Josephus' Against Apion (English Only)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Book of the KINGS Commonly Called the Third Book of The

The First Book of the KINGS Commonly Called the Third Book of the Kings INTRODUCTION [Following is the introduction to both 1 Kings and 2 Kings, which are parts of one whole.] 1. Title. The present two books of Kings were originally one, known in Hebrew as Melakim, “Kings.” In the Hebrew Bible, Kings continued undivided until the time of the printed edition of Daniel Bomberg, 1516–17. The Greek translators of the LXX, who divided the “book of Samuel” into two books, also divided the “book of Kings” into two books, and treated the four as parts 1 to 4 of “Kingdoms.” The title “Kings” indicates the contents of the books; our present first book of Kings gives the history of the Hebrew monarchs beginning with the death of David and the reign of Solomon and closing with the accession of Jehoram in Judah and Ahaziah in Israel. Second Kings begins with a continuation of the account of Ahaziah’s reign and closes with the end of the kingdom of Judah. 2. Authorship. The books of Kings are more in the nature of a compilation of selected materials brought together an editor rather than an original production from a single hand. They contain highly valuable and reliable historical material. Items drawn by inspired from early sources have been brought together and arranged into a framework following a specific pattern, with comments indicating a deep religious purpose. Many items have been taken directly or indirectly from official court or temple records. Archeological research touching many of these items has proved beyond question the striking accuracy of the accounts in Kings. -

Some Remarks on Apion1

Some remarks on Apion1 Walter Ameling Apion ʻdistinguished himself among all the opponents of the Jews by the depth of his hatred, and was therefore treated with particular bitterness by Josephusʼ.2 This is how Apion is remembered generally — an author whose works are only preserved in a shamble of fragments,3 and whose fifteen minutes of fame are due only to the openly hostile Flavius Josephus, whose last work is nowadays called contra Apionem, although this was not the original title. In this work it was Apion who got the longest and most detailed response to an individual opponent, ‘the most sustained personal invective in the treatise, and the most developed forms of ethnic vituperationʼ.4 Only the last ten years or so saw a somewhat different appreciation of the man and scholar. Apion was called ʻa multi-faceted scholar and a man who devoted his life to various studiesʼ, and was seen as someone who achieved a ʻcelebrity justly won by his brillianceʼ.5 The reaction was prompt: Apion was rather ʻa scholar gone badʼ.6 Apion was, first and foremost, a prominent intellectual, a famous figure of Graeco- Roman culture in the first century A.D. — as is attested by authors as different as Seneca and Pliny, Plutarch and Gellius. People might have criticized him, but Gellius 1 This essay started out as an attempt to write about ‘Philon and Apion’; both had lived for some years in Alexandria, might have even met there or might at least have known of each other. Both were intellectually prominent, and at least Philon was also socially prominent. -

The Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius

,.J: - f^^^- \ ^ xxV^Jr^^ EEx Libris K. OGDEN Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/atticniglitsofaul02gelliala THE ATTIC NIGHTS O P AULUS GELLIUS TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH, By THE Rev. W. B E L O E, f. s. a. XRANSLAro R OF HERODOTUS, &C. IN THREE VOLUMES. V O L. U. LONDON: I'RINTKn FO. ;. ;0HN50N. ST. p.ul's CHU^CH-VA.o. M Dec XCV. Annex PR £5-. THE ATTIC NIGHTS O F AULUS GELLIUS. BOOK VL Chap, I. The reply of Chryjippus to thoje who denied a Pro* vidence. ' ^r'HE Y who think that the world was not pro- duced on account of the Deity and of man, and deny that human affairs are governed by Providence, think * The beginning of this chapter was wanting in all the editions with which I am acquainted ; but I have reftored it from Laftantius's Epitome of his Divine Inftitutions, Chap. 29. It is a whimfical circumftance enough, that the greater part of this very Epitome ftiould have lain hid till the pre- fent century. St. Jerome, in his Catalogue of Ecclefiailical Writers, fpeaking of Laflaatius, fays, " Habemus ejus In- ftitiitionum Divinarum adverfus gentes libros feptem eitEpi- VOL. II, B tome ; « THE ATTIC NIGHTS think that they urge a 'powerful argument when they offerti that if there were a Providence there would he no evils. For nothings they affirm., can be lefs conftfi^ ent with a Providence, than that in that world, oH account of which the Deity is /aid to have created man, there fhould exijl fo great a number of cala- mities and evils. -

