Dostoevsky's Conscientious Monarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skoptsy") Sect in Russia History, Teaching, and Religious Practice Irina A

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 19 | Issue 1 Article 11 1-1-2000 The aC strati ("Skoptsy") Sect in Russia History, Teaching, and Religious Practice Irina A. Tulpe St. Petersburg State University Evgeny A. Torchinov St. Petersburg State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Tulpe, I. A., & Torchinov, E. A. (2000). Tulpe, I. A., & Torchinov, E. A. (2000). The asC trati (“Skoptsy”) sect in Russia: History, teaching, and religious practice. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 19(1), 77–87.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 19 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2000.19.1.77 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Castrati ("Skoptsy") Sect in Russia History, Teaching, and Religious Practice Irina A. Tulpe Evgeny A. Torchinov St. Petersburg State University St. Petersburg, Russia This paper outlines the history of the Russian mystical Castrati (Skoptsy) sect and suggests a brief analysis of the principal religious practice of the Castrati: their technique of ecstatic sessions (radenie). The Castrati sect was related to the sect of Christ-believers (hristovovery or hlysty) in the second part ofthe eighteenth century, and borrowed their practice of the ecstatic dances. -

Ryan Stanford Danilo Lima Shaffer Rod

PHOTO 2020 annual #2 1 DANILO LIMA SHAFFER GUSTAVO MARCASSE ROD SPARK RYAN STANFORD AND MUCH MORE! 2 3 Eugenio by Rubaudanadeu, ECCE HOMO I series, digital collage in Hahnemühle photo Rag by Ramón Tormes, 2017. Guillermo Weickert, ECCE HOMO II series, digital collage in Hahnemühle photo Rag by Ramón Tormes, 2020. FALO ART© is a annual publication. january 2020. ISSN 2675-018X version 20.01.20 Summary editing, writing and design: Filipe Chagas editorial group: Dr. Alcemar Maia Souto, Guilherme Correa e Rigle Guimarães. Danilo Lima 6 cover: photo by Ryan Stanford. (model: Sebastian, 2020) Shaffer 20 others words, to understand our privileges, Care and technique were used in the edition of this magazine. Even so, typographical errors or conceptual Editorial our differences and similarities. We are not Gustavo Marcasse 38 doubt may occur. In any case, we request the alone. communication ([email protected]) so that we can ou have a very important verify, clarify or forward the question. magazine in your hands. To have their testimonials on a magazine Rod Spark 50 This horrible past year about photography was also very relevant. came with an agenda to Editor’s note on nudity: The five artists here work exactly with the Please note that publication is about the representation reconnect humankind, to Ryan Stanford diversity of the male body. More raw or 66 of masculinity in Art. There are therefore images of make us more solidary and empathic, to male nudes, including images of male genitalia. Please Y more artistic, colorful or monochromatic, make us leave our bubble of standards approach with caution if you feel you may be offended. -

Newsletter from Moldova

· · T H E Ohio Slavic & OHIO East European · SfAlE UNIVERSITY Newsletter Volume 24, No. 4 May-June 1996 Columbus, Ohio Security and Change in the New Eastern Europe: The Perspective from Moldova By Mary Pendleton On Friday,April 12, 1996 Mary Pendle Pruth, the river separating Romania from later to Washington for Congressional ton, U.S. Ambassador to Mol the Moldovan Soviet Socialist Republic. hearings, confirmation, and swearing-in. fonner dova, delivered opening address to We could see guards and it looked just as In the meantime, I was sent to take char the conference •After Warsaw inhospitable as Romania was. Now, the ge of the embassy and, not incidentally, the the Paa: and New Cold War was over and we wondered to stay out of the line of fire. Security Cllange inthe. �m Europe.• foUowing a shortened together how life would be for her on the Shortly thereafter, on July The is 21 version of her other side. "Anything's better than Chisinau signed an agreement with remarks. 1992, Four years ago at the State Belgrade," she said. Yes, there were Moscow, a first step in a long series of De partment in early March 1992, I ran security problems In Moldova but nothing conflict resolution efforts. Since then, into a colleague with whom I had served on the order of those in former Yugos- Moldova has lived through a period often at the American Embassy In Bucharest. lavia. I wished my colleague a safe Ian- described as neither war nor peace but , I knew she was studying Serbo-Croatian ding and went about preparing for my which, in reality is much more peace than in preparation for her next assignment to next assignment which was supposed to war. -

