Olly Crick Final Agreed Thesis Version III Without

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THEATRE DVD & Streaming & Performance

info / buy THEATRE DVD & Streaming & performance artfilmsdigital OVER 450 TITLES - Contemporary performance, acting and directing, Image: The Sydney Front devising, physical theatre workshops and documentaries, theatre makers and 20th century visionaries in theatre, puppets and a unique collection on asian theatre. ACTING / DIRECTING | ACTING / DEVISING | CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE WORKSHOPS | PHYSICAL / VISUAL THEATRE | VOICE & BODY | THEATRE MAKERS PUPPETRY | PRODUCTIONS | K-12 | ASIAN THEATRE COLLECTION STAGECRAFT / BACKSTAGE ACTING / DIRECTING Director and Actor: Passions, How To Use The Beyond Stanislavski - Shifting and Sliding Collaborative Directing in Process and Intimacy Stanislavski System Oyston directs Chekhov Contemporary Theatre 83’ | ALP-Direct |DVD & Streaming 68’ | PO-Stan | DVD & Streaming 110’ | PO-Chekhov |DVD & Streaming 54 mins | JK-Slid | DVD & Streaming 50’ | RMU-Working | DVD & Streaming An in depth exploration of the Peter Oyston reveals how he com- Using an abridged version of The works examine and challenge Working Forensically: complex and intimate relationship bines Stanislavski’s techniques in a Chekhov’s THE CHERRY ORCHARD, the social, temporal and gender between Actor and Director when systematic approach to provide a Oyston reveals how directors and constructs within which women A discussion between Richard working on a play-text. The core of full rehearsal process or a drama actors can apply the techniques of in particular live. They offer a Murphet (Director/Writer) and the process presented in the film course in microcosm. An invaluable Stanislavski and develop them to positive vision of the feminine Leisa Shelton (Director/Performer) involves working with physical and resource for anyone interested in suit contemporary theatre. psyche as creative, productive and about their years of collaboration (subsequent) emotional intensity the making of authentic theatre. -

Ann Lippert Acting Resume Lenz

ANN LIPPERT SAG Ht.: 5 '6 Jayne Krashin Wt: 150 Las Vegas Models (Lenz Agency) Hair: Blond cell: 702-659-0420 Eyes: Blue fax: 702-731-2008 www.lasvegasmodels.com FILM Fully Loaded Featured Dir. Shira Piven Finishing The Game Featured Dir. Justin Lin Salt the Blade and Twist the Knife Lead / Writer Dir. Ann Lippert Memoirs of an Evil Stepmother Featured (opp. Jane Lynch) Dir. Cherien Dabis Guess Who's Coming Out at Dinner Lead Dir. JD Disalvatore Reservoir Dykes & Taxi Driver Lead Dir. JD Disalvatore Half a Moment Lead Unexpected Pictures Trials of Jenny Tippett Featured Wavelength Productions TELEVISION Close To Home Co-Star Warner Brothers On Q Live Herself Talk Show- Q TV Network S Club 7 In LA Principle Los Angeles 7 Prod. It's a Miracle Co-Star Tri-Crown Productions Extreme Gong Show Principal Game Show Network THEATRE (partial list) Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All Sister Mary Ignatius Black Box Theater Los Angeles Joni and Gina's Wedding! (current) Co-writer-co creator Dir/ Ann Lippert-Hilarity Ensues Oh Sister, My Sister! Supp. / Gloria Dir. Jill Soloway (starring Jane Lynch) Dressing Room Divas Lead / Meryl Streep Steppin Out Prods - LA & Chicago The Shoemakers Supp. / Narrator Piven Theatre Workshop - Chicago Private Life of the Master Race Western Woman Chicago Shakespeare Company Two Gentlemen of Verona Lead / Julia Center Theatre - Chicago A Midsummer Nights Dream Lead / Titania Center Theatre - Chicago Sunday at the Gashouse Supp. / Sonny Projects Ensemble - LA One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest Supp. / Nurse Ratched City Playhouse - Chicago Garuda Ensemble Wild Orphans / Actors Gang - LA The Big Bang Ensemble Stage Left Theatre - Chicago Wavelength Ensemble National Touring Company Improvda Ensemble Improv Institute - Chicago Feminine Hyjinx (1st all female team) Ensemble Improv Olympic - Chicago TRAINING Acting Piven Theatre Workshop - Shira, Joyce, & Byrne Piven (8 years) - Chicago Barbara Harris, Piven Theatre Workshop - Chicago Uta Hagen, The Actors Studio, - Detroit, MI. -