Three Verifications of Thiele's Date for The

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 45, No. 2, ???-???. Copyright © 2007 Andrews University Press. THREE VERIFICATIONS OF THIELE’S DATE FOR THE BEGINNING OF THE DIVIDED KINGDOM RODGER C. YOUNG St. Louis, Missouri Overview of the Work of Thiele Edwin Thiele’s work on the chronology of the divided kingdom was first published in a 1944 article that was an abridgement of his doctoral dissertation.1 His research later appeared in various journals and in his book The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, which went through three editions before Thiele’s death in 1986.2 No other chronological study dealing with the divided monarchies has found such wide acceptance among historians of the ancient Near East. The present study will show why this respect among historians is justified, particularly as regarding Thiele’s dates for the northern kingdom, while touching somewhat on the reasons that later scholars had to modify Thiele’s chronology for the southern kingdom. The breakthrough for Thiele’s chronology was that it matched various fixed dates in Assyrian history, and also helped resolve the controversy regarding other Assyrian dates, while at the same time it was consistent with all the biblical data that Thiele used to construct the chronology of the northern kingdom—but with the caveat that this was not entirely the case in his treatment of texts for the Judean kings. Of interest for the present discussion is the observation that Thiele’s dates for the northern kingdom had no substantial changes between the time of his 1944 article and the 1986 publication of the final edition of Mysterious Numbers.3 The initial skepticism that greeted Thiele’s findings has been replaced, in many quarters, by the realization that his means of establishing the dates of these kings shows a fundamental understanding of the historical issues involved, whether regarding Assyrian or Babylonian records or the traditions of the Hebrews. -

1 Kings - Keil and Delitzsch Contents Introduction

a Grace Notes course First Kings From Commentary on the Old Testament C. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch adapted for Grace Notes training by Warren Doud Grace Notes Web Site: http://www.gracenotes.info E-mail: [email protected] 1 Kings - Keil and Delitzsch Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 Kings 1 ...................................................................................................................................................... 12 1 Kings 2 ...................................................................................................................................................... 17 1 Kings 3 ...................................................................................................................................................... 24 1 Kings 4 ...................................................................................................................................................... 27 1 Kings 5 ...................................................................................................................................................... 35 1 Kings 6 ...................................................................................................................................................... 39 1 Kings 7 ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES

Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES NUMBER 7 Editorial Board Chair: Donald Mastronarde Editorial Board: Alessandro Barchiesi, Todd Hickey, Emily Mackil, Richard Martin, Robert Morstein-Marx, J. Theodore Peña, Kim Shelton California Classical Studies publishes peer-reviewed long-form scholarship with online open access and print-on-demand availability. The primary aim of the series is to disseminate basic research (editing and analysis of primary materials both textual and physical), data-heavy re- search, and highly specialized research of the kind that is either hard to place with the leading publishers in Classics or extremely expensive for libraries and individuals when produced by a leading academic publisher. In addition to promoting archaeological publications, papyrolog- ical and epigraphic studies, technical textual studies, and the like, the series will also produce selected titles of a more general profile. The startup phase of this project (2013–2017) was supported by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also in the series: Number 1: Leslie Kurke, The Traffic in Praise: Pindar and the Poetics of Social Economy, 2013 Number 2: Edward Courtney, A Commentary on the Satires of Juvenal, 2013 Number 3: Mark Griffith, Greek Satyr Play: Five Studies, 2015 Number 4: Mirjam Kotwick, Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Text of Aristotle’s Meta- physics, 2016 Number 5: Joey Williams, The Archaeology of Roman Surveillance in the Central Alentejo, Portugal, 2017 Number 6: Donald J. Mastronarde, Preliminary Studies on the Scholia to Euripides, 2017 Early Greek Alchemy, Patronage and Innovation in Late Antiquity Olivier Dufault CALIFORNIA CLASSICAL STUDIES Berkeley, California © 2019 by Olivier Dufault. -

