JOCIH 3&4.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Money and Finance in the Wealth of Nations: Interpretations and Influences

Journal of US-China Public Administration, May 2015, Vol. 12, No. 5, 415-429 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2015.05.007 D DAVID PUBLISHING Money and Finance in the Wealth of Nations: Interpretations and Influences Mariano Castro-Valdivia University of Jaén, Jaén, Spain The paper analyzes the classical approach of the money and finance in the cited work of Adam Smith. Specifically, it studies the spread of these ideas in Spain in the late 18th and early 19th century. To do this, the above on this matter is investigated in the two editions that Alonso José Ortiz made of that work. In addition, their influence is discussed in the first Spanish edition of the Treaty of Political Economy by Jean Baptiste Say, translated by José Maria Queipo de Llano y Ruiz de Sarabia, 7th Count of Toreno. It should be remembered that it was a reference work for academic training in the chairs of political economy. In 1807, Plan Caballero, created in the Faculties of Law. Finally, it explains the influence that had the Smithian approach on this issue in the work of Ramón Lazaro de Dou y de Bassóls and Edualdo Jaumeandreui Triter. Keywords: money, teaching economics, classical school This paper is a study on the evolution of the concept of money in the principal text books used for teaching economics from the mid-eighteenth century to the early nineteenth century. Handbook of Genovesi, Condorcert, Smith, Herrenschwand, Canard, Say, Dou, and Jaumeandreu are studied in the following sections. The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith, is a land mark in modern economics. -

The University and the Region: an Historical Overview and Some Reflections on the Case of Catalonia

CONEIXEMENT I SOCIETAT 04 ARTICLES THE UNIVERSITY AND THE REGION: AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE CASE OF CATALONIA Ricard Pié* The increase in the number of publicly funded universities in Catalonia, the emergence of four private universi- ties, the major urban impact on the cities of Girona, Lleida, Reus, Tarragona and Vic as a result of the implantation of their respective universities, together with demographic factors such as the decline in the higher education population, as well as the need to rationalise the present map of universities in Catalonia, call for a considered appraisal of the relationship between the university and the region, as well as the relevance of that relationship to regional and academic restructuring policies affecting Catalan universities in the future. Contents 1. The university and its surrounding region 2. The founding of the medieval university, an urban phenomenon 3. The crisis of the traditional university model and the re-founding of the university as a temple of knowledge 4. The American experience: from rural college to mass university 5. The university as a motor of regional development 6. Spanish universities and their struggle for renewal 7. The difficult years, from the Spanish Civil War to the coming of democracy 8. The explosion of the university map in Spain under the new autonomous regions 9. The genesis of today’s university map in Catalonia 10. Some questions concerning the Catalan university map in relation to the differential value of region * Ricard PIÉ is an architect and senior lecturer at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia 16 THE UNIVERSITY AND THE REGION: AN HISTÒRICAL OVERVIEW AND SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE CASE OF CATALONIA 1. -

Fiestas and Fervor: Religious Life and Catholic Enlightenment in the Diocese of Barcelona, 1766-1775

FIESTAS AND FERVOR: RELIGIOUS LIFE AND CATHOLIC ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE DIOCESE OF BARCELONA, 1766-1775 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrea J. Smidt, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Dale K. Van Kley, Adviser Professor N. Geoffrey Parker Professor Kenneth J. Andrien ____________________ Adviser History Graduate Program ABSTRACT The Enlightenment, or the "Age of Reason," had a profound impact on eighteenth-century Europe, especially on its religion, producing both outright atheism and powerful movements of religious reform within the Church. The former—culminating in the French Revolution—has attracted many scholars; the latter has been relatively neglected. By looking at "enlightened" attempts to reform popular religious practices in Spain, my project examines the religious fervor of people whose story usually escapes historical attention. "Fiestas and Fervor" reveals the capacity of the Enlightenment to reform the Catholicism of ordinary Spaniards, examining how enlightened or Reform Catholicism affected popular piety in the diocese of Barcelona. This study focuses on the efforts of an exceptional figure of Reform Catholicism and Enlightenment Spain—Josep Climent i Avinent, Bishop of Barcelona from 1766- 1775. The program of “Enlightenment” as sponsored by the Spanish monarchy was one that did not question the Catholic faith and that championed economic progress and the advancement of the sciences, primarily benefiting the elite of Spanish society. In this context, Climent is noteworthy not only because his idea of “Catholic Enlightenment” opposed that sponsored by the Spanish monarchy but also because his was one that implicitly condemned the present hierarchy of the Catholic Church and explicitly ii advocated popular enlightenment and the creation of a more independent “public sphere” in Spain by means of increased literacy and education of the masses. -

