NSEERS: the Consequences of America's Efforts to Secure Its Borders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final CERD Follow up Report

THE PERSISTENCE OF RACIAL AND ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE UNITED STATES A FOLLOW-UP REPORT TO THE U.N. COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION BY THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION AND THE RIGHTS WORKING GROUP JUNE 30, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Chandra Bhatnagar, staff attorney with the ACLU Human Rights Program, is the principal author of this report. Jamil Dakwar, director of the Human Rights Program, reviewed and edited drafts of the report. Nicole Kief of the ACLU Racial Justice Program also provided significant material and valuable editing assistance. Mónica Ramírez of the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project provided substantial material and reviewed sections of the report. Reggie Shuford of the Racial Justice Program; Lenora Lapidus of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project; and Michael Macleod-Ball, Jennifer Bellamy, and Joanne Lin of the ACLU Washington Legislative Office also reviewed drafts and contributed to the report, as did Ken Choe of the ACLU LGBT Project. Rachel Bloom and Nusrat Jahan Choudhary of the Racial Justice Program; Mike German and John Hardenbergh of the Washington Legislative Office; and Dan Mach of the ACLU Program on Religion and Belief all made contributions as well. Two law students, Elizabeth Joynes (Fordham Law School) and Peter Beauchamp (New York Law School), provided substantial editorial support and research assistance; Aron Cobbs from the Human Rights Program also contributed. Many ACLU affiliates made available extremely valuable material about and analyses of their state-based work, including Arizona, Arkansas, Northern California, Southern California, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Eastern Missouri, New Mexico, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and West Virginia. -

Under the Radar: Muslims Deported, Detained, and Denied on Unsubstantiated Terrorism Allegations (New York: NYU School of Law, 2011)

CHRGJ and AALDEF ABOUT THE AUTHORS The Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) at New York University School of Law was established in 2002 to bring together the law school’s teaching, research, clinical, internship, and publishing activities around issues of international human rights law. Through its litigation, advocacy, and research work, CHRGJ plays a critical role in identifying, denouncing, and fighting human rights abuses in several key areas of focus, including: Business and Human Rights; Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Caste Discrimination; Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism; Extrajudicial Executions; and Transitional Justice. Philip Alston and Ryan Goodman are the Center’s Faculty Chairs; Smita Narula and Margaret Satterthwaite are Faculty Directors; Jayne Huckerby is Research Director; and Veerle Opgenhaffen is Senior Program Director. The International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) at New York University School of Law provides high quality, professional human rights lawyering services to community-based organizations, nongovernmental human rights organizations, and intergovernmental human rights experts and bodies. The Clinic partners with groups based in the United States and abroad. Working as researchers, legal advisers, and advocacy partners, Clinic students work side-by-side with human rights advocates from around the world. The Clinic is directed by Professor Smita Narula of the NYU faculty; Amna Akbar is Senior Research Scholar and Advocacy Fellow; and Susan Hodges is Clinic Administrator. The Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF), founded in 1974, is a national organization that protects and promotes the civil rights of Asian Americans. By combining litigation, advocacy, education, and organizing, AALDEF works with Asian American communities across the country to secure human rights for all. -

Perspectives from the Dhs Frontline: Evaluating Staffing Resources and Requirements

S. Hrg. 115–159 PERSPECTIVES FROM THE DHS FRONTLINE: EVALUATING STAFFING RESOURCES AND REQUIREMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 22, 2017 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–014 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin, Chairman JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri ROB PORTMAN, Ohio THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware RAND PAUL, Kentucky JON TESTER, Montana JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming GARY C. PETERS, Michigan JOHN HOEVEN, North Dakota MAGGIE HASSAN, New Hampshire STEVE DAINES, Montana KAMALA D. HARRIS, California CHRISTOPHER R. HIXON, Staff Director GABRIELLE D’ADAMO SINGER, Chief Counsel BROOKE N. ERICSON, Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy JOSE´ J. BAUTISTA, Senior Professional Staff Member MARGARET E. DAUM, Minority Staff Director CAITLIN A. WARNER, Minority Counsel J. JACKSON EATON IV, Minority Senior Counsel HANNAH M. BERNER, Minority Investigator LAURA W. KILBRIDE, Chief Clerk BONNI E. DINERSTEIN, Hearing Clerk (II) C O N T E N T S Opening statements: -

