Project Deliverable: D07.1 Case Study Report: Abou Ali River Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 2 (Bcharre)

The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report (1) Fauna and Flora During the construction phase, fauna and flora will be not negatively impacted because of the tourism facilities will be constructed avoiding the inhabiting areas of important fauna and flora. (2) Air Pollution, Noise During the construction and operating phases air quality and noise will not be negatively impacted because that the construction will be not so large scale and the increase of tourist vehicles is not so much comparing present amount. (3) Water Quality, Solid Waste During the construction and operating phases water quality and solid waste will not be negatively impacted because that the construction will be not so large scale and the increase of tourist excreta is not so much comparing present amount. (4) Other Items During the construction and operating phases all of other items will not be negatively impacted. Part 2 (Bcharre) 2.1 EXISTING CONDITIONS Exhibits 9 and 10 present sensitive eco-system and land cover for Bcharre Qaza. ANNEX-15 The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report tem Map s Figure 9 Sensitive Ecosy Qnat Bcharre Qaza ANNEX-16 The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report Figure 10 Land Cover Map ANNEX-17 The Study on the Integrated Tourism Development Plan in the Republic of Lebanon Final Report Vol. 3 Feasibility Study Report 2.1.1 TOPOGRAPHY The study area could be divided into two main topographic units. -

A Main Document V202

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: TELEVISION NEWS AND THE STATE IN LEBANON Jad P. Melki, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Dissertation directed by: Professor Susan D. Moeller College of Journalism This dissertation studies the relationship between television news and the state in Lebanon. It utilizes and reworks New Institutionalism theory by adding aspects of Mitchell’s state effect and other concepts devised from Carey and Foucault. The study starts with a macro-level analysis outlining the major cultural, economic and political factors that influenced the evolution of television news in that country. It then moves to a mezzo-level analysis of the institutional arrangements, routines and practices that dominated the news production process. Finally, it zooms in to a micro-level analysis of the final product of Lebanese broadcast news, focusing on the newscast, its rundown and scripts and the smaller elements that make up the television news story. The study concludes that the highly fragmented Lebanese society generated a similarly fragmented and deeply divided political/economic elite, which used its resources and access to the news media to solidify its status and, by doing so, recreated and confirmed the politico-sectarian divide in this country. In this vicious cycle, the institutionalized and instrumentalized television news played the role of mediator between the elites and their fragmented constituents, and simultaneously bolstered the political and economic power of the former while keeping the latter tightly held in their grip. The hard work and values of the individual journalist were systematically channeled through this powerful institutional mechanism and redirected to serve the top of the hierarchy. -

Zgharta Caza

Roads and Employment Project Environmental and Social Management Plan Zgharta Caza Final Associated Consulting Engineers 1|P a g e Roads and Employment Project Environmental and Social Management Plan Zgharta Caza TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................2 List of Tables ..........................................................................................................................6 List of Figures .........................................................................................................................7 List of Acronyms ....................................................................................................................8 Executive Summary – Non-Technical Summary .........................................................................9 19 ................................................................................................... ملخص تنفيذي - موجز غير تقني 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 28 1.1 Project Background ............................................................................................... 28 1.2 Project Rationale ................................................................................................... 28 1.3 Report Objectives .................................................................................................. 29 1.4 Methodology ....................................................................................................... -

Baalbek Hermel Zahleh Jbayl Aakar Koura Metn Batroun West Bekaa Zgharta Kesrouane Rachaiya Miniyeh-Danniyeh Bcharreh Baabda Aale