Article JOURNAL of CATALAN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY, Issues 7&8, 2014 | Print ISSN 2014-1572 / Online ISSN 2014-1564 DOI: 10.2436/20.3001.02.88 | P

article JOURNAL OF CATALAN INTELLECTUAL HISTORY, Issues 7&8, 2014 | Print ISSN 2014-1572 / Online ISSN 2014-1564 DOI: 10.2436/20.3001.02.88 | P. 51-63 Reception date: 1/6/2013 / Admission date: 12/12/2013 http://revistes.iec.cat/index.php/JOCIH Tradition and renovation: the formation of Balmes and Martí d’Eixalà in their historic context Rafael Ramis Barceló Universitat de les Illes Balears [email protected] Josep M. Vilasojana Universitat Pompeu Fabra [email protected] abstract Jaume Balmes and Ramon Martí are certainly the most profound of the Catalan thinkers in the first half of the 19th century. This work shows some of the keys to contextualize their contributions, using the influences they received as a starting point. The basic objective of the comparison is to show that, although they come from similar sources, their positions in regard to combining tradition and modernity are different. The analysis ends with a paradox: Balmes, a more noted philosopher, did not enjoy the same level of direct influence as Martí d’Eixalà. keywords Ramon Martí d’Eixalà, Jaume Balmes, XIXth education. In this article we present the figures of Jaume Balmes and Ramon Martí d’Eixalà in their historic and cultural context, to try to highlight their simi- larities and differences in the framework of Catalan thinking in the first half of the XIXth. century. The two most relevant intellectuals of the epoch had very different impacts on the development of Catalan philosophy. Martí d’Eixalà was a sort of Albertus Magnus, a teacher of important thinkers and author of a work which tried to give a new orientation to the ideas of the epoch, with the novelty of the time, which in the XIIIth. -

Original E Castelltort Paupers' Hospital in Cervera

Received: 11 December 2012 / Accepted: 11 February 2013 © 2013 Sociedad Española de Neurología Original Neurosciences and History 2013; 1(2):88-93 e Castelltort paupers' hospital in Cervera: neurological and general care in the late 18th century J. A. Matías-Guiu, J. Matías-Guiu Department of Neurology, Instituto de Neurociencias, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Very little information is to be found about the care provided by paupers' hospitals in the 17th and 18th centuries. is article presents a review of the evolution and activity of the Castelltort paupers' hospital in Cervera, an inland town in Catalonia. We also analyse the hospital's admission and discharge records during that period. Although the hospital was funded primarily by donations, it also received support from the local government. Most of its patients suffered from infections or nutritional deficiencies. ere were very few neurological diagnoses; of the few we found, most are descriptive and correspond to pain and headache. Mortality rates were very high among the few patients hospitalised due to stroke. KEYWORDS 18th century; local hospital; paupers' hospital, Cervera, stroke, neurological disease. Introduction collection, the University records, and the Duran i Sampere legacy collection. We also consulted the follo - Very little is known about 17 th and 18 th century hospital wing historical archives corresponding to larger geogra - care, 1 and what we do know only applies to large or phical areas: Arxiu Històric Comarcal de Tàrrega, Arxiu medium-sized cities. 2,3,4 e literature contains no Històric Comarcal d’Igualada, Archivo de la Corona de descriptions of how medical care was provided in small Aragón, Archivo Histórico Nacional de Madrid, Arxiu towns or the level of neurological care that would have Parroquial de Cervera, Arxiu Històric de Protocols de been offered in this setting. -

Nuria Perez Paper Springer Re

Publicat a: Núria Pérez, Medicine Studies (2010) 2:37–48DOI 10.1007/s12376-010-0039-z Medicine and science in a new medical–surgical context: the Royal College of Surgery of Barcelona (1760–1843) ABSTRACT Taking the Royal College of Barcelona (1760 -1843) as a case study this paper shows the development of modern surgery in Spain initiated by Bourbon Monarchy founding new kinds of institutions through their academic activities of spreading scientific knowledge. Antoni Gimbernat was the most famous internationally recognised Spanish surgeon. He was trained as a surgeon at the Royal College of Surgery in Cadiz and was later appointed as professor of the Anatomy in the College of Barcelona. He then became Royal Surgeon of King Carlos IV and with that esteemed position in Madrid he worked resiliently to improve the quality of the Royal colleges in Spain. Learning human body structure by performing hands-on dissections in the anatomical theatre has become a fundamental element of modern medical education. Gimbernat favoured the study of natural sciences, the new chemistry of Lavoisier and experimental physics in the academic programs of surgery. According to the study of a very relevant set of documents preserved in the library, the so-called “juntas literarias”, among the main subjects debated in the clinical sessions was the concept of human beings and diseases in relation to the development of the new experimental sciences. These documents showed that chemistry and experimental physics were considered crucial tools to understand the unexplained processes that occurred in the diseased and healthy human body and in a medico-surgical context. -

