The Distribution of Troad Granite Columns As Evidence for Reconstructing the Management of Their Production Patrizio Pensabene, Javier Á

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiple Reuse of Imported Marble Pedestals at Caesarea Maritima in Israel

Multiple Reuse of Imported Marble Pedestals at Caesarea Maritima in Israel Burrell, Barbara Source / Izvornik: ASMOSIA XI, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone, Proceedings of the XI International Conference of ASMOSIA, 2018, 117 - 122 Conference paper / Rad u zborniku Publication status / Verzija rada: Published version / Objavljena verzija rada (izdavačev PDF) https://doi.org/10.31534/XI.asmosia.2015/01.10 Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:123:846795 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-07 Repository / Repozitorij: FCEAG Repository - Repository of the Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy, University of Split ASMOSIA PROCEEDINGS: ASMOSIA I, N. HERZ, M. WAELKENS (eds.): Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade, Dordrecht/Boston/London,1988. e n ASMOSIA II, M. WAELKENS, N. HERZ, L. MOENS (eds.): o t Ancient Stones: Quarrying, Trade and Provenance – S Interdisciplinary Studies on Stones and Stone Technology in t Europe and Near East from the Prehistoric to the Early n Christian Period, Leuven 1992. e i ASMOSIA III, Y. MANIATIS, N. HERZ, Y. BASIAKOS (eds.): c The Study of Marble and Other Stones Used in Antiquity, n London 1995. A ASMOSIA IV, M. SCHVOERER (ed.): Archéomatéiaux – n Marbres et Autres Roches. Actes de la IVème Conférence o Internationale de l’Association pour l’Étude des Marbres et s Autres Roches Utilisés dans le Passé, Bordeaux-Talence 1999. e i d ASMOSIA V, J. HERRMANN, N. HERZ, R. NEWMAN (eds.): u ASMOSIA 5, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone – t Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference of the S Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in y Antiquity, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, June 1998, London r 2002. -

Performing Death in Tyre: the Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria

University of Groningen Performing Death in Tyre de Jong, Lidewijde Published in: American Journal of Archaeology DOI: 10.3764/aja.114.4.597 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2010 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): de Jong, L. (2010). Performing Death in Tyre: The Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria. American Journal of Archaeology, 114(4), 597-630. https://doi.org/10.3764/aja.114.4.597 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

The Client Community Nicolspdf III 2 Status Client

The Client Community NicolsPDF_III_2 Status Client Province Date No. Nomen Cognomen ? Aquae Sabaudiae Narbonensis 200 680 Smerius Masuetus ? Eburodunum Germ sup 150 292 Flavius Camillus ? Lepcis Afr proc 60 876 Rufus ? Lepcis Afr proc 60 877 Ignotus CA ? Reii Narbonensis 150 759 Ignotus AJ chec Auzia Mauretania 200 26 Aelius Longinus chec Sufetula Afr proc 732 check check city Verona Italia x 138 474 Nonius M. f. Mucianus citz ...enacates ? Pannonia 100 332 Glitius P. f. Atilius citz Abella Italia i 120 404 Marcius Plaetorius citz Abellinum Italia i 200 59 Antonius Rufinus citz Abellinum Italia i 225 183 Caesius T.f. Anthianus citz Abellinum Italia i 175 217 Claudius Frontinus citz Abellinum Italia i 175 218 Claudius Saethida citz Abellinum Italia i 175 219 Claudius Saethida citz Abellinum Italia i 200 278 Egnatius C. f. Certus citz Acinipo Baetica 225 378 Junius L. f. Terentianus citz Acinipo Baetica 200 422 Marius M. f. Fronto citz Acinipo Baetica 200 608 Servilius Q. f. Lupus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 126 277 Eggius L. f. Ambibulus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 150 468 Neratius C. f. Proculus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 161 509 Otacilius L. f. Rufus citz Aeclanum Italia ii 240 705 Calventius L f Corl...sinus? citz Aeclanum Italia ii 150 717 Maximus? citz Aeclanum Italia ii 150 795 Ignotus BF citz Aenona Dalmatia -1 615 Silius P. f. citz Aenona Dalmatia 23 678 Volusius L. f. Saturninus citz Aequicoli Italia iv 225 389 Livius Q. f. Velenius citz Aesernia Italia iv 150 1 Abullius Dexter citz Aesernia Italia iv -25 68 Appuleius Sex f citz Aesernia Italia iv 150 262 Decrius C. -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Ptolemaic Foundations in Asia Minor and the Aegean As the Lagids’ Political Tool

