Management of Judo Federations: a Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tales of a Canadian Judoka Michelle Marrian Anna

Twentieth Century Travels: Tales of a Canadian Judoka Michelle Marrian Anna Rogers B.A., University of British Columbia, 2000 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology O Michelle Marrian Anna Rogers, 2005 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permissions of the author ABSTRACT Supervisor: Dr. Andrea Walsh In 1960, Doug Rogers, my father, travelled to Japan to study the martial art of judo. In Japan, Rogers was able to hone his abilities in judo, which enabled him to succeed in competition at both the national and international level. Using photographs belonging to Rogers that were taken during the time he went to Japan (1960-1965), I was able to enter into a series of conversations with him about his reasons for travelling to Japan and his experiences during his stay there. Rogers' early life provides an opportunity to not only explore the unique experiences of an important individual in Canadian and Japanese sports history, but a chance to investigate specific examples of how large-scale, 'global' processes (the circulation of media, culture 'flows', and historical processes and events) can influence at the level of the individual. I examine how Rogers' original decision to travel to 'traditional' and 'exotic' Japan, and his actual stay in Japan, were contingent upon a revised cultural heritage that Japan was trying to project after the Second World War, which displayed Japan as a peaceful, proper, ethnically homogenous, and aesthetically-oriented nation. -

Handbook.Pdf

MooseMoose JawJaw KoseikanKoseikan JudoJudo ClubClub 2021-2022 www.mjjudo.com ParentsParents andand JudokaJudoka HandbookHandbook September 2021 Aug 30– Sept 2, Registration and first nights of class 17-19, Judo Sask High Performance Camp, Moose Jaw October 2021 11, Thanksgiving, no classes November 2021 11, Remembrance Day, no classes 13-14, Quebec Open, Montreal 20, Judo Sask Annual General Meeting, Watrous December 2021 17, Last day of Judo for Holiday Break January 2022 3, First day of back to Judo 15-16 Elite Nationals 22-23, Manitoba Open February 2022 21-25, No classes for school break March 2022 4-8, Edmonton International Championships 11-13, Pacific International, Richmond, BC April 2022 15-22, Easter Break, no classes May 2022 5, Last day of classes 19-22, National Judo Championships The dates on this list are subject to change.For updates to this list, check the events calendar at www.mjjudo.com, or the bulletin board at the Dojo Moose Jaw Koseikan Judo Club 2021-2022 Class Fee Schedule All fees are due and payable on the first day of each semester. If necessary, club fees may be paid by post-dated cheques as stated. In the case of an NSF cheque, a $20.00 penalty will be imposed to offset bank charges. BEGINNER: Club Fees: $285 for the season Can be paid in instalments with 3 post dated cheques for $95 each YOUTH: Club Fees: $475 for the season Can be paid in instalments with 5 post dated cheques for $95 each ADULT: Club Fees: $475 for the season Can be paid in instalments with 5 post dated cheques for $95 each Family Rates are available - For families with three or more registered members participating at the club level, a discount of 20% will be applied to the total registration fee for the family (not including family members who only pay associate membership fee) Children 18 and older are considered independent and are not included in the family package. -

