Cultural Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Death in Tyre: the Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria

University of Groningen Performing Death in Tyre de Jong, Lidewijde Published in: American Journal of Archaeology DOI: 10.3764/aja.114.4.597 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): de Jong, L. (2010). Performing Death in Tyre: The Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria. American Journal of Archaeology, 114(4), 597-630. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.114.4.597 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Part 2 (Bcharre)

The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report (1) Fauna and Flora During the construction phase, fauna and flora will be not negatively impacted because of the tourism facilities will be constructed avoiding the inhabiting areas of important fauna and flora. (2) Air Pollution, Noise During the construction and operating phases air quality and noise will not be negatively impacted because that the construction will be not so large scale and the increase of tourist vehicles is not so much comparing present amount. (3) Water Quality, Solid Waste During the construction and operating phases water quality and solid waste will not be negatively impacted because that the construction will be not so large scale and the increase of tourist excreta is not so much comparing present amount. (4) Other Items During the construction and operating phases all of other items will not be negatively impacted. Part 2 (Bcharre) 2.1 EXISTING CONDITIONS Exhibits 9 and 10 present sensitive eco-system and land cover for Bcharre Qaza. ANNEX-15 The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report tem Map s Figure 9 Sensitive Ecosy Qnat Bcharre Qaza ANNEX-16 The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report Figure 10 Land Cover Map ANNEX-17 The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report 2.1.1 TOPOGRAPHY The study area could be divided into two main topographic units. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

Ptolemaic Foundations in Asia Minor and the Aegean As the Lagids’ Political Tool

ELECTRUM * Vol. 20 (2013): 57–76 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.13.004.1433 PTOLEMAIC FOUNDATIONS IN ASIA MINOR AND THE AEGEAN AS THE LAGIDS’ POLITICAL TOOL Tomasz Grabowski Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Kraków Abstract: The Ptolemaic colonisation in Asia Minor and the Aegean region was a signifi cant tool which served the politics of the dynasty that actively participated in the fi ght for hegemony over the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea basin. In order to specify the role which the settlements founded by the Lagids played in their politics, it is of considerable importance to establish as precise dating of the foundations as possible. It seems legitimate to acknowledge that Ptolemy II possessed a well-thought-out plan, which, apart from the purely strategic aspects of founding new settlements, was also heavily charged with the propaganda issues which were connected with the cult of Arsinoe II. Key words: Ptolemies, foundations, Asia Minor, Aegean. Settlement of new cities was a signifi cant tool used by the Hellenistic kings to achieve various goals: political and economic. The process of colonisation was begun by Alex- ander the Great, who settled several cities which were named Alexandrias after him. The process was successfully continued by the diadochs, and subsequently by the follow- ing rulers of the monarchies which emerged after the demise of Alexander’s state. The new settlements were established not only by the representatives of the most powerful dynasties: the Seleucids, the Ptolemies and the Antigonids, but also by the rulers of the smaller states. The kings of Pergamum of the Attalid dynasty were considerably active in this fi eld, but the rulers of Bithynia, Pontus and Cappadocia were also successful in this process.1 Very few regions of the time remained beyond the colonisation activity of the Hellenistic kings. -

New Jurassic Amber Outcrops from Lebanon Youssef Nohra, Dany Azar, Raymond Gèze, Sibelle Maksoud, Antoine El-Samrani, Vincent Perrichot

New Jurassic amber outcrops from Lebanon Youssef Nohra, Dany Azar, Raymond Gèze, Sibelle Maksoud, Antoine El-Samrani, Vincent Perrichot To cite this version: Youssef Nohra, Dany Azar, Raymond Gèze, Sibelle Maksoud, Antoine El-Samrani, et al.. New Jurassic amber outcrops from Lebanon. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews, Brill, 2013, 6, pp.27-51. 10.1163/18749836-06021056. insu-00844560 HAL Id: insu-00844560 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-00844560 Submitted on 15 Jul 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. TAR Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 6 (2013) 27–51 brill.com/tar New Jurassic amber outcrops from Lebanon Youssef Nohra1,2,3, Dany Azar1,*, Raymond Gèze1, Sibelle Maksoud1, Antoine El-Samrani1,2 and Vincent Perrichot3 1Lebanese University, Faculty of Sciences II, Department of Natural Sciences, Fanar – Matn PO box 26110217, Lebanon e-mail: [email protected] 2Lebanese University, Doctoral School of Sciences and Technology – PRASE, Hadath, Lebanon 3Geosciences Rennes (UMR CNRS 6118), Université de Rennes 1, Campus de Beaulieu, building 15, 263, avenue du General-Leclerc, 35042 Rennes cedex, France *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] Received on October 1, 2012. -

