Ushr Final for Print.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2011 Vancouver Prime Time TV Schedules 7 P.M

Spring 2011 Vancouver Prime Time TV Schedules 7 p.m. - 11 p.m. February 20 - March 12 2011 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 7 Wheel of Fortune Heartland Jeopardy! 8 Little Mosque Rick Mercer Report Marketplace NHL Hockey Dragon's Den The Nature of Things 18 to Life InSecurity The Rick Mercer Report Movie 9 Village on a Diet The Pillars of the Earth Republic of Doyle Documentary the fifth estate HNIC After Hours 10 The National The National CBUT CBC News Make the Politician Work 7 Entertainment Tonight 16:9 The Bigger Picture Simpsons Entertainment Tonight Canada Family Restaurant American Dad 8 Survivor: Redemption Simpsons House Glee Wipeout Kitchen Nightmares Island Bob's Burgers Movie 9 The Office Family Guy The Chicago Code NCIS: Los Angeles NCIS 90210 The Office Cleveland Show 10 The Office Hawaii Five-0 The Good Wife Off the Map Haven The Guard Brothers & Sisters CHAN Outsourced 7 How I Met Your Mother what's cooking America's Funniest Home The Office The Most Amazing Videos 8 Community Who do you think you Glenn Martin, DDS Extreme Makeover: Home Minute to Win It Rules of Engagement are? Out There Edition The Bachelor The Biggest Loser 9 Modern Family How I Met Your Mother Fringe The Cape Cougar Town Parks & Recreation 10 30 Rock Movie Harry's Law Parenthood The Murdoch Mysteries Mantracker The Murdoch Mysteries CKVU Perfect Couples 7 eTalk eTalk eTalk eTalk CSI W-Five Undercover Boss The Big Bang Theory The Big Bang Theory The Big Bang Theory The Big Bang Theory 8 Mr. -

Final CERD Follow up Report

THE PERSISTENCE OF RACIAL AND ETHNIC PROFILING IN THE UNITED STATES A FOLLOW-UP REPORT TO THE U.N. COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION BY THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION AND THE RIGHTS WORKING GROUP JUNE 30, 2009 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Chandra Bhatnagar, staff attorney with the ACLU Human Rights Program, is the principal author of this report. Jamil Dakwar, director of the Human Rights Program, reviewed and edited drafts of the report. Nicole Kief of the ACLU Racial Justice Program also provided significant material and valuable editing assistance. Mónica Ramírez of the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project provided substantial material and reviewed sections of the report. Reggie Shuford of the Racial Justice Program; Lenora Lapidus of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project; and Michael Macleod-Ball, Jennifer Bellamy, and Joanne Lin of the ACLU Washington Legislative Office also reviewed drafts and contributed to the report, as did Ken Choe of the ACLU LGBT Project. Rachel Bloom and Nusrat Jahan Choudhary of the Racial Justice Program; Mike German and John Hardenbergh of the Washington Legislative Office; and Dan Mach of the ACLU Program on Religion and Belief all made contributions as well. Two law students, Elizabeth Joynes (Fordham Law School) and Peter Beauchamp (New York Law School), provided substantial editorial support and research assistance; Aron Cobbs from the Human Rights Program also contributed. Many ACLU affiliates made available extremely valuable material about and analyses of their state-based work, including Arizona, Arkansas, Northern California, Southern California, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Eastern Missouri, New Mexico, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and West Virginia. -

Under the Radar: Muslims Deported, Detained, and Denied on Unsubstantiated Terrorism Allegations (New York: NYU School of Law, 2011)

CHRGJ and AALDEF ABOUT THE AUTHORS The Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) at New York University School of Law was established in 2002 to bring together the law school’s teaching, research, clinical, internship, and publishing activities around issues of international human rights law. Through its litigation, advocacy, and research work, CHRGJ plays a critical role in identifying, denouncing, and fighting human rights abuses in several key areas of focus, including: Business and Human Rights; Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Caste Discrimination; Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism; Extrajudicial Executions; and Transitional Justice. Philip Alston and Ryan Goodman are the Center’s Faculty Chairs; Smita Narula and Margaret Satterthwaite are Faculty Directors; Jayne Huckerby is Research Director; and Veerle Opgenhaffen is Senior Program Director. The International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) at New York University School of Law provides high quality, professional human rights lawyering services to community-based organizations, nongovernmental human rights organizations, and intergovernmental human rights experts and bodies. The Clinic partners with groups based in the United States and abroad. Working as researchers, legal advisers, and advocacy partners, Clinic students work side-by-side with human rights advocates from around the world. The Clinic is directed by Professor Smita Narula of the NYU faculty; Amna Akbar is Senior Research Scholar and Advocacy Fellow; and Susan Hodges is Clinic Administrator. The Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF), founded in 1974, is a national organization that protects and promotes the civil rights of Asian Americans. By combining litigation, advocacy, education, and organizing, AALDEF works with Asian American communities across the country to secure human rights for all. -