Judospacenewsletter 2014

Judospace Newsletter 2014 Supporting Player and Coach Education A SNAPSHOT OF OUR AC TIVITIES IN 2014 An Exciting Year At Judospace... December 2014 May nership to deliver EJU Level 3 Visit to Johannesburg South Award in Oslo. Africa to deliver Level 3 EJU Ad- Working to vanced Coach course with Dar- Hellenic Judo Federation partner- ren Warner. ship to deliver the EJU Level 3 improve the Award in Athens, Greece standards of January Partnership established between Dr Mike Callan & Nick Fletcher judo across Athlete Performance Panel Hellenic Judo Federation and the world launched. Judospace. attended the World Kata Cham- pionships and the IJF Kata Train- through im- Rebeka Tandaric & Samobor Judospace 5th Birthday! ing Camp, Malaga, Spain. proving the Judo Klub conduct physiology June knowledge, testing at Anglia Ruskin. Research away day organised by Professor Fumiaki Shishida, Anglia Ruskin Sport & Exercise skills and February Waseda University, visits Ju- Science Research Group. understand- Organised visit of the All Japan dospace offices and Bowen Ar- ing of the coaches, players University Judo Association to chive. Janine Johnson, Judospace Exec- the Budokwai & Oxford Univer- utive Assistant shortlisted in the and federations. Trevor Leggett centenary premi- sity. top 10 for the Newcomer PA of ere at BAFTA, London. the year award by Executive PA March magazine. July Visit from Dr Ryo Uchida of Organised the Commonwealth Nagoya University, Japan. Prof Katsumi Mori from Kanoya Judo Association congress and University visits Judospace to Inside this issue: Coach education seminar for elections in Glasgow. discuss child protection. Judo Federation Iceland. Andy Burns wins Commonwealth Partnership established with GREETINGS FROM 2 Dr Callan met Mr Nikos Iliadis in Games medal. -

2030 Commonwealth Games Hosting Proposal – Part 1

Appendix B to Report PED18108(b) Page 1 of 157 2030 Commonwealth Games Hosting Proposal – Part 1 – October 23, 2019 – Appendix B to Report PED18108(b) Page 2 of 157 !"#"$%&''&()*+,-.$/+'*0$1$%+(23-45*$6+5-$7$1$&89:;<=$!#>$!"7?$ $ -C;D<$:G$%:A9<A9F$ $ $ #$ %&'"()*)+,"-+'"./0"!121"3450*" 7H7H 5<9I=AJAK$9:$9E<$6DC8<$)E<=<$39$+DD$L<KCAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH M$ 7H!H ,<KC8N$:G$9E<$7?#"$L=J9JFE$*@OJ=<$/C@<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH P$ 7H#H +$%<A9<AC=N$%<D<;=C9J:A HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Q$ 7HMH &I=$RJFJ:A$G:=$!"#" HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH ?$ 7HPH -=CAFG:=@JAK$&I=$%J9N HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7"$ 7HPH7 (<B$0O:=9$SC8JDJ9J<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7"$ 7HPH! LIJDTJAK$.C@JD9:AUF$0O:=9$-:I=JF@$%COC8J9N HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 77$ 7HPH# 2J=<89$*8:A:@J8$3@OC89 HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7!$ 7HPHM -=CT<$CAT$3AV<F9@<A9$&OO:=9IAJ9J<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7#$ 7HPHP +GG:=TC;D<$.:IFJAK HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7M$ 7HPHQ .C@JD9:AUF$0IF9CJAC;D<$SI9I=<$W$/=<<AJAK$9E<$/C@<FHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 7M$ 7HPHX *AKCKJAK$R:DIA9<<=F -

Buyersguide Cv2011 12 Editorial Pages 07/07/2011 15:57 Page 1

buyersguide cv2011_12_Editorial Pages 07/07/2011 15:57 Page 1 BUYERS’ GUIDE 2011/12 SPORTS INSIGHT SPORTS BUYERS’ GUIDE20011/12Sportswww.sports-insight.co.uk WWW.SPORTS-INSIGHT.CO.UK PRICE £9.99 Insight MAKURASPORT.COM Reydon_Layout 1 19/07/2011 15:07 Page 1 1 - Contents_Intro page 22/07/2011 14:58 Page 3 Contents Every cloud… More takeovers will occur in the UK sports and leisurewear sector this year, if a recent industry report is to be believed. Financial analyst Plimsoll says one in five companies could change ownership as a result of too many firms chasing too little market. One of the most fragmented sectors in the UK, it appears that some businesses are facing an uncertain future. The winners will be cash rich rivals, waiting to swoop on companies put up for sale at rock bottom prices. CONTENTS A potential silver lining for the sports trade next year could be the London Olympics. One sports retailer in the capital said part of the legacy of London 2012 would be a new breed of competitors and a fresh wave of up and coming athletes for retailers to kit out and 18 Sports merchandisers 44 Sports agents support. I hope this is the case and your 25 Sports governing bodies 48 Buying groups/multiples business’ bottom line benefits as a result. 34 Trade associations 52 Suppliers A-Z listing Jeff James 36 Marketing specialists 92 Independent sports retailers 42 Association of 184 Suppliers by product Editor Professional Sales Agents category Although every care is taken to ensure that all Published by Design/Typesetting information is accurate and up to date, the publisher Maze Media (2000) Ltd, Ace Pre-Press Ltd, 19 Phoenix Court, cannot accept responsibility for mistakes or omissions. -