305 307308 Borhaniya - Rehwaniyeh Borj el Aarab HakourMazraatKarm el Aasfourel Ghatas Sbagha Shaqdouf Aakkar 309 El Aayoun Fadeliyeh Hamediyeh Zouq el Hosniye Jebrayel old Tekrit New Tekrit 332ZouqDeir El DalloumMqachrine Ilat Ain Yaaqoub Aakkar El Aatqa Er Rouaime Moh El Aabdé Dahr Aayas El Qantara Tikrit Beit Daoud El Aabde 326 Zouq el Hbalsa Ein Elsafa - Akum Mseitbeh 302 306310 Zouk Haddara Bezbina Wadi Hanna Saqraja - Ein Eltannur 303 Mar Touma Bqerzla Boustane Aartoussi 317 347 Western Zeita Al-Qusayr Nahr El Bared El318 Mahammara Rahbe Sawadiya Kalidiyeh Bhannine 316 El Khirbe El Houaich Memnaa 336 Bebnine Ouadi Ej jamous Majdala Tashea Qloud ElEl Baqie Mbar kiye Mrah Ech Chaab A a k a r Hmaire Haouchariye 34°30'0"N 338 Qanafez 337 Hariqa Abu Juri BEKKA INFORMALEr Rihaniye TENTEDBaddouaa El Hmaira SETTLEMENTS Bajaa Saissouq Jouar El Hachich En Nabi Kzaiber Mrah esh Shmis Mazraat Et Talle Qarqaf Berkayel Masriyeh Hamam El Minié Er Raouda Chane Mrah El Dalil Qasr El Minie El Kroum El Qraiyat Beit es Semmaqa Mrah Ez Zakbe Diyabiyeh Dinbou El Qorne Fnaydek Mrah el Arab Al Quasir 341 Beit el Haouch Berqayel Khraibe Fnaideq Fissane 339 Beit Ayoub El Minieh - Plot 256 Bzal Mishmish Hosh Morshed Samaan 340 Aayoun El Ghezlane Mrah El Ain Salhat El Ma 343 Beit Younes En Nabi Khaled Shayahat Ech Cheikh Maarouf Habchit Kouakh El Minieh - Plots: 1797 1796 1798 1799 Jdeidet El Qaitaa Khirbit Ej Jord En Nabi Youchaa Souaisse 342 Sfainet el Qaitaa Jawz Karm El Akhras Haouch Es Saiyad AaliHosh Elsayed Ali Deir Aamar Hrar Aalaiqa Mrah Qamar ed Dine -

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918)

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) by Melanie Tanielian A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Beshara Doumani Professor Saba Mahmood Professor Margaret L. Anderson Professor Keith D. Watenpaugh Fall 2012 The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) © Copyright 2012, Melanie Tanielian All Rights Reserved Abstract The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) By Melanie Tanielian History University of California, Berkeley Professor Beshara Doumani, Chair World War I, no doubt, was a pivotal event in the history of the Middle East, as it marked the transition from empires to nation states. Taking Beirut and Mount Lebanon as a case study, the dissertation focuses on the experience of Ottoman civilians on the homefront and exposes the paradoxes of the Great War, in its totalizing and transformative nature. Focusing on the causes and symptoms of what locals have coined the ‘war of famine’ as well as on international and local relief efforts, the dissertation demonstrates how wartime privations fragmented the citizenry, turning neighbor against neighbor and brother against brother, and at the same time enabled social and administrative changes that resulted in the consolidation and strengthening of bureaucratic hierarchies and patron-client relationships. This dissertation is a detailed analysis of socio-economic challenges that the war posed for Ottoman subjects, focusing primarily on the distorting effects of food shortages, disease, wartime requisitioning, confiscations and conscriptions on everyday life as well as on the efforts of the local municipality and civil society organizations to provision and care for civilians. -

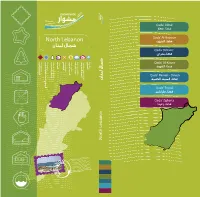

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON North Governorate, Tripoli, Batroun, Bcharreh, El Koura, El Minieh-Dennieh, Zgharta Districts (T+5)

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON North Governorate, Tripoli, Batroun, Bcharreh, El Koura, El Minieh-Dennieh, Zgharta Districts (T+5) Distribution of the Registered Syrian Refugees at the Cadastral Level As of 31 January 2015 Trablous Ez-Zahrieh Zouq Bhannine Rihaniyet-Miniye 2,610 3,769 8 Trablous El Hadid Tripoli + 5 Districts Trablous Er-Remmaneh 531 Total No. of Household Registered 43,391 Trablous En-Nouri Trablous et Tabbaneh Minie 54 6,404 17,610 Raouda-Aadoua Total No. of Individuals Registered 175,637 Trablous El-Qobbe 201 10,079 Merkebta Mina N 1 256 Mina N 3 Nabi Youcheaa 3,103 Deir Aammar 270 3,717 Borj El-YahoudHiyreaiqis Beddaoui 14 13 16,976 Mina N 2 Terbol-Miniye Mzraat Kefraya Mina Jardin 40 11 4,030 Qarhaiya Aasaymout Trablous Et-Tell Boussit 4 3,550 Aazqai Trablous jardins Hailan 204 Harf Es-Sayad Debaael 2,301 Mejdlaiya Zgharta 224 46 1 Qarne Aalma Kfar Chellane Btermaz Beit Haouik 3,464 730 132 42 Trablous El Mhatra 396 30 Miriata Aachach Mrah Es-Srayj Harf Es-Sayad Haouaret-Miniye Trablous El-Haddadine, El-Hadid, El-Mharta Tripoli Arde 2,094 17 152 Bakhaaoun 46 16 1,703 Trablous Ez-Zeitoun 628 18,633 Kfar Habou 2,613 Aardat Beit Zoud Trablous Es-Souayqa 576 tarane Qemmamine 85 4 Rachaaine 174 Sfire 457 Jayroun Ras Masqa 486 Kharroub-Miniye Kfar Bibnine 4,075 Tallet Zgharta Zgharta Haql el Aazime Mrah Es-Sfire 29 9 Danha 4 3,218 Kfardlaqous 52 13Qraine 135 2 Qattine-MiniyéAain Et-Tine-Miniyé 50 Hazmiyet-Miniye Mazraat Ajbeaa B83eit El-Faqs Aassoun Qarsaita Qalamoun Barsa Asnoun 184 Bkeftine Izal 2,417 192 3,755 796 Kfarhoura -