ELECTRUM * Vol. 20 (2013): 57–76 doi: 10.4467/20800909EL.13.004.1433 PTOLEMAIC FOUNDATIONS IN ASIA MINOR AND THE AEGEAN AS THE LAGIDS’ POLITICAL TOOL Tomasz Grabowski Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Kraków Abstract: The Ptolemaic colonisation in Asia Minor and the Aegean region was a signifi cant tool which served the politics of the dynasty that actively participated in the fi ght for hegemony over the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea basin. In order to specify the role which the settlements founded by the Lagids played in their politics, it is of considerable importance to establish as precise dating of the foundations as possible. It seems legitimate to acknowledge that Ptolemy II possessed a well-thought-out plan, which, apart from the purely strategic aspects of founding new settlements, was also heavily charged with the propaganda issues which were connected with the cult of Arsinoe II. Key words: Ptolemies, foundations, Asia Minor, Aegean. Settlement of new cities was a signifi cant tool used by the Hellenistic kings to achieve various goals: political and economic. The process of colonisation was begun by Alex- ander the Great, who settled several cities which were named Alexandrias after him. The process was successfully continued by the diadochs, and subsequently by the follow- ing rulers of the monarchies which emerged after the demise of Alexander’s state. The new settlements were established not only by the representatives of the most powerful dynasties: the Seleucids, the Ptolemies and the Antigonids, but also by the rulers of the smaller states. The kings of Pergamum of the Attalid dynasty were considerably active in this fi eld, but the rulers of Bithynia, Pontus and Cappadocia were also successful in this process.1 Very few regions of the time remained beyond the colonisation activity of the Hellenistic kings. -

The Expansion of Christianity: a Gazetteer of Its First Three Centuries

THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY SUPPLEMENTS TO VIGILIAE CHRISTIANAE Formerly Philosophia Patrum TEXTS AND STUDIES OF EARLY CHRISTIAN LIFE AND LANGUAGE EDITORS J. DEN BOEFT — J. VAN OORT — W.L. PETERSEN D.T. RUNIA — C. SCHOLTEN — J.C.M. VAN WINDEN VOLUME LXIX THE EXPANSION OF CHRISTIANITY A GAZETTEER OF ITS FIRST THREE CENTURIES BY RODERIC L. MULLEN BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2004 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mullen, Roderic L. The expansion of Christianity : a gazetteer of its first three centuries / Roderic L. Mullen. p. cm. — (Supplements to Vigiliae Christianae, ISSN 0920-623X ; v. 69) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-13135-3 (alk. paper) 1. Church history—Primitive and early church, ca. 30-600. I. Title. II. Series. BR165.M96 2003 270.1—dc22 2003065171 ISSN 0920-623X ISBN 90 04 13135 3 © Copyright 2004 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands For Anya This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................ ix Introduction ................................................................................ 1 PART ONE CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES IN ASIA BEFORE 325 C.E. Palestine ..................................................................................... -

Issue 24 Autumn 2019

News from Herculaneum and the 8th Herculaneum Congress - Bob Fowler p.2 Bronze statue of Hyperspectral Imaging -Kilian Fleischer p.3 dancer found in 1756 between the A New Theological Work by Philodemus - Marzia D’Angelo p.5 portico and the A New Updated Version of Usener’s Glossarium Epicureum - Claudio Vegara p.7 pond of the Villa Retrospective Styles in Roman Artistic Culture - Daniel Healey p.8 of Papyri. MANN News from Professor Brent Seales and his Research Team - Christy Chapman p.10 The Friends Visit to the Getty Exhibition - Roger Macfarlane p.11 Officina Director lectures at Brigham Young University - Roger Macfarlane p.12 herculaneum archaeology herculaneum Review: Buried by Vesuvius - Bob Fowler p.13 Preview: Herculaneum & the House of the Bicentenary - Bob Fowler p.14 the newsletter of the Herculaneum Society - Issue 24 Autumn 2019 Society of the Herculaneum the newsletter Report from Silchester - Professor Mike Fulford p.14 News from Herculaneum The 8th Herculaneum Congress Hyperspectral imaging – a new technique for reading unrolled Herculanean papyri Dr. Kilian Fleischer, head of the DFG-project Philodemus’ History of the Academy, University of Würzburg. Bob Fowler, Chairman of Trustees 11–14 June 2020 In early July I was able to meet with Director Fran- The next Congress—the eighth in the vener- It rarely happens that a classicist’s or papyrologist’s work attracts attention beyond the scholarly commu- cesco Sirano at Herculaneum while I was conduct- able series—offers the usual mix of familiar and nity. For the most part, the media are not interested in new readings or reconstructions of a papyrus. -

