Ioc Olympic Studies Centre Advanced Olympic Research Grant Programme 2014/2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 for WRITTEN REPLY

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY QUESTION No. 2026 FOR WRITTEN REPLY DATE OF PUBLICATION IN INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER: Mr G R Krumbock (DA) to ask the Minister of Sports, Arts and Culture: (1) When last was each national competition of each South African sports federation held; (2) What (a) total number of national federations has the SA Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (SASCOC) closed down since its establishment and (b) were the reasons in each case; (3) what (a) total number of applications for membership has SASCOC refused since its inception and (b) were the reasons in each case? NW2587E 1 REPLY (1) The following are the details on national competitions as received from the National Federations that responded; National Federations Championship(s) Dates South African Youth Championships October 2019 Wrestling Federation Senior, Junior and Cadet June 2019 Presidents and Masters March 2019 South African South African Equipped Powerlifting Championships 22 February 2020 Powerlifting Federation - Johannesburg Roller Sport South SA Artistic Roller Skating 17 - 19 May 2019 Africa SA Inline Speed skating South African Hockey Indoor Inter Provincial Tournament 11-14 March 2020 Association Cricket South Africa Proteas (Men) – Tour to India, match was abandoned 12 March 2020 without a ball bowled (Covid19 Impacted the rest of the tour). Proteas (Women)- ICC T20 Women’s World Cup 5 March 2020) (Semifinal Tennis South Africa Seniors National Competition 7-11 March 2020 South African Table Para Junior and Senior Championship 8-10 August 2019 Tennis Board -

Prevention Through Education Ensuring Effective Mechanisms of Delivery for Values-Based Messages Play True // an OFFICIAL PUBLICATION of the WORLD ANTI-DOPING AGENCY

ISSUE 1 - 2013 AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLD ANTI-DOPING AGENCY Prevention through Education Ensuring effective mechanisms of delivery for values-based messages play true // AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLD ANTI-DOPING AGENCY THE WORLD ANTI-DOPING AGENCY [email protected] wada-ama.org facebook.com/wada.ama twitter.com/wada_ama HEADQUARTERS 22 800 PLACE VICTORIA - SUITE 1700 P.O. BOX 120 MONTREAL, QC CANADA H4Z 1B7 TEL: +1 514 904 9232 FAX: +1 514 904 8650 AFRICAN REGIONAL OFFICE PROTEA ASSURANCE BUILDING 8TH FLOOR GREENMARKET SQUARE CAPE TOWN 8001 SOUTH AFRICA TEL: +27 21 483 9790 FAX: +27 21 483 9791 ASIA/OCEANIA REGIONAL OFFICE C/O JAPAN INSTITUTE OF SPORTS SCIENCES 3-15-1 NISHIGAOKA, KITA-KU, TOKYO 115-0056 JAPAN TEL: +81 3 5963 4321 FAX: +81 3 5963 4320 EUROPEAN REGIONAL OFFICE MAISON DU SPORT INTERNATIONAL AVENUE DE RHODANIE 54 1007 LAUSANNE, SWITZERLAND TEL: +41 21 343 43 40 FAX: +41 21 343 43 41 LATIN AMERICAN REGIONAL OFFICE WORLD TRADE CENTER MONTEVIDEO TOWER II, UNIT 712 - 18TH FLOOR CALLE LUIS A DE HERRERA 1248 MONTEVIDEO, URUGUAY TEL: + 598 2 623 5206 FAX: + 598 2 623 5207 Photo: Action Images/Reuters EDITOR TERENCE O’RORKE Deputy Editor Catherine Coley CONTRIBUTORS // Messages LÉA Cleret Rob Koehler Nathalie Lessard Julie Masse Prof. Mike MCNamee 02 Nobody is above the rules of sport Jennifer Sclater Stacy Spletzer-Jegen At the start of the final year of his terms as WADA President, John Fahey looks back DESIGN AND LAYOUT JULIA GARCIA DESIGN, over a busy and productive six months for MONTREAL the world’s anti-doping community. -