Holy Russia in Modern Times: an Essay on Orthodoxy and Cultural Change*

HOLY RUSSIA IN MODERN TIMES: AN ESSAY ON ORTHODOXY AND CULTURAL CHANGE* Alas, ‘love thy neighbor’ offers no response to questions about the com- position of light, the nature of chemical reactions or the law of the conservation of energy. Christianity, . increasingly reduced to moral truisms . which cannot help mankind resolve the great problems of hunger, poverty, toil or the economic system, . occupies only a tiny corner in contemporary civilisation. — Vasilii Rozanov1 Chernyshevski and Pobedonostsev, the great radical and the great reac- tionary, were perhaps the only two men of the [nineteenth] century who really believed in God. Of course, an incalculable number of peasants and old women also believed in God; but they were not the makers of history and culture. Culture was made by a handful of mournful skeptics who thirsted for God simply because they had no God. — Abram Tertz [Andrei Siniavskii]2 What defines the modern age? As science and technology develop, faith in religion declines. This assumption has been shared by those who applaud and those who regret it. On the one side, for example, A. N. Wilson laments the progress of unbelief in the last two hundred years. In God’s Funeral, the title borrowed from Thomas Hardy’s dirge for ‘our myth’s oblivion’, Wilson endorses Thomas Carlyle’s doleful assessment of the threshold event of the new era: ‘What had been poured forth at the French Revolution was something rather more destructive than the vials of the Apocalypse. It was the dawning of the Modern’. As Peter Gay comments in a review, ‘Wilson leaves no doubt that the ‘‘Modern’’ with its impudent challenge to time-honoured faiths, was a disaster from start to finish’.3 On the other side, historians * I would like to thank the following for their useful comments on this essay: Peter Brown, Itsie Hull, Mark Mazower, Stephanie Sandler, Joan Scott, Richard Wortman and Reginald Zelnik. -

Faith on the Margins: Jehovah's Witnesses in the Soviet Union

FAITH ON THE MARGINS: JEHOVAH‘S WITNESSES IN THE SOVIET UNION AND POST-SOVIET RUSSIA, UKRAINE, AND MOLDOVA, 1945-2010 Emily B. Baran A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved By: Donald J. Raleigh Louise McReynolds Chad Bryant Christopher R. Browning Michael Newcity ©2011 Emily B. Baran ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT EMILY B. BARAN: Faith on the Margins: Jehovah‘s Witnesses in the Soviet Union and Post-Soviet Russia, Ukraine, and Moldova, 1945-2010 (Under the direction of Donald J. Raleigh) This dissertation examines the shifting boundaries of religious freedom and the nature of religious dissent in the postwar Soviet Union and three of its successor states through a case study of the Jehovah‘s Witnesses. The religion entered the USSR as a result of the state‘s annexation of western Ukraine, Moldavia, Transcarpathia, and the Baltic states during World War II, territories containing Witness communities. In 1949 and 1951, the state deported entire Witness communities to Siberia and arrested and harassed individual Witnesses until it legalized the religion in 1991. For the Soviet period, this dissertation charts the Soviet state‘s multifaceted approach to stamping out religion. The Witnesses‘ specific beliefs and practices offered a harsh critique of Soviet ideology and society that put them in direct conflict with the state. The non-Russian nationality of believers, as well as the organization‘s American roots, apocalyptic beliefs, ban on military service, door-to-door preaching, and denunciation of secular society challenged the state‘s goals of postwar reconstruction, creation of a cohesive Soviet society, and achievement of communism. -

Clark, Roland. "Missionaries." Sectarianism and Renewal in 1920S Romania: the Limits of Orthodoxy and Nation-Building

Clark, Roland. "Missionaries." Sectarianism and Renewal in 1920s Romania: The Limits of Orthodoxy and Nation-Building. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 125–139. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350100985.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 09:12 UTC. Copyright © Roland Clark 2021. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 7 Missionaries Evangelical groups such as Baptists, Brethren, Pentecostals and Nazarenes saw an enormous difference between themselves and other Repenters such as Seventh-Day Adventists and Bible Students. The Romanian police did not. They categorized all Repenters as criminals, together with a number of other illegal religious movements including Inochentists and Old Calendarists. Officials often confused the Bible Students with Nazarenes in particular, although both movements took pains to distance themselves from each other.1 One report from 1923 claimed that Inochentists and Adventists from Piatra village in Orhei county became over-excited when they saw two rockets in the sky that had been launched by a military unit nearby as part of a celebration. Believing that the Holy Spirit had come to earth, they attacked the gendarme station, the post office, the priest and a Jew.2 As Kapaló has shown, such reports had little basis in reality. This one was copied almost verbatim from a sensationalist newspaper article in Universul and the facts were not verified until five years later, when another report confirmed that nothing of the sort had happened.3 Many of the groups that police equated with Repenters were Russian movements such as Shtundists, Dukhobors, Molokans and Old Believers (Lipoveni). -