Transformation of a Goddess by David Sugimoto

Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 263 David T. Sugimoto (ed.) Transformation of a Goddess Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite Academic Press Fribourg Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Publiziert mit freundlicher Unterstützung der PublicationSchweizerischen subsidized Akademie by theder SwissGeistes- Academy und Sozialwissenschaften of Humanities and Social Sciences InternetGesamtkatalog general aufcatalogue: Internet: Academic Press Fribourg: www.paulusedition.ch Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen: www.v-r.de Camera-readyText und Abbildungen text prepared wurden by vomMarcia Autor Bodenmann (University of Zurich). als formatierte PDF-Daten zur Verfügung gestellt. © 2014 by Academic Press Fribourg, Fribourg Switzerland © Vandenhoeck2014 by Academic & Ruprecht Press Fribourg Göttingen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen ISBN: 978-3-7278-1748-9 (Academic Press Fribourg) ISBN:ISBN: 978-3-525-54388-7978-3-7278-1749-6 (Vandenhoeck(Academic Press & Ruprecht)Fribourg) ISSN:ISBN: 1015-1850978-3-525-54389-4 (Orb. biblicus (Vandenhoeck orient.) & Ruprecht) ISSN: 1015-1850 (Orb. biblicus orient.) Contents David T. Sugimoto Preface .................................................................................................... VII List of Contributors ................................................................................ X -

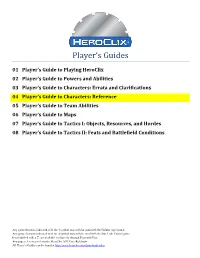

Characters – Reference Guide

Player’s Guides 01 Player’s Guide to Playing HeroClix 02 Player’s Guide to Powers and Abilities 03 Player’s Guide to Characters: Errata and Clarifications 04 Player’s Guide to Characters: Reference 05 Player’s Guide to Team Abilities 06 Player’s Guide to Maps 07 Player’s Guide to Tactics I: Objects, Resources, and Hordes 08 Player’s Guide to Tactics II: Feats and Battlefield Conditions Any game elements indicated with the † symbol may only be used with the Golden Age format. Any game elements indicated with the ‡ symbol may only be used with the Star Trek: Tactics game. Items labeled with a are available exclusively through Print-and-Play. Any page references refer to the HeroClix 2013 Core Rulebook. All Player’s Guides can be found at http://www.heroclix.com/downloads/rules Table of Contents Legion of Super Heroes† .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Avengers† ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Justice League† ................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mutations and Monsters† ................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Philostratus's Apollonius

PHILOSTRATUS’S APOLLONIUS: A CASE STUDY IN APOLOGETICS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE Andrew Mark Hagstrom A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies in the School of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Zlatko Pleše Bart Ehrman James Rives © 2016 Andrew Mark Hagstrom ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Andrew Mark Hagstrom: Philostratus’s Apollonius: A Case Study in Apologetics in the Roman Empire Under the direction of Zlatko Pleše My argument is that Philostratus drew on the Christian gospels and acts to construct a narrative in which Apollonius both resembled and transcended Jesus and the Apostles. In the first chapter, I review earlier scholarship on this question from the time of Eusebius of Caesarea to the present. In the second chapter, I explore the context in which Philostratus wrote the VA, focusing on the Severan dynasty, the Second Sophistic, and the struggle for cultural supremacy between Pagans and Christians. In the third chapter, I turn to the text of the VA and the Christian gospels and acts. I point out specific literary parallels, maintaining that some cannot be explained by shared genre. I also suggest that the association of the Egyptian god Proteus with both Philostratus’s Apollonius and Jesus/Christians is further evidence for regarding VA as a polemical response to the Christians. In my concluding chapter, I tie the several strands of my argument together to show how they collectively support my thesis. -