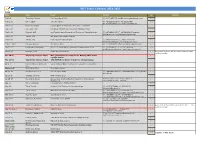

WTF Event Calendar 2014-2015 2014 Date Place Event Contact G Remark

WTF Event Calendar 2014-2015 2014 Date Place Event Contact G Remark Feb 8-9 Trelleborg, Sweden Trelleborg Open 2014 (T) +46709922594 [email protected] G-1 Feb 11-16 Luxor, Egypt 1st Luxor Open (T) +20222631737 (F) +20222617576 G-2 [email protected] / www.egypt-tkd.org Feb 13-16 Montreal, Canada Canada Open International Taekwondo Tournament G-1 Feb 18-24 Las Vegas, USA U.S Open International Taekwondo Championships G-2 Feb 20-22 Fujairah, UAE 2nd Fujairah Open International Taekwondo Championships (T) +97192234447 (F) +97192234474 fujairah- G-1 [email protected] / [email protected] Feb 21-23 Tehran, Iran 4th Asian Clubs Championships N/A Feb 24-26 Tehran, Iran 25th Fajr International Open (T) +982122242441 (F) +982122242444 G-1 [email protected] / www.fajr.iritf.org.ir Feb 27 - Mar 1 Manama, Bahrain 6th Bahrain Open (T) +73938888350 / [email protected] G-1 Mar 15-16 Eindhoven, Netherlands 41st Lotto Dutch Open Taekwondo Championships 2014 (T) +31235428867 (F) +31235428869 G-2 [email protected] / www.taekwondobond.nl Mar 15-17 Santiago, Chile South American Games G-1 Last event in March will be counted into the April ranking for GP1. Mar 20-21 Taipei City, Chinese Taipei WTF Qualification Tournament for Nanjing 2014 Youth N/A Olympic Games Mar 23-26 Taipei City, Chinese Taipei 10th WTF World Junior Taekwondo Championships N/A Apr 4-6 Santo Domingo, Dominican Santo Domingo Open International Taekwondo Tournament G-1 Rep. [Canceled] Kish Island, Iran West Asian Games G-1 Apr 11-13 Hamburg. Germany German Open -

Rapport Annuel UCI 2015

RAPPORT ANNUEL 2015 Table des matières Message du Président 4 RAPPORT DE GESTION ET DE PERFORMANCE 8 L’Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) 10 Un sport, huit disciplines 12 Rapport du Directeur Général 16 Relations internationales 20 Une année de sport et d’événements 24 Cyclisme sur route 26 Cyclisme sur piste 32 Mountain bike 36 BMX 40 Paracyclisme 44 Cyclo-cross 48 Trial 52 Cyclisme en salle 56 Le Centre Mondial du Cyclisme (CMC) UCI 60 Vélo pour tous 68 Événements de masse 70 Clean Sport 72 RAPPORT FINANCIER 76 Commentaire du CFO et Chiffres clés 78 Rapport du Comité d’Audit au Congrès de l’UCI 82 Rapport de l’Auditeur sur les Comptes Consolidés 84 États Financiers Consolidés 86 Rapport de l’Auditeur sur les États Financiers Statutaires 108 Comptes Statutaires 110 UCI WorldTour 114 ANNEXES Liste des Fédérations Nationales 116 Comité Directeur et organisation générale 118 Commissions 120 Résultats et classements 2015 126 3 Message du Président Ce Rapport Annuel couvre ma deuxième année complète au poste de Président de l’Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI). J’estime qu’il reflète les progrès significatifs que nous avons accomplis dans la modernisation de notre organisation afin de veiller à ce qu’elle soit une Fédération Internationale remarquable par ses résultats et son intégrité. J’ai été élu Président en 2013 avec pour mandat de restaurer la confiance dans notre sport et l’UCI ainsi que leur crédibilité. En 2015, nous nous sommes appuyés sur les avancées réalisées l’année précédente afin de poursuivre cet objectif précis. L’UCI contribue à montrer la voie dans l’établissement des meilleures pratiques en termes d’intégrité et de transparence sportives. -