S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies

S K E N È Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies 4:1 2018 Transitions Edited by Silvia Bigliazzi SKENÈ Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies Founded by Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, and Alessandro Serpieri General Editors Guido Avezzù (Executive Editor), Silvia Bigliazzi. Editorial Board Simona Brunetti, Lisanna Calvi, Nicola Pasqualicchio, Gherardo Ugolini. Editorial Staff Guido Avezzù, Silvia Bigliazzi, Lisanna Calvi, Francesco Dall’Olio, Marco Duranti, Francesco Lupi, Antonietta Provenza. Layout Editor Alex Zanutto. Advisory Board Anna Maria Belardinelli, Anton Bierl, Enoch Brater, Jean-Christophe Cavallin, Rosy Colombo, Claudia Corti, Marco De Marinis, Tobias Döring, Pavel Drábek, Paul Edmondson, Keir Douglas Elam, Ewan Fernie, Patrick Finglass, Enrico Giaccherini, Mark Griffith, Stephen Halliwell, Robert Henke, Pierre Judet de la Combe, Eric Nicholson, Guido Paduano, Franco Perrelli, Didier Plassard, Donna Shalev, Susanne Wofford. Copyright © 2018 SKENÈ Published in May 2018 All rights reserved. ISSN 2421-4353 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher. SKENÈ Theatre and Drama Studies http://www.skenejournal.it [email protected] Dir. Resp. (aut. Trib. di Verona): Guido Avezzù P.O. Box 149 c/o Mail Boxes Etc. (MBE150) – Viale Col. Galliano, 51, 37138, Verona (I) Contents Silvia Bigliazzi – Preface 5 The Editors Guido Avezzù – Collaborating with Euripides: Actors and 15 Scholars Improve the Drama Text Silvia Bigliazzi – Onstage/Offstage (Mis)Recognitions in The 39 Winter’s Tale Miscellany Angela Locatelli – Hamlet and the Android: Reading 63 Emotions in Literature Roberta Mullini – A Momaria and a Baptism: A Note on 85 Beginning and Ending in the Globe Merchant of Venice (2015) Clara Mucci – The Duchess of Malfi:When a Woman-Prince 101 Can Talk Lilla Maria Crisafulli – Felicia Hemans’s History in Drama: 123 Gender Subjectivities Revisited in The Vespers of Palermo Maria Del Sapio Garbero – Shakespeare in One Act. -

BOLOGNA 27 FEB > 1 MAR 2020

EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF THEATRE AND PERFORMANCE BOLOGNA CURATORS 27 FEB > 1 MAR 2020 Claudio Longhi, Daniele Vianello ᐅ ARENA DEL SOLE THEATRE 2020 EASTAP ASSOCIATED ARTISTS ᐅ LA SOFFITTA - DAMSLab FC Bergman CURATORS Claudio Longhi, Daniele Vianello ADVISORY BOARD Antonio Araujo (University of São Paulo) Christopher Balme (Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich) Maria João Brilhante (University of Lisbon) Chloé Déchery (University of Paris 8) Josette Féral (University of Quebec / “Sorbonne Nouvelle” University of Paris 3) Clare Finburgh Delijani (Goldsmiths – University of London) Gerardo Guccini (Alma Mater Studiorum – University of Bologna) Stefan Hulfeld (University of Vienna) Lorenzo Mango (University of Naples) Aldo Milohnić (University of Ljubljana) Elena Randi (University of Padua) Anneli Saro (University of Tartu) Diana Taylor (New York University) Gabriele Vacis (Catholic University of Sacred Heart of Milan) Piermario Vescovo (“Ca’ Foscari” University of Venice) ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Claudio Longhi - Daniele Vianello - Gerardo Guccini (Co-organizers) Silvia Cassanelli, Valentina Falorni, Licia Ferrari, Viviana Gardi, Stefania Lodi Rizzini, Giulia Maurigh, Rossella Mazzaglia, Debora Pietrobono, Martina Sottana, Francesco Vaira, Angelo Vassalli ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE Angelo Vassalli (Director) Licia Ferrari, Francesco Vaira eastap.com emiliaromagnateatro.com/en/conference-eastap [email protected] Programme 26 FEBRUARY ᐅ RIDOTTO DEI PALCHI, STORCHI THEATRE, MODENA 19.30 – 21.00 SOCIAL APERITIF 27 FEBRUARY -