Classical Studies Departmental Library Booklist

Page 1 of 81 Department of Classical Studies Library Listing Call Number ISBN # Title Edition Author Author 2 Author 3 Publisher Year Quantity 0 584100051 The origins of alchemy in Graeco-Roman Egypt Jack Lindsay, 1900- London, Frederick Muller Limited 1970 0 500275866 The Mycenaeans Revised edition Lord William Taylour, London, Thames & Hudson 1990 M. Tulli Ciceronis oratio Philippica secunda : with introduction and 6280.A32P2 Stereotyped edition Marcus Tullius Cicero A. G. Peskett, ed. London, Cambridge University Press 1896 notes by A.G. Peskett A258.A75 1923 A practical introduction to Greek prose composition New Impression Thomas Kerchever Evelyn Abbott London : Longmans, Green, and Co. 1923 Gaius Valerius London : Heinemann ; New York : G. P. A6264.A2 Catullus, Tibullus, and Pervigilium Veneris F. W. Cornish 1931 Catullus, Tibullus Putnam's Sons Lucretius on matter and man. Extracts from books I, II, IV & V of the De scientific appendices AC1.E8 A. S. Cox N. A. M. Wallis London, G. Bell & Sons Ltd. 1967 rerum natura. by R.I. Gedye AM1.M76 1981 3 59810118X Museums of the world Third, revised edition Judy Benson, ed. Barbara Fischer, ed. [et al] München ; New York : K.G. Saur 1981 AM101.B87 T73 1971 0 002118343 Treasures of the British Museum: with an introduction Sir John Wolfenden London, Collins 1971 AS121.H47 Vol. 104 & Dublin : Hodges, Figgis & Co. Ltd. ; ISSN: 0018-1750 Hermathena : a Dublin University review No. CIV, Spring 1967 Trinity College Dublin 1967 105 1967 London : The Academic Press Ltd. AS121.H47 Vol. 110 - Dublin : Hodges, Figgis & Co. Ltd. ; ISSN: 0018-1750 Hermathena : a Dublin University review No. -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield. -

Microsoft Visual Basic

$ LIST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: mar 23 2020 PREVIEWS DISK: mar 25 2020 [email protected] for News, Specials and Reorders Visit WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS DUE DATE: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 23 maart 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 23 maart TEL +31 (0)492-472760 SHIPPING: ($) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 mei/juni #540 ********************************** __ 0084 Gideon Falls Stations/C TPB Vol.03 16.99 A *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* __ 0085 [M] Kick-Ass A Romita Jr #19 3.99 A ********************************** __ 0086 [M] Kick-Ass B B&W Romita Jr #19 3.99 A __ 0087 [M] Kick-Ass C Scalera #19 3.99 A DCD SALES TOOLS page 023 __ 0088 [M] Kick-Ass D Araujo #19 3.99 A __ 0023 Previews May 2020 #380 4.00 D __ 0089 [M] Kick-Ass E Blank Cvr #19 3.99 A __ 0024 Marvel Previews M EXTRA Vol.04 #34 1.25 D __ 0090 [M] Kick-Ass Dave Lizew TPB Vol.01 16.99 A __ 0025 DC Previews May 2020 EXTRA #25 0.42 D __ 0091 [M] Kick-Ass Dave Lizew TPB Vol.02 16.99 A __ 0026 Previews May 2020 Customer Or #380 0.25 D __ 0092 [M] Kick-Ass Dave Lizew TPB Vol.03 16.99 A __ 0027 Previews May 2020 Custo EXTRA #380 0.50 D __ 0093 [M] Kick-Ass Dave Lizew TPB Vol.04 16.99 A __ 0029 Previews May 2020 Retai EXTRA #380 2.08 D __ 0094 [M] Kick-Ass New Girl TPB Vol.01 16.99 A __ 0031 Game Trade Magazine #243 0.00 N __ 0095 [M] Kick-Ass New Girl TPB Vol.02 17.99 A __ 0032 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #243 0.58 N __ 0096 [M] Kick-Ass New Girl TPB Vol.03 17.99 A __ 0033 Diamond Bookshelf #32 0.12 N __ 0097 Winnebago Graveyard TPB 16.99 A IMAGE COMICS page 038 __ 0098 [M] Moonshine #18 3.99 A