Evaluation of the Sporting Chance Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRD Response Attachment

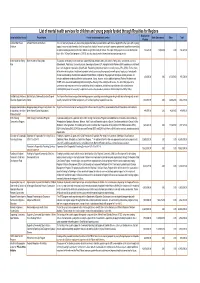

List of mental health services for children and young people funded through Royalties for Regions Royalties for List of initiatives funded Project Name A brief description of each service State Government Other Total Regions A Smart Start Great A Smart Start Great Southern The is a community based early intervention program that aims to provide families with children aged birth to four years with ongoing Southern support, resources and information. It will increase these families’ access to services to empower parents and assist them in providing an optimal learning environment for their children and get them ready for school. The scope of this project is to secure the financial 154,425.00 30,000.00 0.00 184,425.00 future of the 'A Smart Start' program to 2015/16, as it develops alternative financial and structural arrangements. Better Health for Fitzroy Better Health for Fitzroy Kids The purpose of this project is to coordinate existing WA funded child health services in the Fitzroy Valley, such that the services Kids (Allied Health, Paediatrics, Community nurses, General practitioners (GP), Aboriginal Health Workers (AHW) operate as a child health team; with integration of specialists (Allied Health, Paediatrics) and primary health (community nurses, GPs, AHWs). Further, there will be inherent integration of health and education (school) services as the proposed team will operate largely out of schools with clinical co-ordination by the Child and Adolescent Health Worker. Importantly, this project will not replace existing services, nor 400,000.00 0.00 475,500.00 875,500.00 introduce additional complexity within the existing system. -

Progress Report July 2014 – June 2015

Progress Report July 2014 – June 2015 Progress Report July 2014 – June 2015 i ii Contents Minister’s Message 2 Regional Initiatives 18 Appendices 132 Director General’s Message 3 Gascoyne 19 Appendix 1: Country Local Government Fund - Individual Local Government Signed Agreements 2014-15 133 Introduction 6 Goldfields Esperance 21 Appendix 2: Country Local Government Fund - Individual Royalties for Regions Act 2009 7 Great Southern 23 Acquitted Agreements 2014-15 136 Royalties for Regions principles 8 Kimberley 25 Appendix 3: Country Local Government Fund - Regional Groups Signed Agreements 2014-15 141 Western Australian Regional Development Trust 9 Mid West 26 Appendix 4: Country Local Government Fund Royalties for Regions funding allocation 2014-15 10 Peel 28 - Regional Groups Acquitted Agreements 2014-15 143 A snapshot of Royalties for Regions investments 12 Pilbara 30 Appendix 5: Recreational Boating Facilities Scheme State-wide Initiatives 13 South West 33 (Round 20) 150 Regional Investment Blueprints 14 Wheatbelt 35 Appendix 6: Regional Airports Development Scheme 151 Seizing the Opportunity Agriculture 15 Royalties for Regions Acknowledgements 154 Expenditure by Region 2014-15 38 Regional Telecommunications Project 17 Contact Details 155 Royalties for Regions Expenditure by Category 2014-15 65 Royalties for Regions Disbursements and Expenditure 2014-15 80 Royalties for Regions Financial Outline 2014-15 128 Progress Report July 2014 – June 2015 1 Minister’s Message Hon Terry Redman MLA Minister for Regional Development Western Australia’s -

About Frontline Education

Contents Why a move to Regional Queensland is the right one 3 A more relaxed lifestyle 3 Great affordability 3 Diverse employment opportunities beyond education 4 Education investment in Queensland 5 Frequently asked questions about teaching in Regional Queensland 6 Getting to know Queensland’s regional areas 8 The Darling Downs 9 Toowoomba 10 Central Queensland 11 Emerald 12 Gladstone 13 Rockhampton 14 Mackay 15 North Queensland 16 Townsville 17 Charters Towers 18 Mt Isa 19 Far North Queensland 20 Cairns 21 Sought-after opportunities 22 Next steps 22 About us 23 2 Why a move to Regional Queensland is the right one Queensland is the fastest growing state in Australia, largely as a result of migration from the other, colder states in the country. A warmer climate and the obvious lifestyle benefits of that are just some of the many advantages of choosing to live in Queensland. A more relaxed lifestyle Queensland in general has a strong reputation for offering a great lifestyle. This is even more the case in Regional Queensland, with its stunning uncrowded beaches and a very relaxed way of life. Great affordability Not only does Regional Queensland offer an ideal lifestyle, the cost of living is considerably lower than other areas on the Eastern Seaboard, particularly when it comes to housing in comparison to the median house prices in major metropolitan areas. Regional Queensland median house prices Far North Queensland Cairns $422,000+ North Queensland Charters Towers $86,250* Mount Isa $243,000+ Townsville $330,000+ Central Queensland Emerald $320,000* Gladstone $295,000+ Mackay $275,000* Metro median house prices Rockhampton $285,000+ Sydney $1.168 million Darling Downs South West Melbourne $918,350 Roma $225,000* Brisbane $584,778 Toowoomba $370,000+ 3 Sources +Domain House Price Report March 2020 *realestate.com.au Sept 20 Diverse employment opportunities beyond education Queensland offers a diverse range of employment opportunities with something for all skills and specialties. -

Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs Portfolio

Community Affairs Committee Examination of Budget Estimates 2006-2007 Additional Information Received VOLUME 2 HEALTH AND AGEING PORTFOLIO Outcomes: whole of portfolio and Outcomes 1, 2, 3 OCTOBER 2006 Note: Where published reports, etc. have been provided in response to questions, they have not been included in the Additional Information volume in order to conserve resources. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION RELATING TO THE EXAMINATION OF BUDGET EXPENDITURE FOR 2006-2007 Included in this volume are answers to written and oral questions taken on notice and tabled papers relating to the budget estimates hearings on 31 May and 1 June 2006 * Please note that the tabling date of 19 October 2006 is the proposed tabling date HEALTH AND AGEING PORTFOLIO Senator Quest. Whole of portfolio Vol. 2 Date tabled No. Page No. in the Senate* T2 DoHA addresses/organisation unit occupying/lease expiry 1 17.08.06 tabled at date hearing Crossin 55 Rock Eisteddfod 2 17.08.06 McLucas 118 Skin cancer national awareness 3 17.08.06 McLucas 249 Response time to questions from Parliamentary Library 4 17.08.06 Mason 9 Sick leave 5 17.08.06 McLucas 145 PBS and the 2007 Intergenerational Report 6-7 17.08.06 Ludwig 1 Expenditure on legal services 8-9 17.08.06 McLucas 90 Secretary's overseas travel 10 17.08.06 Ludwig 2 Executive coaching and/or other leadership training 11-14 14.09.06 Moore/ 192, Description of the methodology used to create and maintain 15-17 14.09.06 McLucas 250 notional allocations of Departmental funds McLucas 251 Department of Health and Ageing structure -

Notice of General Meeting

NOTICE OF GENERAL MEETING Dear Councillors, Notice is hereby given of a General Meeting of the Charters Towers Regional Council to be held Wednesday 19 February 2020 at 9.00am at the CTRC Board Room, 12 Mosman Street, Charters Towers. A Johansson Chief Executive Officer Local Government Regulation 2012, Chapter 8 Administration Part 2 Local government meetings and committees “274 Meetings in public unless otherwise resolved A meeting is open to the public unless the local government or committee has resolved that the meeting is to be closed under section 275. 275 Closed meetings (1) A local government or committee may resolve that a meeting be closed to the public if its councillors or members consider it necessary to close the meeting to discuss— (a) the appointment, dismissal or discipline of employees; or (b) industrial matters affecting employees; or (c) the local government’s budget; or (d) rating concessions; or (e) contracts proposed to be made by it; or (f) starting or defending legal proceedings involving the local government; or (g) any action to be taken by the local government under the Planning Act, including deciding applications made to it under that Act; or (h) other business for which a public discussion would be likely to prejudice the interests of the local government or someone else, or enable a person to gain a financial advantage. (2) A resolution that a meeting be closed must state the nature of the matters to be considered while the meeting is closed. (3) A local government or committee must not make a resolution (other than a procedural resolution) in a closed meeting.” GENERAL MEETING TO BE HELD WEDNESDAY, 19 FEBRUARY 2020 AT 9.00AM CTRC BOARD ROOM, 12 MOSMAN STREET, CHARTERS TOWERS MEETING AGENDA 1. -

2019-2020 Donor Yearbook

H A F 2019 | 2020 DONOR YEARBOOK H umboldt Area Foundation 2019 | 2020 Rising to the Challenge 2019 – 2020 Financials Thousands of residents of Humboldt, Trinity, Del Norte and Curry County have entrusted their $139 financial contributions to Humboldt Area Foundation. Thanks to their generosity, HAF’s grants MILLION IN ASSETS and ongoing programs will improve the quality of life in our region for years to come. BY THE NUMBERS Humboldt Area Foundation is able to do more to assist our communities thanks to the generous support of these funders. We greatly appreciate the opportunity to partner with the following organizations: • Aspen Institute • John G. Atkins Foundation Inc. 1,954 • The California Endowment GIFTS FOR • The California Wellness Foundation • BlueShield of California Foundation • Borealis Philanthropy $8 • College of the Redwoods Foundation MILLION • Community Foundation of Mendocino • Gordon Elwood Foundation • The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation • Hops in Humboldt • Humboldt State University • League of California Community Foundations • Melvin F. & Grace McLean Foundation 2,140 • Pacific Gas & Electric GRANTS FOR • Robert Woods Johnson Foundation • Silicon Valley Foundation • Patricia D. & William Smullin Foundation $6 • St. Joseph Health INVESTMENT MILLION • State Compensation Insurance Fund RETURN • Tides Foundation • True North Organizing Network • United Way – California Capital Region 2.0% • Vesper Society HAF audited financial statements and tax returns are available on our website at hafoundation.org or by request. Our Message to You I arrived at Humboldt Area Foundation and took over my position as CEO in August 2019, shortly after the start of the new fiscal year. The board, staff, and I were excited about what lie ahead: creating a community-driven strategic plan, investing in systems and infrastructure, reassessing the best ways to support our entire region, and engaging with the many generous donors devoted to this special place. -