Africa Aquatics News

Africa Aquatics News July 2020 Volume 4 No 1 Message from the President SPORT HAS A MAJOR ROLE IN COMBATTING AND CONTAINING COVID-19 redesigned the 2020 International Despite the suspension of swimming calendar. competitions, the first quar- The Durban African Championships, ter of 2020 was eventful with the Tokyo Olympics and the Abu the hosting of the zone 2 Dhabi World Short Course Champi- and 4 championships respec- onships have all been postponed. tively in Accra (record par- Consequence: the swimmers have no ticipation of 17 nations) and particular objective in 2020 as far as Gaborone (12 countries) in resumption of official competitions addition to the three legs of before the months of November or the GP competitions in South December 2020 at the earliest. This Africa and the participation has never happened before in the his- of African swimmers in inter- tory of sport and as much as we national meetings or national know in that of aquatic sports. The championships in Europe, health and sports authorities have Asia or in the USA. acted correctly by suspending all This new edition of the CA- Dr Sam Ramsamy CANA President competitions in order to preserve the NA newsletter aims mainly at health of the athletes and that of the bringing you back the memo- public. We all hope that the conse- rable and unforgettable mo- The world has been now turned quences of the coronavirus on the ments experienced in 2019: upside down as a result of the pre- organization of sport and the eco- FINA World Championships sent endemic. -

2013SPORT and RECREATION New3.Indd

SOUTH AFRICA YEARBOOK 2013/14 South African sportsmen and women excelled on the world stage in 2013/14. The country’s Sport and national rugby and football teams both boosted their world rankings over the course of the year, while the Proteas remained the undisputed number one test cricket team. Perhaps the biggest upset in football in 2013 Recreation occurred at the FNB Stadium in Johannesburg on 19 November when Bafana Bafana, ranked 61st in the world, defeated world and European champions Spain by one goal to nil. It was a welcome boost for a team which had missed out on qualifying for the 2014 FIFA World Cup hosted by Brazil. Sport and Recreation South Africa (SRSA) The SRSA is the national department responsible for sport in the country. Aligned with its vision of an active and winning nation, it primarily focuses on providing opportunities for all South Africans to participate in sport; manages the regulatory framework; and provides funding for different sporting codes. The right to play and to participate in sport has been embodied in United Nations (UN) instruments such as the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women. It is recognised as a right, which all governments should make available to their people. In line with the constitutional imperatives, the SRSA has been assigned the powers and functions to develop and implement national policies and programmes regarding sport and recreation in the country. The SRSA aims to maximise access, development and excellence at all levels of participation in sport and recreation to improve social cohesion, nation-building and the quality of life of all South Africans. -

Judospacenewsletter 2014

Judospace Newsletter 2014 Supporting Player and Coach Education A SNAPSHOT OF OUR AC TIVITIES IN 2014 An Exciting Year At Judospace... December 2014 May nership to deliver EJU Level 3 Visit to Johannesburg South Award in Oslo. Africa to deliver Level 3 EJU Ad- Working to vanced Coach course with Dar- Hellenic Judo Federation partner- ren Warner. ship to deliver the EJU Level 3 improve the Award in Athens, Greece standards of January Partnership established between Dr Mike Callan & Nick Fletcher judo across Athlete Performance Panel Hellenic Judo Federation and the world launched. Judospace. attended the World Kata Cham- pionships and the IJF Kata Train- through im- Rebeka Tandaric & Samobor Judospace 5th Birthday! ing Camp, Malaga, Spain. proving the Judo Klub conduct physiology June knowledge, testing at Anglia Ruskin. Research away day organised by Professor Fumiaki Shishida, Anglia Ruskin Sport & Exercise skills and February Waseda University, visits Ju- Science Research Group. understand- Organised visit of the All Japan dospace offices and Bowen Ar- ing of the coaches, players University Judo Association to chive. Janine Johnson, Judospace Exec- the Budokwai & Oxford Univer- utive Assistant shortlisted in the and federations. Trevor Leggett centenary premi- sity. top 10 for the Newcomer PA of ere at BAFTA, London. the year award by Executive PA March magazine. July Visit from Dr Ryo Uchida of Organised the Commonwealth Nagoya University, Japan. Prof Katsumi Mori from Kanoya Judo Association congress and University visits Judospace to Inside this issue: Coach education seminar for elections in Glasgow. discuss child protection. Judo Federation Iceland. Andy Burns wins Commonwealth Partnership established with GREETINGS FROM 2 Dr Callan met Mr Nikos Iliadis in Games medal. -