Visually Impaired Friendly Judo

Visually Impaired Friendly Judo A Guide for Supporting Visually Impaired Adults and Children in a Judo Environment A Visible Difference Through Sport Visually Impaired Friendly Judo Contents Section One: Understanding Visual Impairments Page 6 1.1. What is Visual Impairment? Page 6 1.2. Understanding Common Visual Impairment Conditions Page 7 Case study: Chris Skelley Page 8 Section Two: Making Judo Accessible for Visually Impaired People Page 9 2.1. Coaching Visually Impaired Judoka Page 9 2.2. Event Literature Page 13 2.3. Guiding Visually Impaired People Page 13 2.4. Health and Safety Page 14 Case study: Ben Quilter Page 15 Section Three: Competitive Judo for Visually Impaired Judoka Page 17 3.1. Classification Page 17 3.2. IBSA Amendments for Visually Impaired Judo Competition Page 18 3.3. Pathways for Blind and Partially Sighted Judoka Page 20 Case study: Jean-Paul Bell Page 21 Section Four: Further Information Page 22 4.1. Resources and Guidance Page 22 4.2. Useful Contacts Page 22 Summary and Best Practice Page 23 Page 1 Introduction Welcome to the Visually Impaired Friendly Judo “British Blind Sport is resource. This resource has been produced by committed to providing British Blind Sport in partnership with the British sport and recreational Judo Association. opportunities for all blind and partially At British Blind Sport, we believe every person sighted adults and with sight loss has the right to participate in the children across sport of their choice. However, we understand Great Britain from there are many barriers to overcome to ensure grassroots to elite every visually impaired (VI) person has the level. -

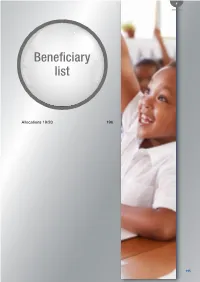

Beneficiary List

F Beneciary list Beneciary list Allocations 19/20 196 National Lotteries Commission Integrated Report 2019/2020 195 ALLOCATIONS 19/20 Date Sector Province Proj No. Name Amount 11-Apr-19 Arts GP 73807 CHILDREN’S RIGHTS VISION (SA) 701 899,00 15-Apr-19 Arts LP M12787 KHENSANI NYANGO FOUNDATION 2 500 000,00 15-Apr-19 Sports GP 32339 United Cricket Board 2 000 800,00 23-Apr-19 Arts EC M12795 OKUMYOLI DEVELOPMENT CENTER 283 000,00 23-Apr-19 Arts KZN M12816 CARL WILHELM POSSELT ORGANISATION 343 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12975 MANYAKATANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 200 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts WC M13008 ACTOR TOOLBOX 286 900,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12862 QUEEN OF RAIN ORPHANAGE HOME 321 005,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12941 GO BACK TO OUR ROOTS 351 025,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12835 LAEVELD NATIONALE KUNSTEFEES 1 903 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities FS M12924 HAND OF HANDS 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities KZN M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities EC M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13031 ABAFAZI BENGOMA 184 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts WC M12945 HOOD HOP AFRICA 330 360,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13046 BORN TWO PROSPER 340 884,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13021 SA INDUSTRIAL THEATRE OF DISABILITY 1 509 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts EC M12850 NATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 3 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12841 Flying Birds Handball Club 126 630,00 30-Apr-19 Sports KZN M12879 Ferry Stars Football Club 128 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12848 Blakes Rugby Football Club 147 961,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12930 Riverside Golf Club 200 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12809 Mpumalanga Rugby -