Perspectives from the Dhs Frontline: Evaluating Staffing Resources and Requirements

S. Hrg. 115–159 PERSPECTIVES FROM THE DHS FRONTLINE: EVALUATING STAFFING RESOURCES AND REQUIREMENTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 22, 2017 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 27–014 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin, Chairman JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri ROB PORTMAN, Ohio THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware RAND PAUL, Kentucky JON TESTER, Montana JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming GARY C. PETERS, Michigan JOHN HOEVEN, North Dakota MAGGIE HASSAN, New Hampshire STEVE DAINES, Montana KAMALA D. HARRIS, California CHRISTOPHER R. HIXON, Staff Director GABRIELLE D’ADAMO SINGER, Chief Counsel BROOKE N. ERICSON, Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy JOSE´ J. BAUTISTA, Senior Professional Staff Member MARGARET E. DAUM, Minority Staff Director CAITLIN A. WARNER, Minority Counsel J. JACKSON EATON IV, Minority Senior Counsel HANNAH M. BERNER, Minority Investigator LAURA W. KILBRIDE, Chief Clerk BONNI E. DINERSTEIN, Hearing Clerk (II) C O N T E N T S Opening statements: -

Billing Code: 9111-97-P DEPARTMENT OF

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 08/20/2021 and available online at Billing Code: 9111-97-P federalregister.gov/d/2021-17779, and on govinfo.gov DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY 8 CFR Parts 208 and 235 [CIS No. 2692-21; DHS Docket No. USCIS-2021-0012] RIN 1615-AC67 DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Executive Office for Immigration Review 8 CFR Parts 1003, 1208, and 1235 [A.G. Order No. 5116-2021] RIN 1125-AB20 Procedures for Credible Fear Screening and Consideration of Asylum, Withholding of Removal, and CAT Protection Claims by Asylum Officers AGENCY: Executive Office for Immigration Review, Department of Justice; U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Department of Homeland Security. ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. SUMMARY: The Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) (collectively, “the Departments”) are proposing to amend the regulations governing the determination of certain protection claims raised by individuals subject to expedited removal and found to have a credible fear of persecution or torture. Under the proposed rule, such individuals could have their claims for asylum, withholding of removal under section 241(b)(3) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA” or “the Act”) (“statutory withholding of removal”), or protection under the regulations issued pursuant to the legislation implementing U.S. obligations under Article 3 of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (“CAT”) initially adjudicated by an asylum officer within U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (“USCIS”). Such individuals who are granted relief by the asylum officer would be entitled to asylum, withholding of removal, or protection under CAT, as appropriate. -

The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance

The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance A Report from the Southern Poverty Law Center Montgomery, Alabama February 2009 The Nativist Lobby Three Faces of Intolerance By Heidi BeiricH • edited By Mark Potok the southern poverty law center is a nonprofit organization that combats hate, intolerance and discrimination through education and litigation. Its Intelligence Project, which prepared this report and also produces the quarterly investigative magazine Intelligence Report, tracks the activities of hate groups and the nativist movement and monitors militia and other extremist anti- government activity. Its Teaching Tolerance project helps foster respect and understanding in the classroom. Its litigation arm files lawsuits against hate groups for the violent acts of their members. MEDIA AND GENERAL INQUIRIES Mark Potok, Editor Heidi Beirich Southern Poverty Law Center 400 Washington Ave., Montgomery, Ala. (334) 956-8200 www.splcenter.org • www.intelligencereport.org • www.splcenter.org/blog This report was prepared by the staff of the Intelligence Project of the Southern Poverty Law Center. The Center is supported entirely by private donations. No government funds are involved. © Southern Poverty Law Center. All rights reserved. southern poverty law center Table of Contents Preface 4 The Puppeteer: John Tanton and the Nativist Movement 5 FAIR: The Lobby’s Action Arm 9 CIS: The Lobby’s ‘Independent’ Think Tank 13 NumbersUSA: The Lobby’s Grassroots Organizer 18 southern poverty law center Editor’s Note By Mark Potok Three Washington, D.C.-based immigration-restriction organizations stand at the nexus of the American nativist movement: the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), and NumbersUSA. -

Fall Tv Preview Specialties Cast Wider Nets, While Conventionals Strive to Stay on Top