2013 Annual Report a Direct Line ! OLYMPIC SOLIDARITY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 1 2 3 4 5 6

2013 ANNUAL REPORT A DIRECT LINE ! OLYMPIC SOLIDARITY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 1 2 3 4 5 6 200 WORLD CONTINENTAL 1 FOREWORDS 3 PROGRAMMES 4 PROGRAMMES • President of the International Olympic Committee 4 INTRODUCTION 13 INTRODUCTION 41 • Chair of the Olympic Solidarity Commission 5 ATHLETES REPORTS OF THE CONTINENTAL ASSOCIATIONS • Introduction 15 • Association of National Olympic Committees • Olympic Scholarships for Athletes “ Sochi 2014 ” 16 of Africa ( ANOCA ) 42 • Team Support Grant 17 • Pan-American Sports Organisation ( PASO ) 45 GENERAL • Continental Athlete Support Grant 18 • Olympic Council of Asia ( OCA ) 48 2 INTRODUCTION • Youth Olympic Games – Athlete Support 19 • The European Olympic Committees ( EOC ) 52 • Oceania National Olympic Committees ( ONOC ) 55 • Analysis of the year 2013 7 COACHES • Olympic Solidarity Commission 8 • Introduction 21 • Olympic Solidarity continental offices organisation 9 • Technical Courses for Coaches 22 • Organisation of the Olympic Solidarity international • Olympic Scholarships for Coaches 24 office in Lausanne 10 • Development of the National Sports Structure 26 OLYMPIC GAMES • 2013 Budget 11 5 SUBSIDIES NOC MANAGEMENT COUL. 4 • Introduction 28 INTRODUCTION 60 OK MK • NOC Administration Development 29 • XXII Olympic Winter Games in Sochi 60 • National Training Courses for Sports Administrators 30 C 38 • InternationalC 90 Executive TrainingC 82 Courses C 80 C 50 C 0 M 4 in SportsM Management 55 M 10 M 031 M 0 M 40 • NOC Exchanges 32 J 0 J 0 J 0 J 35 JC O90MPLEMENTAJ RY75 N 19 PROMOTIONN 10 OF OLYMPIC VALUESN 0 N 10 6 NP R0OGRAMMESN 5 • Introduction 34 • Sports Medicine 35 INTRODUCTION 62 • Environmental Sustainability in Sport 36 • 2013 Activities 62 • Women and Sport 37 • Sport for All 38 • Olympic Education, Culture and Legacy ( incl. -

Men's Athlete Profiles 1 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON

Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games - Men's Athlete Profiles 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON (CMR) Date Of Birth : 09/05/1989 Place Of Birth : Yaoundé Height : 160cm Residence : Region du Centre 2018 – Indian Open Boxing Tournament (New Delhi, IND) 5th place – 49KG Lost to Amit Panghal (IND) 5:0 in the quarter-final; Won against Muhammad Fuad Bin Mohamed Redzuan (MAS) 5:0 in the first preliminary round 2017 – AFBC African Confederation Boxing Championships (Brazzaville, CGO) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Matias Hamunyela (NAM) 5:0 in the final; Won against Mohamed Yassine Touareg (ALG) 5:0 in the semi- final; Won against Said Bounkoult (MAR) 3:1 in the quarter-final 2016 – Rio 2016 Olympic Games (Rio de Janeiro, BRA) participant – 49KG Lost to Galal Yafai (ENG) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2016 – Nikolay Manger Memorial Tournament (Kherson, UKR) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Ievgen Ovsiannikov (UKR) 2:1 in the final 2016 – AIBA African Olympic Qualification Event (Yaoundé, CMR) 1st place – 49KG Won against Matias Hamunyela (NAM) WO in the final; Won against Peter Mungai Warui (KEN) 2:1 in the semi-final; Won against Zoheir Toudjine (ALG) 3:0 in the quarter-final; Won against David De Pina (CPV) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2015 – African Zone 3 Championships (Libreville, GAB) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the final 2014 – Dixiades Games (Yaounde, CMR) 3rd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the semi- final 2014 – Cameroon Regional Tournament 1st place – 49KG Won against Tchouta Bianda (CMR) -