MARIANGELA TEMPERA to Laugh Or Not to Laugh: Italian Parodies Of

EnterText 1.2 MARIANGELA TEMPERA To Laugh or not to Laugh: Italian Parodies of Hamlet Some years ago, at the beginning of an undergraduate course on Hamlet at the University of Ferrara, only fifteen of my eighty students admitted to having previously read the play or seen it performed. When I asked the others to write down all they knew about Hamlet and to include at least one quote from the text in their summaries, only thirty came up with a plot line that bore some resemblance to the original, but all sixty-five selected “To be or not to be, that is the question” as their quote. Hardly surprising, since this line has a life of its own, independent not only of the rest of the play but, quite often, of the rest of Hamlet’s most famous monologue. If “Shakespeare now is primarily a collage of familiar quotations,” “To be or not to be” is undoubtedly its centrepiece .1 Predictably, the monologue features prominently in Italian parodies of Hamlet. Occasionally very funny, such parodies are always worth examining because of what they can tell us about the reception of Shakespeare’s tragedy outside the theatre and the level of familiarity with Hamlet that can be assumed in the general public. Together with parodies of Romeo and Juliet and Othello, they testify to a popularity of Shakespeare in Italy that is not Tempera: To Laugh or Not to Laugh 289 EnterText 1.2 necessarily linked to any real knowledge of the dramatist’s “greatest hits”, but rather to a vague acquaintance with their basic plots and their catchiest lines. -

Crossing Boundaries Through La Commedia Dell'arte

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-08-15 Arlecchino's Journey: Crossing Boundaries Through La Commedia Dell'arte Janine Michelle Sobeck Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sobeck, Janine Michelle, "Arlecchino's Journey: Crossing Boundaries Through La Commedia Dell'arte" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 1200. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1200 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ARLECCHINO’S JOURNEY: CROSSING BOUNDARIES THROUGH LA COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE By Janine Michelle Sobeck A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Theatre and Media Arts Brigham Young University December 2007 Copyright © 2007 Janine Michelle Sobeck Al Rights Reserved ii BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Janine Michelle Sobeck This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. __________________________ ___________________________________ Date Megan Sanborn Jones, -

GS Teachers Pack2019

Teachers pack The Granny Smith Show An intimate, interactive performance piece mixing theatre, French, English and cooking! Summary The Show Questions and activities after the show The Character Set design Granny Smiths favourite activities French Various documents that can be used for an «easy» introduction to the french language Crumble à la poire – A little background information – The recipe (la recette) A few songs Masked Theatre Various documents with spoken, written and practical exercises – Mask use – Mask work – Bibliography The Granny Smith Show A comic, interactive, one woman show text and mask by Tracey Boot Role of Granny Smith Tracey Boot The Character The central character is called Granny Smith. Granny Smith is a retired, British, home economics teacher who has been living in France for a number of years. She speaks both French and English and sometimes both at the same time! She is a rather active granny who talks about her home, her likes and dislikes, her friends and activities… Question: What does Granny Smiths look like ? Activity: the students can either draw a picture or give a written account ie. french passeport / CV (name, address, physical appearance, hobbies… The Set Design: Granny Smiths house Our set is a simple but efficient interpretation of a small house: Stage right - a little living room (Petit salon) Stage left - the kitchen (cuisine) Question: What does Granny Smiths house look like ? Activity: the students can either draw a picture or give a written account Question: Who comes to Granny Smiths back door ? Answer: the post man (facteur) Granny Smiths favourite activities Granny Smith has lots of activities, she’s a very active granny! Here are some of her activities: 1) Gym (gymnastique) Granny Smith likes to keep fit she loves gym, jogging, football .. -