P1547c-1552A Hon Martin Aldridge; Hon Sue Ellery

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Tuesday, 10 April 2018] p1547c-1552a Hon Martin Aldridge; Hon Sue Ellery MINISTER FOR EDUCATION AND TRAINING — SCHOOL VISITS 637. Hon Martin Aldridge to the Minister for Education and Training: I refer to regular visits undertaken by the Minister and the Parliamentary Secretary the Hon Samantha Rowe MLC to schools and educational facilities in Western Australia, and I ask: (a) from 11 March 2017, which schools or educational facilities were visited by the Minister or the Parliamentary Secretary; and (b) on what date and for what purpose did each visit occur? Hon Sue Ellery replied: Minister Facility Date Visited Purpose Emmanuel Christian Community 4/4/17 Official Opening School Hillcrest Primary School 26/4/17 ANZAC Ceremony Greenmount Primary School 27/4/17 ANZAC Ceremony Dianella Secondary College 27/4/17 Opening of Dianella Education Precinct Perth Modern School 3/5/17 Visit University of WA 26/4/17 Installation of Vice Chancellor Professor Dawn Freshwater Curtin University 29/4/17 Attend Coderdojo North Metropolitan TAFE – 2/5/17 Announcement Northbridge University of WA 9/5/17 Meet with Guild officers SciTech 9/5/17 STEM Learning Project Showcase Hale School 12/5/17 Commissioning of new Headmaster Southern River College 19/5/17 Visit Mount Hawthorn Primary School 31/5/17 Announcement University of WA 6/6/17 School of Education Graduates Prize-Giving Ceremony Kenwick School 17/6/17 Playground Opening Dianella Primary School 19/6/17 Announcement Edith Cowan University - Joondalup 23/6/17 Visit Yanchep -

Focus School List

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Action Plan – Focus School List State/ School Sector Suburb Territory ACT Ainslie School Government Braddon ACT Amaroo School Government Amaroo ACT Arawang Primary School Government Waramanga ACT Charles Conder Primary School Government Conder ACT Charnwood-Dunlop School Government Charnwood ACT Curtin Primary School Government Curtin ACT Florey Primary School Government Florey ACT Fraser Primary School Government Fraser ACT Gilmore Primary School Government Gilmore ACT Gold Creek School Government Nicholls ACT Jervis Bay Primary School Government Jervis Bay ACT Kaleen Primary School Government Kaleen ACT Kingsford Smith School Government Holt ACT Latham Primary School Government Latham ACT Lyneham Primary School Government Lyneham ACT Macgregor Primary School Government Macgregor ACT Majura Primary School Government Watson ACT Monash Primary School Government Monash ACT Namadgi School Government Kambah ACT Narrabundah Early Childhood School Government Narrabundah ACT Ngunnawal Primary School Government Ngunnawal ACT North Ainslie Primary School Government Ainslie ACT Red Hill Primary School Government Red Hill ACT Richardson Primary School Government Richardson ACT St John Vianney's Primary School Catholic Waramanga ACT Taylor Primary School Government Kambah ACT Theodore Primary School Government Theodore ACT Torrens Primary School Government Torrens ACT Wanniassa School – Senior Campus Government Wanniassa ACT Wanniassa Hills Primary School Government Wanniassa ACT Wanniassa School - -