Study in Catalonia

Study in Catalonia The University and Research System The University and Research CatalONIA Situated in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, Catalonia covers an area of approximately 32,000 km2 and has a population of over seven million inhabitants. Politically, Catalonia has the status of an autonomous community within Spain, with its capital being Barcelona, and has its own governing institution, the Generalitat de Catalunya (Government of Catalonia). It also has its own language, Catalan, which has official status along with Spanish. As they are both official languages, they may be used for all public and private activities. In general, the people of Catalonia are bilingual. In the shade of the Pyrenees and bathed by the Mediterranean Sea, Catalonia has been marked by the passing of numerous cultures, with a historical heritage recognised by the UNESCO (such as Parc Güell, Palau de la Música Catalana, the Sagrada Família, the monastery of Poblet, the Romanesque churches of La Vall de Boí and the archaeological sites of Tarraco, present-day Tarragona) and a geography in which one can travel from the sea to high peaks in little less than an hour. The life and customs of the Catalans are influenced by the region’s varied landscape, culture and art, all bathed in Mediterranean sunlight. Catalonia has a public body, the Agency for Quality Assurance abbreviation) in 2008, a roadmap for research and innovation for THE UNIVERSITY in the Catalan University System (AQU Catalonia), whose aim is the next 15 years. Through this agreement, the Catalan Govern- to guarantee the quality of higher education by meeting Euro- ment aims to make Catalonia an international leader in research AND RESEARCH pean quality standards, which is internationally recognised by the and development and a country at the cutting edge of science European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education and technology, by changing the current socioeconomic model TRADITION (ENQA). -

Printing Version Orobitg.Pdf

Welcome This web – site explains the history of an anonymous Catalan family that holds a peculiar surname: OROBITG. Being specially interested in a legend transmitted through generations according to which this surname was brought to Catalonia by a Russian soldier, we started investigating so as to confirm if it was true or not. Below you will find the results of a research carried out since 1977. The information sources used are the following: National Historical Archive of Madrid (ANHM - sources of the Monastery of the Virgin Mary of Poblet, Catalonia), University of Barcelona (‘Fogatges’ – ancient census), local archives (sources of ancient public notaries), ancient original documents kept by our family (wills, marriage contracts, …) and bibliography. We invite you to travel back to the XIII century, thus discovering how our ancestors lived. Though historical books do not relay on their daily fights, we should thank our existence to their day-to-day ‘small’ achievements. The outcome of the legend and the origin of the OROBITG surname will provide us with the opportunity to revive a common unknown past for most of you. READY, STEADY, GO! THE OROBITG FROM CATALONIA • Research from XIII to XV centuries ............................................................................................... 2 • Research XVI and XVII centuries .................................................................................................. 4 • Research from XVIII to XXI centuries .......................................................................................... -

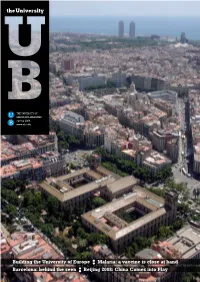

The University

the University THE UNIVERSITY OF BARCELONA MAGAZINE spring 2008 www.ub.edu Building the University of Europe Malaria: a vaccine is close at hand Barcelona: behind the seen Beijing 2008: China Comes into Play EDITORIAL 3 Editorial Barcelona, Capital of the European University Community The magazine you are holding in expand that aim to reach everyone in the European university commu- your hands, the English version of nity, a community which we are trying to build together. The UB is home La Universitat, has been timed to to a third of the students in the entire Catalan university system and it coincide with the spring confe- stands at the forefront of the university rankings. We want to share with rence of the European University you the UB’s innovation in teaching and research and our commitment Association (EUA) taking place on to the UB’s third mission, the transfer of knowledge, together with our 26-29 March in the University of high sense of social and institutional responsibility. To achieve these Barcelona’s Paranymph Hall. The aims, we are working at the local level in close partnership with the city conference marks the first gathe- of Barcelona and, more generally, our efforts seek to uphold the univer- ring of the EUA in Spain since the sity’s character as a strong force for social and democratic advance- association was founded in ment. In addition, the UB has a stated commitment to the economic Salamanca in 2001 and its focus transformation of Catalonia through knowledge transfer, technological this year will be on the gover- progress and active participation in the regional system of innovation that nance of European universities is embodied, in part, by the Barcelona Science Park. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Álvarez Junco, Mater Dolorosa, p. 25. 2. For the polemics between 1996 and 2004 see Tusell, Aznarato. For an overview of the national question in post-1970s Spain see Balfour and Quiroga, Reinvention of Spain. 3. Connor, ‘Terminological Chaos’, pp. 89–117. 4. See the comments in Halliday, ‘Formation of Yemini Nationalism’, pp. 26–42. 5. Anderson, Imagined Communities,p.6. 6. For a general study which incorporates an analysis of the Hispanic Habsburg Empire see Marx, FaithintheNation. 7. Smith, National Identity, pp. 76–8. 8. The key work for Catalonia is Torres Sans, Naciones sin nacionalismo. 9. Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism, pp. 14–21. 10. As analysed in some depth in Breuilly, Nationalism and the State, pp. 54–71. 11. Stressed in, for example, Breuilly, Nationalism and the State, p. 3; Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism, pp. 9–10. 12. The classic study is Kohn, Idea of Nationalism. 13. Because of its empirical weight, I would stress the importance of Baycroft and Hewitson (eds), What is a Nation? 14. Breuilly, Nationalism and the State, p. 3. Few academics would, however, accept Breuilly’s argument that the term nationalism should be restricted to such opposition groups. 15. Applegate, ‘A Europe of Regions’, pp. 1157–82. 16. Smith, National Identity, p. 146. 17. For a stimulating analysis see Umbach, ‘Nation and Region’, pp. 63–80. 18. Walker Connor, ‘Nation-Building or Nation Destroying?’, p. 43. 19. Breuilly, Nationalism and the State;Hroch,Social Preconditions. 20. Núñez Seixas, ‘Region’, pp. 483–518. 21. Smith, National Identity, pp. 20–1 and 66–7. -