San a Ntonio

TEXAS San Antonio 115th Annual IAOM Conference and Expo Hyatt Regency Hotel and Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center San Antonio, Texas USA International Association of Operative Millers 10100 West 87th Street, Suite 306 Overland Park, Kansas 66212 USA www.iaom.info Improve your solutions – trust Sefar Milling and Dry Food High-precision fabrics for screening and fi ltration in the production of cereal products Filtration Solutions Headquarters Sefar AG P.O Box Kansas City CH-9410 Heiden Sefar Filtration, Inc. Switzerland 4221 NE 34th Street fi [email protected] kcfi [email protected] president s message Welcome to the 115th annual conference and expo of the International Association of Opera- tive Millers, and to beautiful downtown San Antonio. For those of you new to Texas, welcome to the great Lone Star State! The 2011 conference offers IAOM’s traditional general sessions, product showcase, and technical presentations on facilities and employee man- agement, product protection and technical operations. The Program Com- mittee has done a tremendous job this year putting together the lineup of speakers. Even though the presentations are conducted simultaneously, you’ll be able to access the presentations online following the conference. Details about how to access the information will be sent by email to all IAOM members. While in San Antonio, we offer you the opportunity to network through shared meals, educational expeditions, informal meet- ings, receptions, and Expo. Conference highlights include: • Keynote Address on the Future of -

Primavera Dei Teatri

PRIMAVERA DEI TEATRI 21st EDITION 08 > 14 OCTOBER 2020 CASTROVILLARI Performances programme THURSDAY, OCTOBER 8, 2020 8 pm | Castello Aragonese ANGELO CAMPOLO / DAF TEATRO STAY HUNGRY. Indagine di un affamato (60’) written and performed by Angelo Campolo set design Giulia Drogo assistant director Antonio Previti secretary Mariagrazia Coco produced by DAF Company and Teatro dell’Esatta Fantasia winner of the 2020 In-Box Award winner of the 2019 Nolo Milano Fringe Festival Award The filling in of a grant application concerning social issues, gives the opportunity to tell the audience the experience of Angelo, actor and director from Messina, engaged in a theatrical research in refugee shelters. Steve Jobs’ motto “Stay Hungry”, sounds like a farce when compared with the kaleidoscope of human stories, from North to South, that cross the actor’s memories. For three years his theatre training classes has been a meeting point of stories and trajectories. Without pietism, rethoric, or standpoints. Angelo takes us to his classes by the Straight, to tell the real experience of a theatre that can still be a weapon to face life. His personal daily experience of meeting and hearing the other turns into a tale on a country, Italy, which has opened and closed the doors of welcome in a schizophrenic way, leaving outside many stories, dreams, projects and human relationships that started under the cry of “Integration”. An autobiographical monologue in which victims and oppressors get confused and good and evil are separated by uncertain boundaries. All the characters are marked, each one in his own way, by a “hunger” of love and knowledge, in a time of a deep emptiness that becomes an abyss. -

2012 October Italianevent and Locationheritage Month

DATE2012 October ItalianEVENT and LOCATIONHeritage Month America in History Landing of Columbus Designs created & implemented by Constantino Brumidi (1805-1880) the Michelangelo of the United States Capitol P.O. Box 185, Medford, MA 02155-0185 [email protected] - 617-499-7955 - www.ItalianHeritageMonth.com OCTOBER ITALIAN HERITAGE MONTH COMMITTEE Giuseppe Pastorelli, Consul General, Honorary Chairman Kevin A. Caira, President Anna Quadri, Director of Public Relations Dr. Stephen F. Maio, Chairman of the Board Dr. Spencer DiScala, Historian Salvatore Bramante, Vice-President Fiscal Affairs Comm. Lino Rullo, President Emeritus James DiStefano, State President OSIA, Director Hon. Joseph V. Ferrino, Ret., Chairman Emeritus Dr. John Christoforo, Director of Education Hon. Peter W. Agnes, Jr., Chairman Emeritus THIRTEENTH ITALIAN HERITAGE MONTH NEWSLETTER This year marks the fourteenth annual observance of Italian Heritage Month. On Monday, October 1, 2012 the Italian and Italian American community will gather once again at the State House to recognize the 1999 legislation proclaim- ing October as Italian American Heritage Month. Congratulations to the 2012 Italian American Heritage Month Awards recipients Albert “Buddy” Mangini, Community Service and Jerry Leone, Middlesex County District Attorney, Law Recipient. Once again this years celebration will include a scholarship presentation to a deserving student. The committee wishes to thank the generosity of Donato Frattaroli and the Frattaroli Family for providing this years scholarship. Participating in the morning festivities will be the Boston Police Color Guard and the Coro-Dante, a chorus from the Dante Alighieri Society conducted by music director Kevin Galie. The day will conclude with lunch and socializing. The Italian American Heritage Month Committee would like to encourage all to attend this most important day. -