Competitive School Sport Summary Report

National Governing Bodies of Sport Survey Competitive School Sport Summary Report June 2014 Prepared by the TOP Foundation for Ofsted SportPark, Loughborough University, 3 Oakwood Drive, Loughborough, LE11 3QF NGB Competitive School Sport Investigation Summary Report Executive Summary In the spring of 2014 an investigation commissioned by Ofsted explored the school backgrounds, ethnicity and socioeconomic status of some of our best adult and age group international sport teams. The same investigation asked 29 National Governing Bodies of sport (NGBs) to report on their competitive school sport provision in 39 different sports; 26 (90%) NGBs agreed to take part and they reported on 35 sports. This NGBs report is part of a wider investigation being undertaken by Ofsted into competitive school sport for Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Education, Children’s Services and Skills (HMCI), Sir Michael Wilshaw, which includes a supporting report with input from headteachers. This investigation collated 6 different sets of data on the known school backgrounds of: i. Current international representatives from 14 sports (n=224) ii. London 2012 Olympic Team (n=279) iii. London 2012 Paralympic Team (n=106) iv. Players competing in national leagues in 5 sports (n=543) v. UK Sport’s Athlete Insights Survey: Olympic sports (n=606) vi. UK Sport’s Athlete Insights Survey: Paralympic sports (n=247). Analysis showed similar trends across the different data sets. The 2 Paralympic data sets provided a mean of 81% for athletes attending state schools only, 13% for independent schools only and 3% for both types of school. The 2 Olympic data sets provided a mean of 66% for athletes attending state schools only, 22% for independent schools only and 6% for both types of school. -

And Judo Dent on the Motorway

... I m ,• 0 > z i r -< ~ c: ", 0 0 • C> • ,. i " " "0 ~ m< 0 e ,. - Z -" 0 ; m" '. 0 ~ "s: e s: mz 0 m I 0 •n -< • '"... ~ I • m run, Mick (he looks so soft) swept hard, but Eddie was all over him. the running Debelius down with It is however to Maidstone's credit kosoto for yuko, and it was almost that he only losl by yuko. World Judo Championships - Vienna 1.7$ immediately time. A win to Scot land. Neenan" McArec This was youth v experience. A CANTERBURY TRAVEL in asSOCiatIOn with JUDO LTD., offer readers Inman v Rae fierce, ding-dong bailie. but ex of "Judo" and their friends-2 Inclusive Tours-using scheduled Airline These two "set-to" for real. Ihtl perience won. Veteran McAree did Services from London Heathrow Airporl to attend the World Championships less experienced Rae not in the least a repeat of his effort in last year's in Vienna on the 23rd. 24th and 25th October 1975. overawed by Inman. To prove it Inter-areas, by winning Ihis dttisive The tours are for 4 or 5 night with acommodation in a seltttion of hotels he dumped Roy for waza·ari, with match for Scotland by yuko. on a bed and Continental breakfast basis-with transfers from airport to Uchimala. giving a final result of ScOUllnd 3, hotel and vice versa. Inman came back fiercely. which England 2, TOUR "A' provoked Rae into a careless The team rcfust:d to leave the 4 nights nnd Oct. depart 11.05 hrs. return landing 26th Oct. -