Layout CAZA AAKAR.Indd

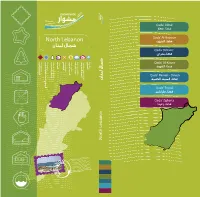

Qada’ Akkar North Lebanon Qada’ Al-Batroun Qada’ Bcharre Monuments Recreation Hotels Restaurants Handicrafts Bed & Breakfast Furnished Apartments Natural Attractions Beaches Qada’ Al-Koura Qada’ Minieh - Dinieh Qada’ Tripoli Qada’ Zgharta North Lebanon Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Akkar 1 QɵY AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG A’aidamoun 4-27 ¿ƒeó«Y Al-Bireh 5-27 √ô«ÑdG Al-Sahleh 6-27 á∏¡°ùdG A’andaqet 7-28 â≤æY A’arqa 8-28 ÉbôY Danbo 9-29 ƒÑfO Deir Jenine 10-29 ø«æL ôjO Fnaideq 11-29 ¥ó«æa Haizouq 12-30 ¥hõ«M Kfarnoun 13-30 ¿ƒfôØc Mounjez 14-31 õéæe Qounia 15-31 É«æb Akroum 15-32 ΩhôcCG Al-Daghli 16-32 »∏ZódG Sheikh Znad 17-33 OÉfR ï«°T Al-Qoubayat 18-33 äÉ«Ñ≤dG Qlaya’at 19-34 äÉ©«∏b Berqayel 20-34 πjÉbôH Halba 21-35 ÉÑ∏M Rahbeh 22-35 ¬ÑMQ Zouk Hadara 23-36 √QGóM ¥hR Sheikh Taba 24-36 ÉHÉW ï«°T Akkar Al-A’atiqa 25-37 á≤«à©dG QɵY Minyara 26-37 √QÉ«æe Qada’ Al-Batroun 69 ¿hôàÑdG AÉ°†b Map 40 á£jôîdG Kouba 42-66 ÉHƒc Bajdarfel 43-66 πaQóéH Wajh Al-Hajar 44-67 ôéëdG ¬Lh Hamat 45-67 äÉeÉM Bcha’aleh 56-68 ¬∏©°ûH Kour (or Kour Al-Jundi) 47-69 (…óæédG Qƒc hCG) Qƒc Sghar 48-69 Qɨ°U Mar Mama 49-70 ÉeÉe QÉe Racha 50-70 É°TGQ Kfifan 51-70 ¿ÉØ«Øc Jran 52-71 ¿GôL Ram 53-72 ΩGQ Smar Jbeil 54-72 π«ÑL Qɪ°S Rachana 55-73 ÉfÉ°TGQ Kfar Helda 56-74 Gó∏MôØc Kfour Al-Arabi 57-74 »Hô©dG QƒØc Hardine 58-75 øjOôM Ras Nhash 59-75 ¢TÉëf ¢SGQ Al-Batroun 60-76 ¿hôàÑdG Tannourine 62-78 øjQƒæJ Douma 64-77 ÉehO Assia 65-79 É«°UCG Qada’ Bcharre 81 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 82 á£jôîdG Beqa’a Kafra 84-97 GôØc ´É≤H Hasroun 85-98 ¿hô°üM Bcharre 86-97 …ô°ûH Al-Diman 88-99 ¿ÉªjódG Hadath -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