A N N U a L R E P O R T 2 0

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD Registered address: Block A, Equity Park 257 Brooklyn Road Brooklyn Pretoria 0181 Postal address: P O Box 1556 Brooklyn Square Pretoria 0075 Telephone: +27-12-362 0306 Fax: +27-12-362 2590 Auditors: Auditor-General Bankers: ABSA Nedbank First National Bank Rand Merchant Bank Standard Corporate Merchant Bank NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 Mr. A Erwin Minister of Trade and Industry Report of the National Lotteries Board for the period 1 April 2001 to 31 March 2002. It is my singular honour to submit the Annual Report of the National Lotteries Board and the National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund. J A Foster Chairman 2 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 CONTENTS PAGE NO. Chairperson’s Report 4 National Lotteries Board: 13 Report of the Auditor-General 14 Balance Sheet 15 Income Statement 16 Statement of Changes in Equity 17 Cash Flow Statement 18 Notes to the Financial Statements 21 National Lottery Distribution Trust Fund: 27 Report of the Auditor-General 28 Balance Sheet 29 Income Statement 30 Statement of Changes in Equity 31 Cash Flow Statement 32 Notes to the Financial Statements 33 Beneficiaries of Good Cause monies 36 NATIONAL LOTTERIES BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2002 3 CHAIRPERSON’S REPORT The support of South Africans for the National Lottery in the past two years has been phenomenal. Because of this support, the funds raised by the National Lottery for good causes are making a difference to the lives of the people of South Africa through the promotion of charitable work, the arts, culture, national heritage, sport and recreation. -

An Anthropological Study Into the Lives of Elite Athletes After Competitive Sport

After the triumph: an anthropological study into the lives of elite athletes after competitive sport Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements in respect of the Doctoral Degree in Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of the Free State Supervisor: Professor Robert Gordon December 2015 DECLARATION I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, declare that the thesis that I herewith submit for the Doctoral Degree of Philosophy at the University of the Free State is my independent work, and that I have not previously submitted it for a qualification at another institution of higher education. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that I am aware that the copyright is vested in the University of the Free State. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that all royalties as regards intellectual property that was developed during the course of and/or in connection with the study at the University of the Free State, will accrue to the University. In the event of a written agreement between the University and the student, the written agreement must be submitted in lieu of the declaration by the student. I, Susanna Maria (Marizanne) Grundlingh, hereby declare that I am aware that the research may only be published with the dean’s approval. Signed: Date: December 2015 ii ABSTRACT The decision to retire from competitive sport is an inevitable aspect of any professional sportsperson’s career. This thesis explores the afterlife of former professional rugby players and athletes (road running and track) and is situated within the emerging sub-discipline of the anthropology of sport. -

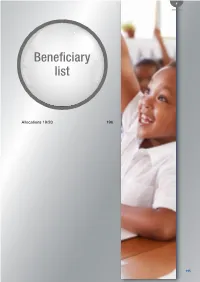

Beneficiary List

F Beneciary list Beneciary list Allocations 19/20 196 National Lotteries Commission Integrated Report 2019/2020 195 ALLOCATIONS 19/20 Date Sector Province Proj No. Name Amount 11-Apr-19 Arts GP 73807 CHILDREN’S RIGHTS VISION (SA) 701 899,00 15-Apr-19 Arts LP M12787 KHENSANI NYANGO FOUNDATION 2 500 000,00 15-Apr-19 Sports GP 32339 United Cricket Board 2 000 800,00 23-Apr-19 Arts EC M12795 OKUMYOLI DEVELOPMENT CENTER 283 000,00 23-Apr-19 Arts KZN M12816 CARL WILHELM POSSELT ORGANISATION 343 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12975 MANYAKATANA PRIMARY SCHOOL 200 000,00 24-Apr-19 Arts WC M13008 ACTOR TOOLBOX 286 900,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12862 QUEEN OF RAIN ORPHANAGE HOME 321 005,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12941 GO BACK TO OUR ROOTS 351 025,00 24-Apr-19 Arts MP M12835 LAEVELD NATIONALE KUNSTEFEES 1 903 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities FS M12924 HAND OF HANDS 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities KZN M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 29-Apr-19 Charities EC M13275 SIPHILISIWE 5 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13031 ABAFAZI BENGOMA 184 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts WC M12945 HOOD HOP AFRICA 330 360,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13046 BORN TWO PROSPER 340 884,00 30-Apr-19 Arts FS M13021 SA INDUSTRIAL THEATRE OF DISABILITY 1 509 500,00 30-Apr-19 Arts EC M12850 NATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 3 000 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12841 Flying Birds Handball Club 126 630,00 30-Apr-19 Sports KZN M12879 Ferry Stars Football Club 128 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12848 Blakes Rugby Football Club 147 961,00 30-Apr-19 Sports WC M12930 Riverside Golf Club 200 000,00 30-Apr-19 Sports MP M12809 Mpumalanga Rugby