Billing Code: 9111-97-P DEPARTMENT OF

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/20/2021 and available online at Billing Code: 9111-97-P federalregister.gov/d/2021-17779, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY 8 CFR Parts 208 and 235 [CIS No. 2692-21; DHS Docket No. USCIS-2021-0012] RIN 1615-AC67 DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Executive Office for Immigration Review 8 CFR Parts 1003, 1208, and 1235 [A.G. Order No. 5116-2021] RIN 1125-AB20 Procedures for Credible Fear Screening and Consideration of Asylum, Withholding of Removal, and CAT Protection Claims by Asylum Officers AGENCY: Executive Office for Immigration Review, Department of Justice; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security. ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. SUMMARY: The Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) (collectively, “the Departments”) are proposing to amend the regulations governing the determination of certain protection claims raised by individuals subject to expedited removal and found to have a credible fear of persecution or torture. Under the proposed rule, such individuals could have their claims for asylum, withholding of removal under section 241(b)(3) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA” or “the Act”) (“statutory withholding of removal”), or protection under the regulations issued pursuant to the legislation implementing U.S. obligations under Article 3 of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (“CAT”) initially adjudicated by an asylum officer within U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”). Such individuals who are granted relief by the asylum officer would be entitled to asylum, withholding of removal, or protection under CAT, as appropriate. -

The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance

The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance A Report from the Southern Poverty Law Center Montgomery, Alabama February 2009 The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance By Heidi BeiricH • edited By Mark Potok the southern poverty law center is a nonprofit organization that combats hate, intolerance and discrimination through education and litigation. Its Intelligence Project, which prepared this report and also produces the quarterly investigative magazine Intelligence Report, tracks the activities of hate groups and the nativist movement and monitors militia and other extremist anti- government activity. Its Teaching Tolerance project helps foster respect and understanding in the classroom. Its litigation arm files lawsuits against hate groups for the violent acts of their members. MEDIA AND GENERAL INQUIRIES Mark Potok, Editor Heidi Beirich Southern Poverty Law Center 400 Washington Ave., Montgomery, Ala. (334) 956-8200 www.splcenter.org • www.intelligencereport.org • www.splcenter.org/blog This report was prepared by the staff of the Intelligence Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Center is supported entirely by private donations. No government funds are involved. © Southern Poverty Law Center. All rights reserved. southern poverty law center Table of Contents Preface 4 The Puppeteer: John Tanton and the Nativist Movement 5 FAIR: The Lobby’s Action Arm 9 CIS: The Lobby’s ‘Independent’ Think Tank 13 NumbersUSA: The Lobby’s Grassroots Organizer 18 southern poverty law center Editor’s Note By Mark Potok Three Washington, D.C.-based immigration-restriction organizations stand at the nexus of the American nativist movement: the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), and NumbersUSA. -

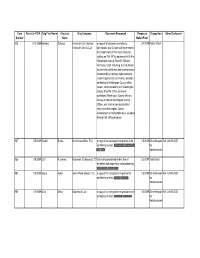

ICE FOIA Case 2009FOIA4931, Including Any Associated Communications with FPS and Including Also Any Associated E-Mail Correspondence with FPS

Case Recv'd in FOIA Orig First Name Orig Last Orig Company Document Requested Response Disposition Other Disclosure Number Name Mailed Final 805 2/13/2009 Barbara Szweda American Civil Liberties a copy of all documents related to 3/4/2009 Partial Grant Union of Utah (ACLU) Immigration and Customs Enforcement or the Department of Homeland Security signing an INA 287(g) agreement with the Washington County Sheriff’s Office in Hurricane, Utah, including, but not limited to contracts, drafts and final memoranda of understanding, training, implementation, citizen inquiries and comments, materials pertaining to Washington County officer review, communications with Washington County Sheriff’s Office, names of authorized Washington County officers, names of trained Washington County Officer, and internal communications relating to Washington County enforcement of immigration laws, including through the 287(g) program 987 1/5/2009 Garald Burns Burns Law Office, PLC a copy of the complete immigration A-file 1/5/2009 Other Reason Ref. to NRC/CIS b6 pertaining to client, n for b6 Nondisclosure 988 1/5/2009 Carl Rumanek Rumanek & Company LTD information pertaining to the time of 2/2/2009 Total Grant detention and deportation date pertaining t b6 992 1/5/2009 Joyce Asber John Wheat Gibson, P.C. a copy of the complete immigration file 1/5/2009 Other Reason Ref. to NRC/CIS pertaining to client, b6 for Nondisclosure 993 1/5/2009 Gino Mesa Attorney at Law a copy of the complete immigration record 1/5/2009 Other Reason Ref. to NRC/CIS pertaining to client, -