Ioc Olympic Studies Centre Advanced Olympic Research Grant Programme 2014/2015

IOC OLYMPIC STUDIES CENTRE ADVANCED OLYMPIC RESEARCH GRANT PROGRAMME 2014/2015 FINAL REPORT OLYMPIC MOVEMENT STAKEHOLDER COLLABORATION FOR DELIVERING ON SPORT DEVELOPMENT IN EIGHT AFRICAN (SADC) COUNTRIES CORA BURNETT UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG OLYMPIC STUDIES CENTRE (UJOSC) & DEPARTMENT OF SPORT AND MOVEMENT STUDIES, JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA May 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. THE RESEARCH 5 2.1 Phases 5 2.2 Aims and objectives 6 3. METHODOLOGY 7 3.1 Research framework 7 3.2 Methods 7 3.3 Sample 7 3.4 Data analysis 9 4. CASE STUDIES 10 4.1 Botswana 10 4.2 Lesotho 15 4.3 Namibia 19 4.4 Seychelles 24 4.5 South Africa 27 4.6 Swaziland 34 4.7 Zambia 37 4.8 Zimbabwe 41 5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS 45 6. RECOMMENDATIONS 49 7. THE ACADEMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF THE RESEARCH 49 8. REFERENCES 50 9. Annexures 54 Annexure A: Map Annexure B: Pictures Annexure C: Methodology Annexure D: Olympic Education Workshop 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following agencies are recognised: • The IOC for funding and guidance relating to this research, as well as staff from the International Olympic Study Centre, especially Nuria Puig, for assistance during the research process. • All leadership at in-country NOCs and competent staff members for assisting with logistical arrangements and providing in-country support. The wide reach is contributed to them identifying research participants, providing a venue, local guide and venue when needed. • All research participants who committed their time and shared their expertise during often long and intricate discussions and interviews. -

Sport-And-Physical-A

Monday 21st September 2020 Dear Prime Minister, Today we are calling on you to commit to positioning sport and physical activity at the heart of our nation’s post-Covid renewal. This appeal comes from a broad range of organisations that include governing bodies and those who represent hundreds of thousands of sports clubs and facilities. Our sports engage millions of children, young people, and adults every year. Our sector drives economic prosperity and social change in the UK, contributing over £16bn to the UK economy and employing more than 600,000 people. A report published by Sport England and Sheffield Hallam University this month showed that every £1 spent on community sport and physical activity generates nearly £4 for the English economy, providing an annual contribution of more than £85bn, with a social value – including physical and mental health and wellbeing, individual and community development – of more than £72bn. Grassroots sport, fitness, and wider recreational activity is proven to improve physical, mental, and social wellbeing. This makes our sector an essential service as our nation recovers from the damage caused by Covid-19. Prime Minister – you’ve long been a champion of the benefits of a physically active lifestyle and we were heartened to hear that commitment renewed this summer with the launch of the Government’s obesity strategy. Our combined sector is delighted to be showcasing its reach into the heart of communities this week as part of the inaugural Great British Week of Sport. However, we are united in our concern that at a time when our role should be central to the nation’s recovery, the future of the sector is perilous. -

05-December-2012 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tiers 2 & 5 and Sub Tiers Only) DATE: 05-December-2012 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under Tiers 2 & 5 of the Points-Based System. It shows the organisation's name (in alphabetical order), the tier(s) they are licensed for, and whether they are A-rated or B-rated against each sub-tier. A sponsor may be licensed under more than one tier, and may have different ratings for each tier. No. of Sponsors on Register Licensed under Tiers 2 and 5: 25,750 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier (aq) Limited Leeds West Yorkshire Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General ?What If! Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) @ Bangkok Cafe Newcastle upon Tyne Tyne and Wear Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General @ Home Accommodation Services Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 5TW (A rating) Creative & Sporting 1 Life London Limited London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1 Tech LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 100% HALAL MEAT STORES LTD BIRMINGHAM West Midlands Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000heads Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000mercis LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) 101 Thai Kitchen London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 101010 DIGITAL LTD NEWARK Page 1 of 1632 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 108 Medical Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 111PIX.Com Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 119 West st Ltd Glasgow Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 13 Artists Brighton Tier 5TW (A rating) Creative & Sporting 13 strides Middlesbrough Cleveland Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 145 Food & Leisure Northampton Northampton Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 15 Healthcare Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 156 London Road Ltd t/as Cake R us Sheffield S.