New Jurassic Amber Outcrops from Lebanon Youssef Nohra, Dany Azar, Raymond Gèze, Sibelle Maksoud, Antoine El-Samrani, Vincent Perrichot

New Jurassic amber outcrops from Lebanon Youssef Nohra, Dany Azar, Raymond Gèze, Sibelle Maksoud, Antoine El-Samrani, Vincent Perrichot To cite this version: Youssef Nohra, Dany Azar, Raymond Gèze, Sibelle Maksoud, Antoine El-Samrani, et al.. New Jurassic amber outcrops from Lebanon. Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews, Brill, 2013, 6, pp.27-51. 10.1163/18749836-06021056. insu-00844560 HAL Id: insu-00844560 https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-00844560 Submitted on 15 Jul 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. TAR Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 6 (2013) 27–51 brill.com/tar New Jurassic amber outcrops from Lebanon Youssef Nohra1,2,3, Dany Azar1,*, Raymond Gèze1, Sibelle Maksoud1, Antoine El-Samrani1,2 and Vincent Perrichot3 1Lebanese University, Faculty of Sciences II, Department of Natural Sciences, Fanar – Matn PO box 26110217, Lebanon e-mail: [email protected] 2Lebanese University, Doctoral School of Sciences and Technology – PRASE, Hadath, Lebanon 3Geosciences Rennes (UMR CNRS 6118), Université de Rennes 1, Campus de Beaulieu, building 15, 263, avenue du General-Leclerc, 35042 Rennes cedex, France *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] Received on October 1, 2012. -

Cultural Background

Cultural Background Funerary Patterns in Lebanon—From the Bronze Age to the Roman Period By Signe Krag 2 Hellenistic Cities in the Levant By Eva Mortensen 8 Hellenistic and Roman Sarcophagi in the Levant By Philip Ebeling 12 Maron and the Maronites By Niels Bargfeldt 19 1 Agora nr. 8 2011 Funerary Patterns in Lebanon—From the Bronze Age to the Roman Period By Signe Krag During the Bronze Age inhumation burials were the Photo: Signe Krag common practice in Lebanon. The evidence is very limited, but it suggests that several types of burials were used at the same time, namely jar burials (with inhumed infants and small children), rock-cut tombs, pit graves, cist graves and hypogea with chambers and possible sarcophagi. The burial gifts seem to have been placed in the graves according to the sex of the deceased, as men are often buried with weapons and women are buried with domes- tic objects and jewellery. Furthermore, luxury items are placed in some of the graves, a fact which sug- gests the existence of a society with marked social differences. At Sidon we find evidence for the prac- tice of animal sacrifice, and ovens that are placed at Fig. 1: The sarcophagus of Ahiram depicting mourning women. the graves suggest a belief in the afterlife of the deceased. On the sarcophagus of Ahiram from Byblos are depictions of mourning women which could tell us how the deceased was mourned. The evidence comes mainly from Beirut, Sidon and Byblos. During the Iron Age both inhumation and cremation burials were in use. -