Annual Report 2020

annualreport2020 clontarf foundation “My oldest son Tracyn is now in Year 9 so has been with Clontarf for some time. Tracyn has been on many camps, done plenty of after school activities and is loving CONTENTS his involvement with Clontarf. Who We Are and What We Do 2 Tracyn tells me often about the fun stuff you guys do but he has also told me about Chairman & CEO’s Report 3 - 16 the employment opportunities you have offered - something he intends to pursue and hopefully will accomplish by the end of the year. Roll of Honour 17 - 18 My second child Kendyl just started high school this year so his experience with Corporate Structure 19 - 22 Clontarf is still new, however he sings nothing but praise about time spent with you all in this programme. Academy Locations 23 - 26 Kendyl has some learning delays and can sometimes feel excluded, but when he is Auditor’s Report 27 - 30 doing things with the Clontarf gang, he feels a part of something. I’ve not seen my son so happy for a long time. Whilst participating with Clontarf, he is engaged and has Financial Report 31 - 57 a sense of belonging and normalcy. Partners 58 Kendyl tells me Pietje (Operations Offi cer)* has been sitting in class with him on occasions and helping him. Something I am most appreciative of. You pick my boys up for trainings, make sure they attend classes, have great after school activities, get their health checks done and the communication is awesome. Tom Clements (Academy Director)*, you’re very approachable and the other lads are great to communicate with too. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 448 952 RC 022 692 TITLE Recommendations: National Inquiry into Rural and Remote Education. INSTITUTION Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, Sydney (Australia). ISBN ISBN-0-642-26971-8 PUB DATE 2000-05-00 NOTE 119p.; For documents related to the National Inquiry into Rural and Remote Education Project, see RC 689-694. Chris Sidoti is the Human Rights Commissioner. AVAILABLE FROM Full text at Web site: http://www.hreoc.gov.au/human_rights/rural/education/index.h tml. PUB TYPE Reports Evaluative (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Education; Change Strategies; Culturally Relevant Education; Disabilities; Distance Education; Educational Cooperation; *Educational Needs; *Educational Policy; Elementary Secondary Education; *Equal Education; *Financial Support; Foreign Countries; Holistic Approach; Human Services; Indigenous Populations; Policy Formation; Professional Development; Relevance (Education); *Rural Education IDENTIFIERS Aboriginal Australians; *Australia; Social Justic3; Telecommunications Infrastructure ABSTRACT In February 1999, the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission initiated the National Inquiry into Rural and Remote Education, which investigated the provision of education for children in rural and remote Australia. The inquiry took evidence at formal public hearings in every state and territory and at less formal meetings with parents, students, educators, and community members in rural and remote areas of every state and the Northern Territory. The inquiry received 287 written and e-mailed submissions. The inquiry also commissioned a survey from Melbourne University to which 3,128 individuals responded. This report presents the inquiry findings related to rural education outcomes, responsibility for education, the policy context, and the human rights context. It offers 73 recommendations organized by five necessary features of school education: availability, accessibility, affordability, acceptability, and adaptability. -

16 Our Catholic Schools Term 1, 2010 Students from St Peter’S School, Halifax News from Our Southern & Northern Schools

Contents - Term 1, 2010 3.............Project Compassion 2010 12-13.....Focus on Secondary 4-5.........Religious life of the school 14-15.....Teaching & Learning in our Catholic Schools 6.............Parents & community 16...........Student Support Services in our Catholic Schools 7.............Environmental news 17...........News from our Northern & Southern Schools 8.............ICT in our Catholic schools 18-19.... News from our Townsville Schools 9.............Early Years Education 19...........News from our Western Schools 10-11....Focus on Primary Diocesan Education Director’s Welcome Council Update We started our school year with the wonderful news of the confirmation of the canonisation of Mother Mary MacKillop A new decade has begun and the Diocesan Education that will take place in October. Many of our schools have a Council (DEC) met for the first time this year on February 3rd. special connection to Mary MacKillop and together with our At each meeting the DEC considers ways in which Catholic Diocese, we will be celebrating and sharing her remarkable Education responds to the Bishop’s agenda by engaging in story as Australia’s very first Saint. discussion about trends, actions and ways forward. This year we are placing a special focus on our environment, keeping in line with the Bishop Michael Putney’s agenda for the last few years has official Queensland Year of Environmental Sustainability (YES 2010). Some of the fantastic focused on the following issues: environmentally sustainable projects that are taking place in our schools are featured in 1. Catholic families who have children attending non the new environmental section of this publication. -

The Consequences and Impacts of Maverick Politicians on Contemporary Australian Politics

The Consequences and Impacts of Maverick Politicians on Contemporary Australian Politics by Peter Ernest Tucker Bachelor of Business (University of Tasmania) Graduate Diploma of Management (Deakin University) Master of Town Planning (University of Tasmania) Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania December 2011 Declarations This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Peter Ernest Tucker ……………………………...………………Date…….…………… Some material published and researched by me has been included and duly acknowledged in the content of this thesis, and attached as an appendix. Peter Ernest Tucker ……………………………...………………Date…….…………… i Abstract This thesis analyses the consequences and impacts of maverick politicians on contemporary Australian politics, especially Australian political parties. The thesis uses a case study methodology to argue that maverick politicians are one manifestation of an anti-political mood currently found in the electorate; that they provide parties with a testing ground to develop leaders, although maverickism and leadership are a difficult mix of attributes to sustain; that they can have significant influence on a party’s policy formulation; and that they form strong organisational ties within the party, centred on localism.