Petitioners, V

■ -I c r- •—v s* ; J <- L-- ^ L4 *— No. 20- >\ Supreme Court, U.S. In The FILED JAN 1 5 2021 Pankajkumar S. Patel and Jyotsnaben P. Patel,L. OFFICE OF THE CLERK Petitioners, v. United States Attorney General, Respondent. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI Mark C. Fleming IraJ. Kurzban Wilmer Cutler Pickering Counsel of Record Hale and Dorr llp Helena Tetzeli 60 State Street John P. Pratt Boston, MA 02109 Edward F. Ramos Elizabeth Montano Justin M. Baxenberg Kurzban Kurzban Joss A.Berteaud Tetzeli & Pratt P.A. Wilmer Cutler Pickering 131 Madeira Avenue Hale and Dorr llp Coral Gables, FL 33134 1875 Pennsylvania Ave. NW (305) 444-0060 Washington DC 20006 [email protected] Margaret T. Artz Thomas G. Sprankling Wilmer Cutler Pickering Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr llp Hale and Dorr llp 7 World Trade Center 2600 El Camino Real 250 Greenwich Street Suite 400 New York, NY 10007 Palo Alto, CA 94306 RECEIVED JAN 2 2 2021 QUESTIONS PRESENTED Petitioner Pankajkumar S. Patel checked a box on a Georgia driver’s license application erroneously iden tifying himself as a U.S. citizen, even though Mr. Patel was eligible for a license regardless of his citizenship. When Mr. Patel later sought to adjust his status to law ful permanent resident, a divided panel of the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) denied him relief, holding that he is inadmissible because he “falsely represented” himself as a U.S. citizen for a benefit under state law. -

Frontline Defenders Mexico ENGLISH V2.Indd

DEFENDERS BEYOND BORDERS: MIGRANT RIGHTS DEFENDERS UNDER ATTACK IN CENTRAL AMERICA, MEXICO & THE UNITED STATES September 2019 Research: Front Line Defenders, Red TDT, LIS-Justicia en Movimiento, Prami Universidad Iberoamericana Cuidad de Mexico Editorial Work & Translation: Alex Mensing Cover Photo: Erin Kilbride - Front Line Defenders Map Design: Andrea Lopez Romero Report Design: Colin Brennan Front Line Defenders, PRAMI and Red TDT express immense gratitude to the human rights defenders who took time, effort and risks to speak with the researchers of this report. The authors also thank Alex Mensing for his editorial work and translation, and Margarita Nuñez for her research, analysis and collaboration Table of Contents I. Introduction 5-11 Summary Acronyms Context II. Migrant Rights Defenders’ Work 12-15 a. On the Ground Accompaniment & Shelter Coordination b. Humanitarian Assistance c. Desert Aid & Rescue d. Human Rights Education & Community Mobilisation e. Asylum-Seeker Accompaniment & Observations at US Ports of Entryand Mexico’s Regularisation Offices and Detention Centres f. Legal Representation g. Research and Advocacy III. Risks / Threats 16-35 a. Arrest & Detention b. Deportation & Threats of Deportation c. Detention & Trial d. Defamation & Subsequent Threats e. Surveillance, Intimidation and Attacks on Shelters, Offices, and Community Gathering Spaces f. Criminal Networks, Nationalist Militias, Non-state Armed Actors IV. Final Observations 36-39 - Intergovernmental Coordination - Criminalisation of HRDs Helping Migrants Through Legal Immigration Processes - Terrorism Rhetoric - Risks of Militarisation and Increasing Border Security - Identities V. Recommendations 40-42 Migrant Rights Defenders September 2019 “In the 1990s, there were 12 Customs and Border Patrol agents in our community. Now there’s 400. The militarisation of the border went from being a background thing to the dominant issue shaping our lives. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 21- IN THE Supreme Court of the United States MOHAMMAD SHARIF KHALIL, Petitioner, v. UR JADDOU, et al., Respondents. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES CouRT OF AppEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRcuIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI KATHRYN H. BRADY Counsel of Record ALLIE J. HALLMARK FRANCHEL D. DANIEL CHARLES D. SWifT, Director CONSTITUTIONAL LAW CENTER FOR MUSLIMS IN AMERICA 100 North Central Expressway, Suite 1010 Richardson, TX 75080 (972) 914-2507 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner 305353 A (800) 274-3321 • (800) 359-6859 i QUESTION PRESENTED The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) identifies various “terrorist activities” that render a noncitizen inadmissible. 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(3)(B). The REAL ID Act of 2005 amended the INA to, among other things, add a ground of inadmissibility for receipt of “military-type training . from or on behalf of any organization that, at the time the training was received, was a terrorist organization (as defined in clause (vi)).” Id. § 1182(a) (3)(B)(i)(VIII). No other terrorism-related grounds of inadmissibility under § 1182 include the language “at the time” to describe the conduct at issue. In the early–mid 1980s, Petitioner Mohammad Sharif Khalil fought against the Soviets with the U.S.-backed and trained war-time ally known as Jamiat-i-Islami (Jamiat). Mr. Khalil disclosed his background with Jamiat and was granted asylum in 2000. In its 2019 denial of Mr. Khalil’s application to adjust status, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services claimed that beginning in the late 1980s, Jamiat qualified as an undesignated “Tier III” terrorist organization under § 1182(a)(3)(B)(vi)(III) of the INA, as amended by the PATRIOT Act of 2001. -