ISTA 2019-2020 Artist in Residency (Air) Directory

ISTA 2019-2020 Artist in Residency (AiR) Directory www.ista.co.uk “This programme Welcome to the International Schools Theatre Association really helped (ISTA) Artist in Residency (AiR) directory for 2019-2020. my students in This is your ultimate guide to ISTA’s AiR programme and offers an extensive pool of 80 internationally acclaimed artists with a huge range of unique skills who are available to visit your school throughout the year. Like last year our aim has been preparing for to launch the directory as early as possible, to ensure that teachers and schools have the information as early as possible as budgets are set towards the second quarter of 2018. It is our hope that by doing this it gives you all the time you need to make bookings with the peace of mind that the decision hasn’t been their practical rushed. One of the beautiful things about this programme is that we’ll often have an assignments. They ISTA event in a town, city or country near you. If this is the case then it’s worth waiting to see which artists are attending that event and book them accordingly. This will save you money as the flights will have already been paid gained new ways for. Usually it’s just the internal travel you’d need to provide as well as the usual accommodation and meals etc. So enjoy reading through the profiles and use the index in the back of to approach their the directory to further narrow and ease your search. These pages should have all the information you need in order to bring amazing ISTA artists to your school, but if you do need more clarification or information then please do get work and left in touch. -

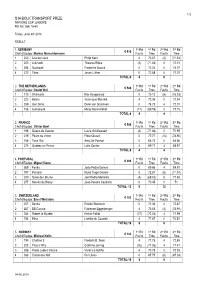

S5 Stal Erik Wiefferink Prize

1/2 S14 BOLK TRANSPORT PRIZE NATIONS CUP JUNIORS FEI Art. 264, 1m40 Friday, June 6th 2014 RESULT 1. GERMANY 1st Rd 1st Rd 2nd Rd 2nd Rd € 916 Chef d’Equipe: Markus Merschformann Faults Time Faults Time 1 200 Cracker Jack Philip Koch 4 70.67 (4) (71.53) 2 225 Calmado Theresa Ripke (4) (71.64) 0 72.15 3 296 Goshawk Frederike Staack 0 72.23 0 74.07 4 272 Tibro Jesse Luther 0 72.68 0 71.07 TOTAL:4 4 0 2. THE NETHERLANDS 1st Rd 1st Rd 2nd Rd 2nd Rd € 586 Chef d’Equipe: Roelof Bril Faults Time Faults Time 1 170 Wishkarla Kim Hoogenraat 0 73.12 (8) (76.03) 2 223 Belina Veronique Morsink 4 72.35 0 72.34 3 259 San Serai Demi van Grunsven 0 74.75 4 72.01 4 156 Camonyak Micky Morssinkhof (11) (89.59) 0 72.75 TOTAL:8 4 4 2. FRANCE 1st Rd 1st Rd 2nd Rd 2nd Rd € 586 Chef d’Equipe: Olivier Bost Faults Time Faults Time 1 196 Queen de Carene Laure Schillewaert (4) (71.86) 0 70.95 2 219 Pitaro de Virton Flore Giraud 0 77.77 (13) (78.90) 3 166 Time Out Amy De Ponnat 0 68.75 0 68.86 4 275 Quebec un Prince Lalie Saclier 4 69.17 4 68.97 TOTAL:8 4 4 4. PORTUGAL 1st Rd 1st Rd 2nd Rd 2nd Rd € 296 Chef d’Equipe: Miguel Viana Faults Time Faults Time 1 265 Fonka Joao Pedro Gomes 0 69.66 4 69.91 2 197 Pantaro Nuno Tiago Gomes 0 72.81 (8) (71.51) 3 240 Quiro des Brume Joel Pedro Monteiro (4) (69.82) 8 71.48 4 277 Nelson du Biolay Joao Pereira Coutinho 0 70.45 0 71.