THE BATTLE FOR EYEBALLS: FALL TV PREVIEW SPECIALTIES CAST WIDER NETS, WHILE CONVENTIONALS STRIVE TO STAY ON TOP IN THE RIGHT RETINA, ONE OF CORUS STIFLES SCREAM, BOWS THE NEW COMBATANTS BROADER-FACETED DUSK BRAND OF THE YEAR STEP CHANGE CCoverJul09.inddoverJul09.indd 1 77/10/09/10/09 99:55:18:55:18 AMAM SAVE THE DATE October 7 Design Exchange An exploration of cutting-edge media executions with global impact. Presenting Sponsor To book tickets call Presented by Joel Pinto at 416-408-2300 x650 For sponsorship opportunities contact Carrie Gillis at [email protected] atomic.strategyonline.ca SST.14386.Atomic.ad.inddT.14386.Atomic.ad.indd 1 77/13/09/13/09 55:30:26:30:26 PMPM CONTENTS July/August 2009 • volume 20, issue 12 4 EDITORIAL Instead of campaign, think election 10 6 UPFRONT How Canada fared in Cannes, Caramilk’s 16 secret revealed and answers to other life-altering questions 10 WHO Bud Light’s Kristen Morrow brings the bevco’s booze cruise to Canada 14 CREATIVE Pepsi and Coke take a page from the same book of warm, fuzzy feelings 16 DECONSTRUCTED Beer wars: Kokanee vs. Keith’s (people have gone to battle for lesser things) 19 FALL TV 14 Find out what the big nets have lined up, which new shows will burn out or fade away and how specialties are evolving to woo new audiences (and advertisers) 48 FORUM Will Novosedlik on the unrelenting power 19 of TV and Sukhvinder Obhi on getting inside consumers’ brains – literally 50 BACK PAGE Lowe Roche breaks down an agency’s thought process…this explains why there’s so much Coldplay in commercials ON THE COVER Our very cool (and a little creepy) cover image was brought to us by the dark minds at Dusk, the newly rebranded Corus specialty channel replacing Scream this fall. -

Canadian Canada $7 Summer 2015 Vol.17, No.3 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SUMMER 2015 VOL.17, NO.3 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA The 2015 WGC Screenwriting Awards – The Screenwriters Take The Spotlight ‘To Banff’ Or ‘Not To Banff’ The State Of Canadian Comedy Writing For Youth X Company Stephanie Morgenstern and Mark Ellis Reveal Canada’s Secret Spy School PM40011669 CTV_WGCmag_AD_flpg_final.pdf 1 2015-05-01 11:13 AM CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 17 No. 3 Summer 2015 Contents ISSN 1481-6253 Features Publication Mail Agreement Number Stephanie Morgenstern and Mark Ellis: 400-11669 Spies Who Came From The Cold 6 Publisher Maureen Parker Stephanie Morgenstern and Mark Ellis and their team of Editor Tom Villemaire screenwriters tell the story of Canada’s X Company spy [email protected] school and the kind of people who trained there. Director of Communications Li Robbins By Matthew Hays Editorial Advisory Board Denis McGrath (Chair) To Banff Or Not To Banff 12 Michael MacLennan We asked the question of Canadian Screenwriters: Susin Nielsen Is Banff worth the time and money? For some, yes, Simon Racioppa for others, not so much. If Banff isn’t for you, President Jill Golick (Central) we have some alternative suggestions. Councillors By Diane Wild Michael Amo (Atlantic) Mark Ellis (Central) The 19th Annual Dennis Heaton (Pacific) WGC Screenwriting Awards 16 Denis McGrath (Central) Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) The night just for screenwriters, a fun, feted evening, Andrew Wreggitt (Western) recognizing our best and brightest. Art Direction Studio Ours With photographs by Christina Gapic Design Studio Ours Printing Ironstone Media Writing For Youth: More Than A High School Confidential 30 Cover Photo: Christina Gapic There’s a skill required to write successfully for a young Canadian Screenwriter is audience. -

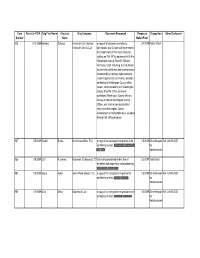

ICE FOIA Case 2009FOIA4931, Including Any Associated Communications with FPS and Including Also Any Associated E-Mail Correspondence with FPS

Case Recv'd in FOIA Orig First Name Orig Last Orig Company Document Requested Response Disposition Other Disclosure Number Name Mailed Final 805 2/13/2009 Barbara Szweda American Civil Liberties a copy of all documents related to 3/4/2009 Partial Grant Union of Utah (ACLU) Immigration and Customs Enforcement or the Department of Homeland Security signing an INA 287(g) agreement with the Washington County Sheriff’s Office in Hurricane, Utah, including, but not limited to contracts, drafts and final memoranda of understanding, training, implementation, citizen inquiries and comments, materials pertaining to Washington County officer review, communications with Washington County Sheriff’s Office, names of authorized Washington County officers, names of trained Washington County Officer, and internal communications relating to Washington County enforcement of immigration laws, including through the 287(g) program 987 1/5/2009 Garald Burns Burns Law Office, PLC a copy of the complete immigration A-file 1/5/2009 Other Reason Ref. to NRC/CIS b6 pertaining to client, n for b6 Nondisclosure 988 1/5/2009 Carl Rumanek Rumanek & Company LTD information pertaining to the time of 2/2/2009 Total Grant detention and deportation date pertaining t b6 992 1/5/2009 Joyce Asber John Wheat Gibson, P.C. a copy of the complete immigration file 1/5/2009 Other Reason Ref. to NRC/CIS pertaining to client, b6 for Nondisclosure 993 1/5/2009 Gino Mesa Attorney at Law a copy of the complete immigration record 1/5/2009 Other Reason Ref. to NRC/CIS pertaining to client, -