The Catalan Legal Tradition (The Value of Interpretation and the Weight of History)

SPANISH JOURNAL OF LEGISLATIVE STUDIES ISSN 2695-5792 2019. Artículo 2 THE CATALAN LEGAL TRADITION (THE VALUE OF INTERPRETATION AND THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY) Dr. José María Pérez Collados Professor of History of Law at the University of Girona Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1.9.2019 Accepted: 1.10.2019 How to cite this paper Pérez Collados, Jose María (2019): The catalan tradition (the value of interpretation and the wei- ght of history). Spanish Journal of Legislative Studies. (1), p1-40. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21134/ sjls.v0i1.1707 THE CATALAN LEGAL TRADITION (THE VALUE OF INTERPRETATION AND THE WEIGHT OF HISTORY) Dr. José María Pérez Collados INTRODUCTION: THE LEGAL RE- mitation to a possible indiscriminate allegation of LEVANCE OF AN INDETERMINATE the Catalan legal tradition.’ LEGAL CONCEPT: THE CATALAN In other words, as article 111-1 affirms, the LEGAL TRADITION general principles of law are considered to be a legislative source with a dual-purpose integrative On 30th December 2002 the Catalan Parlia- function: on the one hand, they avoid heteroin- ment promulgated the first law of the Civil Code tegration, and on the other hand, they impede of Catalonia1. Its main objective, as stated in the ‘a possible indiscriminate allegation of the Ca- preamble, is to ‘establish the structure, the basic talan legal tradition’. The Catalan legal tradition, content and the procedural processes of the Civil therefore, appears in the Civil Code of Catalonia Code of Catalonia’. This law also introduced the accompanied by a certain mistrust, and given a first of the six books that were to set out the Ca- value which defines but also limits it, claiming a talan Civil Code. -

Antonio De Gimbernat

European Journal of Anatomy November, 2016 Vol. 20, Supplement 1 Honoring Don Antonio de Gimbernat Anatomist and Surgeon (1734-1816) Cambrils (Tarragona), 19 November 2016 Bicentenary of Gimbernat's death Guest Editor: Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Pedro Mestres Ventura PROLOGUE On June 20, 2015 I met in Cambrils with Drs. Sitges (University Pompeu Fabra / UAB), Navarro (Catalan Society of Surgery), Vinyes (Royal Academy of Medicine of Catalonia), Sañudo (Complutense University of Madrid) to propose an act in memory of Don Antonio de Gimbernat to be celebrated in 2016, the year which marks the 200 th anniversary of his death. The idea won unanimous support and it was decided that an academic conference with lectures on his life and work should be held on November 19 in Cambrils. During this meeting we also discussed the publication of these lectures in a journal of international standing. Thanks to the generous offer of Dr. Sañudo, Editor-in-Chief of the European Journal of Anatomy, a platform for this publication was quickly found. This book contains not only papers, which will be presented during the conference on November 19, but also others which were independently submitted and were accepted because of their thematic interest and quality. Despite the many years which have passed, Gimbernat remains an historic figure, remembered and admired not only by anatomists, surgeons and physicians. From the beginning Gimbernat understood anatomy as an applied science; as a basic discipline for the practice and advancement of surgery. After a long stay in several European countries, Gimbernat returned to Spain where he initiated a process of renewal and Europeanization of both Spanish surgery and medicine.