Layout CAZA AAKAR.Indd

Qada’ Akkar North Lebanon Qada’ Al-Batroun Qada’ Bcharre Monuments Recreation Hotels Restaurants Handicrafts Bed & Breakfast Furnished Apartments Natural Attractions Beaches Qada’ Al-Koura Qada’ Minieh - Dinieh Qada’ Tripoli Qada’ Zgharta North Lebanon Table of Contents äÉjƒàëªdG Qada’ Akkar 1 QɵY AÉ°†b Map 2 á£jôîdG A’aidamoun 4-27 ¿ƒeó«Y Al-Bireh 5-27 √ô«ÑdG Al-Sahleh 6-27 á∏¡°ùdG A’andaqet 7-28 â≤æY A’arqa 8-28 ÉbôY Danbo 9-29 ƒÑfO Deir Jenine 10-29 ø«æL ôjO Fnaideq 11-29 ¥ó«æa Haizouq 12-30 ¥hõ«M Kfarnoun 13-30 ¿ƒfôØc Mounjez 14-31 õéæe Qounia 15-31 É«æb Akroum 15-32 ΩhôcCG Al-Daghli 16-32 »∏ZódG Sheikh Znad 17-33 OÉfR ï«°T Al-Qoubayat 18-33 äÉ«Ñ≤dG Qlaya’at 19-34 äÉ©«∏b Berqayel 20-34 πjÉbôH Halba 21-35 ÉÑ∏M Rahbeh 22-35 ¬ÑMQ Zouk Hadara 23-36 √QGóM ¥hR Sheikh Taba 24-36 ÉHÉW ï«°T Akkar Al-A’atiqa 25-37 á≤«à©dG QɵY Minyara 26-37 √QÉ«æe Qada’ Al-Batroun 69 ¿hôàÑdG AÉ°†b Map 40 á£jôîdG Kouba 42-66 ÉHƒc Bajdarfel 43-66 πaQóéH Wajh Al-Hajar 44-67 ôéëdG ¬Lh Hamat 45-67 äÉeÉM Bcha’aleh 56-68 ¬∏©°ûH Kour (or Kour Al-Jundi) 47-69 (…óæédG Qƒc hCG) Qƒc Sghar 48-69 Qɨ°U Mar Mama 49-70 ÉeÉe QÉe Racha 50-70 É°TGQ Kfifan 51-70 ¿ÉØ«Øc Jran 52-71 ¿GôL Ram 53-72 ΩGQ Smar Jbeil 54-72 π«ÑL Qɪ°S Rachana 55-73 ÉfÉ°TGQ Kfar Helda 56-74 Gó∏MôØc Kfour Al-Arabi 57-74 »Hô©dG QƒØc Hardine 58-75 øjOôM Ras Nhash 59-75 ¢TÉëf ¢SGQ Al-Batroun 60-76 ¿hôàÑdG Tannourine 62-78 øjQƒæJ Douma 64-77 ÉehO Assia 65-79 É«°UCG Qada’ Bcharre 81 …ô°ûH AÉ°†b Map 82 á£jôîdG Beqa’a Kafra 84-97 GôØc ´É≤H Hasroun 85-98 ¿hô°üM Bcharre 86-97 …ô°ûH Al-Diman 88-99 ¿ÉªjódG Hadath -

Occupancy Rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability

[Type here] Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Tuesday, February 09, 2021 Report #328 Time Published: 08:30 PM Occupancy rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability For daily information on all the details of the beds distribution availability for Covid-19 patients among all governorates and according to hospitals, kindly check the dashboard link: Computer:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-PCPhone:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-Mobile Ref: Ministry of public health Distribution by Villages Beirut 252 Baabda 494 Maten 189 Chouf 149 Keserwan 126 Aley 152 Ain Mraisseh 2 Chiyah 37 Borj Hammoud 17 Damour 3 Jounieh Sarba 9 Aamroussiyeh 17 Aub 1 Jnah 19 Nabaa 3 Saadiyat 2 Jounieh Kaslik 4 Hay Es Sellom 26 Manara 3 Ouzaai 24 Sinn Fil 4 Naameh 5 Zouk Mkayel 12 Khaldeh 13 Qreitem 2 Bir Hassan 12 Jisr Bacha 2 Haret En Naameh 2 Haret El Mir 3 El Oumara 28 Raoucheh 4 Madinh Riyadiyeh 1 Jdaidet Matn 10 Mechref 1 Jounieh Ghadir 4 Deir Qoubel 3 Hamra 13 Mahatet Sfair 2 Baouchriyeh 8 Chhim 26 Zouk Mosbeh 13 Aaramoun 19 Snoubra 1 Ghbayreh 20 Daoura 5 Mazboud 1 Adonis 4 Baaouerta 1 Ain Tineh 2 Ain Roummaneh 25 Raoda Baouchreh 8 Dalhoun 1 Haret Sakhr 6 Bchamoun 11 Msaitbeh 16 Furn Chebbak 9 Sad Baouchriyeh 3 Daraiya 10 Sahel Aalma 6 Maaroufiyeh 1 Ouata Msaitbeh 1 Haret Hreik 61 Sabtiyeh 5 Ketermaya 4 Kfar Yassine 2 Blaybel 2 Mar Elias 3 Laylakeh 35 Deir Mar Roukoz 1 Aanout 4 Tabarja 6 Aaley 8 Tallet Khayat 5 Borj Brajneh 93 Dekouaneh 12 Sibline 1 Adma Oua Dafneh 5 Kahhaleh 2 Dar Fatwa 3 Mreijeh 20 Antelias 9 Bourjein 1 Safra 2 -