Pressed with Jeremyʼs Directing Skills, Which He Mentioned to Gordon Pinsent, Who Happens to Be His Father-In-Law

SEX AFTER KIDS Run Time: 105 min Canadian Distributor: IndieCan Entertainment 271 Glenholme Avenue, Suite #3 Toronto ON M6E 3C9 p. (416) 898-3456 f. (416) 658-9913 e. [email protected] Producer Contacts: Jeremy LaLonde e. [email protected] p. 416-844-6496 Jennifer Liao e. [email protected] SEX AFTER KIDS Production Notes About the Story When writer and director Jeremy LaLonde (The Untitled Work of Paul Shepard) decided he wanted to move forward with his sophomore feature film, he took a rather unconventional approach. He cast the film and then wrote the script. He says, “Itʼs far easier to write when youʼve got a voice of a character in your head, and even easier when you know exactly who is going to play that part.” And, he also adapted the old adage – write what you know. The idea for Sex After Kids was born out of his own experience. At the time, he had a newborn and a three-year-old, as he said, “Itʼs safe to say that I knew enough about this subject to realize it was pretty fertile ground and that there were probably a decent amount of people who would appreciate a comedy about the subject.” Ultimately to Jeremy, the film can mean different things for different people. “For me,” he says, “itʼs about how relationships are hard and then when you throw in uncontrollable elements it can make them impossible – but thatʼs when people grow. Itʼs about how relationships change over time and how some people have a hard time dealing with that fact.” Shannon Beckner, who plays Jules, shares the same sentiment as Jeremy, she commented, “This film is about the entirely new lives many of us unwittingly start when we bring another human being into our old ones. -

Leslie, My Name Is Evil

E1 Entertainment presents A New Real Films Production A Masculine‐Feminine Film Leslie, My Name Is Evil Directed by Reginald Harkema Producers: Jennifer Jonas and Leonard Farlinger An Official Selection of the 2009 Toronto International Film Festival, Vanguard Section www.lesliemynameisevil.com TIFF US Press Contact: Producer Contact: mPRm Public Relations New Real Films Inc. Alice Zou, [email protected] 669 Shaw St. Toronto Inter‐Continental Hotel Toronto, ON 220 Bloor Street West, Suite 325 M6G 3L8 Ph: 416‐960‐5200 Office: 416‐536‐1696 Cell 213‐359‐5775 [email protected] SYNOPSIS As the ‘60s rolled to a close, the United States was at the threshold of a turbulent time in history. President Nixon was in the White House and the U.S. was at war in Vietnam. The image of the picture‐perfect, stay‐at‐home housewife with the ideal husband and family was being threatened. Forces of change—a sexual revolution, the use of hallucinogenic drugs and a new founded challenge to authority—had crept into family rooms and dinning table conversations. Raised in a traditional Christian family, Perry leads a sheltered life, always doing what is expected of him. He has a wonderful virgin Christian girlfriend, Dorothy. He attends church with his family on Sundays and enjoys family dinners. He is following a career path that will prevent him from being drafted to fight in Vietnam. As a chemist he is book smart and company driven, but doesn’t know the harsh realities of the world. Everything he believes in is challenged the day he is chosen to be a jury member in a hippie death cult murder trial, where the defendant on trial is a strikingly beautiful woman named Leslie. -

Downloaded More Than 212,000 Times Since the Ipad's April 3Rd Launch,” the Futon Critic, 14 Apr

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature _____________________________ ______________ Nicholas Bestor Date TV to Talk About: The CW and Post-Network Television By Nicholas Bestor Master of Arts Film Studies Michele Schreiber, Ph.D. Advisor Eddy Von Mueller, Ph.D. Committee Member Karla Oeler, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date TV to Talk About: The CW and Post-Network Television By Nicholas Bestor B.A., Middlebury College, 2005 Advisor: Michele Schreiber, Ph.D. An abstract of A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies 2012 Abstract TV to Talk About: The CW and Post-Network Television By Nicholas Bestor The CW is the smallest of the American broadcast networks, but it has made the most of its marginal position by committing itself wholly to servicing a niche demographic.