Eunuchs As a Narrative Device in Greek and Roman Literature

How the Eunuch Works: Eunuchs as a Narrative Device in Greek and Roman Literature Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Christopher Michael Erlinger, B.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Benjamin Acosta-Hughes, Advisor Carolina Lopez-Ruiz, Co-Advisor Anthony Kaldellis Copyright by Christopher Michael Erlinger 2016 Abstract Until now, eunuchs in early Greek and Roman literature have been ignored by classical scholars, but this dissertation rectifies that omission. In the ensuing chapters, eunuchs in literature ranging from the Classical to the early Christian period are subjected to a scholarly analysis, many of them for the first time. This comprehensive analysis reveals that eunuchs’ presence indicates a breakdown in the rules of physiognomy and, consequently, a breakdown of major categories of identity, such as ethnicity or gender. Significantly, this broader pattern manifests itself in a distinct way, within each chronological and geographical period. ii Dedication Pro Cognationibus Amicisque iii Acknowledgements Every faculty member of the Classics Department of the Ohio State University has contributed in some way to this dissertation. During my time at Ohio State University, each has furthered my intellectual growth in their own unique way, and my debt to them is immeasurable. I owe especial thanks to Tom Hawkins and my dissertation committee: Carolina Lopez-Ruiz, Anthony Kaldellis, and Benjamin Acosta-Hughes. iv Vita 2005............................................................ Webb School of California 2009............................................................ B.A. Classics, Northwestern University 2010............................................................ Postbaccalaureate Program, University of California, Los Angeles 2010 to present.......................................... -

Confessional Policies of the Russian Empire with Respect to Religious Minorities (1721–1905)* A

UDC 94+27+322 Вестник СПбГУ. Философия и конфликтология. 2018. Т. 34. Вып. 2 Confessional policies of the Russian empire with respect to religious minorities (1721–1905)* A. S. Palkin Ural Federal University, 51, ul. Lenina, Ekaterinburg, 620000, Russian Federation For citation: Palkin A. S. Confessional policies of the Russian empire with respect to religious minori- ties (1721–1905). Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Philosophy and Conflict Studies, 2018, vol. 34, issue 2, pp. 311–320. https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu17.2018.214 Russian state had multinational and polyconfessional character almost from the very begin- ning of its existence. From the 16th till the end of the 19th century it had to solve a problem of increasing religious diversity. The aim of the article is to find and analyze factors, which influ- enced relations between the state and religious minorities on the territories of the Russian em- pire. Over the course of research the following factors were found: the expansion of Russian territory and the inclusion of new peoples from the 16th to the 19th centuries, the relationship between the secular authorities and the official Church, the presence of a hierarchy of more or less harmful religious minorities, shifts that emerged when new monarchs and bureaucrats became occupied with questions of confessional management, and specific local conditions that were sharply distinct in the various parts of the empire. The article discusses duality and contradictions in religious policy of the Russian empire when two trends coexisted simultane- ously, namely the trend toward unification of religious life of the country to improve stability, on the other hand, the trend toward religious toleration to decrease tensions and increase the loyalty of religious minorities. -

Teaching Atheism and Religion in the Mari Republic, Russian Federation

FORMS AND METHODS: TEACHING ATHEISM AND RELIGION IN THE MARI REPUBLIC, RUSSIAN FEDERATION by Sonja Christine Luehrmann A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Alaina M. Lemon, Chair Professor E. Webb Keane Jr. Professor William G. Rosenberg Associate Professor Douglas T. Northrop © Sonja Christine Luehrmann All rights reserved 2009 In loving-guessing memory of my grandparents, Karl Lührmann (1892-1978) and Käte Lührmann née Emkes (1907-1997), who were, among other things, rural school teachers, and bequeathed me a riddle about what happens to people as they move between ideological systems. ii Acknowledgements On the evening of January 18, 2006, over tea between vespers and the midnight mass in honor of the feast of the Baptism of Christ, the Orthodox priest of one of Marij El’s district centers questioned the visiting German anthropologist about her views on intellectual influence. “You have probably read all three volumes of Capital, in the original?” – Some of it, I cautiously admitted. “Do you think Marx wrote it himself?” – I said that I supposed so. “And I tell you, it was satan who wrote it through his hand.” I remember making a feeble defense in the name of interpretative charity, saying that it seemed safer to assume that human authors were capable of their own errors, but could not always foresee the full consequences of their ideas. The priest seemed unimpressed, but was otherwise kind enough to sound almost apologetic when he reminded me that as a non-Orthodox Christian, I had to leave the church after the prayers for the catechumens, before the beginning of the liturgy of communion. -