Cultural Background

Cultural Background Funerary Patterns in Lebanon—From the Bronze Age to the Roman Period By Signe Krag 2 Hellenistic Cities in the Levant By Eva Mortensen 8 Hellenistic and Roman Sarcophagi in the Levant By Philip Ebeling 12 Maron and the Maronites By Niels Bargfeldt 19 1 Agora nr. 8 2011 Funerary Patterns in Lebanon—From the Bronze Age to the Roman Period By Signe Krag During the Bronze Age inhumation burials were the Photo: Signe Krag common practice in Lebanon. The evidence is very limited, but it suggests that several types of burials were used at the same time, namely jar burials (with inhumed infants and small children), rock-cut tombs, pit graves, cist graves and hypogea with chambers and possible sarcophagi. The burial gifts seem to have been placed in the graves according to the sex of the deceased, as men are often buried with weapons and women are buried with domes- tic objects and jewellery. Furthermore, luxury items are placed in some of the graves, a fact which sug- gests the existence of a society with marked social differences. At Sidon we find evidence for the prac- tice of animal sacrifice, and ovens that are placed at Fig. 1: The sarcophagus of Ahiram depicting mourning women. the graves suggest a belief in the afterlife of the deceased. On the sarcophagus of Ahiram from Byblos are depictions of mourning women which could tell us how the deceased was mourned. The evidence comes mainly from Beirut, Sidon and Byblos. During the Iron Age both inhumation and cremation burials were in use. -

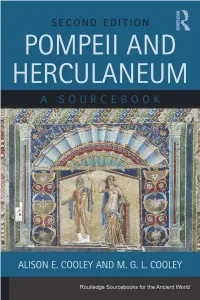

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period Ryan

Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period by Ryan Anthony Boehm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Emily Mackil, Chair Professor Erich Gruen Professor Mark Griffith Spring 2011 Copyright © Ryan Anthony Boehm, 2011 ABSTRACT SYNOIKISM, URBANIZATION, AND EMPIRE IN THE EARLY HELLENISTIC PERIOD by Ryan Anthony Boehm Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Professor Emily Mackil, Chair This dissertation, entitled “Synoikism, Urbanization, and Empire in the Early Hellenistic Period,” seeks to present a new approach to understanding the dynamic interaction between imperial powers and cities following the Macedonian conquest of Greece and Asia Minor. Rather than constructing a political narrative of the period, I focus on the role of reshaping urban centers and regional landscapes in the creation of empire in Greece and western Asia Minor. This period was marked by the rapid creation of new cities, major settlement and demographic shifts, and the reorganization, consolidation, or destruction of existing settlements and the urbanization of previously under- exploited regions. I analyze the complexities of this phenomenon across four frameworks: shifting settlement patterns, the regional and royal economy, civic religion, and the articulation of a new order in architectural and urban space. The introduction poses the central problem of the interrelationship between urbanization and imperial control and sets out the methodology of my dissertation. After briefly reviewing and critiquing previous approaches to this topic, which have focused mainly on creating catalogues, I point to the gains that can be made by shifting the focus to social and economic structures and asking more specific interpretive questions. -

Aus: Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 73 (1988) 15–18 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt Gmbh, Bonn

EDITH HALL WHEN DID THE TROJANS TURN INTO PHRYGIANS? ALCAEUS 42.15 aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 73 (1988) 15–18 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 15 WHEN DID THE TROJANS TURN INTO PHRYGIANS? ALCAEUS 42.15 The Greek tragedians reformulated the myths inherited from the epic cycle in the light of the distinctively 5th-century antithesis between Hellene and barbarian. But in the case of the Trojans the most significant step in the process of their "barbarisation" was their acquisition of a new name, "Phryg- ians".1) In the Iliad, of course, the Phrygians are important allies of Troy, but geographically and politically distinct from them (B 862-3, G 184-90, K 431, P 719). The force of the distinction is made even plainer by the composer of the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, which may date from as early as the 7th century,2) where the poet introduces as an example of the goddess's power the story of her seduction of Anchises. She came to him in his Trojan home, pre- tending to be a mortal, daugter of famous Otreus, the ruler of all Phrygia (111-112). But then she immediately explained why they could converse with- out any problem (113-116); I know both your language and my own well, for a Trojan nurse brought me up in my palace: she took me from my dear mother and reared me when I was a little child. And that is why I also know your language well. So the Trojans and Phrygians are quite distinct, politically, geographically, and linguistically.