Batroun Koura Minié-Danniyé Zgharta Bcharré Tripoli SYRIA REFUGEE

SYRIA REFUGEE RESPONSE LEBANON North Governorate, Tripoli, Batroun, Bcharreh, El Koura, El Minieh-Dennieh, Zgharta Districts (T+5) Informal Settlements (IS) Locations and Number of Persons per IS As of 11 April 2014 Zouq Bhannine 006 Zouq Bhannine 007 Zouq Bhannine 003 (59) (198) Zouq Bhannine 005 N Zouq Bhannine 009 " (326) P P (185) 0 ' 0 (334) 3 Zouq Bhannine 008 ° P 4 1:10,000 P (128) 3 P P P Rihaniyet-Miniye P Zouq Bhannine 001 0 100 200 400 Meters ZPouq BhanniPneP Merkebta 040 P Merkebta 009 (207) (1P 02) Zouq Bhannine 010 PP (51) P P (152) P P P P PP Merkebta 026 P MinMieerkebta 014 PP P P (68) P PP PP PPP (110) PPP P P P Merkebta 002 PPPP P P P Minie 015 PP Raouda-Aadoua P PPP P (135) Minie 001 PP P (60) P P Minie 002 P Merkebta 005 Merkebta (386) P (57) P (400) Borj El-Yahoudiyé 001 P (116) Merkebta 007 Markabta 033 Deir Aammar Nabi Youcheaa Merkebta 004 P P (170) (85) (90) Borj El-Yahoudiye Nabi Youcheaa 001 Hraiqis P P Minie 016 P Minie 005 Mina N 3 (70) P Merkebta 001 Minie 022 P Mina N 1 Trablous jardins Beddaoui (143) (174) Mina N 2 (237) Mzraat Kefraya (113) Terbol-Miniye Raouda-Aadoua 003 P Raouda-Aadoua 001 Mina Jardin (105) Minie Boussit (47) Minie 004 P P Qarhaiya Aasaym out Minie 006 P Trablous Et-Tell Aalma 002 (464) Aazqai 001 Aazqai Mejdlaya 001 (105) Debaael PP P (70) Trablous Es-Souayqa P Hailan (100) Harf Es-Sayad (120) P Btermaz Minie 009 P Minie 017 P Aalma Qarne Kfar Chellane Beit Haouik (70) Miriata 003 P (158) Mejdlaiya Zgharta P (70P) P Harf Es-Sayad Tripoli Haouaret-Miniye Mrah Es-Srayj Trablous Ez-Zeitoun -

Stakeholder Engagement Plan 9 October 2018 CEPF Grant 108784

Stakeholder Engagement Plan 9 October 2018 CEPF Grant 108784 Friends of Nature CONSERVING LEBANON ENDEMIC FLORA THROUGH COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT Also serving as Stakeholder Engagement Plan for CEPF Grant 108497 Université Saint Joseph CONSERVER ET VALORISER LE PATRIMOINE BOTANIQUE UNIQUE DU LIBAN Orontes Valley and Levantine Mountains Grant Summary 1. Grantee organization: The Friends of Nature 2. Grant title: CONSERVING LEBANON ENDEMIC FLORA THROUGH COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT, AND CONSERVER ET VALORISER LE PATRIMOINE BOTANIQUE UNIQUE DU LIBAN 3. Grant number : CEPF-108784 & 108497 4. Grant amount (US dollars): 154,860 + 135,035 = 289,895 US$ 5. Proposed dates of grant : October 2018 – October 2020 6. Countries or territories where project will be undertaken: Orontes Valley and Levantine Mountains 7. Date of preparation of this document : 9 October 2018 8. Introduction: The two projects address the conservation of 7 priority sites in 3 KBAs where critically endangered floral species and endemic plants of restricted distribution ranges occur. The type of activities vary from one site to the other, and call for different approaches. § Bcharri – Makmel region : the project will explore the feasibility of conservation and the study of conservation measures through a community participatory approach. An action plan and a management plan will be prepared within the framework of this project for the eventual creation of a micro-reserve or other innovative forms of conservation measures; however, no restrictions are foreseen within the project mandate. § Kneisseh summit : the project will explore the feasibility of conservation and the study of conservation measures through a community participatory approach. An action plan and a management plan will be prepared within the framework of this project for the eventual creation of a micro-reserve or other innovative forms of conservation measures; however, no restrictions are foreseen within the project mandate.