Stakeholder Engagement Plan 9 October 2018 CEPF Grant 108784

Stakeholder Engagement Plan 9 October 2018 CEPF Grant 108784 Friends of Nature CONSERVING LEBANON ENDEMIC FLORA THROUGH COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT Also serving as Stakeholder Engagement Plan for CEPF Grant 108497 Université Saint Joseph CONSERVER ET VALORISER LE PATRIMOINE BOTANIQUE UNIQUE DU LIBAN Orontes Valley and Levantine Mountains Grant Summary 1. Grantee organization: The Friends of Nature 2. Grant title: CONSERVING LEBANON ENDEMIC FLORA THROUGH COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT, AND CONSERVER ET VALORISER LE PATRIMOINE BOTANIQUE UNIQUE DU LIBAN 3. Grant number : CEPF-108784 & 108497 4. Grant amount (US dollars): 154,860 + 135,035 = 289,895 US$ 5. Proposed dates of grant : October 2018 – October 2020 6. Countries or territories where project will be undertaken: Orontes Valley and Levantine Mountains 7. Date of preparation of this document : 9 October 2018 8. Introduction: The two projects address the conservation of 7 priority sites in 3 KBAs where critically endangered floral species and endemic plants of restricted distribution ranges occur. The type of activities vary from one site to the other, and call for different approaches. § Bcharri – Makmel region : the project will explore the feasibility of conservation and the study of conservation measures through a community participatory approach. An action plan and a management plan will be prepared within the framework of this project for the eventual creation of a micro-reserve or other innovative forms of conservation measures; however, no restrictions are foreseen within the project mandate. § Kneisseh summit : the project will explore the feasibility of conservation and the study of conservation measures through a community participatory approach. An action plan and a management plan will be prepared within the framework of this project for the eventual creation of a micro-reserve or other innovative forms of conservation measures; however, no restrictions are foreseen within the project mandate. -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 73 (1988) 15–18 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt Gmbh, Bonn

EDITH HALL WHEN DID THE TROJANS TURN INTO PHRYGIANS? ALCAEUS 42.15 aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 73 (1988) 15–18 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 15 WHEN DID THE TROJANS TURN INTO PHRYGIANS? ALCAEUS 42.15 The Greek tragedians reformulated the myths inherited from the epic cycle in the light of the distinctively 5th-century antithesis between Hellene and barbarian. But in the case of the Trojans the most significant step in the process of their "barbarisation" was their acquisition of a new name, "Phryg- ians".1) In the Iliad, of course, the Phrygians are important allies of Troy, but geographically and politically distinct from them (B 862-3, G 184-90, K 431, P 719). The force of the distinction is made even plainer by the composer of the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, which may date from as early as the 7th century,2) where the poet introduces as an example of the goddess's power the story of her seduction of Anchises. She came to him in his Trojan home, pre- tending to be a mortal, daugter of famous Otreus, the ruler of all Phrygia (111-112). But then she immediately explained why they could converse with- out any problem (113-116); I know both your language and my own well, for a Trojan nurse brought me up in my palace: she took me from my dear mother and reared me when I was a little child. And that is why I also know your language well. So the Trojans and Phrygians are quite distinct, politically, geographically, and linguistically. -

Lebanon’S National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan

Lebanon’s National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan Republic of Lebanon Ministry of Environment BACKGROUND INFORMATION The Revision/Updating of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) of Lebanon was conducted using funds from: The Global Environment Facility (GEF) 1818 H Street, NW, Mail Stop P4-400 Washington, DC 20433 USA Tel: (202) 473-0508 Fax: (202) 522-3240/3245 Web: www.thegef.org Project title: Lebanon: Biodiversity - Enabling Activity for the Revision/Updating of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) and Preparation of the 5th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and Undertaking Clearing House Mechanism (CHM) Activities (GFL-2328-2716-4C37) Focal Point: Ms. Lara Samaha CBD Focal Point Head of Department of Ecosystems Ministry of Environment Assistant: Ms. Nada R Ghanem Managing Partner: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) GEF Biodiversity, Land Degradation and Biosafety Unit Division of Environmental Policy Implementation (DEPI) UNEP Nairobi, Kenya P.O.Box: 30552 - 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Web: www.unep.org Executing Partner: Ministry of Environment – Lebanon Department of Ecosystems Lazarieh Center, 8th floor P.O Box: 11-2727 Beirut, Lebanon Tel: +961 1 976555 Fax: +961 1 976535 Web: www.moe.gov.lb Sub-Contracted Partner: Earth Link and Advanced Resources Development (ELARD) Amaret Chalhoub - Zalka Highway Fallas Building, 2nd Floor Tel: +961 1 888305 Fax: +961 896793 Web: www.elard-group.com Authors: Mr. Ricardo Khoury Ms. Nathalie Antoun Ms. Nayla Abou Habib Contributors: All stakeholders listed under Appendices C and D of this report have contributed to its preparation. Dr. Carla Khater, Dr. Manal Nader, and Dr. -