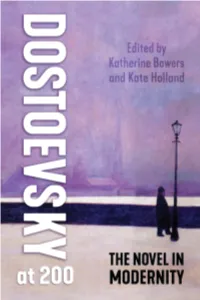

DOSTOEVSKY at 200 This Page Intentionally Left Blank Dostoevsky at 200 the Novel in Modernity

DOSTOEVSKY AT 200 This page intentionally left blank Dostoevsky at 200 The Novel in Modernity EDITED BY KATHERINE BOWERS AND KATE HOLLAND UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2021 Toronto Buffalo London utorontopress.com Printed in Canada ISBN 978-1-4875-0863-0 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-4875-3865-1 (EPUB) ISBN 978-1-4875-3864-4 (PDF) Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Title: Dostoevsky at 200 : the novel in modernity / edited by Katherine Bowers and Kate Holland. Other titles: Dostoevsky at two hundred Names: Bowers, Katherine, editor. | Holland, Kate, editor. Description: Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20210153849 | Canadiana (ebook) 2021015389X | ISBN 9781487508630 (cloth) | ISBN 9781487538651 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781487538644 (PDF) Subjects: LCSH: Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 1821–1881 – Criticism and interpretation. | LCSH: Civilization, Modern, in literature. Classification: LCC PG3328.Z6 D6285 2021 | DDC 891.73/3 – dc23 Chapter 9 includes selections from Chloë Kitzinger, “‘A novel needs a hero …’: Dostoevsky’s Realist Character-Systems.” In Mimetic Lives: Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Character in the Novel. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, forthcoming. Courtesy Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. CC-BY-NC-ND This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non- commercial No Derivative License. For permission to publish commercial versions please contact University of Toronto Press. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial support from the University of Toronto Libraries in making the open access version of this title available. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario. -

“Tsar and God” and Other Essays in Russian Cultural Semiotics Ars Rossica

“Tsar and God” And Other Essays in Russian Cultural Semiotics Ars Rossica Series Editor: David Bethea University of Wisconsin—Madison “Tsar and God” And Other Essays in Russian Cultural Semiotics Boris Uspenskij and Victor Zhivov Translated from Russian by Marcus C. Levitt, David Budgen, and Liv Bliss Edited by Marcus C. Levitt Boston 2012 The publication of this book is supported by the Mikhail Prokhorov Foundation (translation program TRANSCRIPT). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this title is available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2012 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-936235-49-0 (cloth) ISBN 978-1-61811-124-1 (electronic) Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2012 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

THE RESPONSIBILITY of the SKOPTSY ACCORDING To

1 Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores. http://www.dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/ Año: VII Número: Edición Especial Artículo no.:29 Período: Diciembre, 2019. TÍTULO: Código de sentencias penales y correccionales de 1845 sobre la responsabilidad de Skoptsy. AUTOR: 1. Cand. Ph.D. Il`ya A. Aleksandrov. RESUMEN: El artículo trata la responsabilidad de los seguidores de la doctrina skopcheskoe (castración) de acuerdo con los artículos de la Ulozhenie de castigos penales y correctivos de 1845. Se presta atención a la interpretación de las regulaciones y su aplicación, particularmente a los materiales relacionados con el juicio judicial del caso Kudrins. En el artículo se destacan las características de la doctrina Skoptsy, que permiten caracterizar las actividades de esta asociación religiosa como peligrosa para la personalidad, la sociedad y el estado. Se estudian los problemas asociados con los seguidores de esta doctrina Oskoplenie (castración). Un estudio muy detallado de estos temas se explica por el importante papel que desempeñan para la calificación correcta de las acciones criminales relevantes. PALABRAS CLAVES: Skoptsy, una secta intolerante, una herejía particularmente dañina, la Ulozhenie de castigos criminales y correctivos de 1845, el Imperio Ruso. TITLE: Code of Criminal and Correctional Sentences of 1845 on the liability of Skoptsy. 2 AUTHOR: 1. Candidate of law Il`ya A. Aleksandrov. ABSTRACT: The article deals with issues related to the responsibility of the skopcheskoe (castration) doctrine followers in accordance with the articles of the Ulozhenie of punishments criminal and corrective of 1845. Attention is paid to the interpretation of regulations and their application, particularly to materials relating to the court trial of so-called the Kudrins’ case.