Racial Profiling and Lack Protections for Individuals Harmed by Programs

ABOUT RIGHTS WORKING GROUP Formed in the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, the Rights Working Group (RWG) is a national coalition of civil liberties, national security, immigrant rights and human rights organizations committed to restoring due process and human rights protections that have been eroded in the name of national security. RWG works to ensure that everyone in the United States is able to exercise their rights, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, race, national origin, religion or ethnicity. With 275 member organizations across the United States, RWG mobilizes a grassroots constituency in support of a policy advocacy agenda that demands accountability from the U.S. government for the equal protection of human rights. RWG is led by a Steering Committee, composed of leading organizations representing the key constituencies of the coalition. Steering Committee members include the American- Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee; American Civil Liberties Union, American Immigration Lawyers Association; Arab American Institute; Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services; Asian American Justice Center; Bill of Rights Defense Committee; Border Network for Human Rights; Breakthrough; Center for National Security Studies; Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles; Human Rights First; Human Rights Watch; Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights; The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights & Education Fund; Muslim Advocates; National Council of La Raza; National Immigration Forum; National Immigration Law Center; New York Immigration Coalition; One America; Open Society Policy Center; South Asian Americans Leading Together; and the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition. The full breadth of the RWG’s work can be seen at www.rightsworkinggroup.org. -

The Lasting Legacy of Exclusion

THE LASTING LEGACY OF EXCLUSION How the Law that Brought Us Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Excluded Immigrant Families & Institutionalized Racism in Our Social Support System by Elisa Minoff, Isabella Camacho-Craft, Valery Martínez, and Indivar Dutta-Gupta Center for the Study of Social Policy || Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality About CSSP CSSP is a national, non-profit policy organization that connects community action, public system reform, and policy change. We work to achieve a racially, economically, and socially just society in which all children and families thrive. To do this, we translate ideas into action, promote public policies grounded in equity, support strong and inclusive communities, and advocate with and for all children and families marginalized by public policies and institutional practices. About GCPI The Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality (GCPI) works with policymakers, researchers, practitioners, advocates, and people with lived experience to develop effective policies and practices that alleviate poverty and inequality in the United States. GCPI conducts research and analysis, develops policy and programmatic solutions, hosts convenings and events, and produces reports, briefs, and policy proposals. We develop and advance promising ideas and identify risks and harms of ineffective policies and practices, with a cross-cutting focus on racial and gender equity. The work of GCPI is conducted by two teams: the Initiative on Gender Justice and Opportunity and the Economic Security and Opportunity Initiative. The mission of GCPI’s Economic Security and Opportunity Initiative (ESOI) is to expand economic inclusion in the United States through rigorous research, analysis, and ambitious ideas to improve programs and policies. -

Blowing Off Steam Or Setting Wildfires?

University of Tulsa College of Law TU Law Digital Commons Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works 2009 The Oklahoma Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act: Blowing Off tS eam or Setting Wildfires? Elizabeth McCormick [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/fac_pub Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation 23 Geo. Immigr. L. J. 293 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles, Chapters in Books and Other Contributions to Scholarly Works by an authorized administrator of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OKLAHOMA TAXPAYER AND CITIZEN PROTECTION ACT: BLOWING OFF STEAM OR SETTING WILDFIRES? ELIZABETH MCCORMICK* ABSTRACT This article considers Oklahoma's recent experiment in immigration regulation and examines how it is that Oklahoma has found itself on the front lines of the illegal immigration debate. The article begins with a discussion of the rich history of immigration to and immigrants in Oklahoma. It then attempts to unpack the evolution of Oklahoma's illegal immigration crisis and understand the genesis and the impacts of the state's comprehensive but perhaps exaggerated response to the perceived crisis. Finally, using Oklaho- ma's experience as an example, the article argues that a "steam valve" model of immigration federalism is no longer an apt description of sub-federal immigration lawmaking. Rather than allowing states to blow off their anti-immigrant steam, this article argues that allowing individual states to enact immigration control measures locally provides a dangerous mechanism for national anti-immigrant groups to accomplish through a state-by-state lobbying effort what they have been unable to achieve at the national level.