The Cedars of God Is One of the Last Vestiges of the Extensive Forests of the Cedars of Lebanon That Thrived Across Mount Lebanon in Ancient Times

The Unique Experience! The Cedars of God is one of the last vestiges of the extensive forests of the Cedars of Lebanon that thrived across Mount Lebanon in ancient times. Their timber was exploited by the Phoenicians, the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians. The wood was prized by Egyptians for shipbuilding; the Ottoman Empire also used the cedars in railway construction. Haret Hreik | Hadi Nasrallah Blvd. | Hoteit Bldg. 1st Floor | Beirut, Lebanon Phone: 961 1 55 15 66 Mobile: 961 76 63 53 93 www.elajouztravel.com Ehden Ehden is a mountainous town situated in the heart of the northern mountains of Lebanon and on the southwestern slopes of Mount Makmal in the Mount Lebanon Range. Its residents are the people of Zgharta, as it is within the Zgharta District. Becharreh Bsharri is a town at an altitude of about 1,500 m (4,900 ft) in the Kadisha Valley in northern Lebanon. It is located in the Bsharri District of the North Governorate. Bsharri is the town of the only remaining Original Cedars of Lebanon, and is the birthplace of the famous poet, painter and sculptor Khalil Gibran who now has a museum in the town to honor him. Haret Hreik | Hadi Nasrallah Blvd. | Hoteit Bldg. 1st Floor | Beirut, Lebanon Phone: 961 1 55 15 66 Mobile: 961 76 63 53 93 www.elajouztravel.com Gibran Khalil Gibran Museum The Gibran Museum, formerly the Monastery of Mar Sarkis, is a biographical museum in Bsharri, Lebanon, 120 kilometres from Beirut. It is dedicated to the Lebanese artist, writer and philosopher Khalil Gibran. -

What Happened to the Galatian Christians? Paul's Legacy in Southern Galatia

Acta Theologica 2014 Suppl 19: 1-17 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v33i2S.1 ISSN 1015-8758 © UV/UFS <http://www.ufs.ac.za/ActaTheologica> Cilliers Breytenbach WHAT HAPPENED TO THE GALATIAN CHRISTIANS? PAUL’S LEGACY IN SOUTHERN GALATIA ABSTRACT Paul’s Letter to the Galatians points to the influence of his missionary attempts in Galatia. By reconstructing the missionary journeys of Paul and his company in Asia Minor the author argues once again for the south Galatian hypothesis, according to which the apostle travelled through the south of the province of Galatia, i.e. southern Pisidia and Lycaonia, and never entered the region of Galatia proper in the north of the province. Supporting material comes from the epigraphic evidence of the apostle’s name in the first four centuries. Nowhere else in the world of early Christianity the name Παῦλος was used with such a high frequency as in those regions where the apostle founded the first congregations in the south of the province Galatia and in the Phrygian-Galatian borderland. 1. INTRODUCTION Even though Barnabas and Paul were sent by the church of Antioch on the Orontes to the province Syria-Cilicia to spread the gospel on Cyprus and they then went to Asia Minor,1 it was only Paul who revisited Lycaonia (cf. Acts 16:1-5; 18:23). The epigraphical material referred to here, will illustrate that more than anyone else, Paul left his mark on Lycaonian Christianity.2 From the scant evidence available, it is clear that the Pauline letters and 1 Cf.