Mclntosh’ ‘Red Melba’ ‘Merton Charm’ ‘Michaelmas Red’ ‘Norfolk Beauty’ ‘Owen Thomas’ ‘Reverend W. Wilks’ ‘Ribston Pippin’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Ross Nonpareil’ ‘Saint Edmund's Pippin’ AGM (partial tip bearer) ‘Striped Beefing’ ‘Warner's King’ AGM (triploid) ‘Washington’ (triploid) ‘White Transparent’ Flowering Group 3 Pollinated by groups 2, 3 & 4 ‘Acme’ ‘Alexander’ (syn. ‘Emperor Alexander’) ‘Allington Pippin’ ‘Arthur Turner’ AGM ‘Barnack Orange’ ‘Baumann's Reinette’ ‘Belle de Boskoop’ AGM (triploid) ‘Belle de Pontoise’ ‘Blenheim Orange’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Bountiful’ ‘Bowden's Seedling’ ‘Bramley's Seedling’ AGM (triploid, partial tip bearer) ‘Brownlees Russett’ ‘Charles Ross’ AGM ‘Cox's Orange Pippin’ */** ‘Crispin’ (syn. -

Growing Urban Orchards

GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS THE UPS, DOWNS AND HOW-TOS OF FRUIT TREE CARE IN THE CITY GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City by Susan Poizner Dedicated to Sherry, Lynn and all the volunteers of the Ben Nobleman Park Community Orchard. Growing Urban Orchards: The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City By Susan Poizner Illustrations: Sherry Firing Copy Editors: Jack Kirchhoff, Lynn Nicholas Design: Bungalow Publisher: Orchard People (2359434 Ontario Inc.): 107 Everden Road, Toronto, ON M6C 3K7 Canada www.urbanfruittree.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or me- chanical, including photocopying, recording or by any informa- tion storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Copyright: 2014 Orchard People (2359434 Ontario Inc.): First Edition, 2014 Published in Canada Growing Urban Orchards The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City By Susan Poizner Growing Urban Orchards The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City By Susan Poizner GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS Table of Contents Part 1: Introduction Chapter 1: Discovering Urban Orchards 3 Chapter 2: Selecting Your Site 7 Site Preparation 8 Orchard Inspiration: Walnut Way, Milwaukee, WI 10 Chapter 3: Parts of a Fruit Tree 13 Blossoms and Fruit 13 Buds and Leaves 16 Roots 18 Trunk and Bark 20 The Grafted Tree 22 Understanding Grafting: The Story of the McIntosh Apple 23 GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS Part 2: Selecting, Planting and Caring for Your Tree Chapter 4: Selecting Your Fruit Trees 25 Hardiness 26 Disease Resistance 26 Tree Size 27 Cross-Pollinating Fruit Trees 27 Self-Pollinating Fruit Trees 27 Staggering the Harvest 28 Eating, Cooking or Canning 28 Heirloom Trees 28 Orchard Inspiration: Community Orchard Research Project, Calgary, AB. -

June-12-2020-CB-Digi

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 63, No. 11 Friday, June 12, 2020 $4.00 50 Amazing ’Series Memories Drama, wild moments highlight the history of the College World Series for the past 73 years. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Editor/Collegiate Baseball MAHA, Neb. — Since there is no College World Series this Oyear because of the coronavirus pandemic, Collegiate Baseball thought it would be a good idea to remind people what a remarkable event this tournament is. So we present the 50 greatest memories He had not hit a home run all season in CWS history. long. 1. Most Dramatic Moment To End With one runner on, he hit the only Game: With two outs in the bottom of the walk-off homer to win a College World ninth in the 1996 College World Series Series in history as it barely cleared the championship game, Miami (Fla.) was on right field wall as LSU pulled off a 9-8 the cusp of winning the national title over win in the national title game. Louisiana St. with 1-run lead. 2. Greatest Championship Game: With one runner on, LSU’s Warren Southern California and Florida State Morris stepped to the plate. played the greatest College World Series He did not play for 39 games due to a championship game in history. WILD CELEBRATIONS — The College World Series in Omaha has featured fractured hamate bone in his right wrist The Trojans beat the Seminoles, 2-1 remarkable moments over the past 73 years, including plenty of dog piles to and only came back to the starting lineup celebrate national championships. -

Applied to the Buying-In Prices for Fruit and Vegetables 1 . in Annex VIII, The

24 . 6 . 89 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 177/37 COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 1822/89 of 23 June 1989 amending Regulation ( EEC) No 3587/86 fixing the conversion factors to be applied to the buying-in prices for fruit and vegetables THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES , grapes produced with a view to the obligatory distillation of wine made from table grapes ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the Management Committee for Fruit and Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 1035/72 Vegetables has not delivered an opinion within the time of 18 May 1972 on the common organization of the limit set by its chairman, market in fruit and vegetables ('), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 1 1 19/89 (2), and in particular Article HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION : 16 (4) thereof, Whereas Commission Regulation (EEC) No 3587/86 (J), Article 1 as last amended by Regulation (EEC) No 2040/88 (4), fixes the conversion factors permitting the calculation of the Regulation (EEC) No 3587/86 is hereby amended as prices at which products with characteristics different follows : from those of products used for the fixing of the basic 1 . In Annex VIII, the list of varieties of large pears is and buying-in prices are bought in ; replaced by the list set out in Annex I hereto . Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 920/89 (5) lays down quality standards for citrus fruit, apples and 2. The first indent of point (b) in Annexe IX is replaced pears ; whereas the provisions of Regulation (EEC) No by the following : 3587/86 should accordingly by adapted to those II .